Life in Pripyat Before, And the Morning After, the Chernobyl Disaster

When the scale of a tragedy dawned.

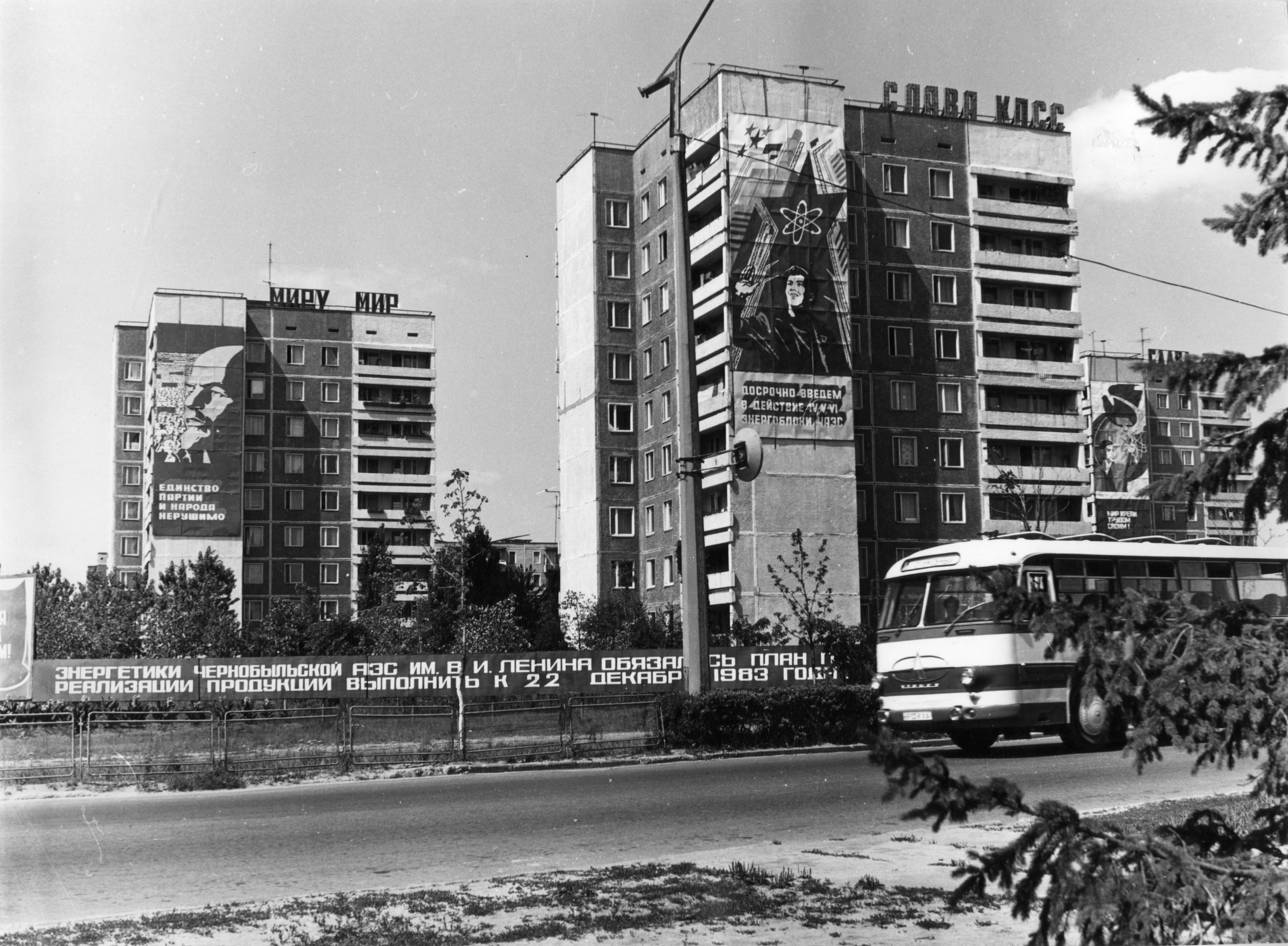

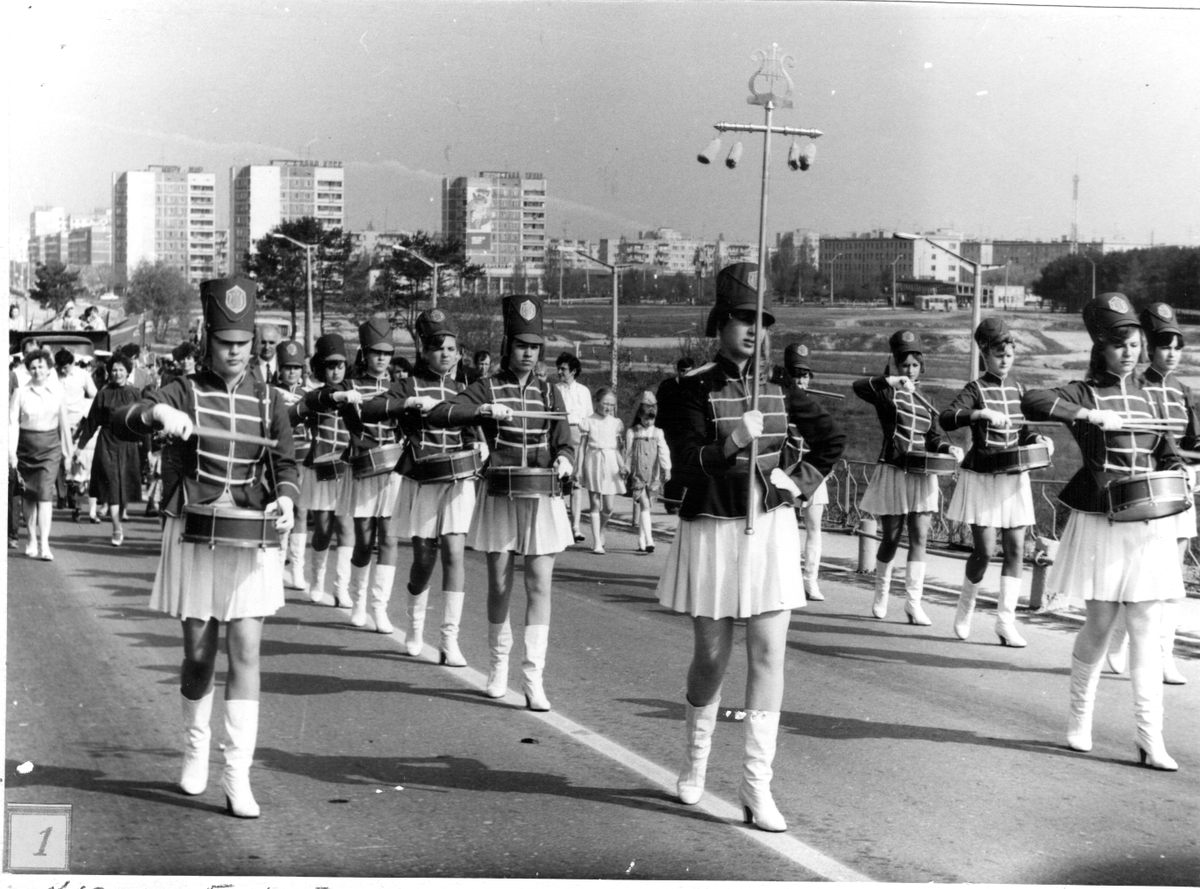

In the early hours of April 26, 1986, a nuclear accident took place during a safety test at the Chernobyl Atomic Energy Station near the city of Pripyat, in what was then the Soviet Republic of Ukraine. In this excerpt adapted from Adam Higginbotham’s new book, Midnight in Chernobyl—illustrated with photos of life in Pripyat before the accident—civic leaders and others begin to realize the gravity of the situation.

It was sometime after 3:00 a.m. when Alexander Esaulov was jangled awake by the telephone. Shit!, he thought as he fumbled for the receiver. Another weekend ruined.

With his wife and children off with the in-laws for a few weeks, he’d been looking forward to enjoying a few days to himself: perhaps squeezing in a little fishing. Having the two children at home—a five-year-old daughter and a son about to turn six months—there was always plenty of work to do, even without his job. And as the deputy chairman of the Pripyat city ispolkom—the equivalent of deputy mayor—Esaulov spent his days reeling from one administrative headache to another.

He had come to Pripyat from Kiev, where he had worked in the city’s municipal financial planning department. It was a nice step up for the 33-year-old accountant and his family: out of the rotting communal apartment with a queue for the bathroom every morning, into the clean air of the countryside, and a prestigious job with his own secretary and the use of a car—dilapidated but serviceable—for work. Still, Esaulov found his new responsibilities onerous. He had to manage Pripyat’s city budget, expenses, and income—but also served as the head of the planning commission and oversaw transportation, health care, communication, road and street cleaning, the employment bureau, and the distribution of building materials. There was always something going wrong, and the citizens of Pripyat were never hesitant to complain when it did.

On the phone was Maria Boyarchuk, the secretary from the ispolkom. She’d just been woken by a neighbor who had come from the nuclear power plant. There had been an accident: a fire, maybe an explosion.

By 3:50 a.m., Esaulov was at his desk in the ispolkom offices. The chairman—the city mayor—had left for the plant to find out what was going on. Esaulov telephoned the head of Pripyat’s civil defense, who sprang from his bed and raced over to the office. But neither of them had any idea what to do. The plant had its own civil defense staff, and the city had never been involved in any of its exercises. There had been accidents at the station before, but they had always been cleaned up with a minimum of fuss.

Now they phoned every number they had at the station, but no one would tell them anything. They considered driving there, but didn’t have a car. All they could do was sit and wait. Outside the window, the streetlamps threw pools of amber light across the square; the apartments along Kurchatov Street remained dark and silent.

But as dawn approached, Esaulov watched from behind his desk as a single ambulance raced down Lenina Prospekt from the direction of the plant. Its emergency lights flashed, but the siren remained silent. The driver took a sharp right at the Rainbow department store, tore along the southern side of the square, and then swung away in the direction of the hospital. A few moments later, a second ambulance followed, and it, too, disappeared around the corner.

The blue lights faded into the distance, and the city streets were still once more. But then another ambulance sped past. And another. Esaulov began to suspect that there might be something different about this accident, after all.

As dawn broke, word began to spread among those with friends and relatives on the midnight shift at the plant that there had been some kind of accident. But nobody could say exactly what.

At around 7:00 a.m., Andrei Glukhov, who worked in the reactor physics laboratory at the plant, was in his flat on Stroiteley Prospekt when the phone rang. It was a friend from the Instrumentation and Control Department. He, too, was at home and had heard that something had gone wrong at the station, but he didn’t know any details. As a member of the Nuclear Safety Department, Glukhov had the authority to make calls directly to the control rooms of every reactor at the plant. Would he mind making a few enquiries?

Glukhov hung up and phoned his friend Leonid Toptunov, on the senior reactor control engineer’s desk of Unit Four. But nobody answered. Strange, he thought. Maybe he’s busy. He tried Control Room Number Two, where the senior reactor control engineer picked up immediately.

“Good morning, Boris,” Glukhov said. “How is everything going?”

“Okay,” the engineer said. “We’re raising power on Unit Two. Parameters are normal. Nothing special to report.”

“Okay. How about Unit Four?”

There was a long silence on the line.

“We’ve been instructed not to talk about it. You’d better look out of the window.”

Glukhov went out to the balcony. The apartment was on the fifth floor, and from his position just behind the city’s new Ferris wheel, he had a decent view of the plant. But he couldn’t see much out of the ordinary. Some smoke hung in the air above Reactor Four. Glukhov had a cup of coffee and told his wife he would head to Kurchatov Street to meet the bus bringing the night shift back from the plant. They’d be able to tell him what was going on.

He waited at the bus stop, but the men from the shift never arrived. Instead, a truck filled with policemen pulled up. Glukhov asked what had happened. “It’s not clear,” the policeman said. “The wall of the reactor hall has collapsed.”

What?

“The wall of the reactor hall has collapsed.”

It was an unbelievable idea. But Toptunov would surely have an explanation.

Perhaps I just missed the bus, Glukhov thought. Leonid might already be at home.

It was less than a 15-minute walk from the bus stop to Toptunov’s apartment building. Glukhov climbed to the top floor, turned right at the head of the stairs, and walked to the door at the end of the hall: number 88, handsomely upholstered in red imitation leather. He pushed the buzzer. He pushed it again. There was no reply.

The Pripyat hospital, Medical-Sanitary Center Number 126, was a small complex of biscuit-colored buildings behind a low iron fence on the eastern edge of the city. It was well equipped to serve the growing town and its young population, with more than 400 beds, 1,200 staff, and a large maternity ward. But it hadn’t been set up to cope with a catastrophic radiation accident, and when the first ambulances began to pull up outside in the early hours of Saturday morning, the staff was quickly overwhelmed. It was the weekend, so it was hard to find doctors, and, at first, no one understood what they were dealing with: The uniformed young men being brought from the station had been fighting a fire and complained of headaches, dry throats, and dizziness. The faces of some were a terrible purple; others, a deathly white. Soon all of them were retching and vomiting, filling wash basins and buckets until they had emptied their stomachs, and even then unable to stop. The triage nurse began to cry.

By 6:00 a.m., the director of the hospital had formally diagnosed radiation sickness and notified the Institute of Biophysics in Moscow. The men and women arriving from the plant were told to strip and surrender their personal effects: watches, money, Party cards. It was all contaminated. Existing patients were sent home, some still in their pajamas, and the nurses broke open emergency packages designed for use in case of a radiation accident, containing drugs and disposable intravenous equipment. By morning, 90 patients had been admitted. Among them were the men from Control Room Number Four: Senior Reactor Control Engineer Leonid Toptunov, Shift Foreman Alexander Akimov, and their dictatorial boss, Deputy Chief Engineer Anatoly Dyatlov.

At first, Dyatlov refused treatment and said he only wanted to sleep. But a nurse insisted on putting in an IV line, and he began to feel better. Others, too, seemed not to have been too badly injured. Senior mechanical engineer Alexander Yuvchenko felt dizzy and excited but soon fell asleep, woken only when a nurse came to attach a drip. He recognized her as a neighbor from his apartment building and asked her to find his wife when she finished her shift, to reassure her that he would be home soon. In the meantime, Yuvchenko and his friends tried to estimate how much radiation they had received: They thought 20 rem, or perhaps 50. But one, a navy veteran once involved in an accident on a nuclear submarine, spoke from experience: “You don’t vomit at 50,” he said.

Vladimir Shashenok, rescued from the wreckage of the flowmeter room by his colleagues, had been one of the first to arrive. Burns and blisters covered his body, his rib cage was caved in, and his back appeared to be broken. And yet, as he was carried in, the nurse could see his lips moving; he was trying to speak. She leaned closer. “Get away from me—I’m from the reactor compartment,” he said.

The nurses cut the shreds of filthy clothing from his skin and found him a bed in intensive care, but there was little they could do. By 6:00 a.m., Shashenok was dead.

At home on Heroes of Stalingrad Street, around 8:00 a.m., Maria Protsenko heard a commotion in the apartment downstairs. Just as she did whenever she wanted to telegraph the neighbors below with important news, or to share something on the stove that was particularly tasty, Protsenko rapped on the kitchen radiator with a spoon. The response came clanging right back: Come down!

Protsenko was a small but formidable 40-year-old who wore her dark, curly hair cropped sensibly short, born in China to Sino-Russian parents, yet forged in the crucible of the USSR. Her grandfather had been arrested and disappeared into the Gulag during Stalin’s purges; when she was a baby, both her older brothers died from diphtheria because they were kept from seeing a doctor by the curfew in the Chinese border town where they lived. After that, her grief-stricken father sank into opium addiction, and her mother fled into Soviet Kazakhstan, where she raised Maria alone. A graduate in architecture from the Institute of Roads and Transport in Ust-Kamenogorsk, Protsenko had been Pripyat’s chief architect for seven years, with her own office on the second floor of the ispolkom. It was from there that she oversaw the execution of Pripyat’s new construction projects, with a profoundly un-Soviet eye for detail. Barred from Party membership by her Chinese birth, she brought an outsider’s zeal to her work. She roamed the streets with a ruler, checking on the quality of the concrete paneling in new apartment buildings. She chastised the construction workers for shoddy sidewalks: “Children will break their legs, and then how will you feel?” When persuasion wouldn’t work, she lashed them with invective. More than a few of the men were afraid of her.

Many of Pripyat’s apartments and major buildings—the Palace of Culture, the hotel, the ispolkom itself—were erected from standardized blueprints produced in Moscow and designed to be reproduced identically in every town in every corner of the USSR. But Protsenko did what she could to make them unique. In spite of the prevailing state doctrine calling for gloomy “proletarian aesthetics”—rejecting decadent Western notions of individuality in the interests of economy—she wanted them to be beautiful. Protsenko worked frugally with small supplies of hardwood, ceramic tiles, or granite to decorate the interiors of Pripyat’s public buildings, designing parquet flooring and wrought-iron screens in a botanical pattern for the restaurant, or inlaying small sections of marble in the walls of the Palace of Culture. She watched as the city grew from just two microdistricts to three, then four. She helped choose the names of the new streets as they were added, and attended to the finer points of each of the city’s new amenities. The library, the swimming pool, the shopping center, the sports stadium—all passed through her hands.

As she left her apartment that morning, Protsenko was still expecting to spend the day at the office, busy with preparations for another expansion of the city. Only the day before, she had received a delegation from the urban design institute in Kiev. Together they were planning the infrastructure of Pripyat’s sixth new district, to be constructed on reclaimed land beside the river to accommodate the workers who would operate the first reactors of plant director Viktor Brukhanov’s massive new Chernobyl Two facility. Dredging was under way, bringing up sand from the river bottom to provide the foundations of the extra neighborhoods. When they were complete, Pripyat would be home to as many as 200,000 people.

By the time Protsenko made her way to the apartment downstairs, it was past 8:00. Her 15-year-old daughter had already left for school; her husband, who worked as an automobile mechanic for the city, was still asleep in bed. She found the neighbors—her close friend Svetlana and her husband, Viktor—sitting at their kitchen table. Despite the early hour, they were drinking shots of moonshine vodka, or samogon. Svetlana explained that her brother had called from the plant. There had been an explosion.

“We’re going to chase away the shitiki!” Viktor said, raising a glass. Like many construction and energy workers at the plant, he believed that radiation created contaminated particles in the blood—shitiki—against which vodka was a useful prophylactic. Just as Protsenko was telling him that she didn’t think she could handle samogon, whatever the need, her own husband appeared in the doorway: “You’ve got a phone call.”

It was the secretary from the ispolkom. “I’m coming over,” Protsenko said.

By 9:00 a.m., hundreds of members of the militsia had been mobilized on the streets of Pripyat, and all roads into the town had been cut off by police roadblocks. But as the city’s leaders—including Protsenko, Deputy Mayor Esaulov, the Pripyat civil defense chief, and the directors of schools and enterprises—gathered for an emergency meeting at the building that housed the ispolkom, elsewhere in Pripyat the day began exactly as it would on any warm Saturday morning.

Across the city’s five schools and in the Goldfish and Little Sunshine kindergartens, thousands of children started their lessons. Beneath the trees outside, mothers walked babies in their strollers. People took to the beach to sunbathe, fish, and swim in the river. In the grocery stores, shoppers stocked up on fresh produce, sausage, beer, and vodka for the May Day holiday. Others headed off to their dachas and vegetable gardens on the outskirts of the city. Outside the cafe beside the river jetty, last-minute preparations were under way for an alfresco party to celebrate a wedding, and at the stadium, the city soccer team was warming up for an afternoon match.

Inside the fourth-floor conference hall, Vladimir Malomuzh, the Party’s second secretary for the Kiev region, took the stage. Malomuzh had arrived from Kiev just an hour or two earlier and, since the Party took precedence over government in emergency situations, was now in charge. Beside him stood the two most powerful men in the city: plant director Viktor Brukhanov and construction boss Vasily Kizima.

“There has been an accident,” Malomuzh said, but offered no further information. “The conditions are being evaluated right now. When we know more details, we’ll let you know.”

In the meantime, he explained, everything in Pripyat should carry on as usual. Children should stay at school; stores should remain open; the weddings planned that day should continue.

Naturally, there were questions. Members of the Young Pioneers of School Number Three—1,500 children in all, part of the Communist equivalent of the Scouts—were due to assemble in the Palace of Culture that day. Could they proceed with the meeting? There was a children’s health run scheduled for the following day through the streets of the city. Should that go ahead, too? Malomuzh assured the school director that there was no need for a change of plans; everything should continue as normal. “And please do not panic,” he said. “Under no circumstances should you panic.”

Adam Higginbotham is the author of the New York Times bestseller Midnight in Chernobyl: The Untold Story of the World’s Greatest Nuclear Disaster. He also writes for The New Yorker, The New York Times Magazine, Wired, GQ, and Smithsonian. He lives in New York City. Connect with him @Higginbothama or AdamHigginbotham.com.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook