Eclipse Maps Entered a Golden Age Thanks to Edmond Halley

In the 18th century, the English astronomer created a new appreciation for these celestial events.

In 1715, Edmond Halley published a map predicting the time and path of a coming solar eclipse. Today the astronomer is most famous for understanding the behavior of the comet now named for him, but in his lifetime he was a hotshot academic, elected to the Royal Society at age 22 and appointed the second Astronomer Royal in 1720. He was fascinated with the movements of celestial bodies, and he wanted to show the public that the coming event was not a portent of doom, but a natural wonder.

When the Moon’s shadow passed over England, Halley wrote, if people understood what was happening, “They will see that there is nothing in it more than Natural, and nomore than the necessary result of the Motions of the Sun and Moon.”

The map he created shows England with a broad, gray band across it, with a darker patch within that shows how the moon’s shadow would pass over the land. It was simple and clear—a piece of popular media as much as a scientific document. His work heralded what Geoff Armitage, a curator at the British Map Library, calls “the golden age of the eclipse map.”

“True eclipse maps, in the sense of geographical maps showing the track of eclipses, are a phenomenon of the eighteenth century onwards,” Armitage writes in his book The Shadow of the Moon.

Astronomers have studied the patterns of solar eclipses going back millennia and had some success in predicting their arrival. But as 18th-century astronomers sharpened their understanding of the solar system and the motion of the Earth, Moon, and planets, they were able to predict the paths of solar eclipses with unprecedented accuracy. With his original 1715 map, Halley included a plea for observational data—“A Re-quest to the Curious to observe what they could about it, but more especially to note the Time of Continuance of total Darkness.”

His original predictions, it turned out, were off, but only by a bit. After collecting data from his citizen scientists, Halley updated his original map. He had predicted the time of the eclipse to within four minutes, but had the track of it off by about 20 miles—surely a disappointment for anyone in that band of uncertainty. But the work remains a remarkable achievement, and he was confident enough in his calculations that the second version of the map included a prediction of a future eclipse, in 1724, as well.

Part of the reason that 18th-century scientists produced groundbreaking eclipse maps is that there were so many eclipses in this time period—two annular and five total solar eclipses in the British Isles alone, which is a greater frequency than normal. Popular publishers (John Senex and Benjamin Martin, in particular) wanted to produce broadsides that could help inform the public about the terrifying wonder that would cross the sky.

With each eclipse, the maps iteratively improved. For the 1736 annular eclipse, for instance, Thomas Wright, a self-taught astronomer, land surveyor, and instrument maker, created a map that adopted Halley’s design but added visualizations of what the partial eclipse would look like outside the path of totality.

British scientists weren’t the only ones working to improve predictions and public communication about eclipses. In the 17th century, Dutch astronomers had created some early eclipse maps that set the stage for the 18th-century advances to come. In the 1700s, German scientists excelled at creating maps that focused on particular scientific themes.

With each eclipse to pass over the British Isles, publishers became more savvy about promoting the event to the public. In 1737, mathematician and astronomer George Smith published a predictive eclipse map in The Gentleman’s Magazine, which is thought to be the first eclipse map published in a popular publication (as opposed to as a stand-alone broadside). By 1764, wrote historian Alice N. Walters in a 1999 paper published in History of Science, “so many eclipse maps were on the market—each with a different prediction—that one commentator likened the competition between them and their producers to an event quite familiar to the English public: a horse race.”

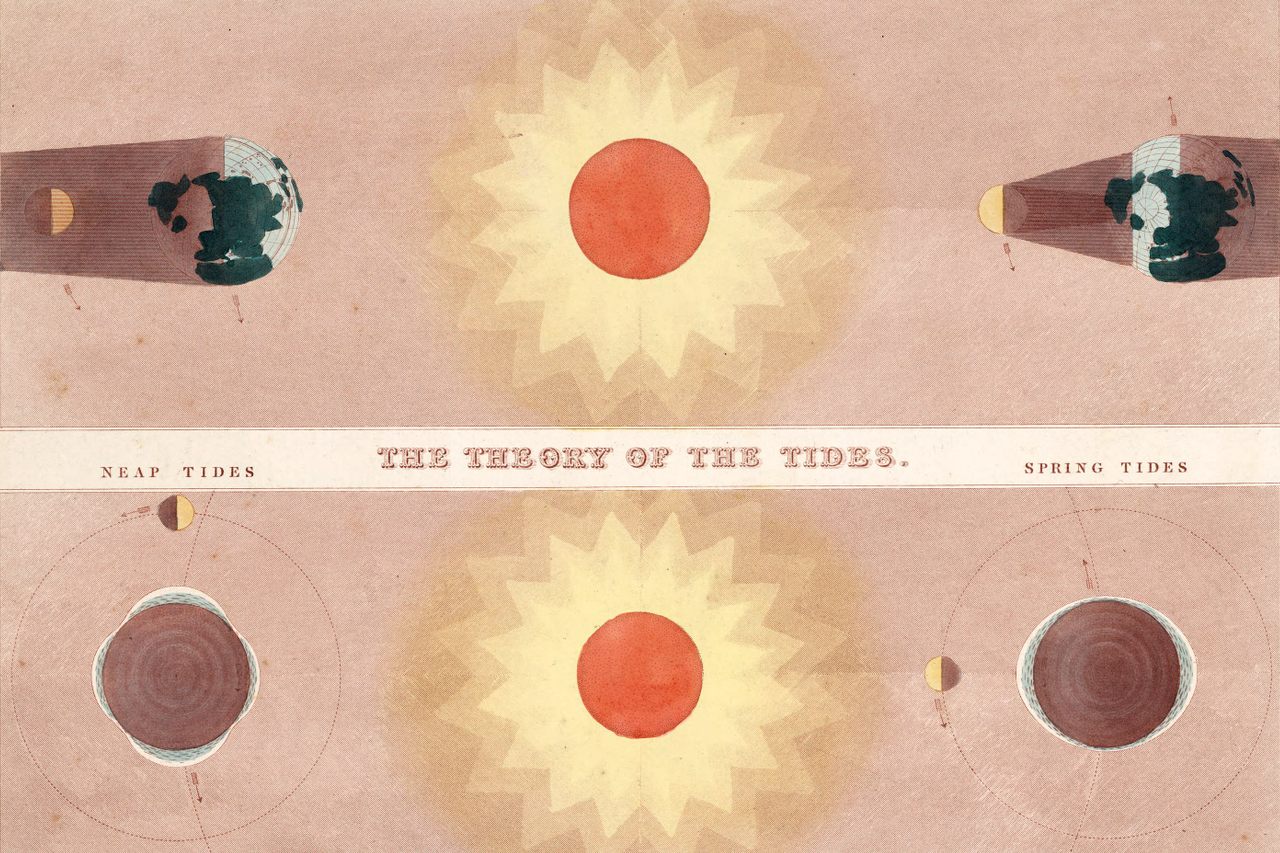

In the 19th century, eclipse mapping continued to advance, and accurate predictions became a matter of course. The most scientific maps took on utilitarian aspects and were less likely to have the aesthetic, public-pleasing qualities of their 18th-century forebears. At the same time, though, beautiful data visualizations that tried to communicate the essence of eclipse science started appearing in almanacs as well.

With these maps, the darkening of the sky became a knowable phenomenon and, as Halley hoped, “the suddaine darkness wherein the Starrs will be visible about the Sun, may give no surprize to the people.” Instead of an ominous portent, the solar eclipse became an event to look forward to.

This piece was originally published in 2017 and has been updated as part of Atlas Obscura’s Countdown to the Eclipse, a collection of new stories and curated classics that celebrate the 2024 total solar eclipse and the Ecliptic Festival in Hot Springs, Arkansas.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook