The Wild Tale of the Cerutti Mastodon, a Fossil That Could Rewrite the Human Story

The Cerutti Mastodon, found near San Diego, shows signs of being butchered 130,000 years ago—but by who? Or what?

California’s highway State Route 54, skirting southeast of San Diego, doesn’t seem like it would be the catalyst for challenging some of the longest-held ideas about human evolution and our spread across the planet. And yet, in 1992, along SR 54’s ribbons of asphalt and exit ramps to malls, taco joints, and subdivisions, road-widening construction unearthed a fossil that could rewrite the human story—if scientists ever stop arguing about it.

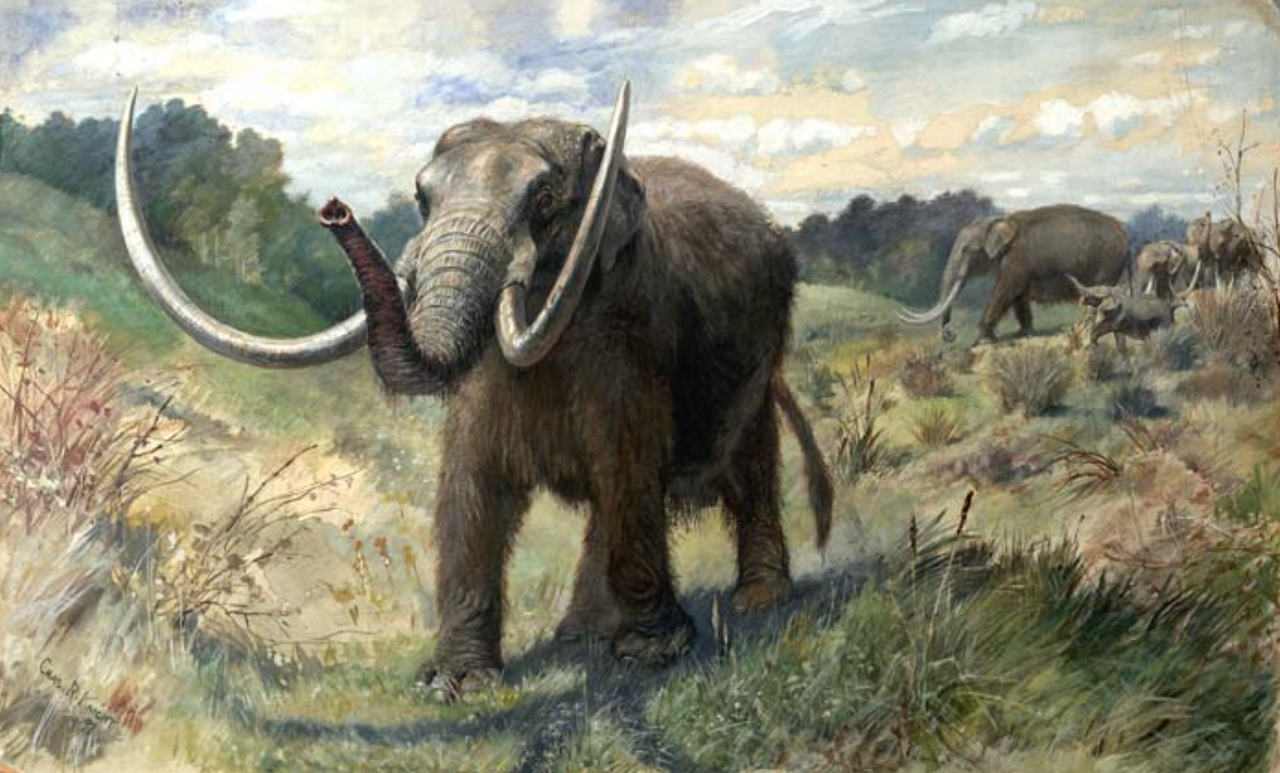

Here, 130,000 years ago beside the future site of SR 54, a young mastodon perished. There’s nothing uncommon about that—these heavily-built, distant relatives of modern elephants were found throughout much of North America at the time. Paleontologists don’t know how the mastodon died, but there is evidence preserved in its bones, and in rocks found nearby, that the animal’s carcass may have been butchered by humans. There’s just one problem with this scenario. Most scientists agree: Homo sapiens left our ancestral homeland of Africa less than 100,000 years ago, and arrived in the Americas only in the last 15,000–25,000 years, as the last ice age ended and travel from Asia and the land bridge known as Beringia, into Alaska and Canada, became possible.

So who—or what—made a meal out of that mastodon?

The fossil is now known as the Cerutti Mastodon, after the late paleontologist Richard Cerutti, who recognized the significance of the bones as they were uncovered during the highway expansion project. Greater San Diego was growing rapidly at the time, and so was its infrastructure. Previous highway projects had turned up a wealth of fossils, from ancient walruses to dinosaurs, and Cerutti worked on behalf of the San Diego Natural History Museum as a site monitor, on the lookout for more discoveries. But he wasn’t expecting this.

Cerutti was initially excited because he thought the fossil belonged to a mammoth. However, further excavation over several months revealed the distinctive teeth of its close relative, the mastodon—and turned up strange things neither Cerutti nor his colleagues could explain.

The heavy, massive limb bones of a mastodon are not easy to break, and specific fracture patterns on the Cerutti specimen were not consistent with natural processes, such as being tumbled in river rapids. There was also the curious arrangement of the bones. Two broken femurs appeared to be placed side by side, and one of the animal’s tusks was almost vertical, as if stuck upright in the sediment like a flagpole.

There were few rocks found in the silty sediment around the bones. However, some of the isolated rocks the team did uncover appeared to have been intentionally shaped and then used to smash something.

Cerutti and his colleagues believed that the site had all the signs of being used by humans to process an animal carcass—but that it was simply too old to fit into any recognized model for the arrival of humans in the Americas.

The timelines for when Homo sapiens left Africa, and when they arrived in the Americas, are two of the most contentious issues for scientists piecing together the human story. To challenge either—never mind both at once—without conclusive evidence would have ended the team’s careers. Invitations to other archaeologists to examine the material were politely declined, likely for the same reason. So for more than a decade, the bones and rocks sat unremarked in San Diego’s Natural History Museum.

In the late 2000s, Steven Holen, research director for the Center for American Paleolithic Research, and Kathleen Holen, his wife and fellow archaeologist, decided to take a look. They reached the same shocking conclusion as Cerutti and his colleagues. The Holens have long advocated for an early arrival of our species to the Americas, attracting critics along the way, and were undaunted by the prospect of proposing such a wild revision to the established timeline. But first, they had to make their case.

Cerutti, the Holens, and a growing list of experts from multiple disciplines—from paleontology to geology to uranium-thorium dating—spent nearly a decade studying every aspect of the find. They considered and eliminated a host of other possible explanations, including natural events, such as mudflows, and damage inflicted on the fossilized bones during the ’90s construction project. Steven Holen even got a little grisly in his field work: He used stone tools to break the bones of recently deceased elephants to confirm that the resulting fracture patterns were consistent with those of the Cerutti Mastodon.

The team’s conclusion, published in 2017 in Nature: The mastodon’s bones were processed shortly after its death, dated to about 130,000 years ago.

Acknowledging that anatomically modern humans—that’s you and me—had not left Africa at this point, the authors refer to the butchers only as “an unidentified species of Homo.” In addition to H. sapiens in Africa, the fossil record shows that at least three other members of our genus were around: Denisovans in Central Asia, Neanderthals mostly in Europe, and the last members of H. erectus, an earlier branch on our family tree that once lived throughout much of Africa and Eurasia. (Archaeologists have recovered stone tools, believed to be made by H. floresiensis, our small-statured relative in Indonesia, from about this time—but fossils of the so-called “hobbit” are younger.) There is, however, no evidence that any of our evolutionary kin ever got anywhere near the Western Hemisphere.

Criticism of the paper was fast and furious.

Most leading voices in the field dismissed it out of hand, some calling it “astonishingly bad” or “not credible,” and several citing the much-quoted line that “extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence.” A handful of archaeologists initially expressed at least a willingness to consider the team’s hypothesis: “We need to leave our minds open. I admire these colleagues for sticking their necks out,” Vanderbilt University’s Tom Dillehay told Scientific American. Years earlier, Dillehay himself had challenged the conventional timeline of humans arriving in the Americas around 13,000 years ago by proposing the controversial Monte Verde site in Chile was 20,000 years old. But as media attention and public interest in the discovery snowballed, even the open minds closed. An unrelated paper on the arrival of people to the Americas at the end of the Ice Age—coauthored by Dillehay—made a point of citing the Cerutti Mastodon conclusions as an example of an “implausible claim” and chided “some scholars and members of the general public” for accepting it.

Several experimental archaeologists declared Holen’s bone-smashing field work as poorly conceived and executed. The damage to the bones, critics argued, could have been caused by the animal being trampled by other mastodons shortly after its death, or scavenged by one of the period’s massive and powerful predators, such as the short-faced bear, which was even larger than today’s polar bear.

The mastodon-sized brouhaha died down almost as quickly as it began. Cerutti died in 2019 and, after several rebuttals to critics, the Holens turned their attention to other sites. In 2020, some of the coauthors of the divisive 2017 paper published new evidence that the rocks found near the bones were used to process the mastodon carcass, based on microscopic residues and wear patterns, but the findings did little to change opinions.

The Cerutti Mastodon might have become a footnote in the book of the human story, relegated to the chapter on fringe theories abandoned for lack of conclusive evidence. But something else has happened. The bombshell claim about the Cerutti Mastodon has quietly led to a broader and more inclusive discussion about humans arriving in the Americas.

Paulette Steeves, an Indigenous archaeologist from Canada, highlighted the Cerutti Mastodon site in her 2021 book, The Indigenous Paleolithic of the Western Hemisphere, and included it in her database of hundreds of sites that she believes prove humans have been living in the Americas for more than 100,000 years. Her work incorporates Indigenous and Western methodologies with the goal of stepping “outside the box of Western colonial bias,” according to the database introduction.

In 2023, archaeologist Ruth Gruhn, whose 60-plus years of research earned her the nickname “the First Lady of First Americans Studies” from her peers, authored a paper in the journal PaleoAmerica that urged a rethink of the current conventional timeline for the arrival of humans in the Americas. While she did not mention the Cerutti Mastodon site specifically, she argued that the growing number of archaeological sites predating the end of the last ice age indicates a human presence in the Americas much earlier than currently accepted.

The significance of the Cerutti Mastodon remains highly disputed, with few scientists embracing the 2017 paper. The long-dead mastodon’s ultimate legacy could be to remind us that the next tantalizing challenge to conventional ideas about our shared past may be just one highway construction project away.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook