The Oldest Cookbook in Korean Was Written by a Genius Noblewoman

A poet and artist, she penned the recipes in her old age.

When Jo Gwi-bun married Yi Don in the 1980s, he handed her a book of his family’s recipes and insisted she use them. “Of course, I had never heard of the book before, and I had no idea how to read the text. It wasn’t even written in modern Korean!” the 71-year-old woman, now known as Lady Jo, exclaims.

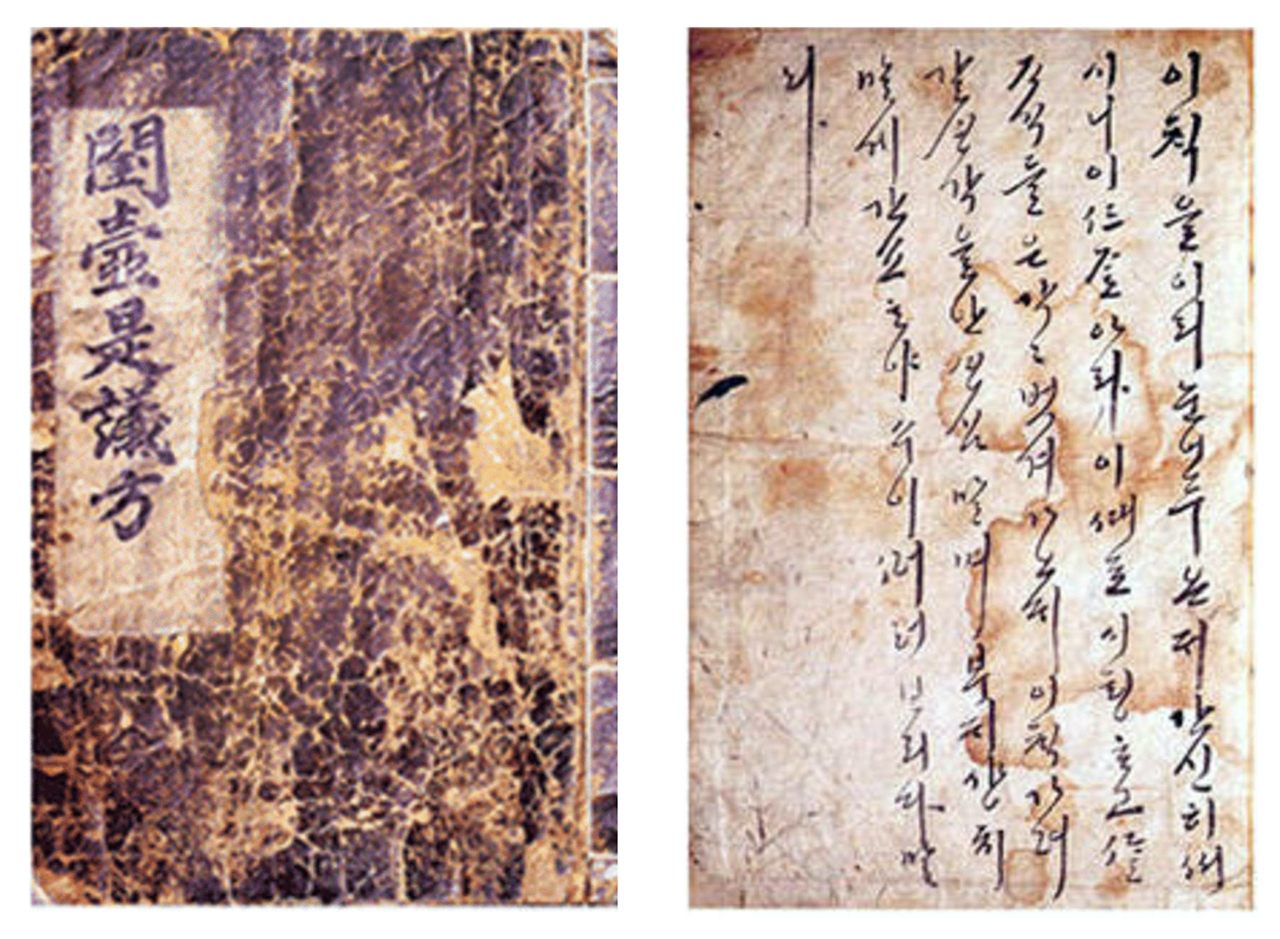

Lady Jo soon discovered the book was no ordinary compilation of family recipes. Instead, it was a centuries-old artifact credited as the first-ever cookbook in hangul, the Korean alphabet. Written by Lady Jang Gye-hyang around the year 1670, the manuscript is titled Eumsik-dimibang, or “Understanding the Taste of Food.” Some historians even believe it could be the first cookbook written by a woman in all of East Asia.

Currently on display at the library of Kyungpook National University (KNU) in Daegu, South Korea, Eumsik-dimibang introduces approximately 146 dishes in 30 pages of elegant calligraphy. The food-related texts that preceded Eumsik-dimibang use Chinese characters, legible only to the elite, and focus on agriculture and the medicinal uses of food. Lady Jang’s account, on the other hand, guides the reader on everything from storing fruits to distilling Korean liquors.

Practical value of the book aside, no story of Eumsik-dimibang could be complete without recognizing that it was written by a woman, in a time when educated women were few and far between. Born in 1598, Lady Jang was the only daughter of a prestigious scholar in a yangban (noble class) home. At the time, society adhered strongly to Neo-Confucian values, meaning that women were barred from higher education. But Lady Jang taught herself, by eavesdropping on her father’s classes and prying into his books. In a short period of time, she established herself as a painter, calligrapher, and poet. Over the centuries, the Korean public remembered Lady Jang for her poems of her youth, such as “Ode to the Saint” and “Crane White Hair,” and not for Eumsik-dimibang, which she would write much later in life.

When Lady Jang turned 19, her father arranged for her to marry one of his students, Yi Si-myeong. After their marriage, the two moved to remote North Gyeongsang Province, settling in Dudeul Village—a part of South Korea that remains one of the nation’s most far-flung, difficult-to-reach locales. As a married woman, her creative energies shifted to more domestic endeavors, and she occupied herself by overseeing the education of her 10 children (including two from Yi’s previous marriage). Older, conservative texts sum up Lady Jang’s life in a few words: wise mother to seven scholarly sons, and ancestor to famous writer Yi Mun-yol.

In fact, it is only in modern Korea that Lady Jang and her Eumsik-dimibang have gained distinction. Lady Jang wrote Eumsik-dimibang for her son’s wives, not for wider distribution, and intended the book to be passed down from one daughter-in-law to the next. This tradition continued quietly for centuries, until a professor and food history expert, Kim Sa-yeop, brought scholarly attention to the book in 1960. Even then, few outside academic circles knew of Eumsik-dimibang. In post-Korean War society, still rife with shortages, food was seen as little more than a means for survival until the 1970s. Lady Jang’s remarkable contribution to food history continued to go unnoticed.

In more ways than one, Lady Jo—a former teacher of home economics—was the perfect person to restore Lady Jang’s legacy. As a newlywed, she took her duties as a new member of the Yi family to heart, and quickly mastered the Eumsik-dimibang dishes while cooking for a special type of ancestral memorial service, bulcheonwi-jesa.

In the early 2000s, she helped research a contemporary interpretation of the cookbook. Published in 2006, professor Baek Du-hyun’s Comments on Eumsik-dimibang uses modern measurements and recommends commercial sauces and pastes, making it more accessible for modern Koreans unaccustomed to preparing each ingredient from scratch.

In 2010, Lady Jo and her husband heard that a Dudeul Village restaurant, which served dishes inspired by Eumsik-dimibang, was about to shut down. “How could we just stand by and watch the food of our ancestors disappear?” she says, as if declining to manage the restaurant was never an option.

Despite her convictions, moving from near Seoul to Dudeul Village, being away from their children and grandchildren, and working in a kitchen—for less than minimum wage—has not been easy. “But regardless, I couldn’t turn away from the food of my in-laws, and felt I must promote the book and keep it alive,” she says. “Once I married into this family, I had an obligation to shine a light on its legacy.”

Today, visitors to Duduel Village can make reservations to dine at the Eumsik-dimibang Restaurant and stay overnight at the Jang Gye-hyang Culture Experience Center, a beautiful hanok (traditional Korean home) outfitted for overnight guests, with an exhibition space dedicated to Lady Jang.

Lady Jo operates much of the Jang Gye-hyang Culture Experience Center—cooking, taking media requests, and teaching classes. She seems to genuinely enjoy speaking about Eumsik-dimibang, and often refers to notes on her smartphone to double-check herself. “The book does not reflect what the average person at the time was eating,” she explains. Notably, there’s no mention of gochugaru, the staple spice of Korean cuisine. Although gochugaru, made from New World chile peppers, became available during Lady Jang’s lifetime, “the book is really about the royal cuisine of her ancestors, when gochugaru was not available,” notes Lady Jo.

But what she admires the most about her ancestor-in-law is not her culinary endeavors, but her philanthropy. In one of Lady Jo’s many anecdotes about Lady Jang, she describes how the noblewoman would look down at the village during dinnertime, to see which homes did not have smoke rising from the kitchen, meaning the household had no rice to cook. She would then invite families in need to work on her land so she could feed them. “Even the term ‘superwoman’ is not enough to describe Grandma Jang,” Lady Jo says.

With a new wave of feminism in South Korea shedding a light on women’s stories, Lady Jang’s work has taken on a new depth. According to Confucian precepts held in the Joseon era (1392-1897), the biggest sin women could commit was disobedience to her in-laws. Most women saw their own parents maybe once a year. Lady Jang, in contrast, had an unusual devotion to her direct lineage: moving back home for two years when her mother died, arranging her father’s second marriage, and later, taking in his second family. She also evidenced loyalty to her own Andong Jang clan in a section of Eumsik-dimibang called Matjibangmun or “A Trip to Matji,” her mother’s hometown. In a world that valued a woman’s loyalty to her husband and his family above all, many now interpret this section of 16 recipes as Lady Jang’s assertion of her own identity.

Yet new discoveries have shown that Lady Jang may have not been the first Korean woman to inscribe her recipes for posterity. In 2015, professor Park Chae-lin of the World Kimchi Institute found a manuscript called Lady Choi of the Hae-ju Clan’s Cooking Rules while reviewing materials for Sookmyung Women University’s Museum. While mostly written in Chinese characters, Park believes it was written at least 10 years prior to Eumsik-dimibang. Not wanting to diminish Eumsik-dimibang’s importance, Park told the Joongang Daily that this find, which offers data about Chungcheong Province cuisine, gives “balance to the study of Korean food and culture.”

Ultimately, few see Eumsik-dimibang as merely a cookbook, and those who hear Lady Jang’s story care little about whether or not her book ranks first in the annals of Korean food history. Professor Ro Sang-ho of Ewha Women’s University, who has studied cookbooks by Joseon-era women extensively, writes that such texts “can be regarded as a cultural testing field in which Korean yangban women expanded the boundaries of their space.” Lady Jo, on the other hand, thinks the essence of Lady Jang’s legacy is not necessarily found in her cookbook, but in how much she put others above herself. “If today’s world could learn something from her,” she says, “it should be the idea that your life is meant to be lived for others.”

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook