The Handy Playing Cards That Taught 17th-Century Cooks to Carve Meat Like a Pro

The decks suggested proper technique, and were a path to class mobility.

Push back your chair and sharpen your knife. It’s dinnertime in 17th-century England, and you happen to be flush enough to get your hands on a plump, juicy turkey. You’ve gathered friends and family, and now it is time to carve the bird. You want to make sure there are enough pieces to go around, but also impress your guests with your dexterity—or, at the very least, not splatter them with grease and bits of skin.

Today, you might watch an instructional video, but then you may have turned to a deck of playing cards.

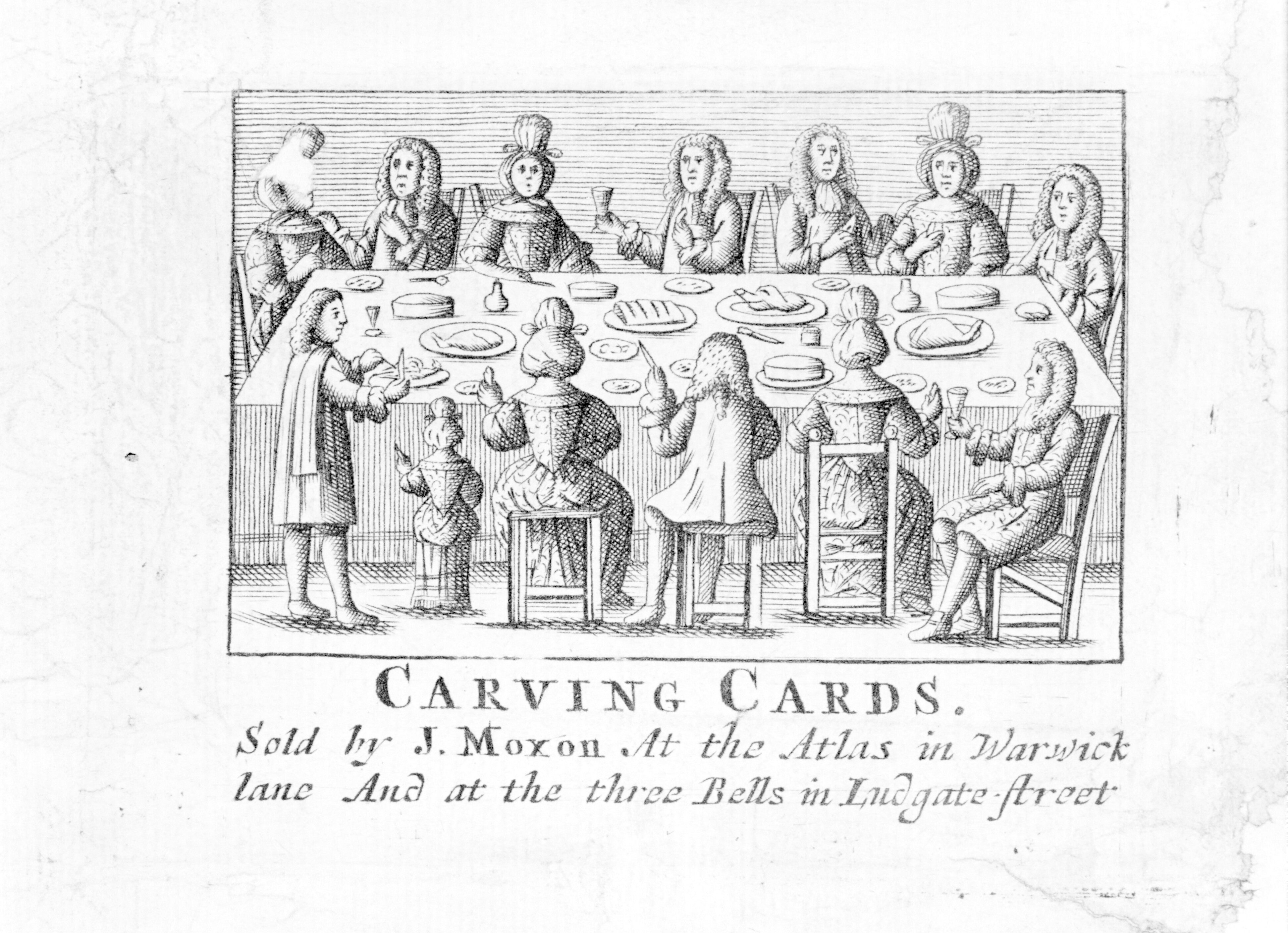

“The genteel house-keeper’s passtime, or the mode of carving at the table represented by a pack of playing cards” was a deck and accompanying booklet first issued by London printer Joseph Moxon in 1677. It had roughly the same dimensions as any other deck, but these cards had a purpose beyond games: to teach people how to carve, hack, and disarticulate any (formerly) living thing they planned to serve. The booklet argued that proper carving can curb waste and buoy appetites. “Methodical cutting,” the anonymous author wrote in a 1693 edition, would protect “weak stomachs” from heaving at the sight of “disorderly mangling a Joynt or Dish of good meat.”

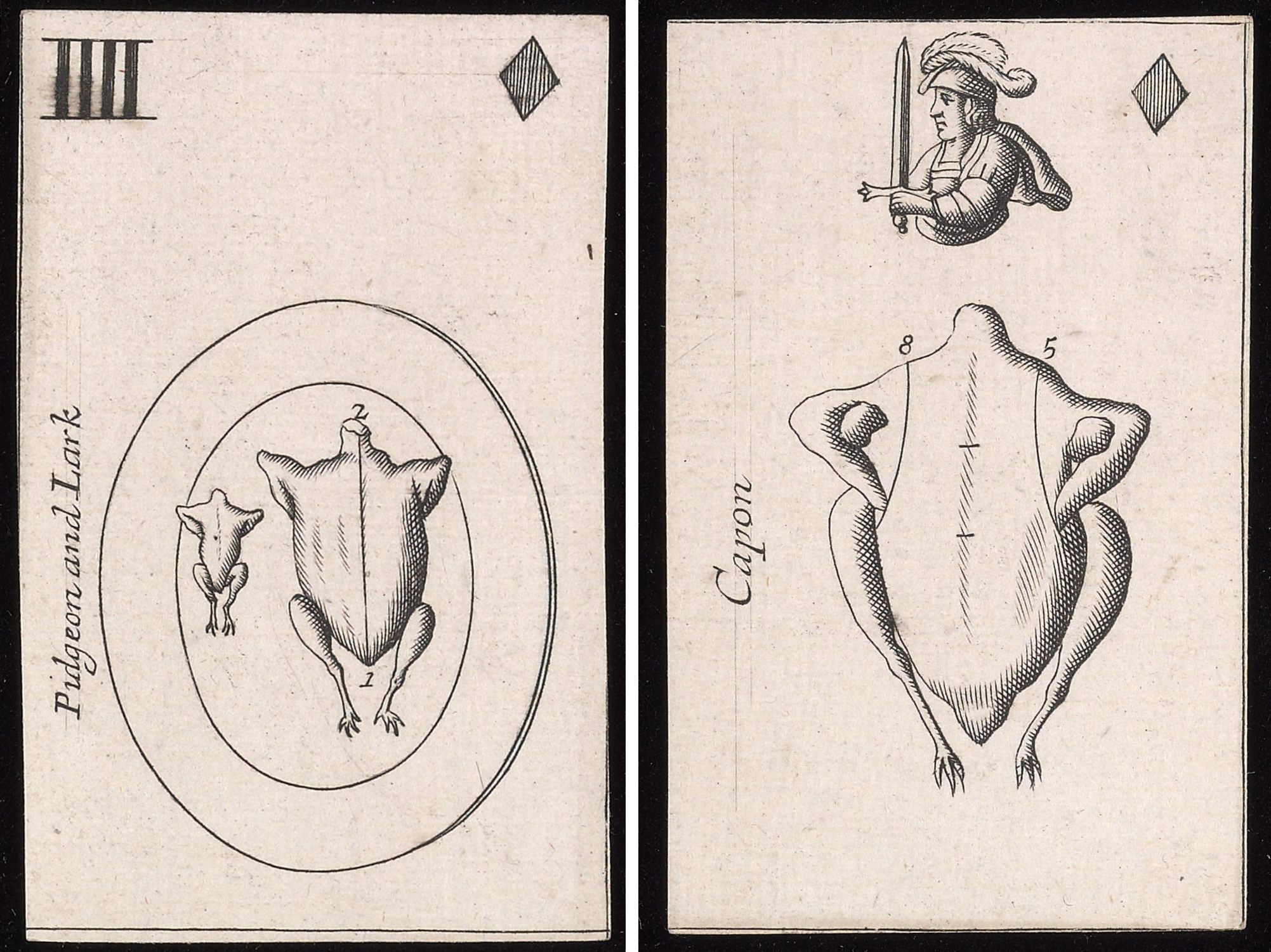

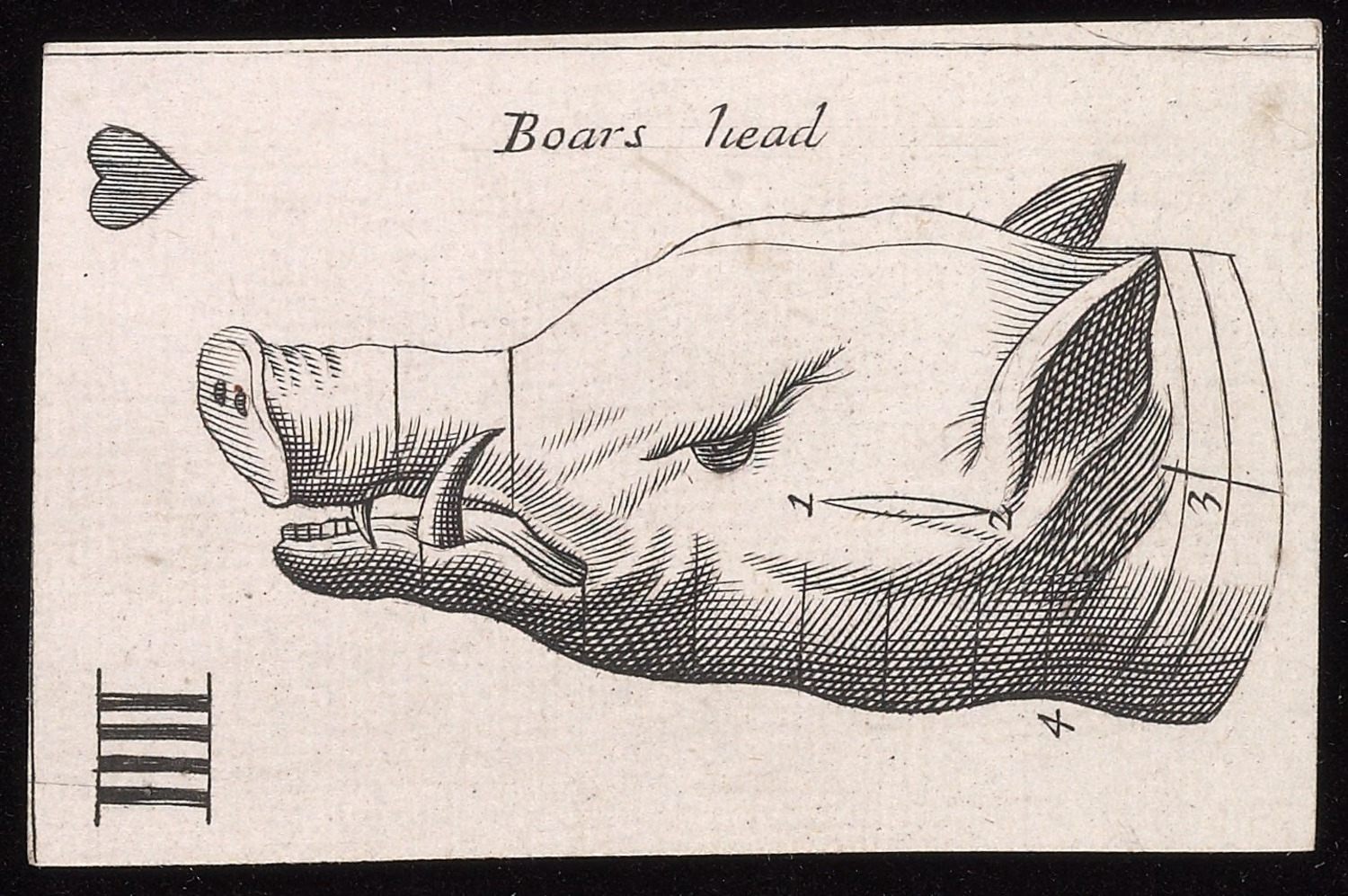

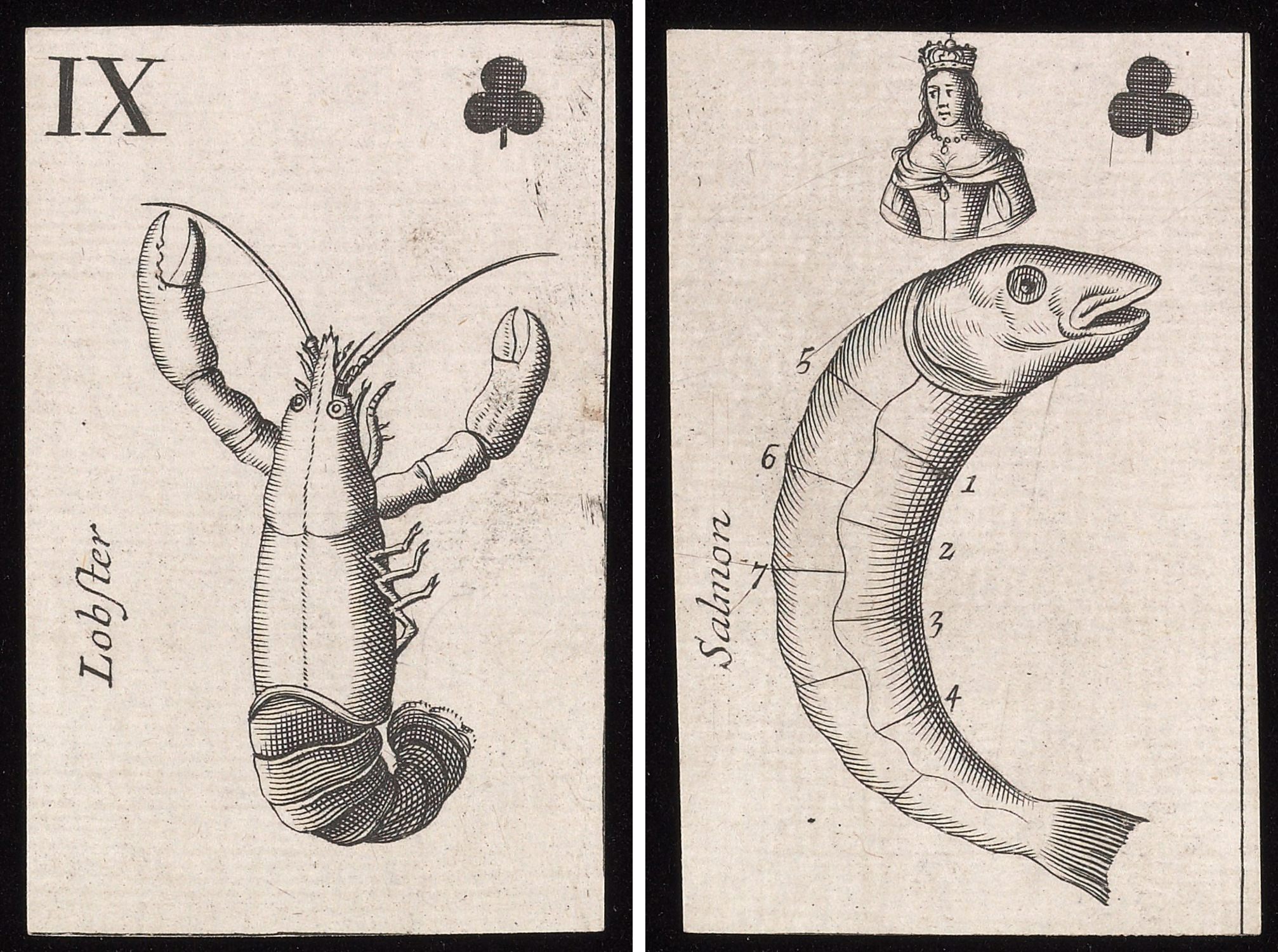

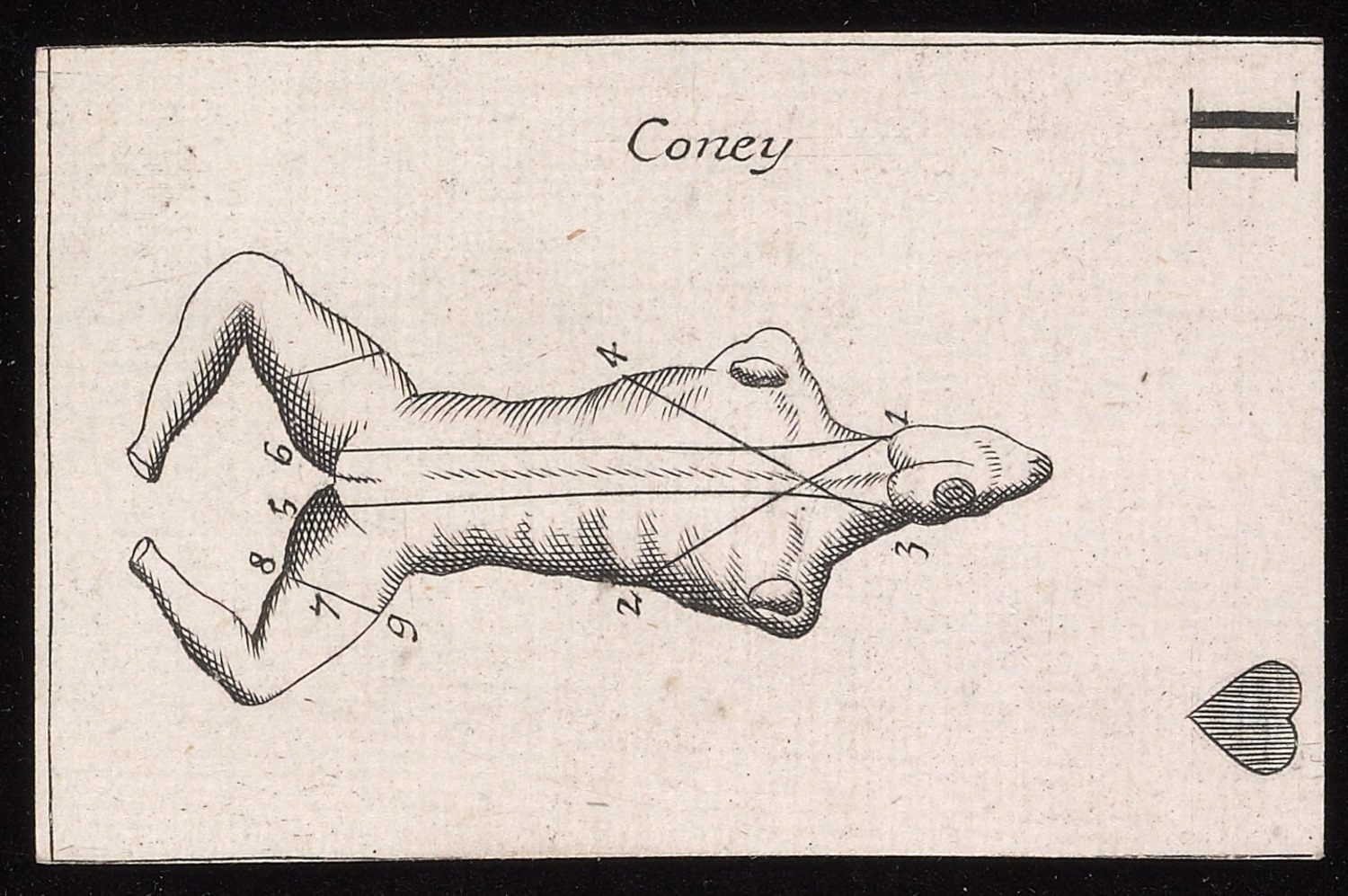

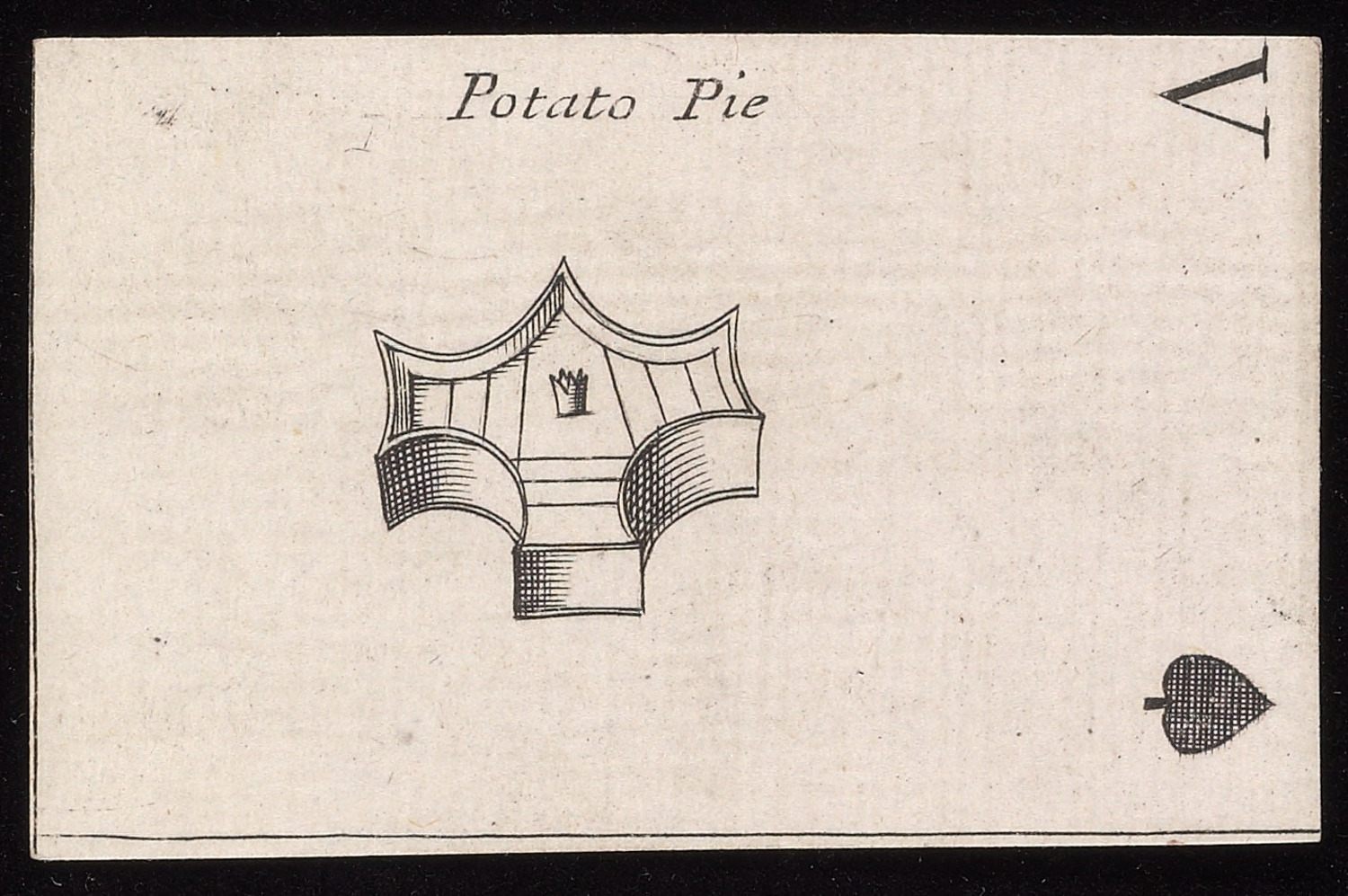

Each suit corresponds to a different type of meat. Feeling fishy? Deal the clubs to learn to how to gut a salmon or dismantle a lobster. The diamonds were for fowl, from duck to pheasant to pigeon (which shouldn’t be carved, but simply “cut through the middle from the rump to the neck”). The hearts featured “flesh of beats,” from the “Sir Loyn of Beef” to a haunch of venison—“begun to be cut near the buttock”—and a boars’ head, which “comes to the Table with its Snout standing upward and a sprig of Rosemary tuck[ed] in it.” Coney, or rabbit, was “most times brought to the Table with the Head off” and placed alongside the body. Instructions for carving “baked meats,” such as pies and pasties, were on the spades.

The cards were schematics, but quite vague. The booklet was a useful addition, as it broke down the drawings step by step, describing the process of cleaving wings and thighs and offering tips for adding flourishes to the finished dish. Capon ought to be ringed with thin slices of oranges and lemons around the serving platter, while a goose called for sugary, buttery apples, or maybe some gooseberries or grapes. Lobster meat was best served “mingled or tempered with grated Bread and Vinegar,” and garnished with fennel or a dash of green herbs. The booklet also outlined how the carver should behave and dress. Neatly attired knife-wielders ought to avoid manhandling the meat with their fingers—and if poking couldn’t be avoided, only the thumb or forefinger would do.

“I would say these were not intended for game play,” according to Timothy Young, the playing-card librarian and curator of modern books and manuscripts at the Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library at Yale University. They weren’t especially cheap to make—cards called for pasting many leaves of paper together so they would hold up to repeat use—but they were particularly useful for conveying information. Educational decks were fairly common at the time, Young says, covering everything from constellations to the countries of the world and historic kings and queens. Cards were portable and easy to pass around, which made them popular among tutors with multiple pupils. They had obvious appeal for the kitchen or dining room. A card tacked to the wall or leaned against a tray on the table would have been a relief for a harried chef wrist-deep in a roast, who might otherwise leave a trail of unsavory smudges across book pages.

The cards fit in with a trove of domestic manuals and instructional books that had come on the market in England in the 16th century, says Jennifer Park, an assistant professor of English at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro, who works on Renaissance recipes, games, and ephemera. “The idea was that what was [once] in the domain of professionals, you can now do in your household, in your private space,” Park says. “It’s not secret knowledge that’s locked away.” Though this manual and deck were penned by an anonymous writer, the text promises readers that the tips were “set forth by several of the best Masters in the Faculty of Carving, and Published for publick life.”

Beyond teaching useful skills, the cards also helped home chefs reach toward higher status. Young sees the deck as an early example of the middle-class thirst for upward mobility. Moxon’s cards were “designed to aid families who had become wealthy enough to serve meat to guests, but were not yet wealthy enough to hire professional carvers,” writes Edward A. Malone, a professor of technical communication at Missouri University of Science and Technology, in a 2008 paper about playing cards’ history as vehicles for technical know-how and scientific information. The cards would have been indispensable kitchen tools for “people who want to have this mannered, proper way to cook and present food, but don’t depend on people doing it for them,” Young says. The truly wealthy had no need to know how to wield a knife with confidence or elegance, Young adds—their kitchen staff had those skills, and they had little inclination to get their hands dirty. Moneyed diners would think, Young says, “‘I don’t know, I go to dinner and it’s just there.’”

It’s hard to know for sure how many decks were in circulation—Young says contemporary claims about print runs ought to be taken with a pinch of salt, because they were often inflated to drum up publicity—or exactly when they stopped showing up in English kitchens. (There’s no way to gauge when a shop would have worked through its stock.) Malone writes that they were available for roughly four decades, and “must have been popular at the price of 1 shilling per pack.” (The booklet, he adds, was a half-shilling more.) The Beinecke has some loose cards produced around 1680, plus a version from 1693 that had not been cut from the original printing. Wellesley College has a version from 1717, attributed to a different printer who likely acquired the rights—and maybe even the plates—to reprint Moxon’s designs. Judging by the scarcity of other records, the cards probably didn’t have a shelf life much beyond the early 18th century. After that, Young says, “we assume that they dropped out of circulation because we don’t have anything until much later facsimiles.” For the generations of carvers who followed their lead, though, the cards were much more than just an appetizing novelty.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook