The Most Incredible Parts of Carnegie Hall Are Offstage

(Photo: Victoria Lipov/Shutterstock.com)

In the early 1980s, a woman attending a performance at Carnegie Hall dropped her music score on the floor, where it promptly fell into an air vent. This was somewhat problematic as she had borrowed it from the New York Public Library. She enlisted a backstage artist attendant, Gino Francesconi, to see if he could help retrieve the score.

At that time, between every tenth seat, an air vent led to big gap between the balcony and the dress circle. The usher knew of a trap door that led into this space, and a ladder that went down into it. Climbing down to look for the missing score, Francesconi found something quite remarkable. For many years, after a concert, instead of putting programs in the trash and dragging the trash down five flights of stairs, the porters dump the programs down the air vents. Francesconi came across what he describes as “this strata of programs”, going back decades, “filthy as the coal mines in Appalachia.” Gathering up the old programs it became “pretty much collection one” of the archives of one of the world’s most prestigious concert venues.

The Rose Museum inside Carnegie Hall displays the best of the archives (Photo: Luke Spencer)

Originally Francesconi had dreamt of being a conductor but today, along with his dedicated team, he oversees around 300,000 artifacts, some of which are housed in the venue’s Rose Museum. By creating a collection that tells the story of one of the most famous performance halls in the world, Francesconi has made himself the keeper of Carnegie Hall’s secrets.

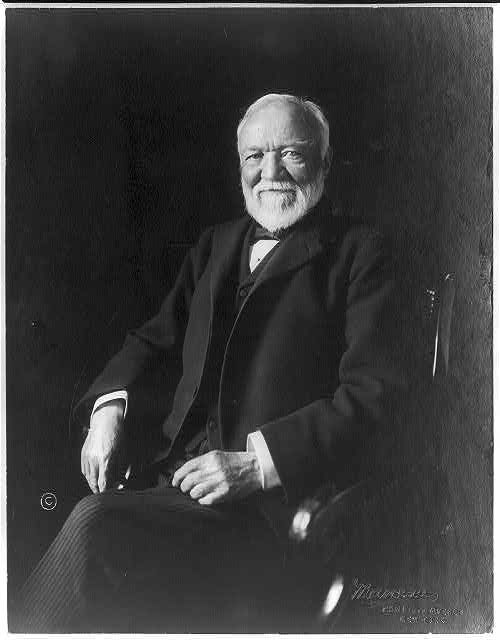

Andrew Carnegie was born in Dunfermline, Scotland in 1835. The son of handloom weaver, the Carnegies lived in relative poverty, occupying a cottage with one main room. Borrowing the money to emigrate, the family moved to Allegheny, Pennsylvania, where Andrew found work first in a cotton factory, then as telegram messenger boy for Western Union. By the age of 22, the Pennsylvania Railroad employed him.

It was during this time that he became interested in steel, the source of his future fortune. Thanks to innovations in steel production, the Carnegie Brothers Steel Company was the largest in the world by 1889, and was capable of turning out over 2,000 tons of steel a day. As cities and railways expanded all over America, it was invariably built with Carnegie Brothers Steel, making Andrew Carnegie one of the wealthiest men in the world.

Andrew Carnegie, c 1913 (Photo: Library of Congress)

In 1901, he sold his company to J.P. Morgan, creating US Steel, for $480 million (around $13 billion in today’s money). Morgan paid Carnegie in gold bond that were stored in the Hudson Trust Company building in Hoboken. The riches were so vast a special vault was built to house them. (The building on the corner of Hudson and Newark Streets is still there, but is today a branch of Starbucks). After this deal, Andrew Carnegie, 66, did something quite remarkable with his riches: He started getting rid of it.

Carnegie eventually gave away around 90 percent of his vast fortune.

Among his causes, the New York Public Library was given $5 million; over 2,800 other libraries were opened thanks to his philanthropy. He founded the Carnegie-Mellon University in 1904, donated the money for an estimated 7,000 church organs, started countless university trust funds and the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. He also decided to build a majestic concert hall for the city of New York.

A detail from the exterior of Carnegie Hall. It was the only concert hall William Burnet Tuthill ever designed. (Photo: Luke Spencer)

Carnegie Hall occupies the city block of 7th Avenue between 56th and 57th streets. Designed by architect William Burnet Tuthill in a beautiful Italian Renaissance style of deep red brick, it featured three main performance halls with impeccable acoustics. Two towers were added in the mid-1890s that was originally used as artists apartments.

Starting with Tchaikovsky in 1891, Carnegie Hall has hosted virtually every important artist, composer and performer since then. Those who have graced its stages include Ella Fitzgerald, the Beatles, Judy Garland, Leonard Bernstein. For many years it was home to the New York Philharmonic. Until 1986 however, there had been little effort to preserve Carnegie Hall’s history. After discovering the hidden hoard of concert programs in the air vents, Francesconi and his team set about collecting photographs, autographed posters, musical manuscripts, and videos” all of which “tell the history of the building and the events that made it famous.”

The Isaac Stern Auditorium / Ronald O. Perelman Stage (Photo: Ching/Flickr)

The Isaac Stern Auditorium / Ronald O. Perelman Stage (Photo: Ching/Flickr)

Today the neighborhood surrounding Carnegie Hall is one of Manhattan’s most exclusive. But in the 1890s, New York City’s midtown was centered around 14th to 20th streets—Carnegie Hall sat between suburbs and farmland. (At its founding, city plans for West 57th Street show 112 empty lots between Broadway and Park Avenue near Carnegie Hall. ) Its remoteness, though, added to the privilege and kudos of playing there. As one critic put it, “what a difference forty blocks makes. If you were good enough, they went the extra mile to come see you.”. Carnegie Hall spurred the way for uptown development, as companies such as Steinway and Tiffany’s all moved uptown.

Five years after that initial survey, almost all 112 of the empty lots on West 57th were filled.

While the good name of Carnegie Hall gradually grew, word of something hidden within it spread: One of Manhattan’s most exclusive secret bars, Club Richman. Francesconi showed me the original method of entry, a complex door locking system that required two keys to enter. The doorman had one key, a club member would have the other. Similar to the ignition system of Cold War-era Soviet missiles, both keys had to be slotted in and turned simultaneously to allow entry. Club Richman was so secret that upon Carnegie’s death, when the Hall was willed to his wife Louise Whitfield, she had no idea that the illicit bar even existed. Appalled, she filed a lawsuit to close it down, but it prospered throughout Prohibition as a speakeasy.

Francesconi told me of a certain dancer who once shimmied across the stage of Club Richman called Lucille LeSueur. She would become known later as the actress Joan Crawford. Today, unfortunately, the former speakeasy is home to the Hall’s giant air conditioning units.

Carnegie Hall is full of such similar secrets. Walking around behind the scenes, the Hall is pleasingly filled with the bustle of preparation for the next event. Musicians and ushers in plush red jackets throng the passageways backstage, to the sounds of clarinets and trombones warming up.

Deep under Carnegie Hall, the original bedrock of Manhattan. (Photo: Luke Spencer)

As Francesconi led me through a maze of backstage passageways he explained that “it is all part of show business, everything is hidden away and part of the magic.” Walking down a luxuriously carpeted corridor lined with polished wood wall panels, where security guards are relaxing before that evening’s performance, the archivist stopped at one panel, identical to all the others, except it opened. Behind it, through a door, we entered a tunnel. “We’re actually below the sidewalk now”, he explained, obviously excited, “This is the 7th Avenue passageway.” Going further down underground, the original rock walls are still visible; the hard stone that was the foundation of Manhattan. As we walked past giant generators, Francesconi explained that the Hall electricity generators (dynamos) were so powerful that an arrangement was made with the local utility company to purchase power provided by Carnegie Hall on days when there were no events in the building’s three theaters.

This tunnel is directly below the 7th Avenue sidewalk (Photo: Luke Spencer)

Going through another door, we began to climb an ornate cast iron stairway, far out of concertgoers’ sight. Above the hall used to be apartments, which have now been turned into rehearsal spaces and recreation rooms for the performers. Once Marlon Brando lived here in a studio. Besieged with female admirers, he would often hide in the apartment of a girl on his floor. Francesconi showed me a note, attached to a dozen roses, he had given to her:

“In appreciation for courageous perseverance displayed in Hall Battling and neighborliness above and beyond the call of duty.........Not so Private Citizen, Marlon Brando.”

A further small doorway led to a narrow gantry in a room with a ceiling of low-hanging red brick archways. Climbing along the gantry, past beams, rods and wires we stopped and crouched halfway along. “Look down there,” said Francesconi in hushed tones. In a gap between the theatrical lights, I could see we were directly over the stage, high up in the rafters. “Isn’t this cool?” he asked as we looked down onto the immaculately polished stage below. Holding onto a wooden railing, Francesconi explained that it was original to 1891.

It is on one of these warren- like floors that the archives can be found. Francesconi and his team have been actively collecting and adding to the archive for decades now. Kathleen Sabogal (Assistant Director), Rob Hudson (Associate Archivist) and Shira Peltzman (Part Time Digital Project Manager) curate items that come from private donations, eBay hunting, and old- fashioned detective work.

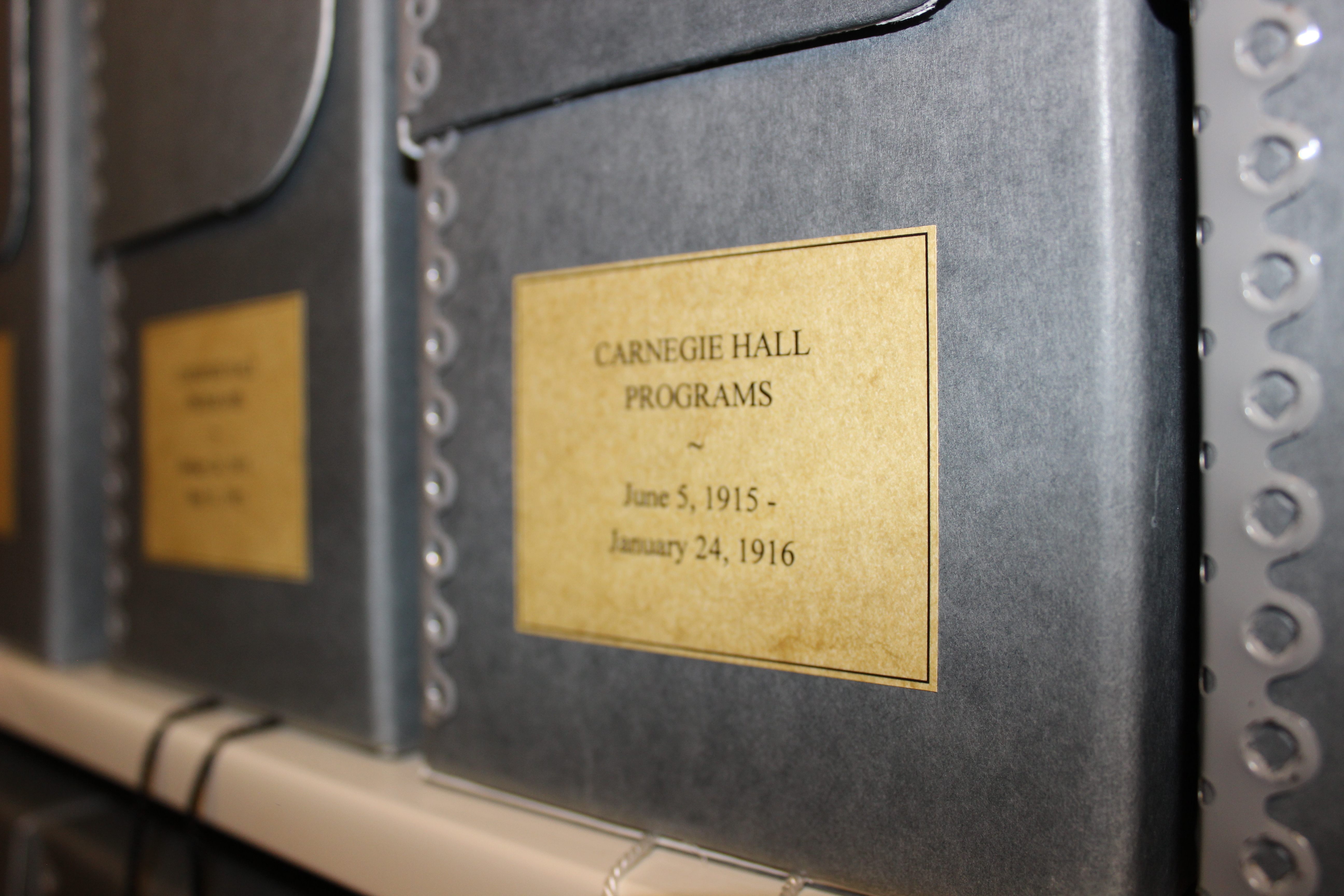

The Carnegie Hall archives now contains around 300,000 artifacts (Photo: Luke Spencer)

One shelf has rows of boxes marked “batons.” Inside sits the concert sticks used at Carnegie Hall by the world’s greatest conductors, among them Leonard Bernstein, Zubin Mehta and Arturo Toscanini. Another shelf is marked “programs,” going all the way back to the first night with Tchaikovsky.

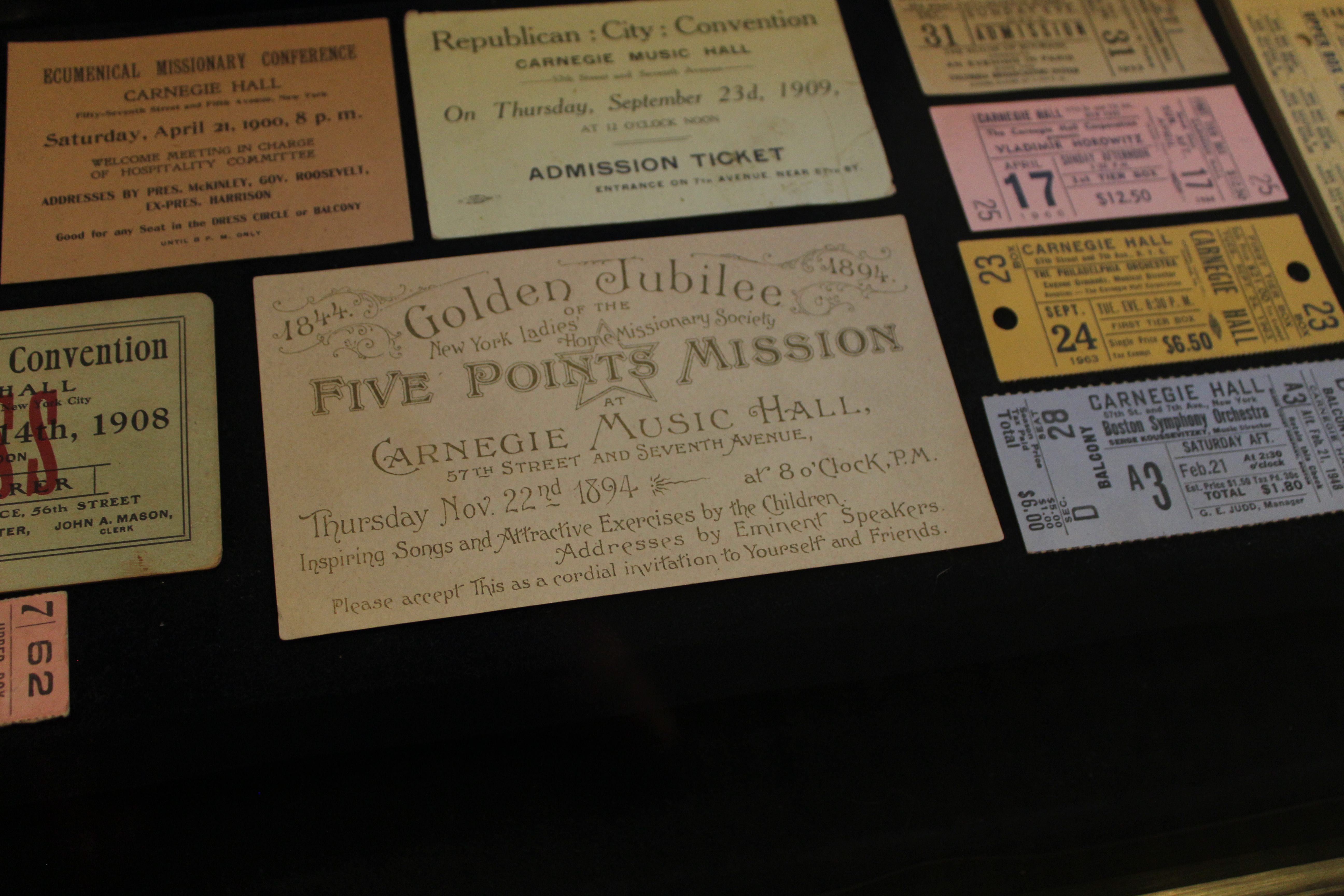

From Gershwin to the Five Points Mission, all were welcome at Carnegie’s Music Hall (Photo: Luke Spencer)

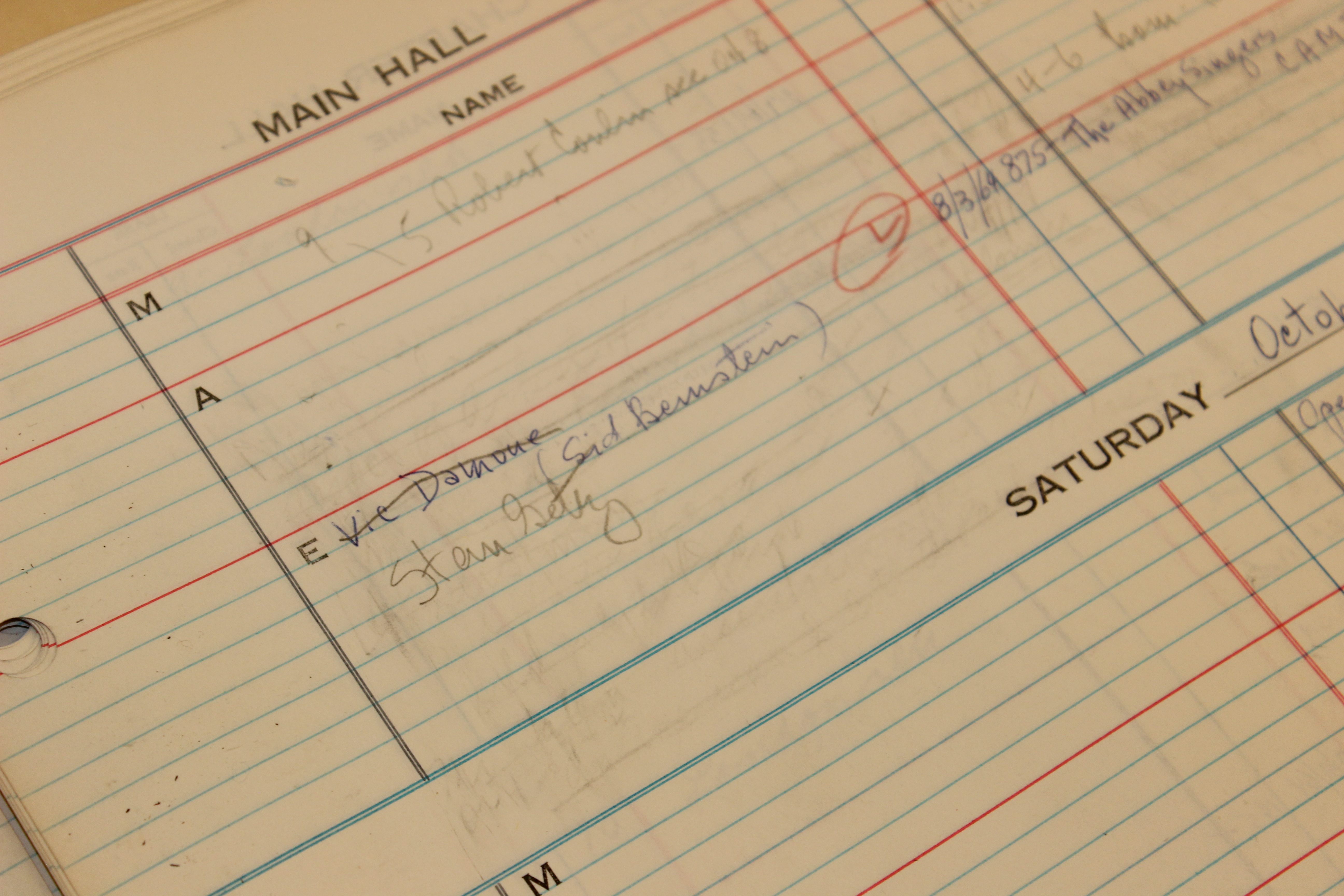

“This is neat,” said Francesconi, opening an oversized box filled with giant ledger pages. “These are pages from the original booking ledger. What’s really cool about this is, if you wanted to book the hall, you’d call the booking manager, for many years Iona (Didi) Satescu followed by the recently retired Gilda Weissberger.” She would see if the required dates were available and take down the details, never erasing anything, only crossing out canceled performers. Leafing through the ledgers is to look through the day-to-day history of Carnegie Hall. The same care was given to Stan Getz (Main Hall, 8/3/64, $875) as to the Macy’s Spring Bridal Fashion Show (Main Hall 12/2/63, also $875). On January 22nd, 1964, I could see that Weissburger had booked in “The Beetles (sic) presented by Walter Hyman” for two shows in the Main Hall for February 12th, for $1,750.

The king of Bossa Nova comes to New York, as noted in the original booking ledgers (Photo: Luke Spencer)

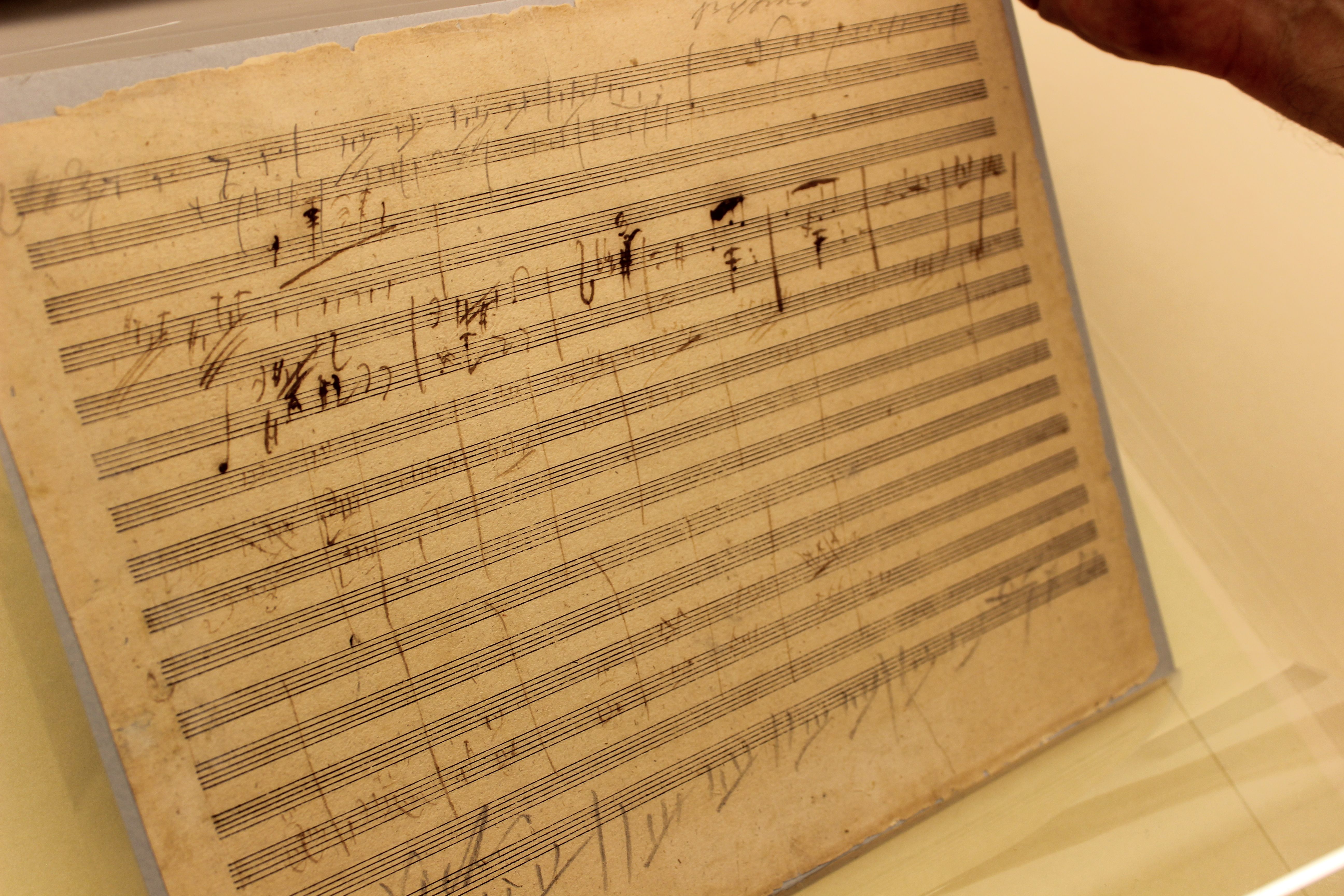

What are the most valuable single item in the archive? According to Francesconi, it’s a page from one of Beethoven’s sketch books, part of the score for the Wellington Symphony. It came to Carnegie Hall by a donation form doctor who had been treating a one-time executive director of the hall. Next to it was a meticulously neat excerpt of a score, part of “A New World A Comin’,’ written out by Duke Ellington in his own hand.

Part of the score for ‘Wellington’s Victory’ hand written by Beethoven himself (Photo: Luke Spencer)

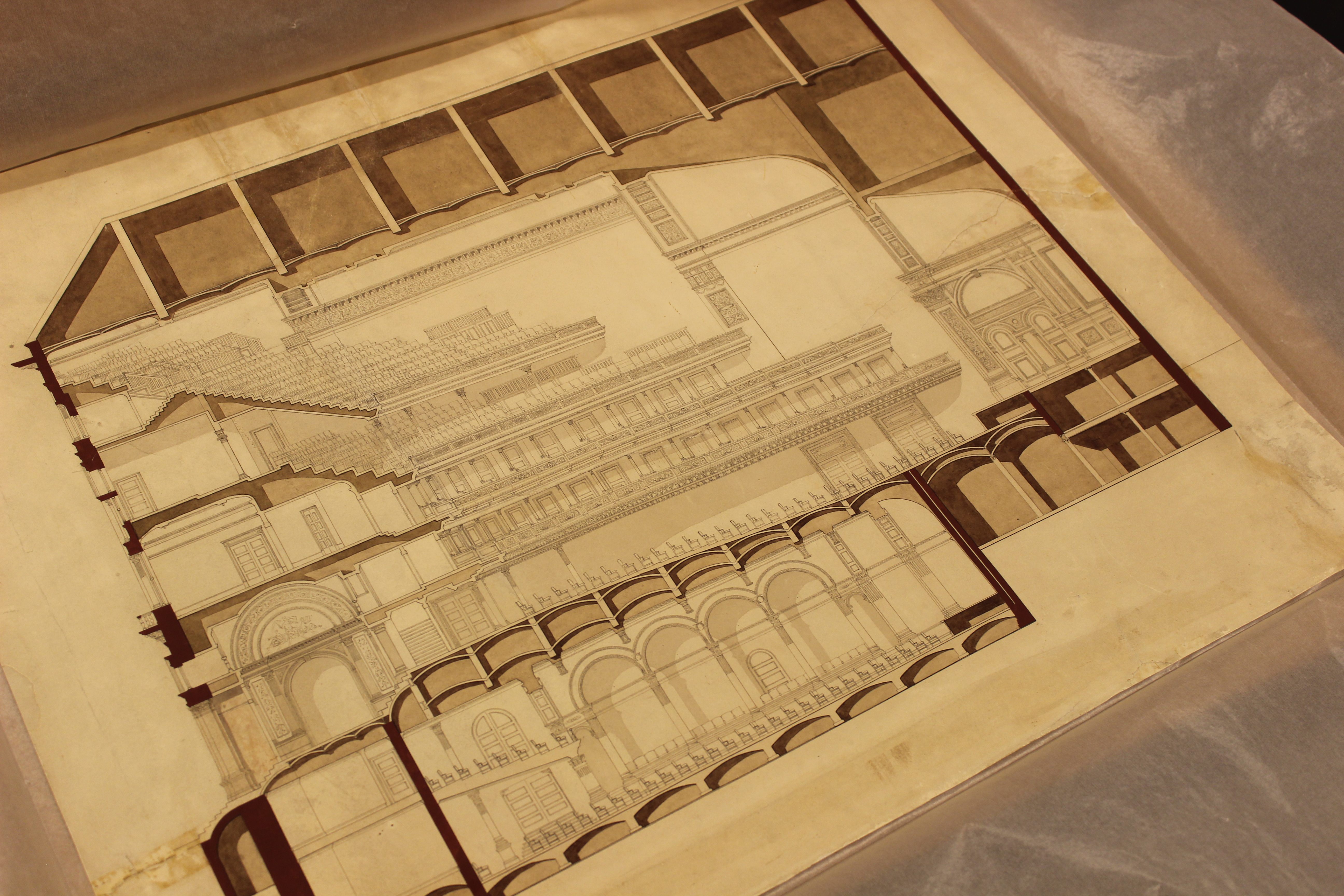

The original plans for Carnegie Hall, showing the rafters and tunnels, now restored and preserved in the archive. (Photo: Luke Spencer)

All of this history came very close to being lost. By the 1950s Carnegie Hall was in dire straits. New York realtor Robert Simon had purchased the hall from Louise Whitfield Carnegie six years after the magnate’s death. In 1955, with the anticipation of the new Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts, his son Robert Simon Jr put Carnegie Hall on the market. The rumored plan was to tear it down and build apartments.

A valiant effort by the Committee to Save Carnegie Hall, led by virtuoso violinist Isaac Stern saved the Hall and it was bought by New York City, with the day-to-day running of the Hall taken over by the nonprofit Carnegie Hall Corporation who also led extensive renovations of the historic hall.

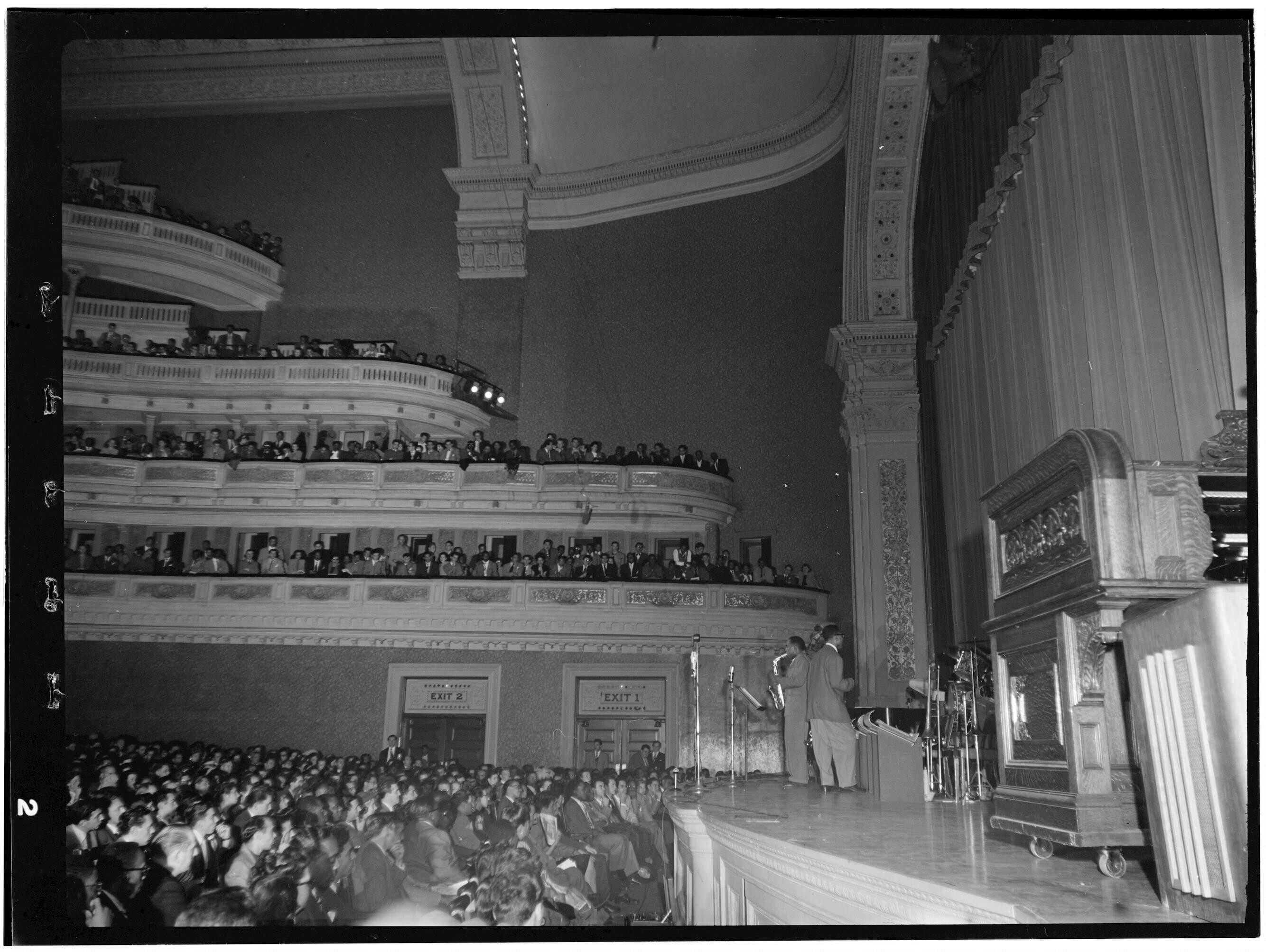

A photograph by William P. Gottlieb’s of Dizzy Gillespie and Charlie Parker at Carnegie Hall, c. October 1947 (Photo: Library of Congress)

Today it remains one of the most prestigious and world famous venues, and has hosted more than 50,000 events.. Inside the venue, the Rose Museum exists to rotate in pieces of the collection, with an emphasis on the star-studded appearances through its past. The archives is an ongoing work of collecting, curating, and now digitizing the vast collection, making it publicly available. Take for example, Ella Fitzgerald; the plan is for the online archive to show all her recordings, booking pages, autographs, correspondence and programs, “I want them to see everything,” said Francesconi.

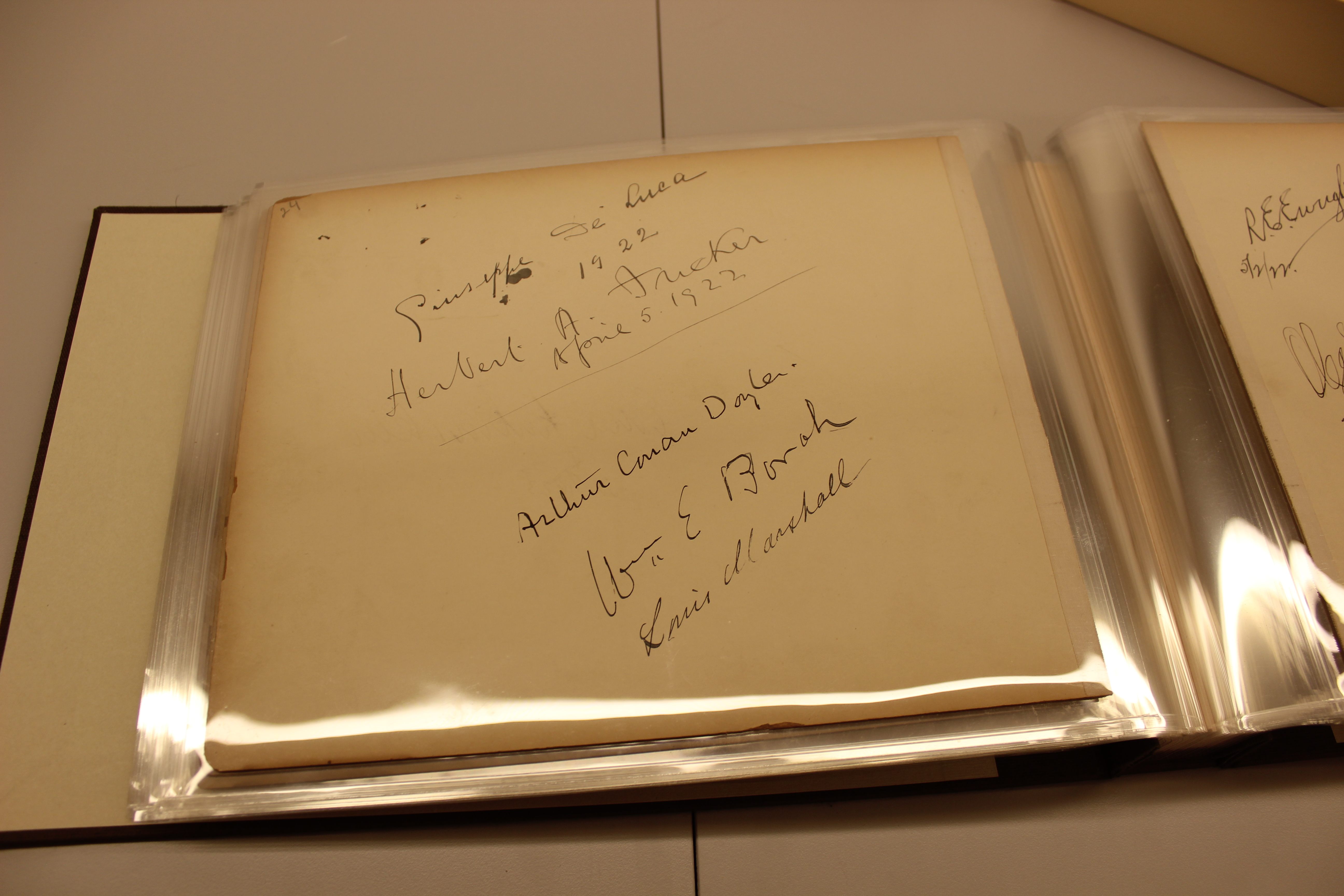

Francesconi’s favorite item is neither the most commercially valuable nor the most famous. When I asked him that question, he opened a box to show a small autograph book. It had been kept backstage by Louis Salter, the former house manager of Carnegie Hall. He had started working there in 1891 as a lighting engineer in the rafters. “He work his way down,” joked Francesconi, starting the book in 1916 and not letting any performer leave until they’d autographed it. Looking through the delicate pages is a window into 20th century history, the great names of the past of who trod the stages of Carnegie Hall. Starting with Paderewski, whose sold-out piano concerts put the hall on the map, other names include Leo Ornstein. Herbert Hoover, FDR, Richard Strauss and Rachmaninov. Arthur Conan Doyle is there, having come to Carnegie Hall to speak about spiritualism following the death of both his sons in World War I.

Louis Salter’s autograph book : 266 legendary names it took a decade to track down (Photo: Luke Spencer)

By the time Francesconi had heard about the book, it had already left the hall, going to the Salter family after Louis died. A nephew in Flushing, Queens, by the name of Green was the last person known to have it. In those days before the Internet, and armed only with a phonebook, Francesconi started to track the priceless book down. “Do you know how many ‘Greens’ there are in Queens? I called them all,” he said. The trail for Louis Salter’s autograph book took ten years, and led Francesconi to Florida, California and Washington State. One day he got a telephone call: “Gino, does the name Louis Salter mean anything to you?”

Today the book lives in the hall, perfectly preserved, digitized and able to be explored by all. It speaks to the wide array of great names of those who came to perform at this exquisite concert hall, and to the tireless efforts of one man who saved it. Wrapping the book back up in its protective acid-free box, Francesconi explained, “It’s my Maltese Falcon.”

Billie Holiday at Carnegie Hall, c. 1946 (William P Gottlieb/Public Domain/WikiCommons)

Update, 6/11: The story contained a few errors that we fixed: the woman in the first paragraph was attending a performance at Carnegie Hall, not rehearsing for it; two towers were built in the mid-1890s, not one; the critic who wrote about Carnegie Hall was not from the New York Times; it’s the New York Philharmonic, not the New York Philharmonic Orchestra; and George Gershwin was not one of the names in Salter’s ledger. We regret the mistakes!

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook