The Art of Digging a Buried Building Out of Maine’s Desert Dunes

The Spring House had been hidden for decades.

On a dry day in the middle of September, Josh Smith started digging. Sometimes, the three-person crew used a track excavator; other times, they wielded shovels. They dug all day, then a few more. They removed shovelfuls of fine sand so that their hole would have gently sloping sides, like an amphitheater or a bowl. They knew that if they dug straight down, the walls could collapse in on them.

The town of Freeport, Maine, is known for outlet malls that include a 24-hour L. L. Bean. But beyond its cathedral of rubber-soled boots, Freeport is also known for its “desert,” a vast dunescape flanked by evergreens and other trees. It’s a popular tourist spot, sometimes depicted as New England’s Sahara and presided over by fake, sleepy-looking camels. That’s where Smith and his fellow shovelers carried out their work.

Smith has a background in paleontology, and is no stranger to digging. Mela and Doug Heestand, the current owners of the sprawling Desert of Maine, had tapped him to help unearth an old structure that once dispensed water from a nearby spring—a relic that hadn’t seen daylight in decades. One shovelful at a time, it started to come into view.

A desert in New England might sound like a gimmick, the kind of thing that P.T. Barnum would dream up with truckloads of sediment under the cover of night. Though the swath isn’t a desert in the geological sense—the Freeport area sees around 52 inches of rain and 71 inches of snow every year, according to the National Weather Service, and truly arid regions get much less than that—it’s not a hoax, either. The sediment didn’t arrive there by human hands.

According to the Maine Geological Survey, the sand appeared at the end of the last Ice Age. Wind barreled across the landscape from the coast, sand and silt in tow. The breeze dropped these sediments on land newly exposed by the receding ice sheet. In many cases, it was eventually hidden by plants, which helped fasten it in place. But when farmers settled the land, grazing animals exposed the sand. That’s when humans started seeing dollar signs. “Nature laid it down, human error uncovered it, and the hucksters and gawkers arrived late in the game,” The New York Times reported in 2006, with a hint of snark.

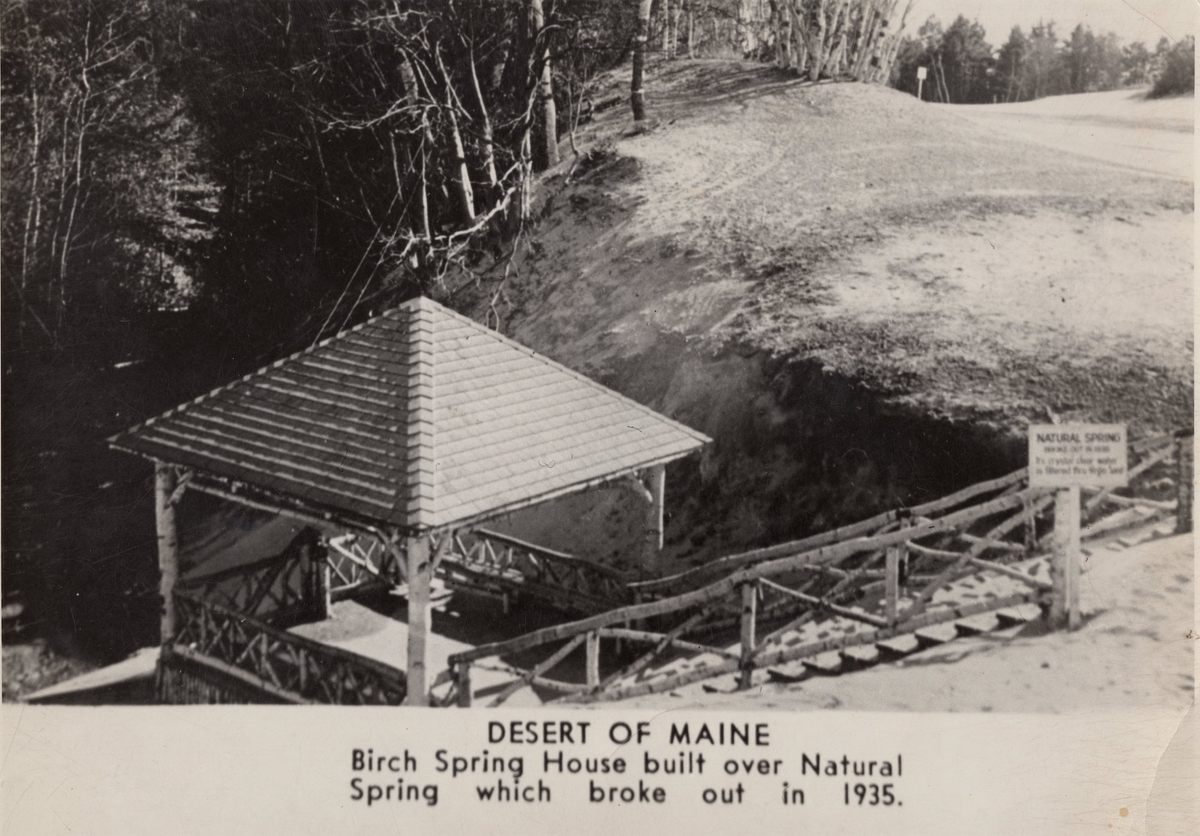

Mela Heestand, one of the current co-owners, has waded into archives and tax records to learn about the farmers who once owned the land, she explained to the local Forecaster newspaper. After that, nature-loving small business owners took over, and by 1925 it was a tourist site, the Forecaster reports. Soon, a pleasantly cold groundwater spring was discovered on the property. One 1930s visitor said it “burst forth out of one of the many mountains of powdered sand.”

At some point in the late 1930s, the then-owners of the property built a gazebo-like structure around the well-head. “For a time, visitors could go over and get a drink of water from the groundwater spring,” Smith says. And though he hasn’t seen any historic advertisements, he adds, “I would be strongly surprised if they weren’t advertising healing properties or something.”

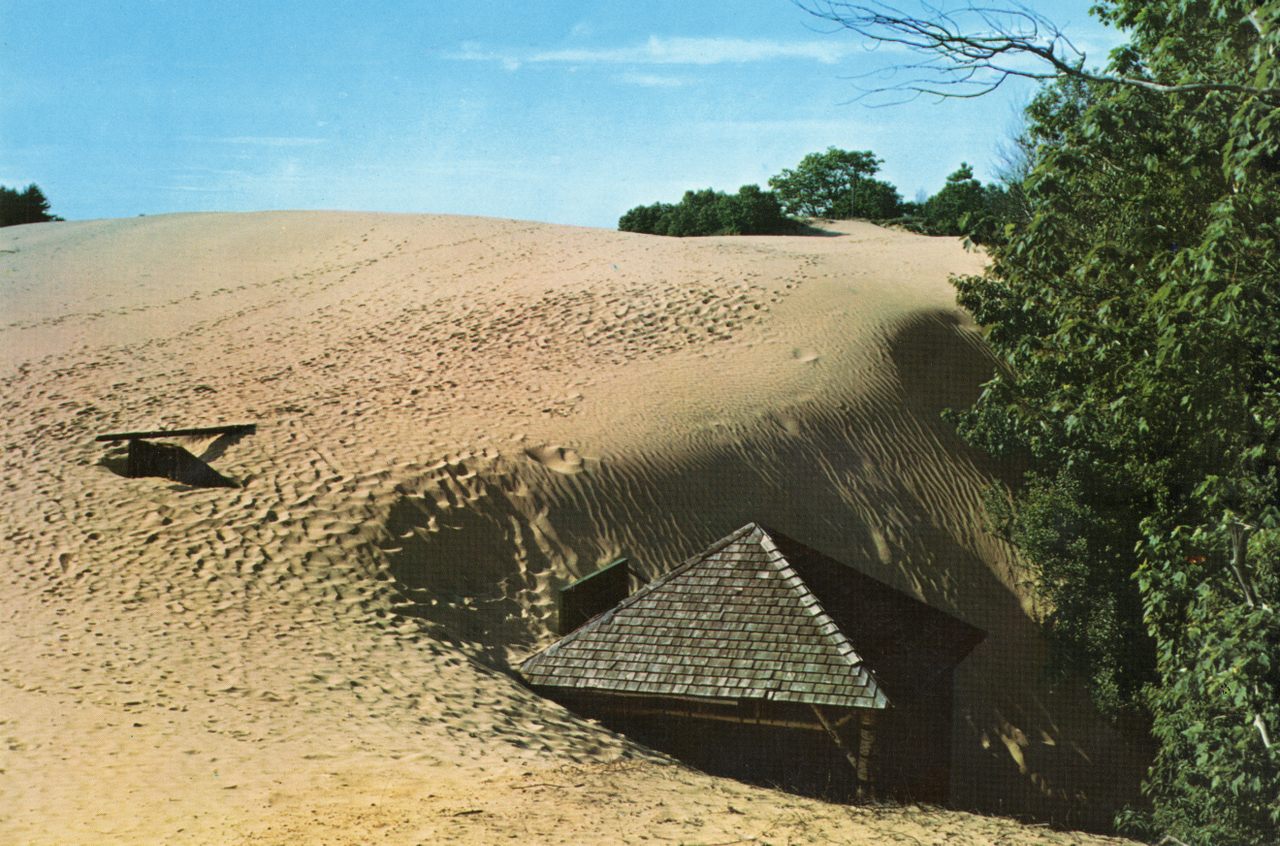

Trouble is, dunes are always on the move. The dunes at the Desert of Maine are said to have swallowed entire trees: One visitor, recounting a 1936 ramble for a New Jersey newspaper, recalled standing on dunes that had recently overtaken an apple tree, whose branches still seemed alive and jutted out through the blanket of sand. “That’s what sand dunes do, migrate from place to place,” Smith says. And the dunes marched right over the gazebo.

Smith says the gazebo structure, known as the Spring House, was likely inundated soon after it was completed. The owners didn’t try to stave off the encroaching dunes, he adds, but they did give visitors a heads-up. Sometime after World War II, they installed a sign that, in Smith’s words, said something like, “Hey, shifting sands are burying the spring house; this is unstable—stay the heck away.” By the 1960s, Smith goes on, the structure vanished beneath the dunes, and the owners installed a sign to mark its former location. “Because of the sign, we knew it was there,” Smith adds. “It wasn’t lost to history and didn’t just disappear into legend.”

When excavating in fine sediment, archaeologists cross their fingers for calm skies. “Wind will always be the enemy,” Smith says. “It will pull sand into the happy little hole you’re excavating.” On a windy day, Smith says, it’s not worth even trying to dig. “There’s no point. Might as well just go have a coffee.”

Once the heaving got underway on some of the 23 acres of exposed sand, “all we really did was shovel all bloody day long,” Smith says. They sometimes needed to strategically collapse a portion of the hole they had just dug, to prevent more from caving in on them.

They also migrated the operation 10 or 15 feet from where they began, because that’s where they came across some particularly promising artifacts—rafters that they believe once propped up the roof. “We had someone with ground-penetrating radar come out to find it, and also an old-timer who remembered where it was in the 1960s—he is the son of the man who bought the property in the 1920s—and he was actually closer to being right,” Mela Heestand says.

Smith estimates that at least 15 feet of sand have built up on top of the structure since the 1960s, and the team is still in the early stages of removing them. “We really just found the top of the roof,” Heestand says. As Maine’s famously fierce winter approaches, the crew plans to undo some of their work by covering what they have revealed with a few inches of sand, as though they were tucking the structure beneath a blanket. After the last snow and frost, they will pick the work up again.

When the excavation is complete, the owners hope to build an exhibit around the structure. They will likely preserve the sign with some sort of varnish that seals it against the elements. Walking down a ramp, visitors will encounter the heap of sand hauled from the hole, next to a cross-section of a dune, showing how the sand changed over millennia. (The oldest layer is bluish gray, Heestand says, and was once covered by an ancient, salty sea.) At the end of the ramp, after passing some signage, visitors will glimpse (but not enter) the Spring House. “The wood is fragile and experienced a lot of rot from being under wet sand for so long,” Heestand says. The owners plan to enlist a paleontologist to wire the structure together and hold it steady.

Heestand says they’ll also need a retaining wall to hold some of the sand back. Short of building a gigantic new structure over the exposed site, though, there aren’t many permanent ways to fend it off. “I think they’re going to have to employ tactful use of leaf blowers fairly continuously,” Smith says.

The dunes, meanwhile, will keep on trucking. Crawling southwest at about one foot annually, quipped writer Clif Garboden in The Boston Globe, the dunes should land on the doorstep of the Calvin Klein outlet in about 11,200 years.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook