The Shocking Sex Lives of Electric Eels in Brazil

Lightning and other environmental electricity may jumpstart reproduction for the Amazon Basin fish.

Nonato Mendes ignored the leeches squirming underneath his T-shirt. With a deep breath, he plunged his gloved hand into the net that was piled on the deck of the boat, grabbing the electric eel behind its head. Skillfully keeping its writhing body away from him, he avoided the excruciating jolt—eight times stronger than a police-issued taser. It was his 96th capture that year, the last needed for his field research.

For more than 20 years, Mendes, a federal environmental agent at Brazil’s Instituto Chico Mendes and a Ph.D. student at the University of São Paulo, has unraveled the enigma of electric eels. Now, after a decade of analysis, he believes he’s cracked one of their biggest secrets: their spawning behavior and the environmental conditions that drive it.

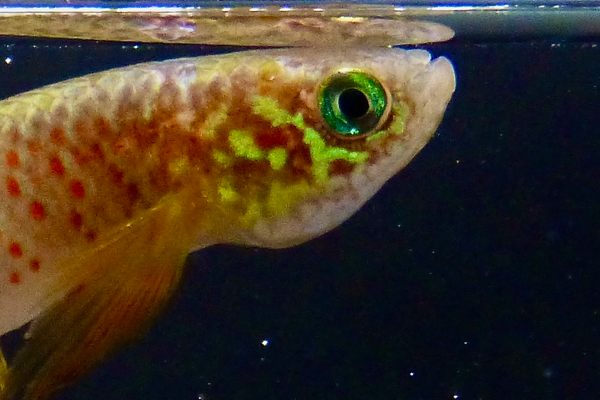

Electric eels, immediately recognizable with their pudgy, scarred bodies, wide mouths, and beady eyes, are the apex aquatic predators of the Amazon. “People fear them even more than jaguars; you see a jaguar, but you don’t see these fish until you step on one in the river and get electrocuted,” Mendes says.

Native to the rivers of the Amazon basin and the Guianas, electric eels are not true eels; they actually belong to the knifefish family. The three species in the electric eel genus Electrophorus generate powerful shocks to catch prey and defend themselves—a trait that sparked Mendes’s curiosity from an early age.

Growing up in the northern Brazilian city of Macapá, where the Amazon River meets the Atlantic Ocean, Mendes, who has autism, became fixated on electricity—his father was an electrician—and later the natural world. During fishing trips, he discovered the electric eels that lurked in a local lagoon. They were the perfect fusion of his passions.

Over the years, Mendes has uncovered new details about the animals’ hunting techniques and other behavior. Yet their reproductive biology remained elusive. Electric eels are popular fish in aquariums and zoos, but breeding them in captivity has proven nearly impossible—figuring out how to do so would reduce captures of wild eels.

Conventional thinking was that electric eels spawned during the peak of the dry season, when breeding pairs occupied the isolated pools that formed as rivers receded. But no field study had confirmed this, leaving the timing of their breeding season an enigma. Mendes, intrigued, set out to solve the mystery.

In 2005, Mendes set up base on the Curiau River floodplain in his home state of Amapá for a year-long study on the Vari’s electric eel (Electrophorus varii), the most primitive electric eel species. He recruited local fishermen to help.

Luis Sousa, a longtime Curiau River fisherman who became one of the project’s field assistants, says the secret to finding the eels is no secret at all: “You find the fish it eats. So, we know where to look for them because these spots mean good fishing.”

Equipped with shrimp nets, cast nets, and hand lines, the team set out by boat every two months to capture enough specimens to gather data on size, weight, stomach contents, and gonad development, which signals whether the animals are ready to reproduce. Yet electric eels don’t take kindly to being caught. Thick rubber gloves offered some protection from electric shocks, but an occasional electrocution was just par for the course. “It’s agony,” says Mendes. “First, every muscle in your body contracts; then, you get intense pain. After, there’s numbness and exhaustion—you feel wiped out.”

Fieldwork had other hazards, too: Swarms of mosquitoes and legions of leeches feasted on the researchers’ blood and encounters with the highly venomous Fer-de-Lance viper were frequent. The team persevered, and even before the last eel was caught, Mendes noticed a pattern.

As the Amazon’s rainy season arrived and torrents of rain swelled the rivers, the team began to catch eels with gonads almost bursting with sperm or eggs. Later analysis of the data revealed a possible mating trigger—one particularly apt for an electric fish.

“My hypothesis is that it might be electrical conductivity in the water caused by the rain and atmospheric conditions, maybe even lightning, that drives electric eels to begin spawning,” says Mendes. But even armed with this data, it would take more than a decade of painstaking analysis before he published his discoveries in 2016.

“The rising water period triggers a lot of behaviors in South American fishes, and for fishes to be using that cue to synchronize breeding would make a lot of sense,“ says Mark Sabaj, an ichthyologist at the University of Drexel, who wasn’t involved in the research. Mendes’s reputation in the field adds credibility to the hypothesis. Notes Sabaj: “I would buy into it as his knowledge and personal experience of these fish far exceeds anyone else’s. He’s like the electric fish whisperer.”

Mendes’s research revealed another surprise: Female electric eels prefer large mates, the bigger, the better, possibly because of the males’ outsized role in parental care. The larger the eel, the more powerful its electric discharge, giving big males an advantage when competing for and defending prime nesting spots, as well as protecting their young.

“Males guard the offspring for about four months until the moment they disperse, which is an amazing investment of time,” says Douglas Bastos, a researcher at the Instituto Nacional de Pesquisas da Amazônia (INPA) who has studied the behavior. “During this period, they are very attentive to their young, and hyperaggressive in defending them.”

Beyond potentially solving some scientific mysteries, the research could soon have some benefits for the eels themselves. Currently, all global demand for the animals is met by collecting wild specimens from the Peruvian Amazon. While this trade remains sustainable and electric eels are not endangered, Mendes believes his findings may one day eliminate the need for capturing them from the wild.

To test out whether his theory is correct, Mendes plans to try replicating the environmental conditions that trigger wild spawning in a captive setting. “I think we’ll achieve the first-ever breeding in captivity,” he says. “But it’s not just about the science. If it means wild electric eels can stay in the rivers, where they belong, I’ll be very happy.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook