The Historically Hazy Story of Donora’s Deadly Smog

A 1948 environmental disaster in the Pennsylvania town resulted in half truths, conspiracy theories, and the introduction of clean air laws.

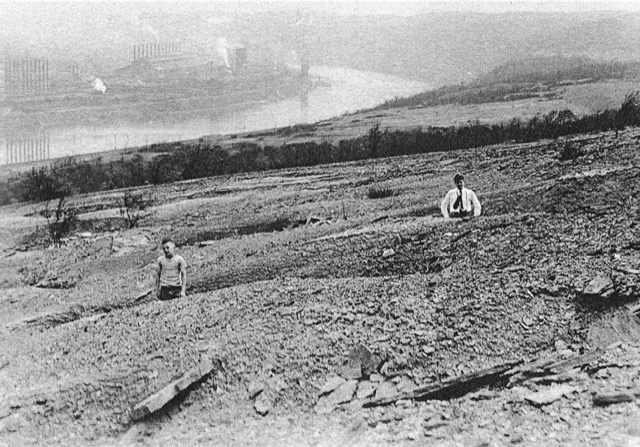

The residents of Donora, Pennsylvania, knew their riverside factories were dirty long before 1948. They could tell which sector of the American Steel and Wire complex was producing the bulk of the day’s pollution from the air’s tint—the open hearth produced reddish-brown exhaust, the blast furnace’s was black, and the zinc works, possibly the worst of them, emitted a noxious yellow smoke, a result of the sulfur dioxide with which it was laced.

Pollution was one thing, but American Steel and Wire employees faced even more acute dangers. Workers often “retired” by age 30. Local historian David Lonich’s father, a crane operator in the zinc works, lost his sense of smell when a chain hit him across the face. A more common condition was “zinc jitters,” which was treated with a concoction of water, ice, milk, oatmeal, and whiskey—the water and ice for hydration, the milk and oatmeal to leech the metal from their bodies, and according to Brian Charlton, who runs the Donora Historical Society and the Donora Smog Museum, the whiskey so they’d actually drink the stuff.

This day-to-day pollution alone would make the town an unlikely epicenter for a burgeoning environmental movement. But after Donora became the site of a fog that would kill dozens and sicken thousands more—one of the worst environmental disasters in the history of the United States—the town’s very name became a recognized shorthand for the dangers of unregulated industry and the need for federal clean air laws. First, though, the story of the disaster would be told and retold in a modern-seeming back-and-forth of misinterpretations and counternarratives. The Donora Smog became an ideological morass of subjective memory, the protective half-truths of insiders, the distortions of outsiders, conspiracy theories, and the obfuscating legalese of those responsible, all competing for the right to tell what really happened in the fog.

Tales of gruesome Donora hazards went back decades before the event. One story goes that in 1919, a 22-year-old World War I veteran named Andrew Posey was working as a ladle checker on the blast furnace when 60 tons of molten iron was dropped on him, incinerating him within seconds. American Steel and Wire erected a memorial on the property, and supposedly interred the whole block of metal in place of a body. Some claim that the ore was dug up during the material shortages in World War II. Not everyone in town believes this story. The memorial itself is still there.

Still, many older Donorans remember the mills for the thriving, diverse community that the factories supported. “It was a dirty town,” Donora resident Charles Stacey says, “but it was a prosperous town.” That began to change on Wednesday, October 27, 1948, when an unusual temperature inversion moved across the Monongahela Valley. In a temperature inversion, a cold air front acts as a cap, preventing warm air—and, in this case, the exhaust from the factories—from rising. By late morning, by which time the smog had usually burned off, a stagnant haze of pollution from the zinc works still filled the valley. Streetlamps stayed lit at midday. A senior in high school at the time, Stacey remembers having to be extra cautious walking home because he couldn’t see his feet to gauge where the sidewalk became the curb.

Many Donorans still carried on over the next few days as if the smog was of a piece with the town’s usual pollution, even while they held handkerchiefs over their faces and emergency responders carried 60-pound oxygen tanks door-to-door to treat elderly residents and asthmatics. “A Banner Event In Spite of Weather,” Donora’s Herald-American claimed of the local Halloween parade, directly below a headline about smog-related deaths, adding, “Participants Have Merry Time Vieing [sic] For Many Prizes.” Donora High’s Dragons (the nickname intended to evoke the town’s belching smokestacks) lost a football game, 27-7 to rival Monongahela. Charles Stacey says he didn’t know the extent of the disaster until he turned on Walter Winchell’s radio show and realized the nationally syndicated journalist was talking about his town.

The smog didn’t lift for one day, then two. By Saturday, when the town’s funeral homes were full, the Donora Hotel’s basement was put into service as a morgue. The smog still didn’t lift. The mill finally ceased operations on Sunday, by which time rain showers had broken the inversion and forced the smog to dissipate anyway. David Lonich says his father described the fog as rising “like a curtain” and revealing a line of boats backed up on the river, waiting to deliver their loads to the mills. Officially, the zinc works shut down for the next two weeks, but Lonich says his father was back at work on Monday, which would mean that the mill was idle for less than a day. An estimated 4,000 of the town’s 14,000 residents were sickened with respiratory difficulty, headaches, vomiting, and stomach pains. The number of fatalities is still in dispute. “They stopped counting on Sunday,” Lonich says.

The specifics of the Donora incident are similar to a few roughly contemporaneous disasters—Liege, Belgium had a similar fatal air inversion in the 1930s, and the Great Smog of London would kill over 4,000 and sicken 100,000 more in 1952. But what differentiates Donora is that it marks a turning point in the then-fledgling environmental movement, and one that centers on an odd paradoxical conflict: how do you tell the story of a fog after it lifts?

Lots of publications tried. Within a week, the event was headline news in national publications from The New York Times to Life, in articles that led with horrific, visceral descriptions of the fog. A New Yorker article by Berton Roueché recounted the route of Dr. Ralph Koehler through 24 hours of house calls to patients who couldn’t breathe, often too late to save them. A consensus, based on all available evidence and common sense, quickly formed that pollution was to blame: “19 Die Here As Result of Killer Smog,” blared a November 1 headline in Donora’s Herald-American.

As a recent Quartz article points out, there were no national laws at the time regulating air pollution, but The Pittsburgh Press was already using Donora as an example of how the city’s recently enacted smoke control laws, which mandated the industrial use of fuels that burned cleaner than bituminous coal, had “proved its worth.” American Steel and Wire tried to minimize its culpability, taking out a newspaper ad within a couple of weeks, extending their sympathy “with deep sincerity” to smog victims, while simultaneously denying culpability, noting that a representative from the U.S. Public Health Service claimed there was no evidence to “incriminate any one particular plant or mill in this area.”

Most Donorans, their livelihoods at stake and without illusions regarding the danger of their jobs, chose to go along with U.S. Steel’s narrative. Devra Davis, in When Smoke Ran Like Water, quotes a zinc worker and member of the Donora Borough Council telling a longtime opponent of the mill’s pollution from nearby Webster, “I’ve got a darn good job and I’m going to keep it. I don’t care what it kills.” Dave Lonich said his father joked about the dangers, saying that the zinc in his system was why he never got colds. “These were tough guys,” he says. “They came back from storming the beach at Normandy and at 21, 22 years old, went right into the mills to support their families.”

When a national Public Health Service commission was established in 1949, the Herald-American reported that none of 8,000 people surveyed by mid-December admitted on the record to having been treated for respiratory distress. Their level of caution was probably excessive—the commission, filled with researchers with industry ties, took soil and air samples, attempting, in a sense, to quantify the fog, then placed the blame entirely on the air inversion, calling the entire event “an act of God.”

With objective measures in dispute, conflicting accounts of the smog’s severity added a layer of unreliability to many first-person reports. Many accounts of the football game claimed that players couldn’t see the ball and that Donora’s Stanley Sawa was called home because his father, a mill worker, had died from respiratory distress, yet box scores show an unusually pass-happy game (Charles Stacey points out that the football field was situated high on a hill, above the line of the smog), and records show that Sawa’s father didn’t die until a few days later. The Pittsburgh Sun-Telegraph printed a photograph of a darkened Donora street, claiming it was taken at noon, while Brian Charlton points to statements by the fireman who had taken the photo, who said it was 7 or 8 at night. And many Donorans saw the national reaction as overwrought or demeaning. Add an exclamation point and headlines covering the smog start to read like B-movie poster copy, touting a “Killer Smog,” “Death Over Donora,” and a “Scene of Desolation.” At least one hatmaker began manufacturing “designer millinery smog masks.” The National Enquirer claimed 13,000 people had died.

In the end, the smog never had much direct effect on U.S. Steel’s bottom line, aside from a class-action lawsuit settled for $250,000, with no admission of responsibility for the fog or the deaths caused by it. As for Donora, for all its citizens’ efforts to keep the zinc works open, it closed in 1957. The reason wasn’t federal overregulation, it was because their horizontal retort furnace system was outdated and too costly to upgrade. The rest of the mills closed soon after. Some of the old buildings have been repurposed (perhaps most fittingly, one is a depot for Mid Mon Valley Transit Authority public buses, which run on compressed natural gas), but most of them are gone.

Recent census figures put Donora’s population at around 5,000 people, about a third of what it was at the time of the smog. A sign in the Smog Museum traces the lineage of the 1970 Clean Air Act, the strongest (and currently endangered) federal air pollution regulation ever enacted, back to the 1955 Air Pollution Control Act, which was passed in response to the Donora Smog. It reads, with equal parts pride and knowing irony, “Clean Air Started Here.”

This mild exaggeration is fitting for an event in which printed casualty tolls varied from as low as 11 deaths to as many as 60. The Donora Historical Society uses a total of 27, with the caveat that there’s no way of knowing how deaths from lingering respiratory illnesses over the years can be tied to the smog. But tragedies are about more than simply quantifying death totals, and this one, centered on a cloud, that archetypical symbol of ephemerality, maybe more than most. Many of the originally reported inaccuracies—the invisible football game, for example, or the day-for-night photo—are still repeated, as time solidifies the “print the legend” version of history.

As horrific as the facts were, it may have been those legends, from Berton Roueché’s evocative prose to the sensationalistic journalism of less reputable outlets, that captured imaginations and spurred legislative action. As ever, stories reflect the world the teller wants to see. To that point, David Lonich said that some older Donora residents, perhaps trying to salvage the town’s past reputation for prosperity, to this day consider the smog a non-event, or even a conspiracy akin to “the man on the moon.” Smog deniers claim that the weather that week was basically the same as usual, and that the deaths were nothing but a statistical blip, a mere coincidence.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook