Six Stories of Stunning Passports From Countries That No Longer Exist

Yesterday’s bureaucracy is today’s curiosity.

British Palestine. The USSR. The Free State of Fiume. History is rife with states that simply didn’t make it: ones, thanks to the precariousness of politics, that eventually switched names, changed hands, or disappeared altogether.

Tom Topol has been collecting passports for 14 years, and runs the website passport-collector.com, a repository of travel documents through the ages. Topol first became fascinated by old passports after a chance encounter with some at a flea market in Kyoto, Japan. “Today our passports are uniform,” he says, “but look at an old passport [from the] 19th century—at that time they were really some kind of art.” He has spent last decade and a half learning everything he can about the politics and geography of historical passports, as well as digging into the stories of individual booklets and their bearers.

One of his specialties is passports from these has-been countries. “Such documents are historical treasures, reflecting the politics and geography of that time,” he says. Plus, with their soft-focus photos, curly signatures, and colorful stamps, they tend to be a lot prettier than our own drab travel documents.

Defunct passports may be no help when you’re trying to cross a border—but they’re great tools for traveling back in time. Here are six from Topol’s collection, with some hints at the history they illuminate.

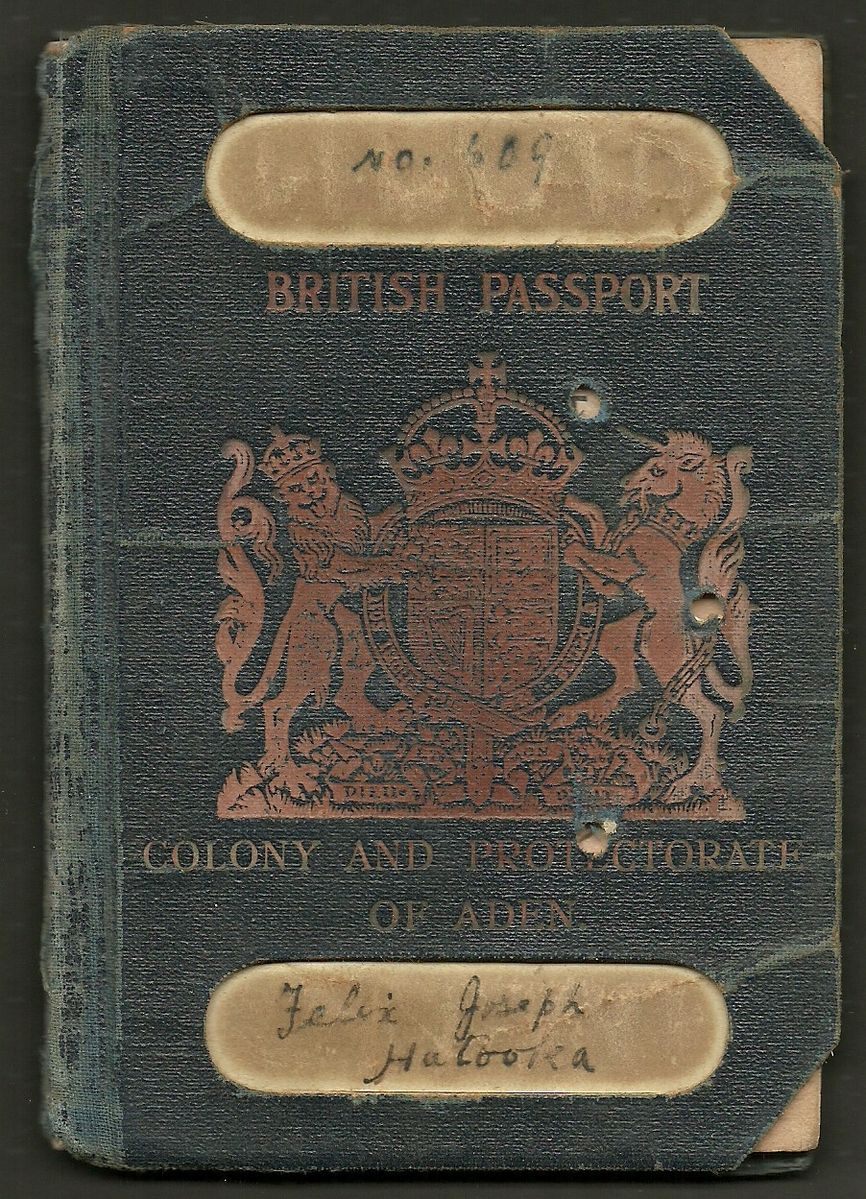

Colony and Protectorate of Aden, 1956

Rifle through the collection of a passport completist, and you’ll notice that a lot of the covers sport the same coat of arms: a lion and a unicorn flanking a shield. That’s because—surprise!—they’re all from British colonies. “The British Empire issued passports in almost all of their territories,” says Topol. “Collectors [are] always searching for these treasures,” some of which are rarer than others—North Borneo, for example, is a prize find.

This particular passport, whose cover sports the familiar lion-and-unicorn, is from the Colony and Protectorate of Aden, one former identity of what is now Yemen. Like Zanzibar and India, the Aden Protectorate was never formally annexed by Britain—instead, in the late 1800s, the Crown decided they wanted to control the Port of Aden, and began moving into the area. Tribes around the Port then granted the Crown control over their foreign affairs in exchange for military protection.

This agreement is reflected in the passport’s interior, which promises its bearer “the protection of Her Majesty’s Government,” and reads from left to right. In contrast, although the current Yemeni passport also has English and Arabic titles, the inside reads from right to left—and the Yemeni seal is on the front.

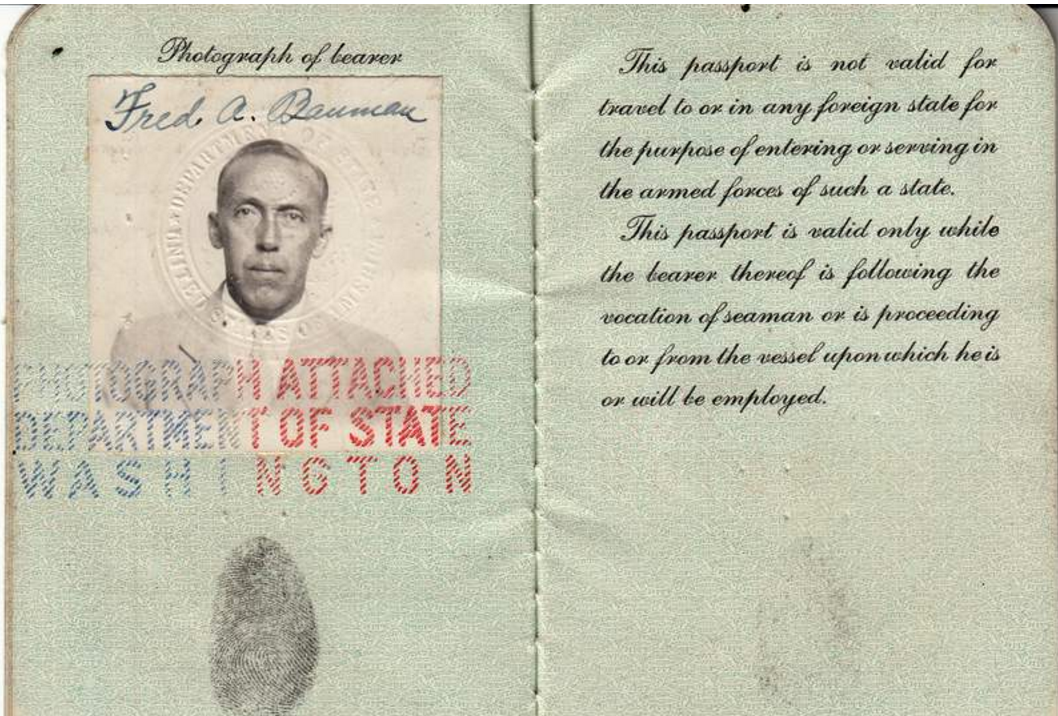

US Seaman’s Passport, 1942

Fred Albert Bauman—a narrow-faced American with mischievous eyebrows—received his special Seaman Passport on Halloween, 1942. Although not technically from a defunct country, the Seaman Passport nonetheless illuminates a bygone era—as Topol explains, it was only issued from February 1942, a few months after the United States entered World War II, to August 1945, when Japan’s army surrendered.

In addition to the standard information, the sea-green passport contains extra details about Bauman, who apparently had a scar on his left palm. It also specifies that its bearer may only use it when “following the vocation of seaman.” Although Topol has seen a number of these passports, he says not many of them have very many stamps, suggesting that the seamen did most of their traveling after the war.

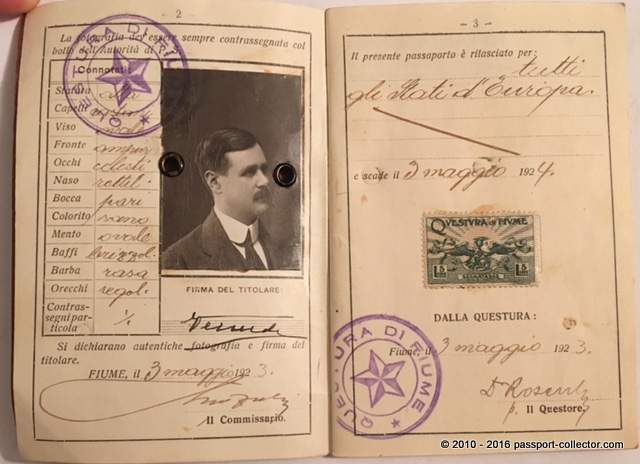

Free State of Fiume, 1923

Fiume—once a tiny state of its own, now part of Croatia—first became autonomous in 1719. Subject to the whims of various emperors and kings, it lost and regained its freedom multiple times over the course of the 18th and 19th centuries. By 1868, it was technically a part of the Kingdom of Hungary—but it was a diverse state where Italians, Hungarians, and Germans all rubbed elbows, and spoke a local dialect that was a fusion of its members’ native languages.

In 1920, in the aftermath of World War I,* Fiume was declared an official Free State—again thanks to the international community, who thought it would be good to have a buffer between Italy and what would soon become the Kingdom of Yugoslavia. It responded to its new sovereignty by remaining an unabashed melting pot. “Nationality was defined mostly by the language a person spoke,” and everyone felt more like a Fiume-ian than anything else, explains Topol. This unique loyalty was underlined by the Fiume passport, which had the country’s name on the cover in bold capitals, topped by a small, solitary star. Stamps to get back into the country had the same star, shown above in purple ink.

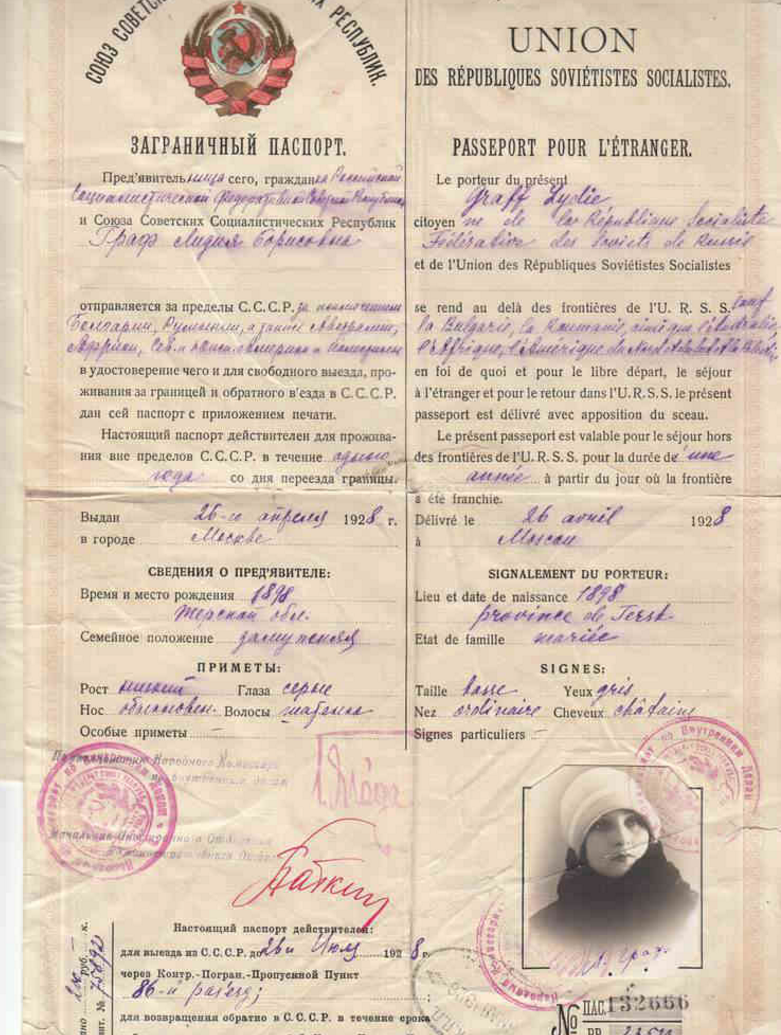

Soviet Union, 1928

Citizens of the Soviet Union used a number of different passports. An internal one, with a green cover, was issued to urban workers, and used to prevent peasants from entering the towns. This one, which belonged to a woman named Lydia Graff, was a different document that allowed for travel abroad—except to Bulgaria, Romania, Africa, the USA, and Palestine, which required extra documentation.

Graff’s passport lacks a cover, but has visas showing that she traveled to Mongolia and China. It also has a crazy bureaucratic Easter egg—the stamped signature of Genrikh Grigoryevich Yagoda, who would later become the director of Stalin’s intelligence service, and was eventually executed for alleged treason. The signature appears on the bottom left side of the page. That’s one way to get an autograph.

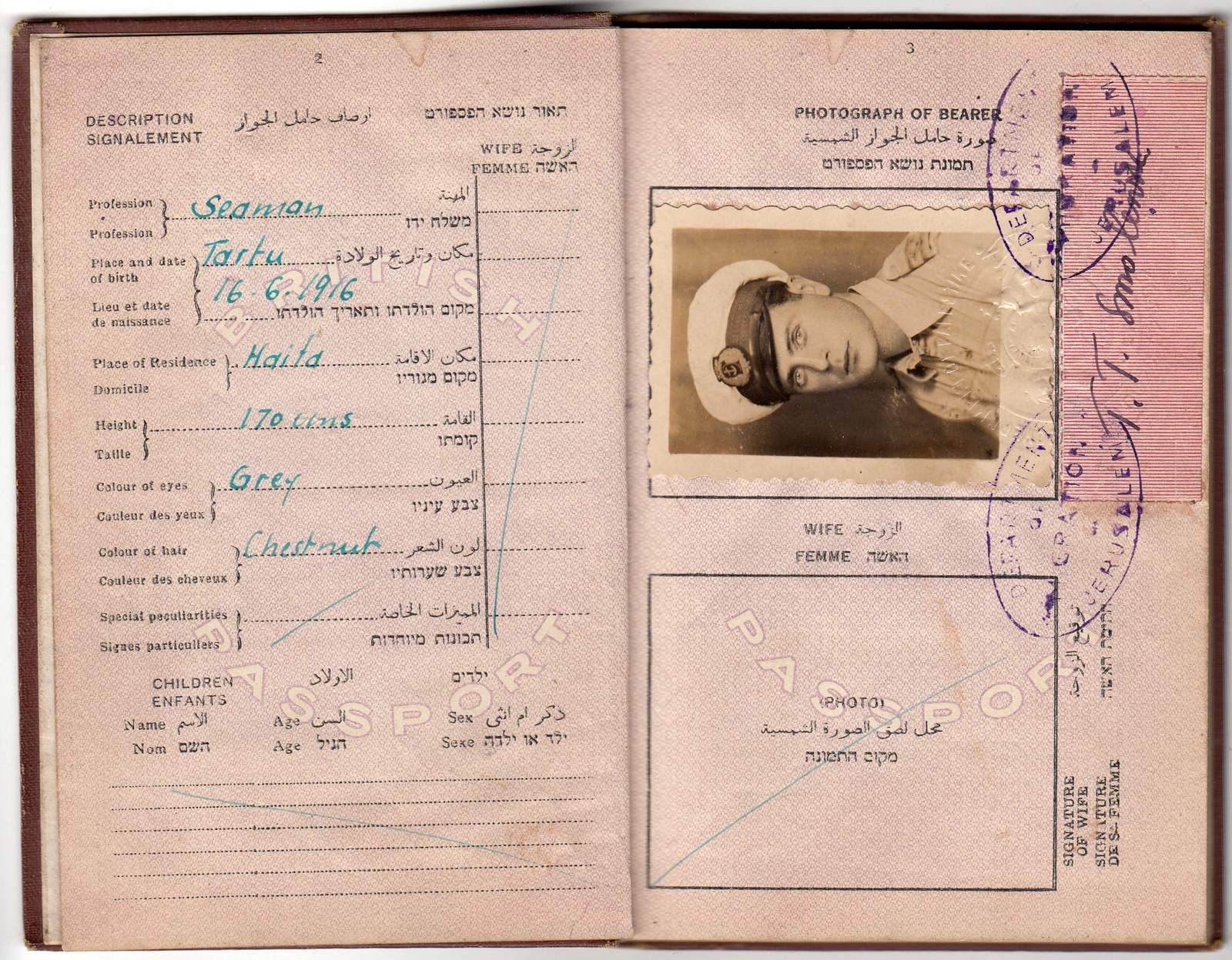

British Palestine, 1944

It’s all well and good to have a passport collection full of regular Joes. But to Topol, there’s something special about finding a document that was once used to identify someone important. Such is the case with this passport from British Palestine, which once belonged to Captain Tuve T. Smolensk. Fifteen years after it was issued, the United States Coast Guard would congratulate Smolensk on his prowess in Atlantic search-and-rescue work, calling his efforts “in keeping with the highest tradition of the sea.”

But—with no disrespect meant to Captain Smolensk—that’s not even the best thing about this passport. That honor goes to a purple stamp on page 17, which reads “Haifa”— Israel’s main port. “British Palestine turned into Israel in 1948,” explains Topol. “To find nowadays a British Palestine passport with a stamp of Israel is pretty rare.” For practical reasons, Captain Smolensk was likely allowed to keep his British Palestinian passport for a year or so after the switch, allowing for this strange convergence.

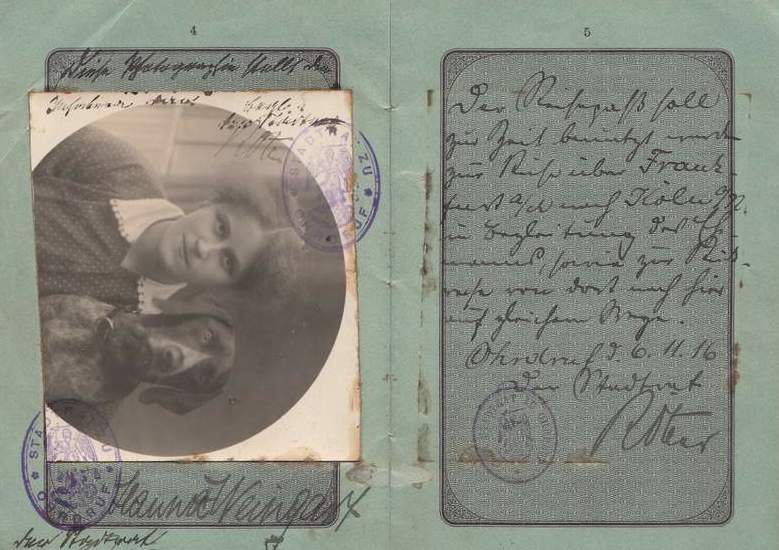

German Empire, 1916

The German Empire was comprised of various duchies, principalities, and free cities—including Duchy Saxe-Coburg-Gotha, which issued this green passport to one of its citizens in 1916, four years before it was absorbed by Bavaria.

The German Empire wasn’t a great place to be in 1916, but the government apparently attempted to make up for some of the war and hardship by allowing citizens to take passport photos with their dogs. Did this young woman travel exclusively with her pup? Where did they go? What did they see? We may never know—but thanks to this ordinary document, we now get to wonder about it.

*Correction: This article has been updated to clarify dates related to World War I.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook