Did an Uncredited Woman Invent Breakfast Cereal?

Before there was granola, there was granula—and billions turned out to be at stake.

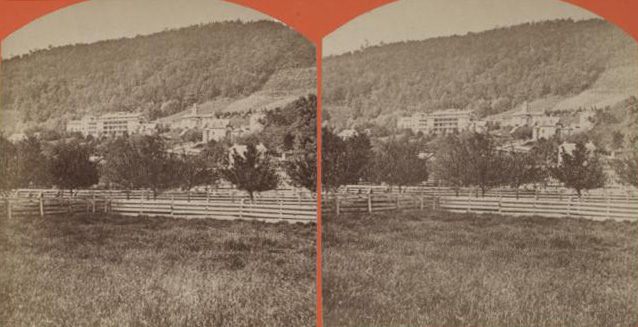

Our Home on the Hillside, Dansville, New York. (Photo: Yale University Art Gallery/Public Domain)

At Our Home on the Hillside, a 19th century sanitarium built in the tiny upstate hamlet of Dansville, New York, breakfast was at 8 a.m. It was the only meal James Caleb Jackson, the head of Our Home, ate each day. It always included fruit but rarely vegetables, except in spring when he ate stalks of asparagus every day. He mostly ate breads and porridges, and above all other foods he worshipped flour made from wheat ground whole.

For Jackson and his patients, “a desperate set” of people who had exhausted hope in mainstream medical care, meals were ideological affairs. Once a professional abolitionist who made his living speaking and writing against slavery, Jackson had turned to health reform after his own health broke down. He had a vision: He could cure people without using medicine.

Even as he became famous, a 19th century celebrity doctor, Jackson liked to emphasize how radical this idea was. He often called himself “unpopular,” but it’s more fair to say that he was a luminary in a progressive, fringy subculture that was as obsessed with consuming gluten as today’s food faddists are with avoiding it. “Of all the substances which I have ever used as food, I have never found another so good…as white winter wheat,” he wrote.

When Jackson is mentioned at all today, it’s because he is credited with creating an entirely new way to eat wheat—as a cold breakfast cereal named Granula, invented in 1863. It was the very first version of the fibrous flakes, krispies, and pads of shredded wheat that have defined American breakfast for more than a century.

John Harvey Kellogg, the inventor of Corn Flakes and the progenitor of Kellogg-branded cereal, might be the most famous cereal creator in America, but he got the idea directly from Jackson. Follow cereal’s evolution backwards, and you end up at in Dansville, New York, with Jackson, at Our Home on the Hillside.

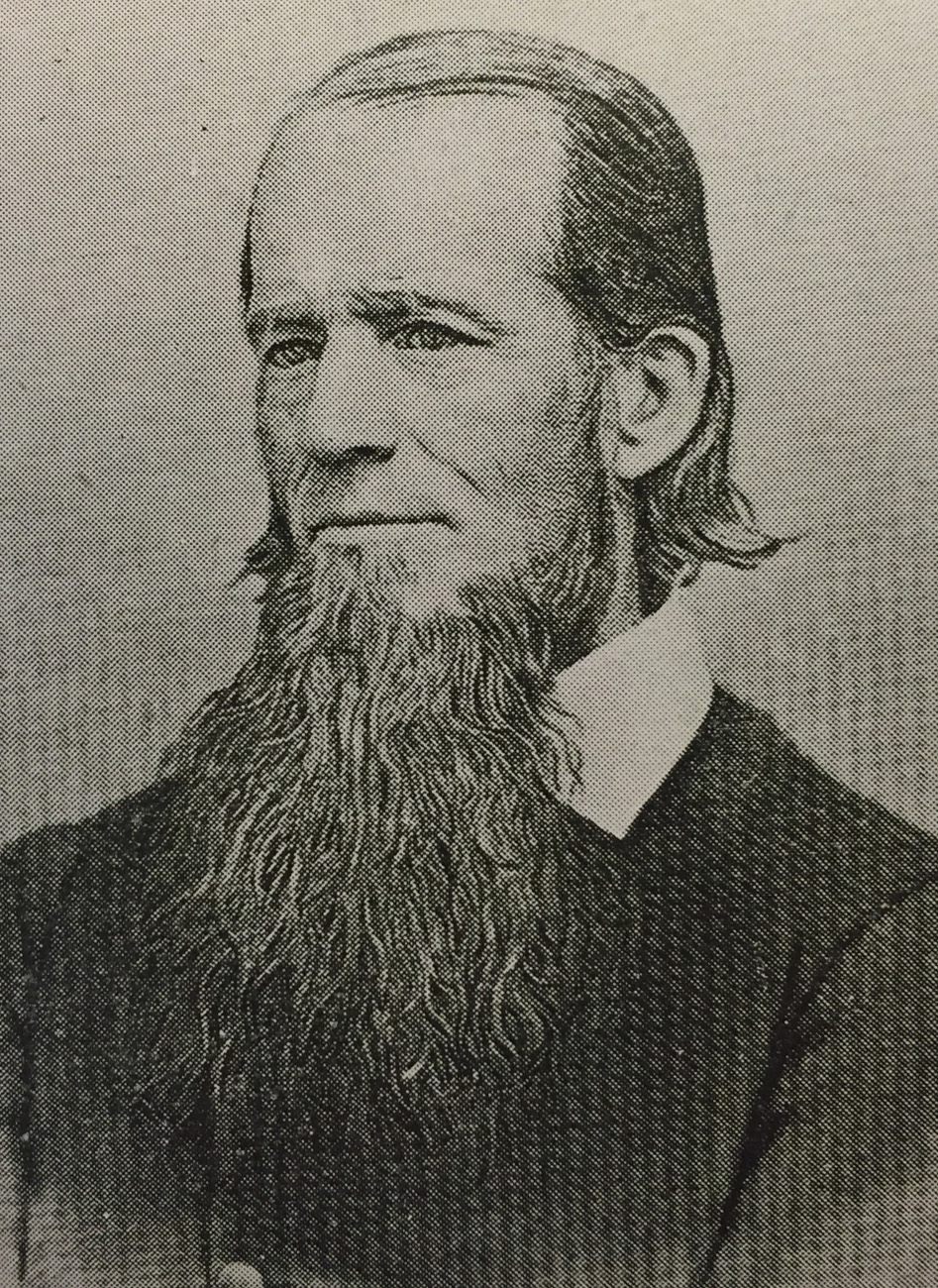

James Caleb Jackson in 1854. (Photo: Public Domain)

Usually, this is told as a story of intellectual property theft. Both Jackson and Kellogg were part of a 19th century health revolution that changed how Americans ate, but Jackson was the forerunner. Kellogg’s first cereal was almost exactly identical to the cereal Our Home served—the main distinction was that Kellogg changed the “u” to an “o” and called his concoction “Granola”. Often, accounts of cereal’s invention say that after Kellogg stole the idea of cereal from Jackson, all Jackson could do was sue him to keep him from using the actual name Granula.

The difference between that one letter turned out to be a $30 billion industry.

But the story of why Kellogg became a household name, with the fortune to back it up, is more complicated than one entrepreneurial health reformer stealing another’s idea. Jackson never truly understood the value of cereal. While he and his family recognized, celebrated, and monetized other innovations from Our Home, it took them more than a decade after Granula’s invention to start advertising it for sale.

The more I looked into Granula’s origin story, the more I became convinced that this blind spot had to do with an overlooked history—that Jackson had not invented Granula, to begin with, and that cereal’s true inventor was neither Jackson nor Kellogg but an uncredited woman.

A stereoscopic view of “Our Home” in Dansville, New York. (Photo: New York Public Library/Public Domain)

I had imagined that reaching Our Home would have required a trek up a winding road, but it’s less than a mile from the center of Dansville and the climb is not daunting. In this part of upstate New York, the land is waved into short hills, one following another, in slopes steep enough to feel like roller coaster drops but tame enough that winding mountain roads are rare. Jackson started Our Home here because there was a building available, but perhaps he was attracted, too, by the aura of this region, once called the burned-over district, for the religious revivals that flamed here through in the first half of the 19th century.

When the Jacksons lived on this hill, the slope was groomed into gardens, vineyards and vegetable patches, but now the grounds are overgrown and guarded with cameras. Dangers include poison ivy, worn-down buildings and cops that will arrest trespassers. The property is owned by the Buffalo-based developer Peter Krog, but to fix the buildings up—even to tear them down—would at this point be expensive enough that they’ve been left to stand as they are. I was given special permission to walk the grounds without risking arrest.

Follow a lawnmower-cut path through the forest, long grown back, and not far in, the route passes a once-white cottage, with a porch that would have looked down over the town. The central, red-brick building now has a tree growing out of one window. It was built to resist fire. The big white house that Jackson found when he first arrived, with its stately front of windows and walkways, burned down just before he retired.

The abandoned ruins of one of Dansville’s cottages. (Photo: Sarah Laskow)

Even without the trees, it would have been quiet here. Dansville stays cool in the summer, and when Jackson ran this place, he would have his patients lay for hours out on lawn blankets, with cushions under their heads and parasols keeping the heat off their faces. “The light of the sun falls on the slope soon after the sun rises; and if the day be clear, there is but little shadow,” he wrote. “To have from 75 to 125 person lying down on the beautiful green slope thus exposed to the sun is a sight worth seeing.”

If Jackson were running the equivalent of Our Home today, imagine that he might have created a retreat center with anti-racism lectures in the evening, that didn’t recognize gender binaries and served only vegan food. From his teens, immersed in the radical politics of his time, he had spoken out in favor of temperance, and in his 20s, he became involved with the New York State Anti-Slavery Society, as an agent and lecturer. He was 35 and running an abolitionist newspaper when his health broke down and he had to sell his share. He emerged from convalescence a convert to the water cure and went into the business, by opening his first health spa, a predecessor to Our Home, in Glen Haven, N.Y

This career change, from abolitionism to holistic medicine, was not a dramatic leap. In the antebellum North, water curists believed that bad health was tied up in immorality and poor diet; abolitionists argued for vegetarianism; and vegetarians believed in ending slavery and that abstaining from meat could help. “They saw meat consumption as being at the heart of an immoral and cruel society,” says historian Adam Shprintzen, who wrote The Vegetarian Crusade. “If you’re blind to the effects of eating meat, you’re blind to the slave system.”

To launch his Glen Haven water cure, where illness was treated with series of baths, Jackson and a friend concocted an ambitious event, a festival for 150 guests—former colleagues of Jackson’s, well-known abolitionists, the feminists Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Amelia Bloomer, and many newspaper editors. The main event was the “hygienic dinner,” in which there would be no salt, no spices, no tea, coffee, or wine, and no butter or lard. Instead, there were piles of fruits and boiled custards, baked rice, asparagus, potatoes, pies of apple, pumpkin, cheese, and blackberry, fresh figs, and for the carnivores, fresh trout and plainly prepared meat—”a feast,” one editor wrote, “which the incomparable skill of Mrs. Jackson has provided.”

Mrs. Jackson, according to her husband, had been skeptical of his career change. She had married him when he was 19 and a farmer and, while he was traveling to lecture on slavery, she had run their house as a stop on the Underground Railroad. She had “very great confidence in my editorial and oratorical abilities,” her husband wrote in a private, unpublished account of his life, but “very little confidence in my ability to carry on” a water cure. He had only recently trained as a doctor, and his belief that he could cure people without medicine frightened her. Still, Jackson wrote, she followed him from their old life to this new one.

“If you can find Mrs. Jackson,” wrote one guest after Glen Haven’s second annual hygienic feast, “you will see the quiet mainspring which puts all these men and women you see moving about the table in clock-like motion.”

That Lucretia was not called to health reform, as he was, bothered Jackson. She was “true to him personally,” he wrote in his autobiography, but “in truth, she had no inspirations.” She could convince herself of an idea by reading and reflecting, but “she had had no such convincement as had come over me.” He wanted an assistant and, in particular, a woman. When he found her, he wrote, their meeting was, with the exception of his revelation about health without medicine, “more influential upon me than any other single event in my life.”

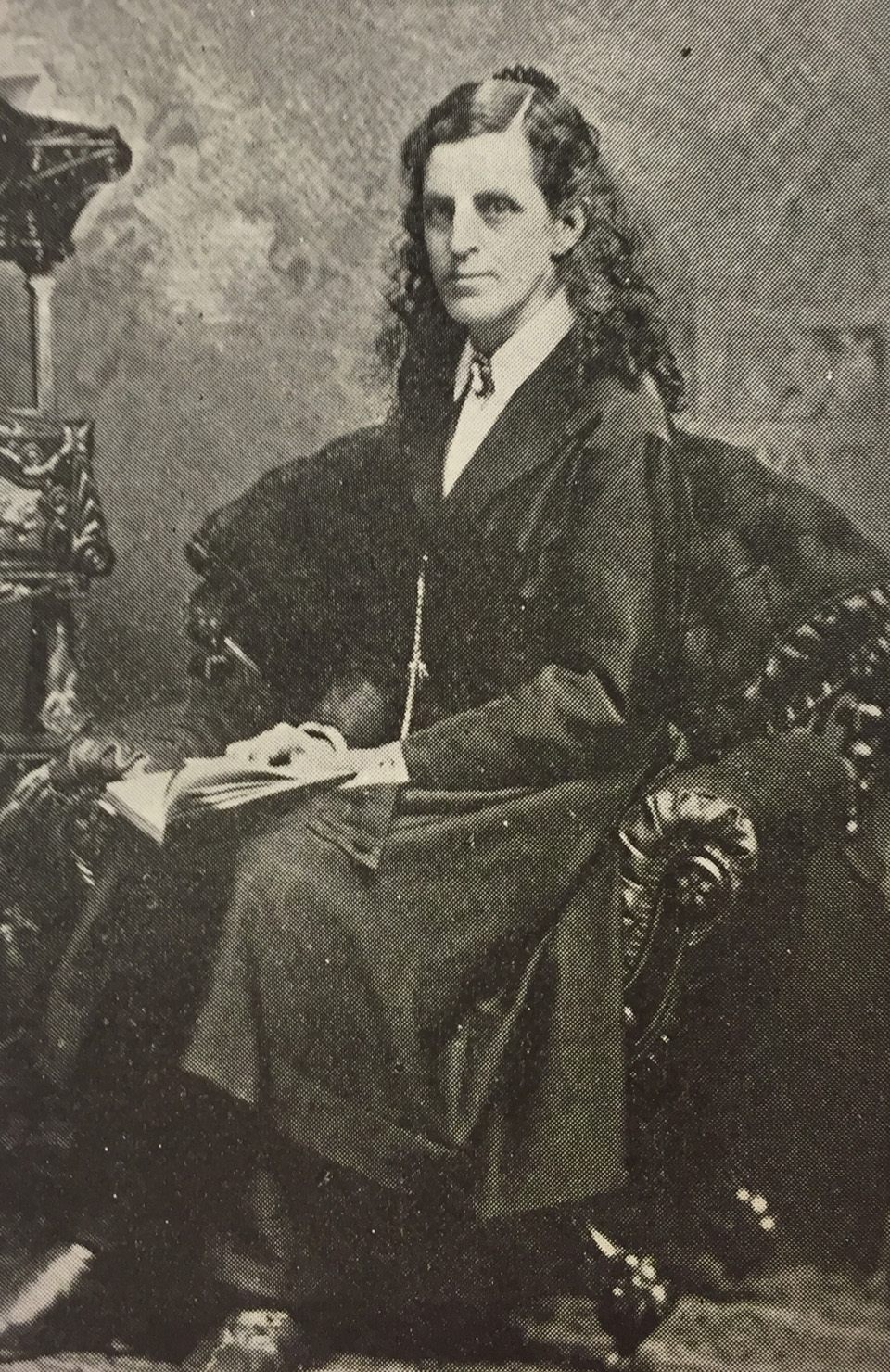

Lucretia Jackson. (Photo: Public Domain)

Harriet N. Austin came into Jackson’s life via letter. It was postmarked Owasco, one Finger Lake over from Glen Haven. She wrote that she was a physician at a water cure and had a very serious case. She needed help, and as Jackson made it a rule to help anyone, if he could, he traveled to see her.

Austin’s appeal to Jackson was not romantic—it was in her medical skill. When he reached Owasco, a journey of a couple hours, he found her care of her problem patient excellent, and the only difficulty the interference of others. Within a week, though, she had written him again. Someone in the village was saying that Jackson had found her incompetent, and she wanted him to deny that, in writing.

He did, but he couldn’t help adding more advice. He worried, he wrote, that she should not be setting up her own water cure, because “no one believed in a woman’s competency to get beyond the sphere of the nurse.” He believed in her, though. He wanted her to come work with him, and head the care of female patients. This was his proposal: he would pay her very badly for one year, but if the relationship worked out, she would have an equal share in the business. Whether because his was already well-known or because her experience in Owasco had shaken her, she came.

The masthead for the 1854 magazine The Water-Cure Journal, which included reports of cases treated at Glen Haven Water Cure. (Photo: Internet Archive/Public Domain)

In Austin, Jackson found the intellectual empathy he felt Lucretia lacked, as well as a surge in business, from women who wanted a “lady physician” to treat them. It was an easy sell. In the 1850s, male doctors tended to treat any problem a women had as a problem with her reproductive system; somehow it had become a trend to treat women by sponging caustic silver nitrate along the walls of the vagina. Austin and Jackson, by contrast, gave them chewy wheat breads, baths, and naps.

That first year of badly paid work was a good investment for Austin. She would stay with Jackson for the rest of her life. Not only did he make her a partner in the business, but soon after she came to live with them, he and Lucretia adopted her as a daughter.

If Jackson saw Lucretia as a helpmate, Austin he treated as an inspiration and intellectual equal; together, he wrote, they “regarded our fellows as dwelling on a very low plane, and determined to do the best we could for their enlightenment.” When they started a newsletter, Austin became the editor. When Jackson wrote his greatest treatise, “How to Treat the Sick Without Medicine,” he dedicated it to her: “My beloved daughter and friend…To you more than to any other person I am indebted for the health and strength whereby I have been able to write.”

Harriet N Austin. (Photo: Public Domain)

It was somewhere in this time period, before the Jackson family left their first water cure at Glen Haven, that the first experiments with Granula were supposed to have started. In one account, Jackson brings the recipe with him from Glen Haven to Dansville, when the family moves in 1858, after a fire and a bad business deal.

They were traveling about as far away as they could get from Glen Haven while staying in New York’s Finger Lake region: they moved from the southern end of Skeneateles Lake, the Finger Lake second furthest the east, to Dansville, just south of Conesus Lake, the westernmost of all 11 Finger Lakes. It took all day to make the journey, by buggy and train, and when they arrived, they found “an immense, castle-like building, with light in some of the windows.” In many ways, it was in bad shape, but, Austin wrote, “The Doctor laughed one of those pathetic laughs which up when the deep water of his heart is stirred at the found…we were a united family again, and in our own home.”

Glen Haven had been a success, but it was in Dansville that James Caleb Jackson’s fame was solidified. By 1866, Our Home had become the largest health institution of its kind in the country, “and I might perhaps add, the best in the world,” a Boston Post reporter wrote after a visit. Jackson, with his long, thick beard, his endless energy, and his passion for progress, was one of those people who can make others feel that they are important and their work special. He had what Virginia Woolf calls “a splendid mind,” with the ability to run further into the depths of human thought than all but a very people. Or, as the Post reporter put it, he was “not a man in a thousands, as we say—but only one in very many thousand.”

In the years after Civil War, Our Home became an oasis for the progressive movement, triumphant in its defeat of slavery, but still striving to reform American life. Frederick Douglass delivered lectures at the sanitarium; Clara Barton came for treatment. She was so taken with Our Home that she stayed in Dansville and founded the Red Cross there. After the war, most women still wore dresses puffed out with underskirts and bustles, the top tight at the waist, neck and shoulders, but at Our Home, many chose to wear the “American costume” that Austin designed—a pair of slim but loose pants worn under a dress with a loose waist, loose shoulders, and the skirt cut short.

A doll made by Lucretia Jackson in the 1870s, wearing the “American costume,” at the Dansville Area Historical Society Museum Collection. (Photo: Sarah Laskow)

Jackson and Austin were both fanatical about this costume. On her first trip to Dansville, Austin wore it to the hardware store to buy fifty yards of carpet, causing the owner to sprint to his friend’s office to share what he had seen: “a woman dressed like a man, who does business just like a man!” The American costume was similar in design to the more-famous Bloomers, but Jackson insisted that the American costume was “as nearly like what is commonly known as the Bloomer costume, as an elephant is like a rhinoceros.” With its loose waist and top, Austin’s outfit was designed to release any restrictions on a woman’s inner workings and promote health. When he first saw her wearing it, Jackson wrote, “I actually cried for joy.”

If Our Home was a utopia of sorts, it was also a business. Jackson and Austin developed a following, and much of their public work was dedicated to fanning the coals of this small cult of personality. Starting in the late 1850s, Our Home sold lithographs of Dr. Jackson and Dr. Austin, that patients could order by mail, and later added one of Our Home itself. Austin and Jackson started publishing a paid newsletter, the Laws of Life, which advertised hand-grist mills for those who wanted to grind their flour just as it was ground at the sanitarium and special bread pans that would allow them to make proper wheat bread. Jackson churned out books, five in the first five years of the early 1870s, and Our Home sold those, too, as well as patterns that would allow women to make their own American costumes. But it seems that they did not start selling Granula until 1876, more than a decade after Jackson was supposed to have invented it.

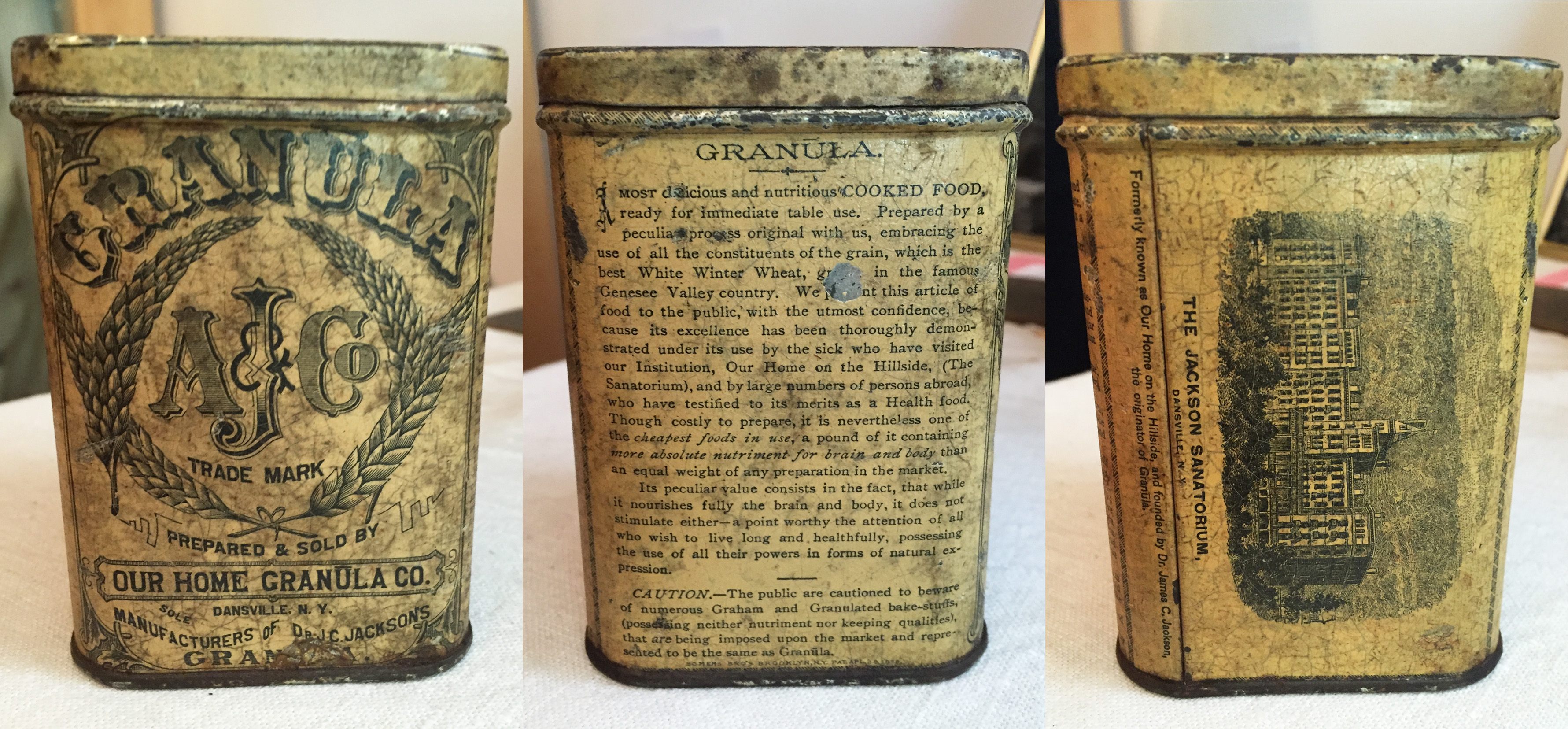

An existing jar of Granula, at the Dansville Area Historical Society. (Photo: Sarah Laskow)

Copies of The Laws of Life are hard to come by these days, and I wasn’t able to find a full set. But in 1858-9, 1866, 1868-9, 1873, and 1874, there’s no mention of Granula, while pages and pages are dedicated to the American costume. The newsletters even include recipes, by Lucretia, for hard biscuits, soft biscuits, and other foods served at Our Home. But the earliest mention of Granula—originally Granūla—I could find was published in 1876, in a full-page advertisement, larger than most Laws of Life ads.

When they did start advertising Granula, the proprietors of Our Home boasted that it might be “the best food known to man” and had been subjected to testing and modification over many years. But the ad copy, a bit defensive, also recognizes that Granūla has been absent in the pages of the journal: “We have never before said anything about it publicly because it is our plan, before we may say anything to the public in regard to any plan or method of ours for treating the sick, to test it so thoroughly that when we do make a public notification we are certain that we shall not have to withdraw or qualify our statement.”

Already, this is strange. No one associated with Our Home ever seemed shy about sharing their ideas, with great verbosity and conviction. It may have been impossible for Dr. Jackson to test everything he said in regard to treating the sick that thorough, because he said quite a lot, and because he worked as much by inspiration and instinct as by scientific method.

The main entrance and lobby at Our Home, Dansville. (Photo: Public Domain)

The most suspicious part of the “we didn’t want to say anything yet” story, though, is that they did publicly describe the cereal. They just didn’t use its name.

The formula for Granula is simple enough. Start by making wheat bread: mix flour and water into a dough, roll it into ¾ inch cakes, and bake. Then break those cakes up, and bake again. Take the rock-hard crackers that result, and run them through a grinder. The result is often compared to pebbly Grape-Nuts. (When I tried making my own batch, I found it even more unappealing than that—after I added milk, it became mortar-like and somehow both dry and chewy at once.)

A recipe resembling this one appeared in the Laws of Life as early as 1869, years before the word Granula appeared in its pages. Answering a question about what form of wheat bread will keep longest and be healthy, Austin describes exactly the same process as making Granula, only she calls it “rusk.” It’s made from wheat biscuits, split in two, dried in an oven, broken up fine and ground in a hand mill. “When this rusk is to be used,” she advises, “it should be made entirely soft by soaking either in milk or warm water.”

Even before that, though, Lucretia Jackson published a recipe for “rusk” in her 1867 cookbook:

“The various kinds of bread described above, when broken, or so old as to be dry, are excellent made into rusk. Dry them thoroughly in an oven, break in a mortar and grind coarsely in a coffee or hand mill. Eat in milk after soaking a little while, or soak in hot water a few minutes, and eat with milk gravy, cream or a little sugar.”

That sounds like cereal to me.

Cottages at Our Home, c. 1860s. (Photo: New York Public Library/Public Domain)

In the pages of the Laws of Life, Lucretia Jackson is a beloved figure, sometimes called Mother Jackson, a warm presence in the background of all life at the sanitarium. She and Austin seemed to have a good relationship, as the two most important women in Dr. Jackson’s life: in one photo of the entire, large family and their associates, Lucretia sits just before Jackson, while Austin stands just behind him. But it’s also clear that, as that correspondent noticed in 1851, back in Glen Haven, Lucretia is the “mainspring” who keeps the practical aspects of the operation moving. She was Our Home’s chief matron, and while she might have been guided by Jackson’s pro-wheat agenda, for many years she was in charge of making sure people were fed.

To Our Home’s credit, the ad copy for Granula never says that Jackson invented the stuff, only that “it has been many years since Dr. Jackson first introduced it to use on his table.” As interested as Jackson was in talking and writing about food, he never showed much interest in preparing it (although he does mention once that at Glen Haven he would help his wife in the kitchen—while he was also helping with the washing, helping the carpenters, currying the horses, and driving to get the raw materials of breakfast).

Perhaps James Caleb Jackson did invent breakfast cereal, but it’s hard to believe that if he had, he wouldn’t have regarded it as a great accomplishment and written about it extensively. So many other details of the radical way of life practiced at Our Home were celebrated ad nauseum in the newsletter, by both the staff and patients, that it seems most likely that no one thought about this invention as anything special. Patients wrote paeans to the dense wheat bread served at the sanitarium, but no one mentioned missing rusk.

A wheat biscuit from the 1860s, now at the Dansville Area Historical Society. (Photo: Sarah Laskow)

What changed in 1876? There were two forces that might have pushed Our Home to start selling rusk as Granula: competition from without and a change of management within. That was the year Kellogg became superintendent at the Battle Creek Sanitarium, and around the time he started his own experiments with cereal. On his menus, he listed “granula”, but by 1877, he had created a cereal of his own, which improved upon Our Home’s by adding a note of sweetness and more grains. Accounts of Kellogg’s start in cereals often say that Jackson sued or threatened to sue him over the use of the name Granula, but the scholars who have looked into this most closely haven’t found enough evidence back that up, and usually say Kellogg began selling his cereal as “granola” simply to avoid any legal conflict.

In fact, around this time, Kellogg’s relationship with Our Home seems friendly enough. In 1878, he invited Dr. James H. Jackson, James C.’s son, and his wife, Dr. Kate Jackson, to the opening of the main Battle Creek building. The younger Dr. Jackson declined, but he wrote to Kellogg, “It is a pleasure to us to feel that there are persons of near our own age and education who are working along the same line as ourselves…You with your fine Institution and your paper, stand in the foremost rank, and I assure you we are glad for it.”

A 1894 advertisement for Kellogg’s. (Photo: Internet Archive/Public Domain)

James H. Jackson was also changing Our Home in 1876. He had long been involved in the business of the sanitarium, but that year, having just graduated from medical school, he was beginning to take over management of institution. Three years later, in 1879, James C. Jackson would step back from daily operations altogether, and James H. Jackson would step into his place.

This management transition from one generation to another would have changed, in some ways, the way Our Home was run. The older Dr. Jackson, says Shprintzen, the historian, was a “transitional figure” in the 19th century’s food movement. As Shprintzen writes in his book, earlier in 1800s, the ideology of vegetarianism and food reform “manifested itself by connecting dietary choices with other social and political reform causes.” But by the turn of the century the movement had become more commercialized, and “marketed healthy fare…promoted normative cultural values.” James C. Jackson bridged those two modes—he was soaked in ideology, but pragmatically capitalist, as well.

Perhaps, though, it took James H. Jackson, as a member of the next generation, to fully realize the commercial potential of the Our Home brand—and the value of his mother’s innovation. Since the earliest recipe that resembles Granula belongs in the book that’s bylined by Lucretia, I think it’s most likely that credit for its invention should go to her.

To make Granula from scratch is to appreciate the arc of invention. After following the first step of Lucretia’s recipe, making a simple wheat bread, the dense lump I had tasted good enough—chewy, but not unpleasant. The second-step, twice-baking, seems like overkill now but would have been routine at the time: Melba toast is a twice-baked bread, and so are croutons.

But when I made it with this bread, the chunks that came out of the oven were tooth-breakingly hard. The bit I did managed to eat tasted good, though, even familiar. It tasted like bran flakes.

I can see one of the Jacksons looking at that stone bread and thinking: why not try grinding it? The result, if my experiment was any indication, would have been sandy and impossible to chew, and she would have taken the next obvious step. She would have poured milk over her pile of wheat pebbles, waited a few minutes for the cereal to soften, and taken a bite.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook