The Dark Art of Displaying Deep-Sea Fish

How one museum keeps a rare Pacific footballfish looking sharp.

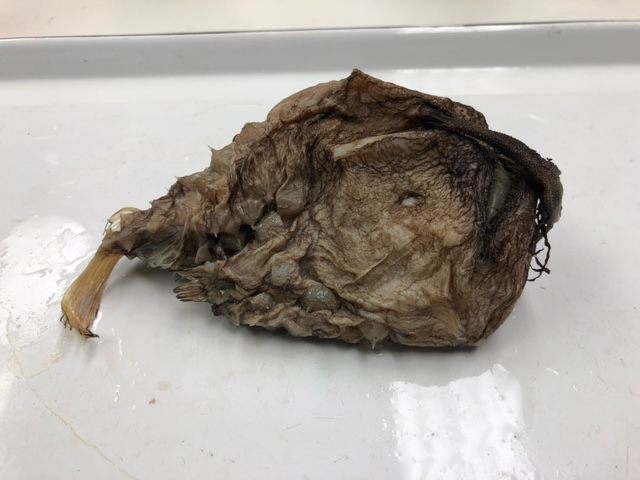

When the staff at the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County first got their hands on their new Himantolophus sagamius, an anglerfish also known as the Pacific footballfish, it was hard to make sense of the specimen’s appearance. After the deep-sea dweller washed up on the shore of Crystal Cove State Park in May, someone promptly stashed it in a garbage bag and tucked it in the freezer. By the time William Ludt, assistant curator of ichthyology, finagled the fish for the museum’s collection and drove his truck down to retrieve it, the creature looked like “a frozen block,” he says. It was dark, roundish, and frozen solid—a bit like a freezer-burned hamburger.

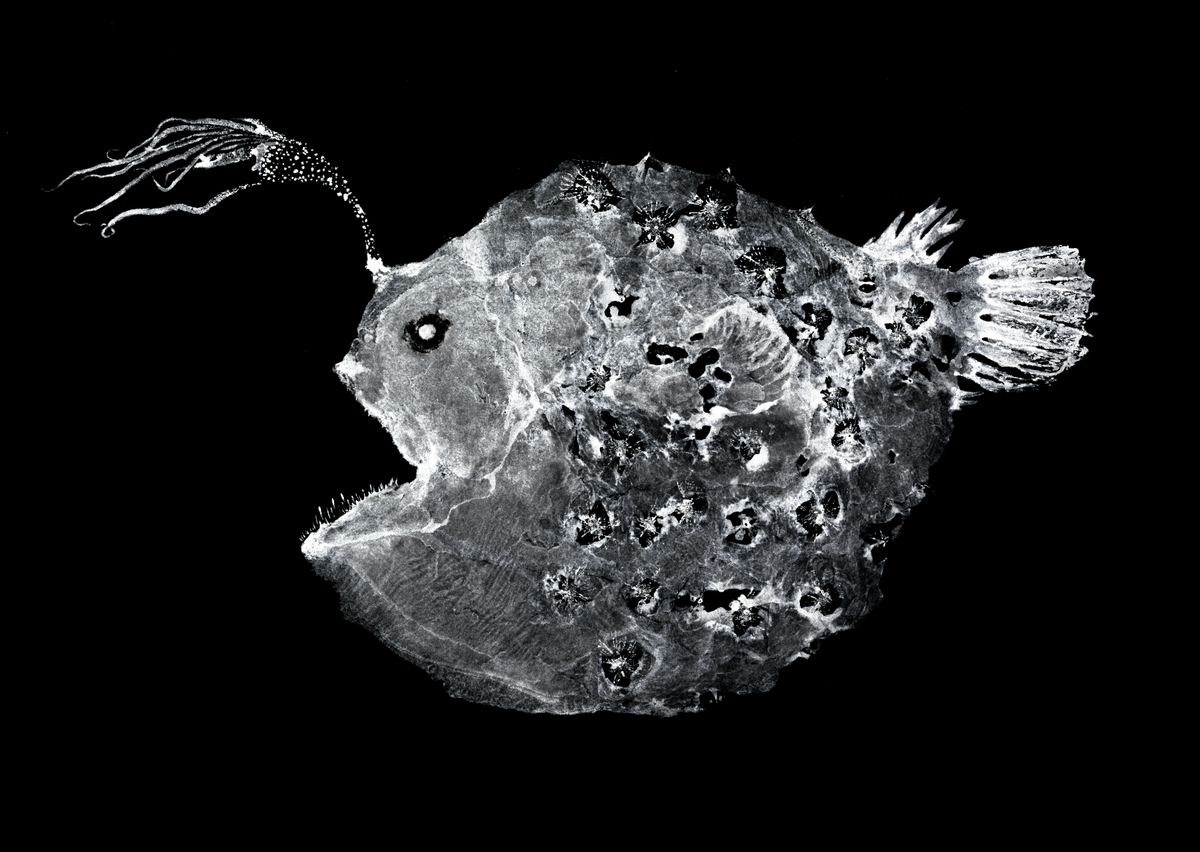

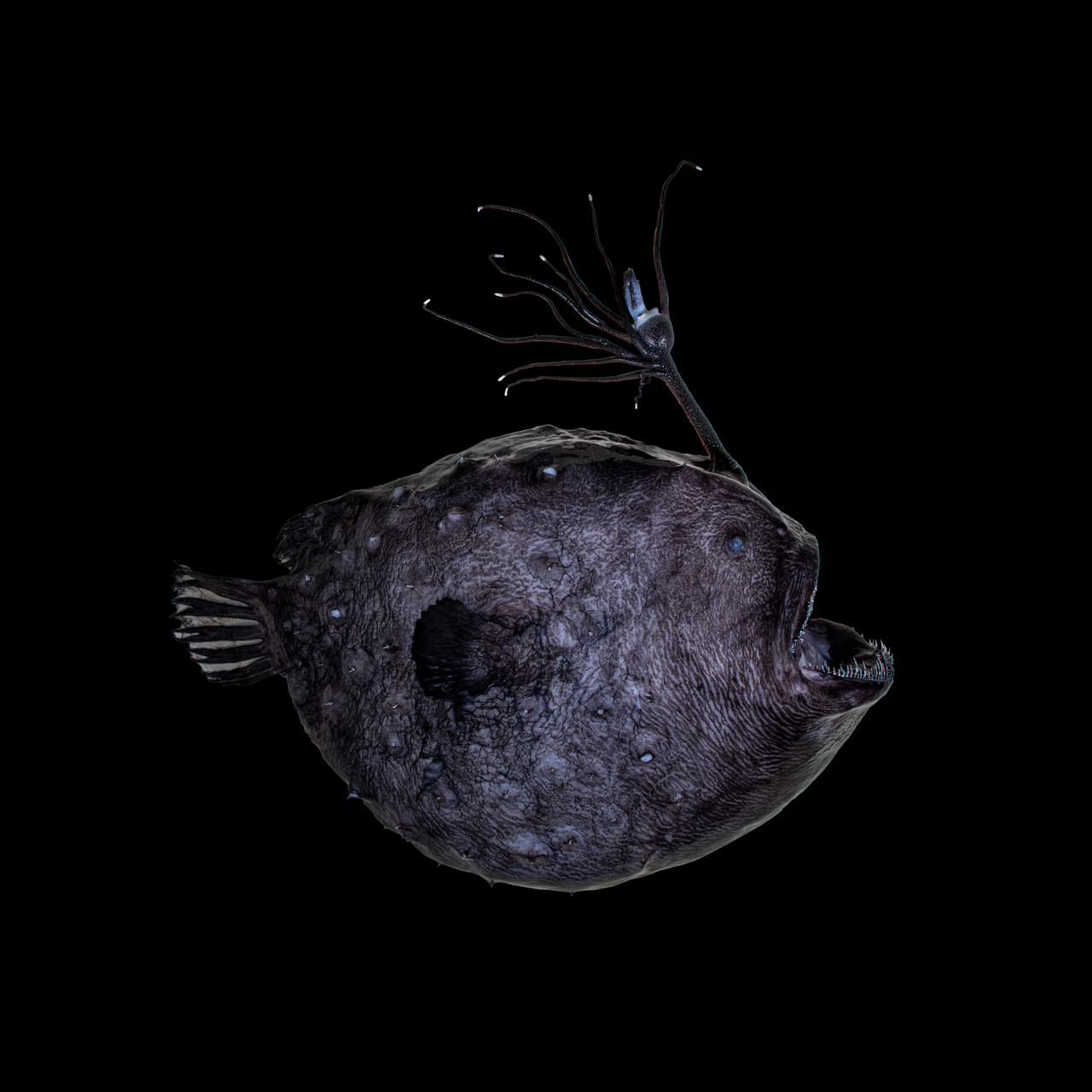

That was fine by Ludt: Freezing the fish arrested decay and kept its body safe from hungry seagulls, and the scientist wanted to do whatever he could to keep it pristine. Judging by pictures Ludt saw online when the fish first washed in, the specimen was stunning. Around a foot long, it was basically as large as the females of the species can grow, and it was dotted with bucklers, little plates with spines that resemble cactus needles and are sharp enough to pierce rubber gloves. Its body was still coal-colored and flanked by a fringed esca, a feature the fish uses as a lure, that looked like fleshy kelp with its tips dipped in silver—“like my hair in high school,” jokes Todd Clardy, the ichthyology collections manager.

This was a rare opportunity; deep-sea fish don’t often surface in great shape. Their gelatinous bodies and thin bones are easily mangled in nets, damaged by hooks, and maimed by bites. “We couldn’t get luckier to have a fish in this condition,” Ludt says. But keeping a deep-sea specimen—even a dead one—on land requires a great deal of delicate effort. Swimming 1,000 to 4,000 feet beneath the surface, Pacific footballfish are accustomed to dark, frigid water, where the pressure is immense. Up here with us, it’s a different story. So when the team decided to display this specimen for a few months in the museum gallery, they knew they’d need some creative interventions to keep it looking its best.

First, they had to melt the ice safely. After collecting the fish from the park’s freezer, Ludt transferred it to a cooler stuffed with ice packs and drove it an hour north to the museum. There, it went into the fridge and was spritzed with water as it thawed to prevent its skin from cracking, its fins from curling, and its fragile lure from turning brittle and snapping off. That took a day or so, and while it was still partly frozen, artist Dwight Hwang made a gyotaku print of the fish to memorialize it at its peak.

Preserving fish is always a slippery task, explains James Maclaine, senior fish curator at the Natural History Museum in London. The end goal is typically to have the specimen submerged in a jar of 70 to 75 percent ethanol, but it takes several steps to get there. “You can’t simply put a fish in 70 percent and consider it preserved,” Maclaine says. Specimens are typically fixed in formalin and then moved sequentially into higher and higher alcohol concentrations; conservators sometimes inject preservatives into the fish’s body, too. Oils can leach over time, especially from salmon and tuna, and museum staff must also battle evaporation, when alcohol escapes the jars.

Deep-sea residents pose additional problems. The fish are adapted to life in inky waters, where bioluminescence is one of the few sources of light. (Female Pacific footballfish light their way and attract delicious fish and squid with their lure, which is crowded with symbiotic bacteria.) Flooded with sunshine and lights on the bright surface, colors fade quickly—reds, oranges, and yellows can mellow in a matter of weeks. Darker colors are more persistent, but they eventually disappear, too. Another footballfish that has been in the collection of the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County since 1983 is now the whitish-gray of sudsy dish water (and, Clardy adds, it looks deflated, “shriveled into a little blob”). A 1980s-era specimen in the California Academy of Sciences looks similarly bleached.

To stave off fading, the team needed to prevent this new fish from being bombarded with constant light. They installed a motion sensor that flicks on a light only when someone approaches. Because the fish is too floppy to position as if it were swimming—“it would have collapsed under its own weight,” Ludt says—the museum is displaying it on its side. The exhibitions team installed angled mirrors to make it easier for viewers to see and built a recessed plastic case that curbs the risk of condensation impeding people’s view. These were all custom solutions for this fish, but Ludt now thinks of the display as a trial run, too—a proof-of-concept for ideas they could trot out again in the future.

The fish went on view at the end of August and will retire to the storage facility just after Thanksgiving. Ludt says that, however gingerly the team is treating the fish in the interim, it may already be changing a little, its colors leaching out into the alcohol prepared fresh for the bath. “I bet if we compared the alcohol in three months to [that batch], what we recovered would be a little bit yellowed,” Clardy says. It’s hard to strong-arm entropy. That’s why “the time to display it is now,” Ludt says. “In all its glory.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook