Minnesota’s ‘Root Beer Lady’ Lived Alone in a Million-Acre Wilderness

The “loneliest woman in America” brewed root beer for thousands of visitors.

For paddlers in Minnesota’s million-acre-plus Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness, a panorama of lakes and trees stretches as far as the eye can see. Bald eagles, swans, and loons patrol the BWCAW’s waters, deer, bear, and the occasional moose ramble its woods, and its pristine lakes teem with walleye, northern pike, and bass. What you seldom see are other people.

Yet this is where Dorothy Molter lived from 1934 to 1986. On the Isle of Pines in Knife Lake, 15 miles by canoe from the nearest road and 30 miles from the town of Ely, she operated a fishing camp in the summer and lived in icy Northwoods solitude in the winter. But while Molter became legendary for her rugged and independent life, it was the root beer she brewed with lake water and served to thirsty paddlers that cemented her fame as “the root beer lady.”

Originally from Chicago, Molter fell in love with the Northwoods in 1930 during a family fishing trip. Though trained as a nurse, she found few jobs available during the Depression in the city. So she returned to the Isle of Pines, where Bill Berglund, 30 years her senior, promised that if she stayed to help run his fishing camp, he would leave her the four-cabin resort at his death. When he died in 1948, 41-year-old Molter took over.

She gained a reputation among Elyites as a wilderness “first responder,” patching up injured canoers and animals alike. She removed fishhooks from body parts, splinted broken bones, and kept a boy struck by lightning alive until a rescue plane arrived, earning her the nickname “Nightingale of the Northwoods.”

Yet it was her solitary life that interested people the most, notes Jess Edberg, executive director of the Dorothy Molter Museum. “An unmarried woman living alone in the wilderness was a curiosity,” she says. Molter herself once swore that she’d only marry a man who could “portage heavier loads, chop more wood, or catch more fish” than she could.

Molter needed such skills. Without electricity, telephone or running water, she chopped wood, hauled lake water, and harvested ice in winter to preserve food in warmer months. Communication— by mail, telegraph or word-of-mouth—often took days. The challenges increased as Molter’s island life tangled with the U.S. government’s efforts to preserve the pristine wilderness surrounding her home. After float plane flights to the island ended in 1952, Molter’s suddenly even-more-isolated life gained national attention. A Saturday Evening Post article dubbed her “the loneliest woman in America.”

Later, the Wilderness Act of 1964 mandated that residences, buildings, and businesses had to be removed from the area. Molter received and ignored repeated orders from the U.S. Forest Service to vacate her camp. Her battle of wills with the Forest Service brought Molter even more attention. Eventually, with support from the public, politicians, and environmentalists, she prevailed. Though forced to close her fishing camp, Molter could stay on the Isle of Pines as a “volunteer-in-service,” making her the last resident of the Boundary Waters.

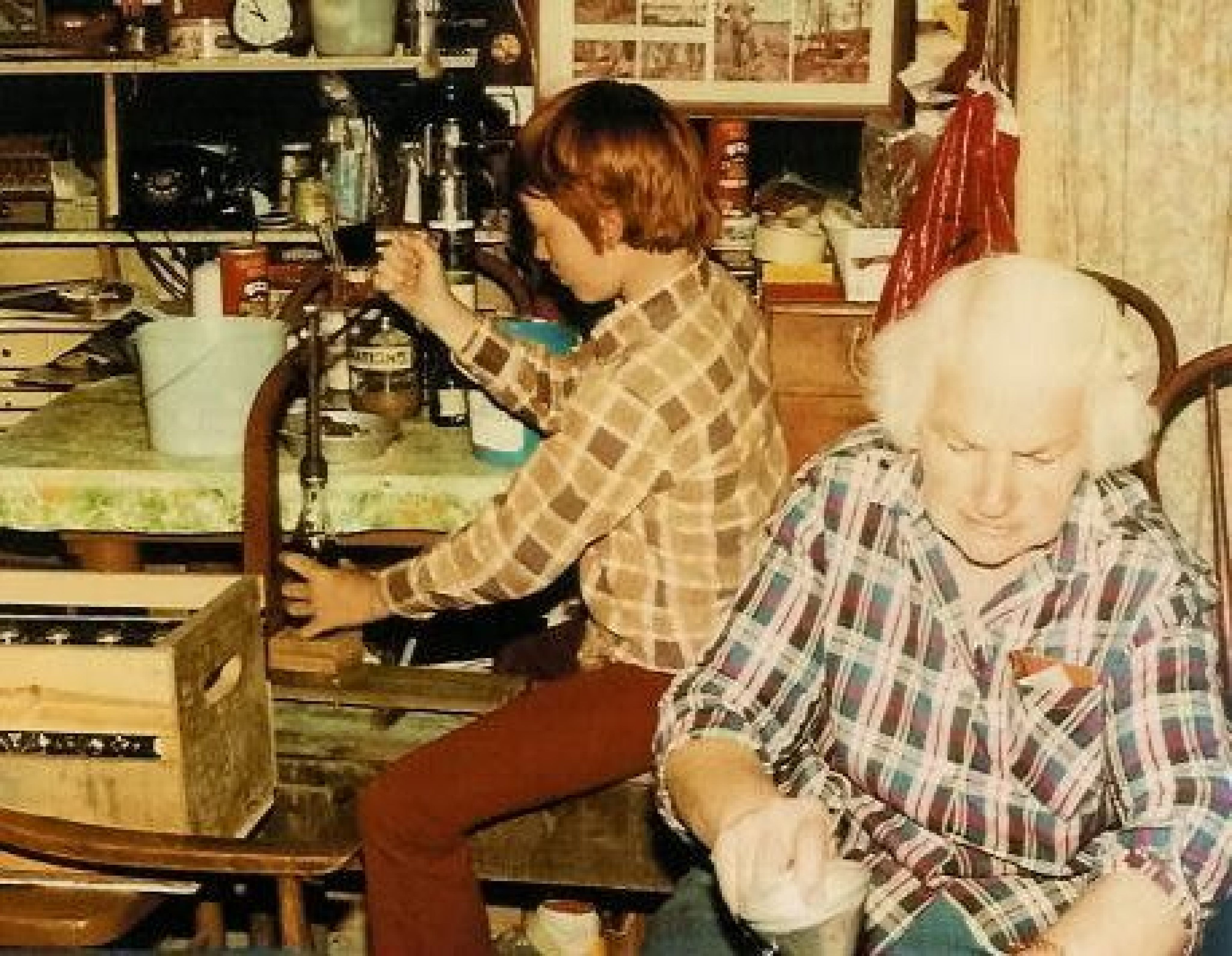

But she was hardly lonely. When plane flights ended, it became impossible to haul in the heavy bottled drinks that she had provided to thirsty paddlers. Undeterred, Molter began making her own root beer. She purchased flavoring syrup from the Ely A&W and the local Boy Scout base, blending it with sugar, yeast for carbonation, and lake water in an eight-gallon crock. (Her recipe jokingly suggests stirring it with a canoe paddle for added pine flavor.) She bottled the root beer in hundreds of empty glass pop bottles she had accumulated over the years, since there was nowhere to dispose of them. Friends and relatives often came to the island to help her brew and bottle, and, says Edberg, they even came for “ice-cutting parties in winter, to stock her ice shed.” Because she was no longer allowed to legally operate a business within the BWCAW, she offered her root beer to visitors in return for a small donation.

Reportedly, the quality of the drink wasn’t always consistent. But that didn’t stop as many as 7,000 thirsty and curious canoeists who pulled ashore every summer to visit the white-haired root beer lady and slug down around 12,000 bottles of the homemade brew that she chilled with the winter’s lake ice. According to Butch Diesslin, a Molter Museum board member, the local Boy Scouts were particular fans. Though they were intrigued by a woman living alone in the wilderness, “they were also curious about root beer made from lake water,” he says. “Anything sweet was a treat.”

Even as she aged, Molter refused to entertain the thought of leaving her island home. Though she occasionally visited family in Chicago during the winter, mostly, she stayed in her camp on Knife Lake, despite the brutal cold. “I like the winter the best, even though the thermometer here has fallen as low as 57 degrees below zero,” she once mused. “I never tire of tramping across the frozen lakes or through the deep silence of the forest in winter.”

Molter’s lifestyle gained her many admirers. “Work hard, be nice, have integrity, know what you’re doing is good despite rumors and criticism—I find that inspiring,” says Edberg. After Molter passed away at her cabin in 1986, a group calling itself “Dorothy’s Angels” hatched a plan to move her buildings to Ely and create a museum in her honor. They enlisted help from the Ely-based Voyageur Outward Bound School and the Boy Scouts to travel by dogsled over the winter ice to the Isle of Pines. There, they dismantled and transported each building back over the ice to Ely. At the last minute, an early thaw made travel too difficult for dog sleds, but the Forest Service granted permission for a fleet of snowmobiles and all-terrain vehicles to finish the job.

Today, the Dorothy Molter Museum sits in a woodsy area at the edge of town, offering visitors a sudsy sample of root beer and a taste of life at her fishing camp. Visitors can stroll a quarter-mile nature path and birding area, and gaze at signs that Molter painted with her simple advice: “Kwitchurbeliakin.” The gift shop sells both six-packs of Dorothy’s Pine Island Root Beer and, for those truly inspired by Molter’s life, a brew-it-yourself root beer kit.

Although those who personally knew Molter have become rarer over the years, the museum remains as a testament to the rewards of a rustic life. Photos of the smiling white-haired woman, clad in jeans and a flannel shirt, often holding a giant northern pike, beckon visitors to appreciate Molter’s decidedly un-lonely life as “the loneliest woman in America.” As a monument to Molter, the museum invites guests to give the outdoors a try, if only for a day or two—accompanied, of course, with a frosty bottle of root beer.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook