The Secret London Exhibition for Spies’ Eyes Only

During World War II, the Natural History Museum showcased tools for sabotage.

When Ealing Studios released a feature film in 1948 that showed a secret wartime spy workshop hidden in London’s Natural History Museum, the plot was too far fetched for critics and the public. The New York Times said Against the Wind conveyed only “a minimum of the truth” behind Second World War sabotage efforts. Its director Charles Crichton—perhaps best known for the comedy A Fish Called Wanda—was also rebuffed: “Only Crichton would think of having his secret London headquarters in a museum of stuffed dinosaurs” scoffed one critic.

Half a century later, a series of documents emerged that would have astonished Crichton’s skeptics. In the 1990s, after the British government released formerly classified intelligence files from the Second World War into the public domain, historians were finally able to access an official history of the Special Operations Executive, a secret department created by Winston Churchill in 1940 to undertake sabotage in enemy territory. Crichton’s story, it turns out, was more plausible than it had initially appeared.

The Special Operations Executive recruited, trained, and briefed agents for missions abroad, and had a camouflage section to ensure that agents were supplied with the complex disguises and means of concealing weapons needed to reach and attack foreign railways, military vehicles, and factory machinery without being caught.

To do this well, the camouflage section relied on insight about an agent’s designated territory from the SOE’s country specialists. Everything from photographs of popular brands of cigarettes, to news that the rationing of rubber had impacted the size of heels being produced for womens’ shoes, was considered important. When an agent in France reported that a ban on coal had made it a risky carrier for explosives, the camouflage section created incendiary logs made to match the region’s most common trees instead. According to archive records, its attention to detail even extended as far as agents’ collar button holes, which in England were affixed horizontally, but on the continent were sewn on vertically.

The SOE employed a film director to head the camouflage section. Lieutenant-Colonel J. Elder Wills initially operated from a workshop in the Victoria and Albert Museum with a small team of mostly prop-makers recruited from the film industry—many of the briefs sent to the camouflage section required imagination and unusual production skills. In fact, one of Wills’s early recruits, Walter Bull, a plasterer responsible for producing exploding coal, later went on to become the chief plasterer on 2001: A Space Odyssey.

As the organization grew, the SOE acquired a number of stations. The proximity of the Thatched Barn—a hotel on the Barnet Bypass acquired from Billy Butlin, founder of the famous holiday camps—to Elstree film studios made it useful for dealing with large-scale production. Meanwhile the sites in London’s Kensington neighborhood dealt with prototypes and housed the country specialists. Another building at 2-3 Trevor Square hosted a photographic section responsible for producing agents’ fake documents. The author Leslie Bell tells a compelling story in the 1957 book Sabotage! about a number of specially selected women from the Auxiliary Territorial Service who were employed to appear at the door of SOE bases dressed as ordinary British housewives in the middle of household chores so as to ensure that deception was maintained.

The HQ for the country specialists was not far from the west wing of The Natural History Museum, which had sent its valuable exhibits off for safekeeping in the countryside for the duration of the war and closed its doors to the public. One of its former employees, a crystallographer called Dr. Frank Claringbull, had joined the SOE as an explosives advisor (and became the museum’s director in 1968), but this was not the extent of the Natural History Museum’s connection to SOE. In a somewhat unusual turn of events, the camouflage section acquired the west wing, with the help of the museum’s then-director Sir Clive Forster Cooper, and filled it with it a private display of explosives, camouflage, and vehicles used by SOE agents.

It is not entirely clear why the Special Operations Executive created the secret exhibition, nor is it apparent why they held it in a sealed-off section of the very well known and centrally located British institution. As the author Mark Seaman notes in The Secret Agent’s Handbook of Special Devices, the camouflage section claimed that the exhibition was created “in order that the Agent should receive every possible help and avail himself of ‘food for thought.’” But it was also recorded that attendance was low and relatively few members of SOE actually took advantage of the opportunity to examine the latest inventions. King George VI, however, did not decline the opportunity, nor did Sir Robert Bruce Lockhart, the Director-General of the Political Warfare Executive, who wrote in his diary that it was:

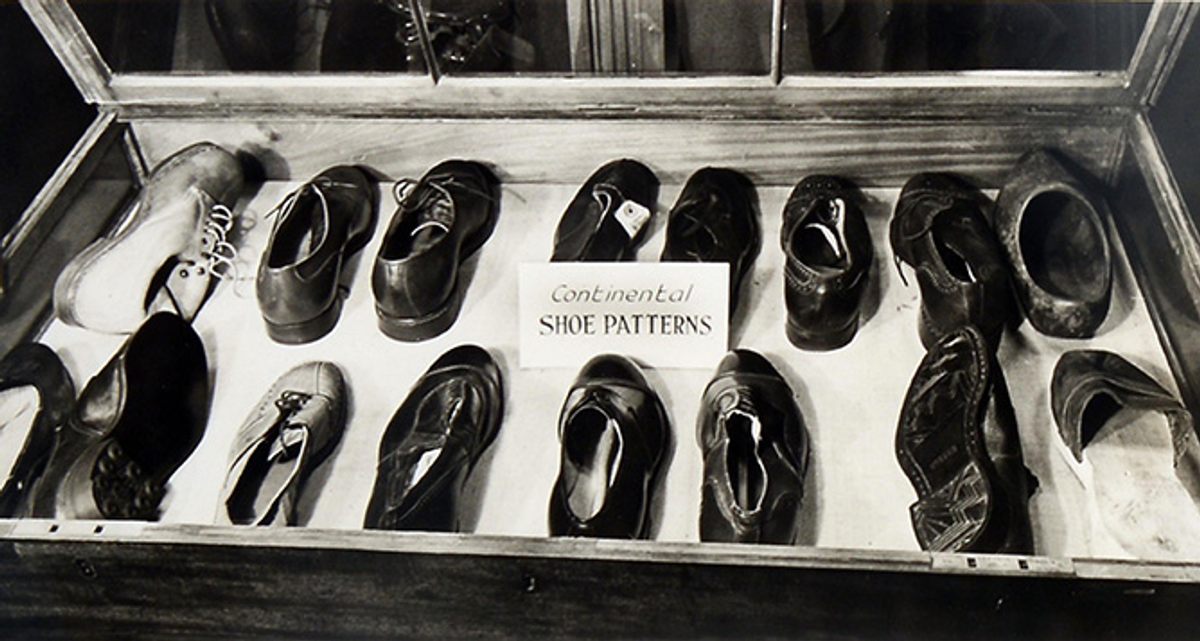

“Most interesting and very well done. One exhibit showed ties, shirts, underwear, etc of continental manufacture showing the difference from British makes. Likewise shoes. Most ingenious, too, were the blocks of wood, spars of ships, petrol tins, etc, used for concealing radion sets and even tiny but useful motorbikes, not to mention arms, tommy-guns, etc. Also very ingenious containers and one-man submarines, also many kinds of disguised bombs and explosives which stick to ships. A good show.”

Rumor has it that J. Elder Wills created the exhibition as a public relations tool for persuading other departments to support the work of the camouflage section and the SOE in general, which perpetually experienced difficulties in convincing the War Office that they needed unusual personnel, such as artists, prop makers, and property agents, instead of the usual “army tradesmen.” The SOE operated independently from the Secret Intelligence Service, and the two were often competing for resources and facilities—the head of the Secret Intelligence Service, Sir Stewart Menzies, was famously outspoken about the SOE and did not hesitate to denounce them as “amateur, dangerous, and bogus.”

Although other historians had written about the exhibition when the intelligence files were released in the 1990s, the Natural History Museum’s connection to SOE wasn’t recorded in the museum’s official history until the early 2000s when one of its crustaceans experts, Dr. Paul Clark, was tipped off about the secret exhibition by his father, a former flyer for SOE during the war. From the records released into the public domain, Clark was able to map the spy exhibition to the layout of the museum and discover that the exhibition began at what is now “the mammal gallery,” just off the left of the Hintze Hall.

Clark proved it is possible to match up the interior architecture visible in photographs with the gallery space as it exists today. An archway that hosts a bench for weary museum visitors was then host to a display case of Balinese carvings designed to conceal explosives for agents in Southeast Asia. A wall of taxidermied porcupines and bears was once occupied by wireless sets. Behind the case at the end of the gallery that now hosts a stuffed polar bear, there was a door to a room of machine guns and pistols.

A parallel gallery featured explosives: incendiary Chianti bottles, cigarettes, and “tire busters” designed to match the geological structures of different stones. You could also find an explosive rat here—skinned by a former bacon hand at the grocer Sainsbury’s—which succeeded in undermining the Nazis’ efforts despite never being detonated. A history of the camouflage section reports that after an unsuccessful operation led to the rat’s discovery, the Germans were so paranoid about whether dead rats were explosives or not that “the trouble caused to them was a much greater success to us than if the rats had actually been used.”

After the defeat of Germany, there was little need for the SOE’s activities to continue and it was formally shut down in January 1946. The Natural History Museum’s exhibits were returned and the institution reopened to the public. Many of the SOE inventors, designers, and craftsmen returned to their former roles. A career history for J. Elder Wills held by the British Film Institute shows that he returned to the film industry after the war, mostly as an art director for films that happened to have plots about blackmail and deception. The only anomaly in his list of art directing experience is a credit for a story he told that was made into a film in 1948—Charles Crichton’s Against the Wind.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook