The Scholar Mapping America’s Forgotten Feminist Restaurants

Challenging patriarchy, one eatery at a time.

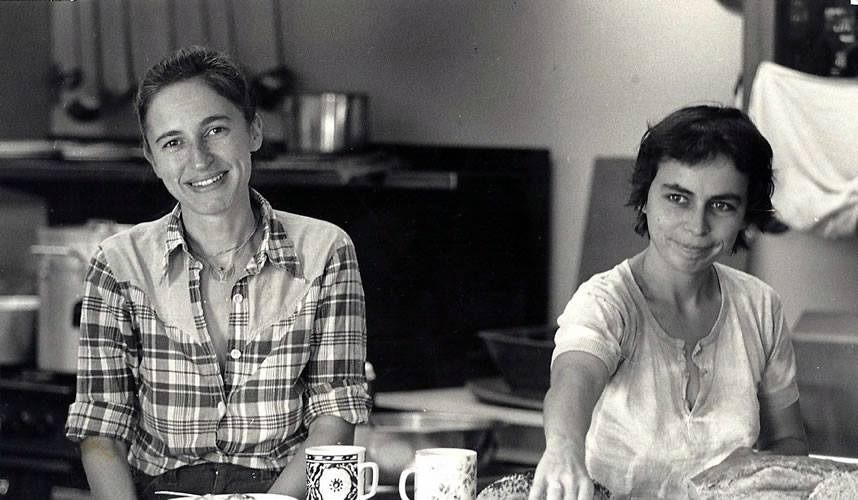

There are no waitresses at Bloodroot restaurant. There’s no meat, either. When a small collective of women founded the Bridgeport, Connecticut, café and bookstore in 1977, they eliminated both meat and table service as part of a sweeping feminist vision. Bloodroot would be a restaurant led by women, for women; a restaurant where respect for workers, animals, and the earth was as important as delicious food. Four decades later, Bloodroot is still run by founding members Selma Miriam and Noel Furie.

Bloodroot’s founders weren’t alone in their feminist vision. From the 1970s to the 1990s, according to Dr. Alex Ketchum, a professor of gender, sexuality, and feminist studies at McGill University, at least 250, and perhaps as many as 400, feminist restaurants, cafes, and coffeehouses opened in the U.S. and Canada. Almost all of these restaurants are gone. But for two decades, establishments from Alabama’s Steak n Eggs to the Canadian Yukon Territory’s Rendez-vous Coffeehouse challenged women’s traditional consignment to to the home by reclaiming cooking for the feminist movement. The feminist restaurant was “a place where community could be built around food,” Ketchum says. “Places where cooking wasn’t antithetical to women’s liberation.”

For years, Ketchum has been mapping these largely forgotten eateries—a research project sparked, in part, by a visit to Bloodroot in 2011. At the time, she was an undergraduate and passionate about the food justice movement. Yet something was bothering her. While movements oriented toward sustainable, local food celebrated home-cooked meals, they glossed over who was doing most of the cooking: women, usually without compensation or recognition. Curious to discover how feminists had addressed this tension, Ketchum and her friends piled into a car and went to Bridgeport. What she found there—a bright restaurant filled with books, political posters, and a rotating menu of vegetarian specials—propelled a passion that became a PhD dissertation, a published guide and forthcoming book, and the most complete record we have of the establishments that fed second wave feminism.

While explicitly feminist restaurants first opened in the 1970s, politically oriented, women-run eateries began with the suffrage movement. New York City’s The Suffrage Cafeteria, which opened in 1912, served cheap, filling meals on china stamped with the slogan “Votes for Women.” Affordable meals enticed guests to enter; once they were inside, activists set to work convincing them to support suffrage. In the U.K., suffragettes opened The Minerva Café, which became a hotbed of socialists, women’s rights advocates, and sundry radicals. The Café, like many of the suffragettes who ate there, was vegetarian, reflecting a political aversion to killing animals that would continue into second wave feminism. The restaurant’s china sported the Women’s Freedom League’s motto: “Dare to be free.”

Despite this radical history, post-World War II conservatism sought to re-entrench middle class women firmly back in the home. That’s partly why the second wave feminist movement began with a critique of housework. Nowadays, we tend to talk about Betty Friedan, author of The Feminine Mystique and co-founder of the National Organization for Women, as a discontented housewife. In fact, she started her career as a journalist for labor unions. In her classic book, she took this concern for labor and placed it squarely in the home. Throughout the ‘60s and ‘70s, feminists continued to challenge the expectation that women provide unpaid cooking, cleaning, and childcare services. Some, like radical feminist Shulamith Firestone, envisioned mechanized utopias, where babies would be made in artificial wombs and women would be freed from the shackles of the stove.

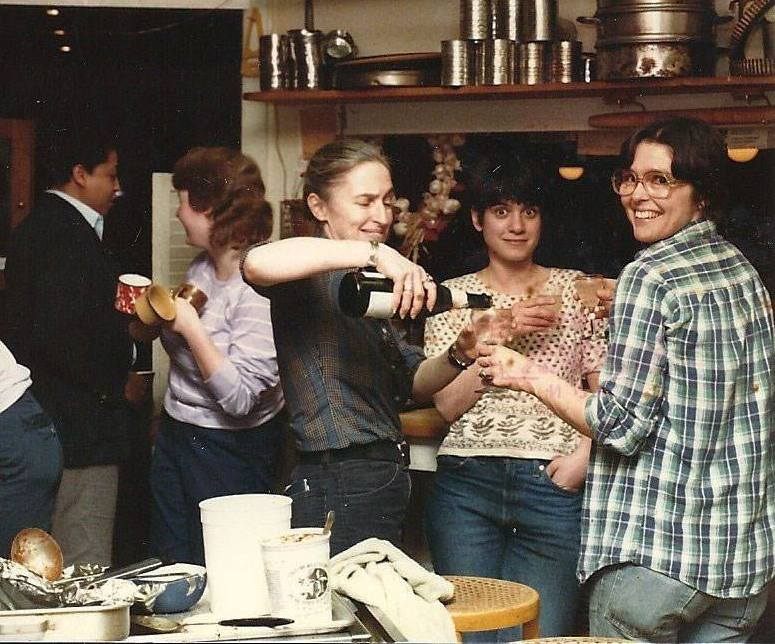

For others, power was in the kitchen. Whereas suffrage restaurants had been about converting men to the cause, second wave feminist restaurants were for women, by women. The first was Mother Courage, opened in 1972 in New York City’s West Village. Founded by Dolores Alexander and Jill Ward, Mother Courage was a home base for the city’s radicals, where activists could strategize and single women could congregate without fear. The idea took off: By 1989, says Ketchum, as many as 400 feminist restaurants had been opened across the United States and Canada.

These restaurants provided a way for women, historically barred from dining out without a male chaperone, to claim public space. But they also helped women to reclaim the kitchen, for their own nourishment and on their own terms. Rather than rejecting cooking for its patriarchal connotations, feminist restauranteurs crafted an egalitarian vision of fairly compensated, collective kitchen work, where dining enabled political organizing, collaboration, and pleasure.

These restaurants weren’t always focused on the food. At Susan B’s, a Chicago-based soup restaurant which was open from 1975 to 1991, one founder, when preparing for the grand opening, realized she didn’t actually know how to make soup. “It was about having a place where women could congregate and socialize and eat,” says Ketchum. “Soup was the vehicle.” Yet for other restaurants, such as Bloodroot, food was politics. For these women, vegetarian, locally sourced, ethnically diverse, and delicious food signified a connection to the earth and to each other. While they had different relationships to the pleasure and politics of eating, however, all feminist restaurateurs shared a critique of the service industry. Many were self-service, eliminating waitressing and tipping, practices that often lead to economic precarity and sexual harassment for women workers.

In the always erratic restaurant industry, this commitment to radicalism was tough to sustain. White, straight women already faced barriers to obtaining credit; for lesbians and women of color, the financial hurdle was even higher. Meanwhile, maintaining political commitments to quality food, good working conditions, and accessible prices was an ongoing challenge. “It’s a triangle that’s really hard to balance,” says Ketchum. Burnout and infighting were a common result. All told, most feminist restaurants lasted less than two years.

By the 1990s, the number of feminist restaurants was in decline. The AIDs crisis devastated LGBTQ communities, and many lesbian women found themselves organizing with gay men, rather than with straight women. The landscape of American feminism was also changing, as the collectivist orientation of the ‘70s was replaced by a more individualistic, even capitalist, ethos. Today, most of the women’s and lesbian spaces that characterized that golden era, including feminist restaurants, bars, and bookstores, are closed.

Bloodroot, however, remains open, continuing to welcome customers with its political integrity, vegan quiches, and delicious chocolate devastation cake. It’s the latter menu item, a vegan sweet with a sourdough base, that has special meaning for Ketchum. When she turned in her bachelor’s thesis, which included research informed by Bloodroot’s Miriam and Furie, the two owners served her a slice of the famous cake.

In 2018, when Ketchum defended her PhD dissertation on feminist restaurants, she presented a roomful of examiners with her own version of the cake. It was an unusual move for an academic setting. The university, after all, has long been a target of feminist criticism, its hallowed halls full of the busts of white male scholars with little recognition of women whose domestic, emotional, and intellectual labor makes the institution run. For Ketchum, the move was obvious. “How can we talk about food without eating?” she asks. “So I cooked the cake, and I served it.”

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook