The Caribbean-Americans Searching for Their Chinese Roots

Hakka Conferences are allowing distant relatives to meet and untangle their complex genealogy.

Ricardo Hoyen likes to joke that he was kidnapped. He was born in Jamaica, where he grew up in Kingston, but was sent to New York City to live with an aunt when he was 15, in 1964. “I thought I was coming to visit the World’s Fair,” he says. “I didn’t know it was to stay.”

In New York, Hoyen (who goes by the nickname Ricky) attended the High School of Commerce, located where Lincoln Center now stands. “I was accused of not speaking English because they couldn’t understand my accent,” he recalls. ”And when I said I was from Jamaica one of my teachers called me a liar.” (Hoyen also has black and European ancestry, through a French-Cuban grandmother, but is usually perceived as Chinese.) The fervor of the sixties was in full swing, and Hoyen plunged in: protesting the Vietnam War, frequenting jazz clubs, traveling south to march against the KKK, and dabbling in Harlem’s black nationalist scene, among the followers of Marcus Garvey.

Through it all, he pined for Jamaica. He often made an effort to seek out other Chinese Caribbeans, many of whom who worked in restaurants and bakeries throughout Harlem, Crown Heights in Brooklyn, and Chinatown. Like Hoyen, those people were part of a larger wave of diaspora who left the Caribbean throughout the 1960s,‘70s, and ‘80s, and now live elsewhere around the world. “I say I was kidnapped because life was wonderful in Jamaica,” Hoyen says. “If you had ever lived there, you would never want to leave.”

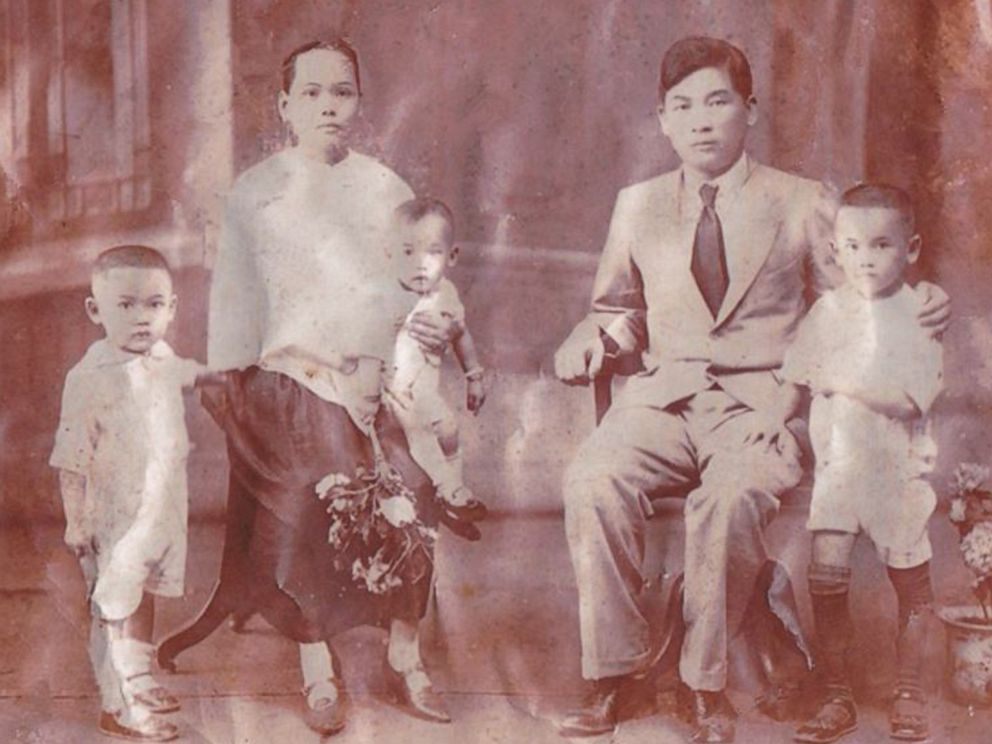

Lately, the search for connection to his past has taken Hoyen to a new annual gathering called the New York Hakka Conference, the local version of many such conferences around the world. Most Chinese who, like both of Hoyen’s grandfathers, migrated from Southern China to Jamaica throughout the 19th or early 20th century were Hakka, a group of people originating in China with a distinct set of customs and a language also called Hakka. Because of that, and because the New York Hakka Conference is organized by a woman with ties to Jamaica, the event has become a magnet for not only the usual dispersed Chinese Hakka who attend such events , but in particular for Afro-Chinese-Caribbean people who wish to learn more about their roots. The vagaries of personal relationships, the great geographic distances that members of the Chinese and Afro-Caribbean diaspora have traversed, and the twists and turns of history have meant that many such families have become separated. But some of them are looking to reconnect.

Paula Madison, the 65-year-old organizer of the New York Hakka Conference, grew up in Harlem always wondering about her Chinese grandfather, Samuel Lowe. All she knew was that he had migrated to Jamaica in 1905, established several general stores, and had Madison’s mother, Nell Vera Lowe, with a local Afro-Jamaican woman named Albertha Campbell in 1918. The couple split up when Nell was three, after Samuel Lowe said he was betrothed to a Chinese woman who was coming to Jamaica, and that he wanted to raise the child with his Chinese wife. Albertha refused, and Nell never saw her father again. When Nell was 15, she traveled to the town where his store was, and learned that he had moved back to China , after trying unsuccessfully to find her. Madison speculates he left due to a wave of anti-Chinese sentiment that flared up in Jamaica during the 1930s. His brothers, who were still in Jamaica, gave Nell a pair of pearl earrings he had left behind for her.

Nell eventually moved to the United States, where she died in 2006. But in 2012, Madison was able to track down her grandfather’s ancestral village and burial site in China, thanks to a Hakka conference she attended in Toronto. (A large proportion of Chinese Jamaicans who left the island during the 1960s and ‘70s resettled in Toronto.) During the conference, Paula approached the organizer, Jamaican-born Keith Lowe, because of his last name, and several cross-continental phone calls and emails later, the two figured out they were distant cousins from the same ancestral village in China. Madison has now gained 300 new Chinese relatives, whom she visits several times a year. She also boasts that she has successfully convinced her relatives to add her mother to the family’s 3,000-year-old jiapu, or genealogy record, which normally only includes men.

Madison has written a book and produced a documentary about her search, both called Finding Samuel Lowe. During speaking engagements about the book and film, Madison was frequently approached by people—many of them, like herself, mixed-race Americans with parents from the Caribbean and a Chinese grandfather—about how to track down their own Chinese relatives. In 2015, cousin Keith successfully convinced Madison—a retired NBC executive who gives off an immediate air of “gets things done”—to organize a New York Hakka conference. There, many people also asked for roots-seeking advice. For the second New York Hakka Conference in 2017, Madison booked representatives from several organizations in the Caribbean, the U.S., and China who help people trace their ancestry.

The Caribbean has a long history of Chinese (and Indian) migration—one intertwined with transatlantic slavery. The British first brought Chinese and Indian workers to the Islands to replace slave labor on sugar plantations after Britain abolished slavery in 1834. (Initially, they used indentured servants from Ireland and Germany, but quickly turned East.) From 1853–1884, a recorded 17,904 Chinese—mostly men from Guangdong Province in southeast China—migrated to the British West Indies as indentured laborers, according to scholar Walton Look Lai. Some 160,000 migrated to the Caribbean overall (including Cuba). They were a fraction of a much larger wave, driven by turmoil in China—political and social unrest, the Taiping Rebellion, and a population explosion—that sent some 7.5 million Chinese migrating all over the world throughout the 19th century, including 125,000 to Cuba, and 100,000 to Peru.

The experiences of indentured laborers varied. For some, it was a genuine opportunity to sail to the Caribbean, work three to five years, and return to China relatively well-off. There were also many, however, who were kidnapped or tricked into going, and died overseas under conditions not much better than slavery. Some men stayed on after their contracts ended, and through village networks, more kinsmen came to join them. In Jamaica, they rose over time to become a merchant class, heavily associated with grocery stores.

Through the decades, many Caribbeans have migrated onwards to still other countries, which has added to the difficulty families have in locating each other. Both the U.S. and the U.K. recruited workers from the Caribbean during WWI and WWII. After WWII, there was still more need for labor in Britain that the country largely filled with people from throughout its empire. The 1961 census in Great Britain showed roughly 200,000 West Indians in England, half of them from Jamaica. Many Caribbeans (as well as people from Asia) migrated to the U.S. after Congress passed the 1965 Immigration and Nationality Act, which eliminated national-origin quotas that had previously allocated the vast majority of immigration visas to people from northern and western Europe. During the 1970s, Jamaica’s growing closeness with Cuba spurred fears the island would turn communist, which caused many Jamaicans, especially Chinese Jamaicans, to leave. Many also left due to a wave of anti-Chinese violence on the island in 1965.

At a church community center in Manhattan’s Chinatown last fall, around 100 people from as far afield as Jamaica, Cuba, Mauritius, Miami, and Atlanta gathered for the second ever New York Hakka Conference. They took part in Hakka cooking demonstrations, watched a presentation about “tulou” architecture in Fujian, China, and learned about efforts to restore the Chinese cemetery in Havana.

Included among the speakers were representatives from several roots-seeking organizations. These included a Chinese Trinidadian named Felicia Chang, whose company Plantain helps people research and organize their family history into books and other story-friendly formats; a Brit named Clotilde Yap who works for a Beijing-based company called My China Roots; and Robert Hew, a member of the Chinese Benevolent Association of Jamaica, who has spent decades helping other people track down their roots in China, and only just located his own ancestral village a few months ago.

As audience members nodded and took notes, the speakers discussed the vagaries of Chinese name translation. (The surname pronounced “Qiu” in Mandarin, for example, was often rendered “Hew” or “Hugh” in Jamaica, a sort of British take on Hakka pronunciation, but might become “Yau” upon passing through Hong Kong due to Cantonese-speaking ship stewards. Still other dialects and romanization systems render it Chiu or Khoo or Khoe.) Speakers also rattled off the ins and outs of navigating records maintained by entities ranging from the Mormon Church to British shipping companies to Trinidadian newspapers. In between sessions, attendees approached them for more detailed advice.

For many Afro-Chinese-Caribbeans, tracking down the Chinese side of their family offers the best hope for learning anything about their ancestry. “I began researching the African side of my family long before the Chinese one,” Paula Madison said. “But I know much more about my Chinese grandfather than my African family. Why? Because of that ugly institution called slavery.”

Among the people taking notes at the conference was a woman in her 50s, wearing a red silk Chinese-style jacket. Later, over a lunch of oxtail stew in Chinatown, the woman, a psychiatric nurse practitioner named Carole Chin, said that like Ricky Hoyen, she had moved to the U.S. from Jamaica as a child, when her mother immigrated as a healthcare worker. She had visited China for the first time a few years earlier, and hoped to someday track down the village where her Chinese great-grandfather came from. She had a copy of his birth certificate, but felt stymied by the task of figuring out the characters of his Chinese name. She also mentioned that her desire to learn her family’s history was spurred in part by the death of her brother. Hoyen, too, had said that he felt compelled to attend the conference because his aunt—the person who had been the family historian, whom everyone went to with questions about the past—had died.

“I think to my relatives in Jamaica, it’s not interesting, because they’re used to it,” Chin said. “For them it’s like, yeah there are Chinese people here, we’re intermarried with Chinese—so what? It’s those of us who have left who are curious. Because we’re all in America and feeling different.” She also spoke glowingly about her experience at the Hakka Conference. “I’m a New Yorker, so I go to Chinatown all the time,” she said. But the conference activities had made her feel more connected to a neighborhood—and city—that for more than a century, has served as a crossroads of migration from around the world. “I feel like it’s my home now,” she said. “I really feel like: this is my place.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook