The Christmas Tree Is One of the World’s Oldest and Most Evergreen Traditions

Long before your living room’s seasonal centerpiece, cultures around the world marked the darkest time of year with palms, pines, and other greenery.

This story was originally published on The Conversation and appears here under a Creative Commons license.

Why, every Christmas, do so many people endure the mess of dried pine needles, the risk of a fire hazard, and impossibly tangled strings of lights?

Strapping a fir tree to the hood of my car and worrying about the strength of the twine, I sometimes wonder if I should just buy an artificial tree and do away with all the hassle. Then my inner historian scolds me: I have to remind myself that I’m taking part in one of the world’s oldest religious traditions. To give up the tree would be to give up a ritual that predates Christmas itself.

Almost all agrarian societies independently venerated the Sun in their pantheon of gods at one time or another. There was the Sol of the Norse, the Aztec Huitzilopochtli, the Greek Helios. The solstices, when the Sun is at its highest and lowest points in the sky, were major events. The winter solstice, when the sky is its darkest, has been a notable day of celebration in agrarian societies throughout human history. The Persian Shab-e Yalda, Dongzhi in China and the North American Hopi Soyal all independently mark the occasion.

The favored décor for ancient winter solstices? Evergreen plants. Whether as palm branches gathered in Egypt in the celebration of Ra or wreaths for the Roman feast of Saturnalia, evergreens have long served as symbols of the perseverance of life during the bleakness of winter, and the promise of the Sun’s return.

Christmas came much later. The date was not fixed on liturgical calendars until centuries after Jesus’ birth, and the English word Christmas—derived from “Christ’s Mass”—would not appear until over 1,000 years after the original event.

While December 25 was ostensibly a Christian holiday, many Europeans simply carried over traditions from winter solstice celebrations, which were notoriously raucous affairs. For example, the 12 days of Christmas commemorated in the popular carol actually originated in ancient Germanic Yule celebrations.

The continued use of evergreens, most notably the Christmas tree, is the most visible remnant of those ancient solstice celebrations. Although Ernst Anschütz’s well-known 1824 carol dedicated to the tree is translated into English as “O Christmas Tree,” the title of the original German tune is simply “Tannenbaum,” meaning fir tree. There is no reference to Christmas in the carol, which Anschütz based on a much older Silesian folk love song. In keeping with old solstice celebrations, the song praises the tree’s faithful hardiness during the dark and cold winter.

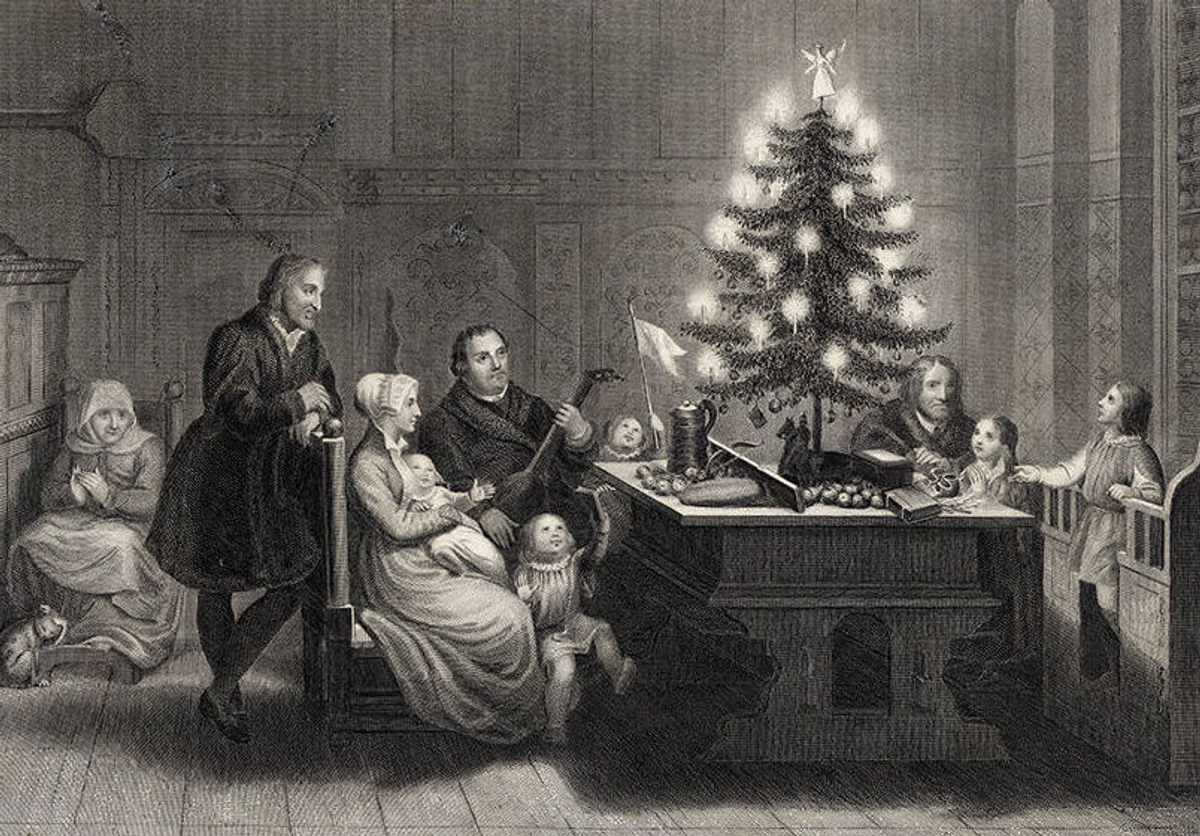

Sixteenth-century German Protestants, eager to remove the iconography and relics of the Roman Catholic Church, gave the Christmas tree a huge boost when they used it to replace Nativity scenes. The religious reformer Martin Luther supposedly adopted the practice and added candles.

But a century later, the English Puritans frowned upon the disorderly holiday for lacking biblical legitimacy. They banned it in the 1650s, with soldiers patrolling London’s streets looking for anyone daring to celebrate the day. Puritan colonists in Massachusetts did the same, fining “whosoever shall be found observing Christmas or the like, either by forbearing of labor, feasting, or any other way.”

German immigration to the American colonies ensured that the practice of trees would take root in the New World. Benjamin Franklin estimated that at least one-third of Pennsylvania’s white population was German before the American Revolution. Yet the German tradition of the Christmas tree blossomed in the United States largely because of Britain’s German royal lineage.

Since 1701, English kings had been forbidden from becoming or marrying Catholics. Germany, which was made up of a patchwork of kingdoms, had eligible Protestant princes and princesses to spare. Many British royals privately maintained the familiar custom of a Christmas tree, but Queen Victoria—who had a German mother as well as a German grandmother on her father’s side—made the practice public and fashionable.

Victoria’s style of rule both reflected and shaped the outwardly stern, family-centered morality that dominated middle-class life during the era. In the 1840s, Christmas became the target of reformers like novelist Charles Dickens, who sought to transform the raucous celebrations of the largely sidelined holiday into a family day in which the people of the rapidly industrialized nation could relax, rejoice, and give thanks.

His 1843 novella, “A Christmas Carol,” in which the miserly Ebenezer Scrooge found redemption by embracing Dickens’s prescriptions for the holiday, was a hit with the public. While the evergreen décor is evident in the hand-colored illustrations Dickens specially commissioned for the book, there are no Christmas trees in those pictures.

Victoria added the fir tree to family celebrations five years later. Although Christmas trees had been part of private royal celebrations for decades, an 1848 issue of the London Illustrated News depicted Victoria with her German husband and children decorating one as a family at Windsor Castle.

The cultural impact was almost instantaneous. Christmas trees started appearing in homes throughout England, its colonies, and the rest of the English-speaking world. Dickens followed with his short story “A Christmas Tree” two years later. During this period, America’s middle classes generally embraced all things Victorian, from architecture to moral reform societies.

Sarah Hale, the author most famous for her children’s poem “Mary had a Little Lamb,” used her position as editor of the best-selling magazine Godey’s Ladies Book to advance a reformist agenda that included the abolition of slavery and the creation of holidays that promoted pious family values. The adoption of Thanksgiving as a national holiday in 1863 was perhaps her most lasting achievement. It is closely followed by the Christmas tree.

While trees sporadically adorned the homes of German immigrants in the U.S., it became a mainstream middle-class practice when, in 1850, Godey’s published an engraving of Victoria and her Christmas tree. A supporter of Dickens and the movement to reinvent Christmas, Hale helped to popularize the family Christmas tree across the pond.

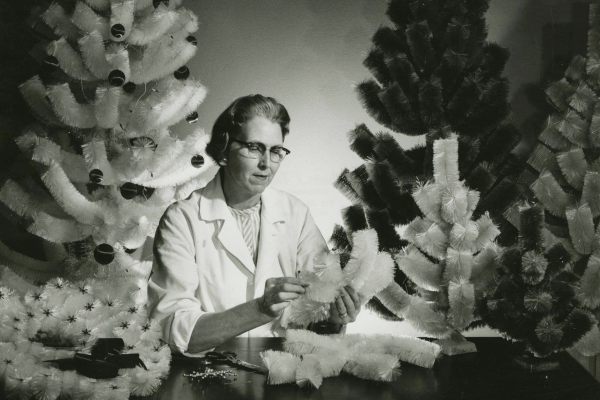

Only in 1870 did the United States recognize Christmas as a federal holiday. The practice of erecting public Christmas trees emerged in the U.S. in the 20th century. In 1923, the first one appeared on the White House’s South Lawn. During the Great Depression, famous sites such as New York’s Rockefeller Center began erecting increasingly larger trees.

As both American and British cultures extended their influence around the world, Christmas trees started to appear in communal spaces even in countries that are not predominately Christian. Shopping districts in Dubai, United Arab Emirates, Hong Kong and Tokyo now regularly erect trees.

The modern Christmas tree is a universal symbol that carries meanings both religious and secular. Adorned with lights, they promote hope and offer brightness in literally the darkest time of year for half of the world. In that sense, the modern Christmas tree has come full circle.

Troy Bickham is a professor of history at Texas A&M University.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook