Who Were the Warrior Women of Dahomey?

The only documented all-female army in history inspired the Dora Milaje.

In Atlas Obscura’s Q&A series She Was There, we talk to female scholars who are writing long-forgotten women back into history.

In Marvel Comics, Black Panther, of the fictional African nation of Wakanda, leads a group of warriors called the Dora Milaje. These women are elite fighters, both feared and admired for their training in martial arts and hand-to-hand combat—and they are inspired by a group of real women in history: the warriors of the Kingdom of Dahomey.

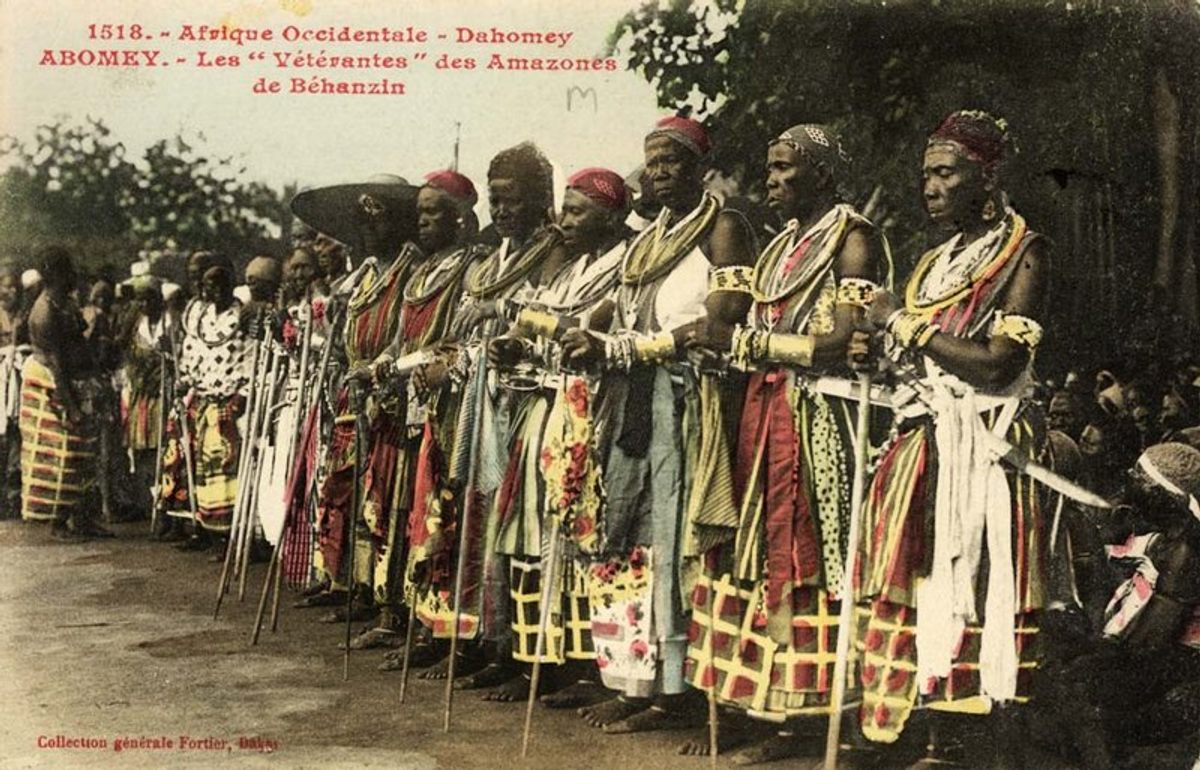

Hollywood loves these women warriors, who were known as the Agoji warriors or Mino in their own languages and were dubbed “Dahomey Amazons” by the French in the 18th century. The upcoming movie The Woman King, starring Viola Davis, is based on these warriors, the only documented all-female army in history.

As a graduate student, Lynne Ellsworth Larsen—now an art history professor at the University of Arkansas at Little Rock— began studying the Kingdom of Dahomey (circa 1600-1904), which was located within present-Benin and was a major player in the West African region for much of the 18th and 19th centuries. After coming across the book Wives of the Leopard by Edna Bay, Larsen became hooked on the gender politics of the Dahomey Kingdom. Her article “Wives and Warriors: The Royal Women of Dahomey as Representatives of the Kingdom” for The Routledge Companion to Black Women’s Cultural Histories, looks at the influence of Dahomey women beyond the borders of the kingdom.

The women of Dahomey played important roles in all aspects of kingdom life. Although the king had ultimate leadership, royal women made their mark in the world of politics, religion, and especially in the military. Atlas Obscura spoke with Larsen about the evolution of the women warriors of Dahomey, the ways in which they were portrayed in French media at the time, and what their legacy should be.

How did the women warriors of Dahomey come about as an army? You talk about several theories in your article.

So that’s debated, right? We’re not sure for certain. Some say it could be as early as King Houegbadja [who ruled circa 1645 until 1685], who was the first king to settle in Abomey, which was the capital of their kingdom. He had a core of elephant warriors, so we know women were armed and doing hunting at least by that point. Now after Houegbadja died, his son Akaba took the throne and ruled until he died circa 1716. When Akaba died, his twin sister took his seat. Scholars debate as to whether she was a true queen or simply a placeholder for Akaba’s heir, but either way, she was pretty much in charge of the kingdom. She would’ve needed a female guard to keep her safe within the palace. Visible, armed, female warriors may have been put in place at her time. Now, again, it’s contested because they may have been put in place before then.

There were other incidents where it looks like kings needed a larger army than they had to win certain battles so they had armed female warriors in the back. But it looks like it was during the reign of King Guezo [who ruled from 1818 until 1858] that the female warriors became a very clear, visible, famous part of their kingdom and feared by the neighbors. This was a slave-trading economy, so war became part of their yearly duties. You had farming season and you had war season and part of that was to expand and strengthen the kingdom and part of that was to collect humans for the slave trade. So, unfortunately, the female warriors were part of that heinous part of history.

Did you encounter any similar all-women armies around Africa at that time?

Not that I can think of. Women in West Africa can hold a lot of power. So for the Dahomey, we’re talking about the female warriors but there were also female court members to balance the male court. The queen mother in Dahomey was considered the “reign mate” of a king. I love the idea, though, of having Dora Milaje-type armies throughout the continent.

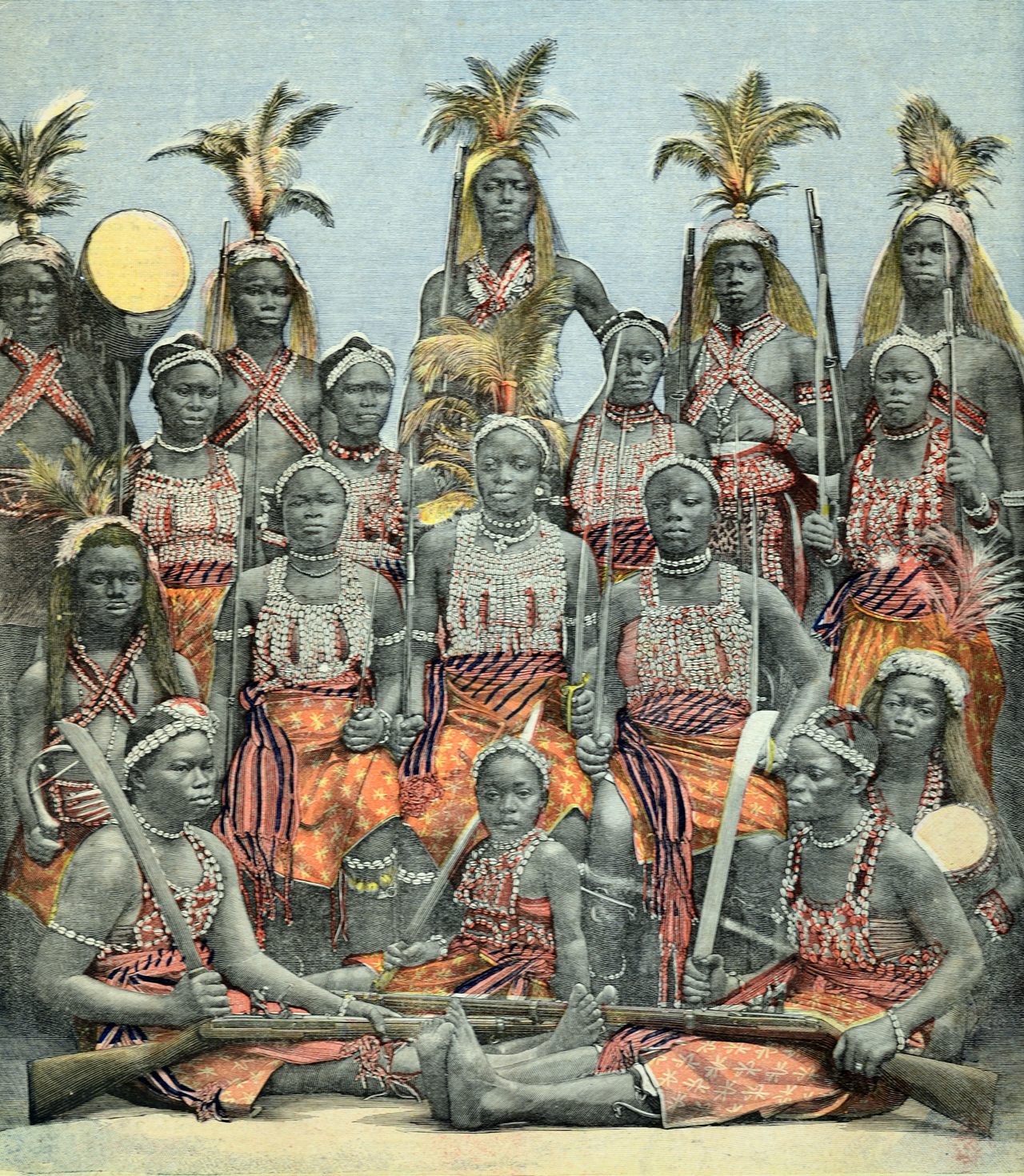

In 1890, the first Franco-Dahomean War began. What role did the women warriors of Dahomey play? What were the reactions like from the French side? How do you think that contributed to the way that they were portrayed in European media at the time?

So this is really interesting because the French had their mission in the Kingdom of Dahomey, right? Their civilizing mission. Part of their justification for exploiting the land and the people of these West African areas is that there were these women who took trophy heads back to the king as proof that they had taken lives. For the French, this was the height of barbarity and primitivism, and this became the call to that justification of colonization.

The French would have permanent exhibitions where they would have reenactments of battles that would take place, which is really interesting if you know that female warriors in Dahomey often performed reenactments for the king’s court. If the king had visitors come, ceremonies might be performed. It was also used as a form of entertainment. These women would come and do mock battles to show off their skills and to impress visitors. They’d climb over roofs and they would catch things on fire. According to colonial accounts, it was quite a spectacle to see.

So it was interesting to have the French do these reenactments for a very different purpose, the same way that collecting heads served a purpose for the Dahomean kings. Even during the Columbian Exposition in America [in 1893], they had big signs painted of Dahomey warriors holding a head.

What legacy does this all-female army leave behind? How does comparing the Dahomey to white, Greek, fantastical Amazons complicate the perception and reality of these real female African warriors?

I think that’s the crux of it. We don’t want to mythologize. The scholar in me embraces complexity. I love the idea of powerful, black women who had agency and were doing things that Europeans thought only men could do. I love the idea of breaking apart those hierarchies. However, I don’t want to gloss over and say that they weren’t also implicated in this horrible slave trade. I don’t think we should ignore that they were part of that system, part of a patriarchal system. Yes, they were powerful, but it was still the king that was making these decisions. In terms of legacy, I would celebrate representation and would celebrate strength and agency where it is, but I would also be wary of idealization and glossing over complexity.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook