Setting Furnished Rooms Ablaze at the Fire Research Lab

The facility allows investigators to recreate arson attacks and analyze burn patterns.

The room is always laid out according to exact specifications. A nylon sofa by the wall. A dark faux-leather La-Z-Boy in the corner. A lamp here and a television there. Perhaps a wool rug hugging the floor with a wood coffee table on top. Maybe there’s even a bag of potato chips on the table. However it’s arranged, wherever each piece of furniture is placed, it often feels and looks like a typical American home. Then, they set it all on fire.

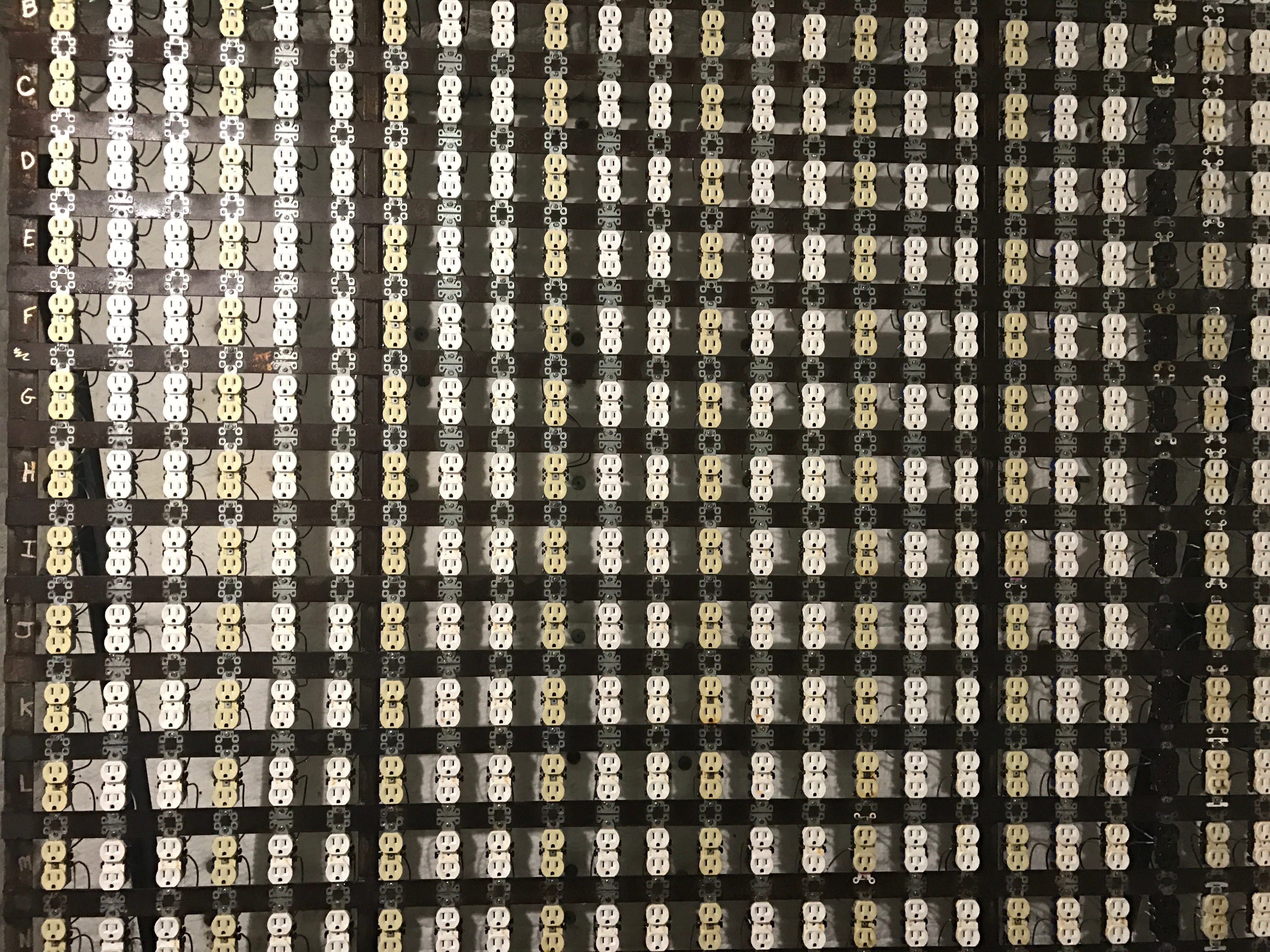

Welcome to the ATF Fire Research Laboratory in the leafy D.C. suburb of Beltsville, Maryland. This is the world’s largest and most advanced research lab dedicated to fire scene investigations. It’s here, 20 miles outside of the United States’ capital, in a giant warehouse that resembles more a Hollywood soundstage than a science lab, where scenarios are played out once, twice, a dozen times to see if a fire is the result of an innocent accident or malicious intent. In this cavernous building with an gigantic exhaust hood that looks like a space shuttle jet engine, they construct three-story structures only to reduce them to ashes. They bring in perfectly comfortable mattresses and set them ablaze. They turn up electric heaters one would purchase at WalMart or Target to see if they’ll ignite.

They do all of this because fire is a notoriously confusing culprit, with clues of its origin often destroyed by its very nature. “Any crime scene is very complex, there are so many pieces … and, then, you set it on fire,” says John Allen, forensic electrical engineer and Chief of the ATF Fire Research Lab.

In the 1950s, Harvard professor Howard “Mr. Fire Research” Emmons earned his nickname by applying science to firefighting and prevention. He knew that by figuring out the “what” in a fire scene, it could often lead to the “why” and “how.” He was known to set his own office furniture on fire to test theories. While flames raged, he tracked and took notes on every possible variable that could be impacting the fire—the materials in the burning chair, the air flow in the room, the components of the paint on the wall. His mission was to test every possible scenario and miss nothing. As Emmons wrote in 1986, “The ultimate purpose of fire science is to remove the guesswork.”

The ATF Fire Research Laboratory is a direct descendent of Emmons’ work. Part of a $135 million facility completed in 2003, the fire research lab has around 30 employees working on hundreds of cases a year attempting to establish the what, how, where and sometimes even the who of a destructive fire. And they’ve worked on some very high profile cases: 2013’s West Texas Fertilizer Plant Explosion. A fatal home fire fueled by a Christmas tree in 2015. Bringing to justice one of the most prolific serial arsonists in American history. A natural gas explosion that destroyed an apartment complex. The massive Da Vinci fire in downtown Los Angeles. A Texas mosque destroyed by fire earlier this year. ATF and the lab has also been brought in on international cases, like 2012’s infamous Comayagua Farm Prison fire in Honduras.

Big or small, every case is unique, complex, and hard. After all, arson is a federal crime and, depending on the laws in the relevant state, may be punishable by death. “Every time I testify, my career is on the line,” says Allen. “[If we’re wrong] we are done.”

That’s why the ATF is so meticulous about its test burns. Several large burns (such as a two-story structure) are conducted in a year, but smaller burns—like setting fire to a chair or carpet—are sometimes done a few times a day. Big or small, they catalog an enormous amount of data using high-tech instruments, HD video, and a giant exhaust hood (connected to a state-of-the-art exhaust system) that hangs from the ceiling and over the proceedings. The temperature of the fire, air velocity, voltage, smoke density, the time of day, and heat flux are just a few examples of what’s recorded.

Allen explains that they run “real-life scenarios,” meaning they need to make sure every piece of furniture in their scenario matches the original scene. That could mean buying out the local Ashley Furniture of all their La-Z-Boys or knocking on the neighbor’s door. “We’ve gone into someone’s house and said ‘we need your carpet,’” says Allen, “and we have to buy it off them.” But it goes further than that. Newspapers, toys, books and, even food that was in the room at the time of the fire needs to be accounted for. “Potato chips, because of all the oil....[they’re a] great [fire] accelerator,” says Allen. “Fritos too,” pipes in Chad Campanell, ATF Senior Special Agent and Certified Fire Investigator.

Campanell is one of 117 certified fire investigators across the country whose job is to go out into the field to fire scenes of federal interest and starts putting the puzzle together. He wades through ash and burned husks of buildings collecting evidence, photographing burn marks and looking for clues about how it all started. If it’s a possible case of arson, he brings everything back to the lab to continue the dig. However, he knows that this could all lead to his original hypothesis being disproven. Says Campanell, “If there’s no data to back [my hypothesis] up, there’s no case … Science doesn’t have a bias.”

Both Allen and Campanell say that there are plenty of times that a case may look like arson at first glance but is actually a tragic accident. Faulty or malfunctioning electrical connections causes over a billion dollars in property damage a year in the United States. Allen is in the midst of researching how certain older garage door openers can open on their own when exposed to high temperatures, making a mechanical malfunction look like a potential break-in. And cats have a reputation for turning stove knobs when hopping on counters. Although, perhaps the felines are doing this on purpose.

Every day at the lab, investigators are attempting to distinguish between arson and accident. Through science, meticulous collecting of data and burning stuff down, they are getting the job done. Nowhere is the old proverb “fight fire with fire” more apropos than at the ATF Research Laboratory.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook