A Brief History of the ‘Danse Macabre’

Skeletons have been dancing people to their graves since at least 1424.

In 2017, Saturday Night Live introduced us to David S. Pumpkins, a dancing man in a jack-o-lantern suit who, along with two skeletons, inexplicably shows up on floor after floor of a haunted elevator. He is, he tells the bemused couple seeking Halloween frights, his own thing. “And the skeletons?” they ask in reply. “Part of it!” shout the skeletons. David S. Pumpkins might indeed be his own thing, but whether they knew it or not, the Saturday Night Live writers who came up with those dancing skeletons were tapping into an image with a very long history: the Danse Macabre, a medieval allegory about the inevitability of death.

In the Danse Macabre, or Dance of Death, skeletons escort living humans to their graves in a lively waltz. Kings, knights, and commoners alike join in, conveying that regardless of status, wealth, or accomplishments in life, death comes for everyone. At a time when outbreaks of the Black Death and seemingly endless battles between France and England in the Hundred Years’ War left thousands of people dead, macabre images like the Dance of Death were a way to confront the ever-present prospect of mortality.

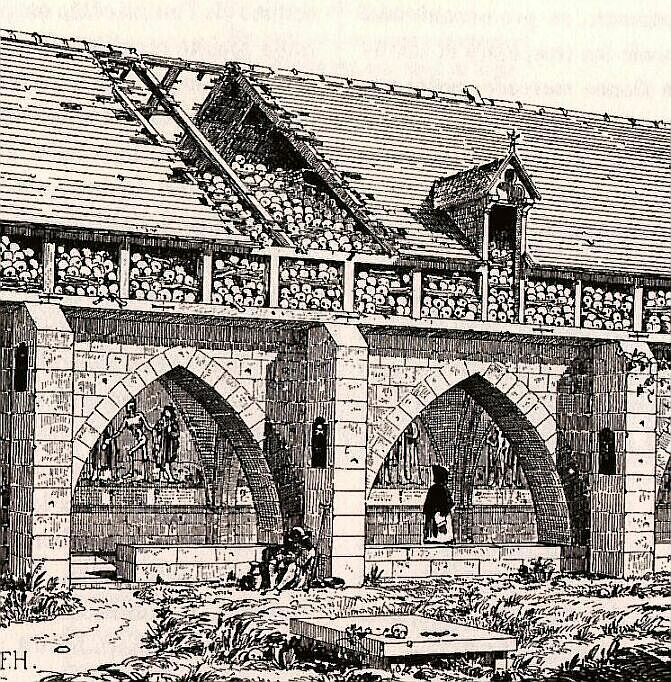

Though a few earlier examples exist in literature, the first known visual Dance of Death comes from around 1424. It was a large painting in the open arcade of the charnel house in Paris’s Cemetery of the Holy Innocents. Stretched across a long section of wall and visible from the open courtyard of the cemetery, the painting depicted human figures (all male) accompanied by cavorting skeletons in a long procession. A verse inscribed on the wall below each of the living figures explained the person’s station in life, arranged in order of social status from pope and emperor to shepherd and farmer. Clothing and accessories, like the pope’s cross-shaped staff and robes, or the farmer’s hoe and simple tunic, also helped identify each person.

Located in a busy part of Paris near the main markets, the cemetery wouldn’t have been a quiet, peaceful place of repose like the burial grounds we’re used to today, nor would it have been frequented only by members of the clergy. Instead, it was a public space used for gatherings and celebrations attended by all sorts of different people. These cemetery visitors, on seeing the Dance of Death, would certainly have been reminded of their own impending doom, but would also have likely appreciated the image for its humorous and satirical aspects as well. The grinning, dancing skeletons mocked the living by poking fun at their dismay and, for those in positions of power, by making light of their high status. Enjoy it now, the skeletons implied, because it’s not going to last.

Inspired by the painting in Paris, more depictions of the Dance of Death popped up over the course of the 1400s. According to the art historian Elina Gertsman, the imagery first spread throughout France and then to England, Germany, Switzerland, and parts of Italy and eastern Europe. Though some of these frescos, murals, and mosaics survive to the present day, many others have been lost and are now only known through archival references.

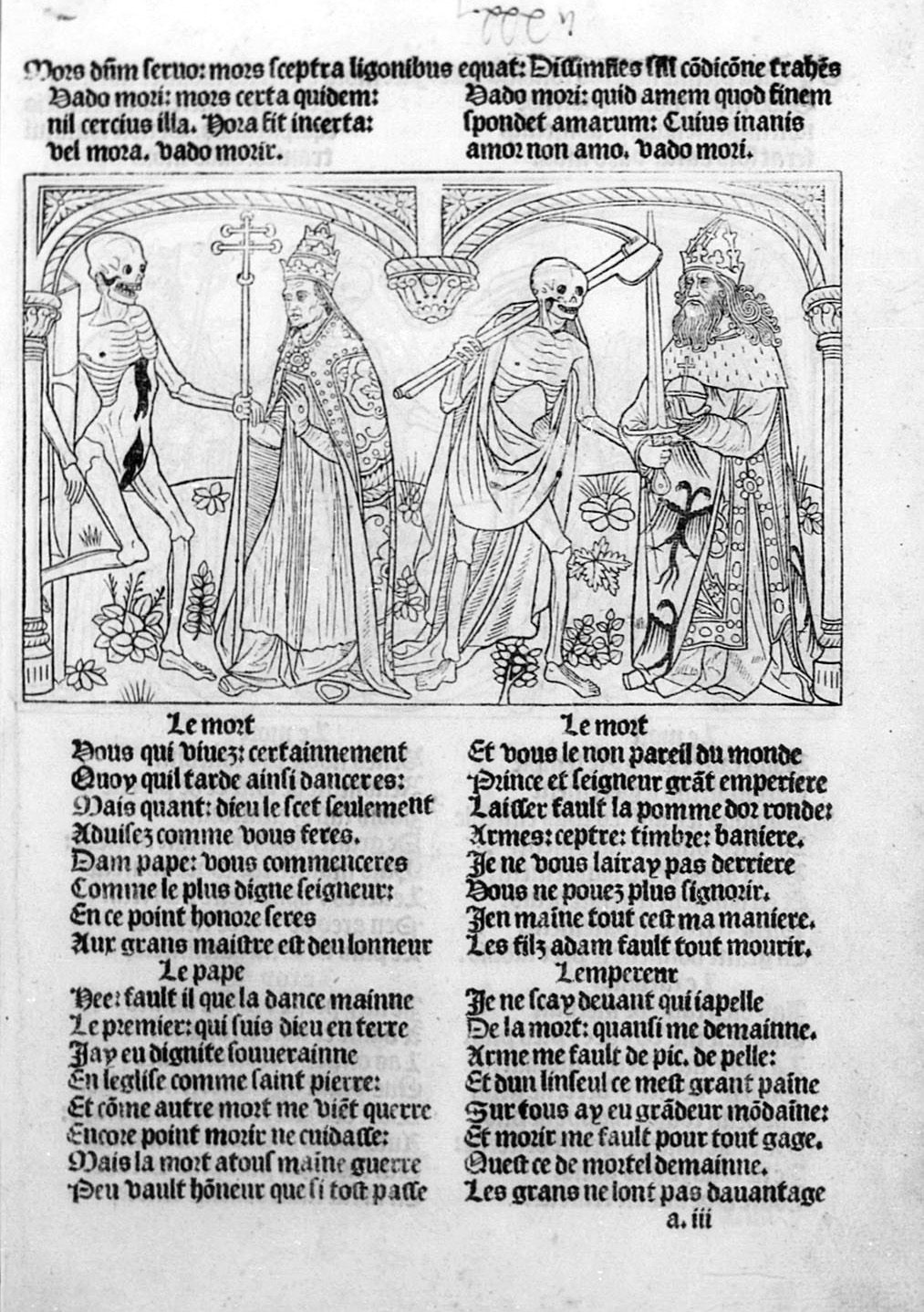

In Paris, neither the charnel house nor the cemetery still exists. (The charnel house was demolished in 1669 to widen a nearby street and the cemetery was closed in the 1780s due to overcrowding.) But the painting lives on as a set of woodcuts created by printer Guyot Marchant in 1485. Marchant’s manuscript replicates each figure in the procession as well as the accompanying verses. After the prints proved popular he went on to make several more editions, including the Danse Macabre des Femmes, a version including women, and an expanded version with ten new characters not found in the original.

As the subject’s popularity continued into the early 1500s, other artists and printers made their own versions of the Dance of Death. The best known of these is a series created by artist Hans Holbein the Younger from 1523 to 1526, first sold as individual woodcuts and then published in book form in 1538. Holbein’s series begins with the very first appearance of Death, after Eve ate the apple and humanity got kicked out of the Garden of Eden, and ends with Death’s final bow at the Last Judgment, when everyone who has ever died reappears again to be sentenced to eternity in heaven or hell.

In between, Holbein shows how Death can strike at any moment, regardless of social status or earthly power. His depictions of the different characters meeting their doom are more pointed than Marchant’s versions. Instead of dancing, the skeletons in this Dance of Death mete out justice, going after their victims in situations that highlight suggested hypocrisies and immorality. A nun, for example, kneels in prayer but looks over her shoulder at her lover while Death snuffs out the candle behind her. And in many of the scenes, peasants and beggars are ignored by the bishops, judges, or kings who are supposed to protect and care for them. Holbein explicitly addresses the peasant’s dismal treatment at the hands of his social superiors in the image of his final character, an elderly farmer kindly helped along by a skeleton. Unlike the rich and powerful, for whom Death represents a loss of status and wealth, the peasant finds relief in dying after a life of hard labor and exploitation.

Holbein’s version of the Dance of Death proved so popular that by the time he died in 1543, dozens of pirated editions were circulating in addition to the official printings. Although the large, public murals, carvings, and frescos which originally depicted the Dance of Death went mostly out of fashion after the 1500s, Holbein’s prints have remained well-known until the present day. Artists continued to find inspiration in the Dance of Death theme over the next few centuries, changing styles and formats to suit their times.

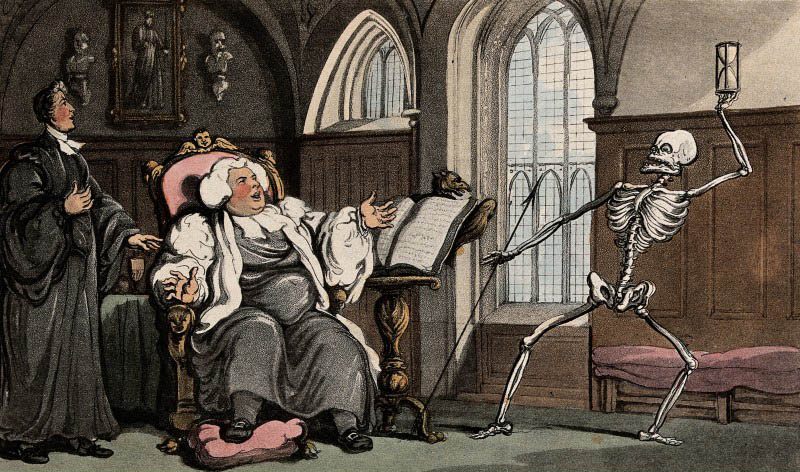

From 1814 to 1816, the English artist Thomas Rowlandson published The English Dance of Death, a series of satirical cartoons in which stereotypical caricatures of English men and women are teased by skeletons with fittingly satirical and cruel fates. A character labeled “The Glutton” dies of overeating, an apothecary is poisoned with his own medicine, and reckless young men driving too fast overturn their carriages. Like the painting and Marchant’s versions, the cartoons were accompanied by verses, written by the comic poet William Combe under the pen name “Doctor Syntax.”

In 1861, French artist James Tissot explored the subject in a painting exhibited at the Salon in Paris, depicting a line of human dancers with skeletons at the head and tail end of the procession. At the front, two musicians flank the cadaver, who looks directly out of the painting towards us, the viewers. At the end, a shrouded skeleton carries a coffin, hourglass, and scythe. The dancers, oblivious both to the specters around them and the open graves in the rocks near their feet, frolic merrily through the landscape.

Almost seven decades later, in 1929, even Walt Disney crafted his own adaptation of the allegory with “The Skeleton Dance,” an animated short in which skeletons rise from their graves and dance to a lively foxtrot. At times, the music is played on instruments made from their own bones. Though no humans are danced to their graves in this cartoon, the expressive skeletons wouldn’t look out of place in earlier Dances of Death. Other Halloween staples—black cats, owls, tombstones, and bats—add to the spooky mood.

Though the Dance of Death isn’t, strictly speaking, associated with Halloween, the macabre imagery resonates with the holiday’s connections between life and death. Skeletons, skulls, and corpses reminiscent of those grim medieval dancers often show up in haunted houses, as yard decorations, and as costumes. Sometimes grisly, sometimes cartoonish, today’s dancing skeletons are far removed from their predecessors in the Danse Macabre. But, as sanitized and commercialized as Halloween can be, it’s still a holiday that brings a greater awareness of death and forces us to confront our own mortality, even if the frights all vanish when November 1st rolls around.

At the end of the Saturday Night Live sketch, David S. Pumpkins’ skeletons appear by themselves, still dancing even without their main character. When they finish, Pumpkins himself, from behind the perplexed couple asks, “Any questions?” They scream, finally getting the scare they wanted when they got on the haunted elevator. Once the terror subsides and their hearts stop racing, they’ll go about their day, able to ignore the realities of death far more easily than the citizens of Paris could back in the 1400s.

But even after David S. Pumpkins and his skeletons are long gone, there will be another Halloween, reminding us year after year that no matter what, death’s still waiting.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook