Did an Enslaved Man Beat Magellan to Circling the World?

The unsung hero may have also been instrumental in defeating the colonizers.

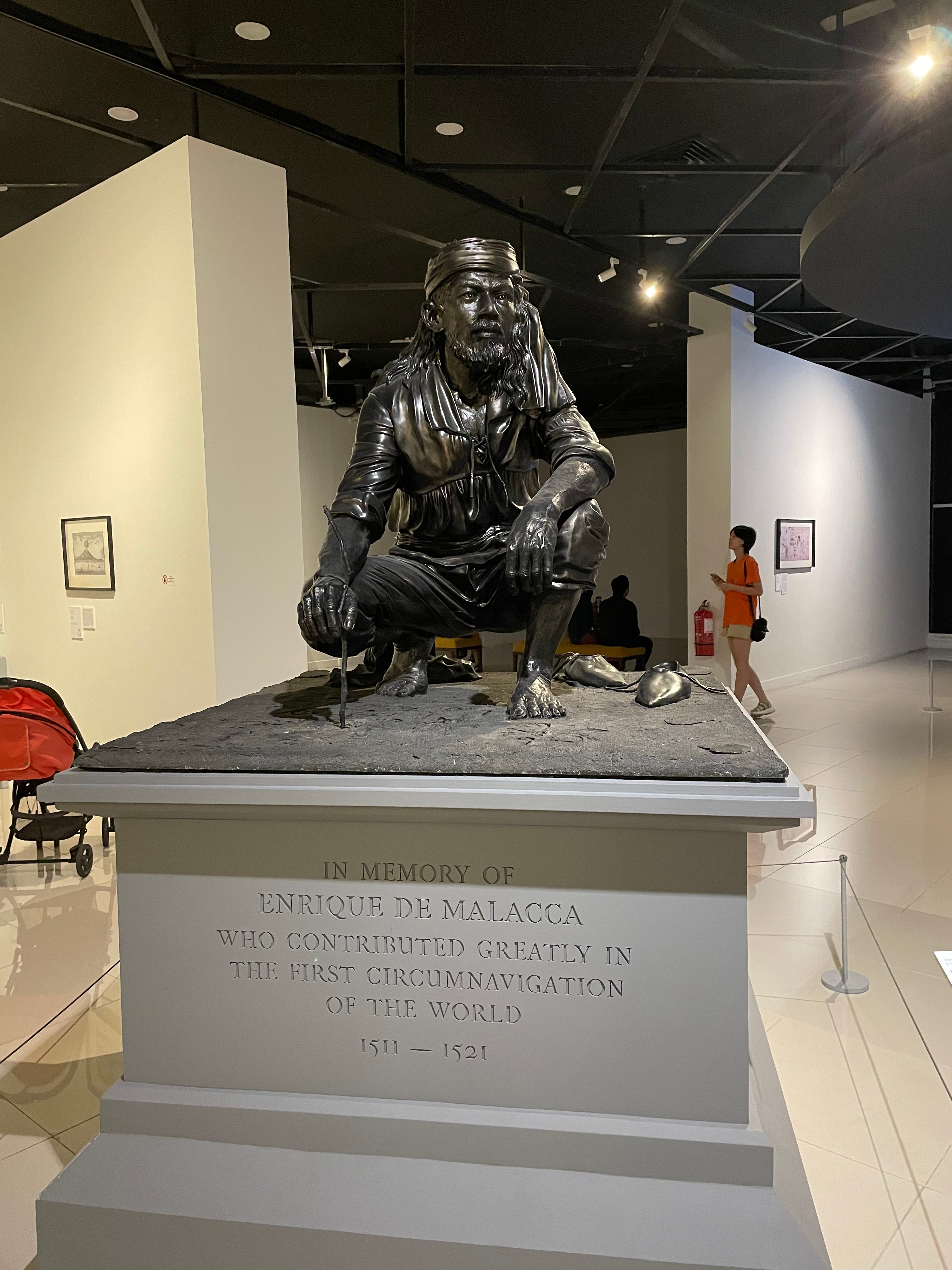

A spotlight illuminates a bronze statue in the center of a room at the National Art Gallery in Malaysia. The figure depicted is squatting with ease, elbows on thighs, long hair draping his shoulders, and wearing clothes reminiscent of a pirate or early explorer. The plaque underneath the statue reads: “In memory of Enrique of Malacca, who contributed greatly to the first circumnavigation of the world, 1511-1521.”

But exactly how great that contribution was could use some clarification. Enrique’s name is rarely mentioned in history books, if at all, yet his part is essential to the story of exploring the Earth.

“History is always like that,” says Ahmad Fuad Osman, the artist behind the Enrique of Malacca Memorial Project. “A lot of things happen that you don’t include in the record. You only say what’s important to suit your narrative.”

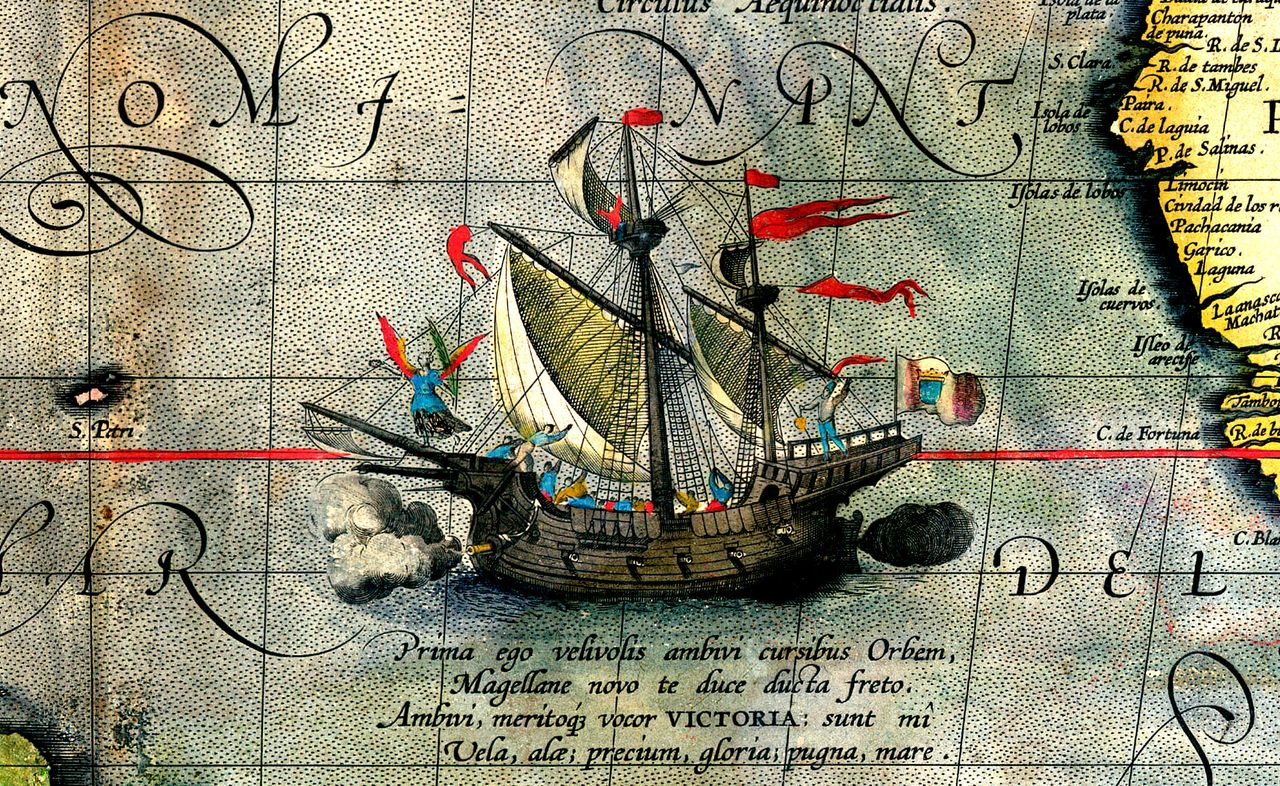

The story of Enrique is intertwined with that of Fernando Magellan, the man often incorrectly credited as the first circumnavigator of the globe. Of Portuguese descent but working for the Spanish, Magellan set sail west from Seville towards South America in 1519 with five ships. One ship, the Victoria, returned to Spain with a few dejected crewmembers in 1522, marking a complete loop around the Earth.

However, Magellan died before the expedition was completed, so he personally didn’t traverse the world. That meant the first circumnavigator title was bestowed on his co-captain Juan Sebastián Elcano, who survived the entire journey. Yet, being the expedition leader, Magellan’s name became more famous and was memorialized in history. However, that’s not the full story, and this is where Enrique, an enslaved man from Malaysia, enters the picture.

“We have a handful of references to Enrique in primary sources, but we have to use conjecture to put together his story,” explains historian and writer John Sailors, who authored the book Magellan’s Unlikely Explorers: Stories of the First Circumnavigation. “But I believe he very well could have been the first person to circumnavigate the globe.”

Enrique’s story begins a decade prior to the famed expedition in 1511, when the Portuguese first raided Malaysia and sacked the capital at the time, Malacca. Magellan, who took part in the violent conquest, captured 11-year-old Enrique as a slave and brought him back to Portugal. When Magellan set sail out of Spain years later, he took Enrique with him to serve as an interpreter.

The expedition originally intended to find an alternate western route to the Spice Islands, because the eastern routes were largely controlled by the Portuguese. But the journey was rough: The western way was longer than anticipated, and disaster struck again and again, with much of the crew succumbing to scurvy and hunger around South America. When the ship reached the Philippines after two years, Magellan was killed by a poisoned arrow during battle in Mactan.

Days after Magellan’s death, another calamity occurred, when the crew was ambushed in Cebu, another Filipino province. Antonio Pigafetta, an Italian scholar and one of few survivors of the expedition, claimed that the ambush was orchestrated by Enrique, writing in his diary:

Our interpreter would not go ashore for the things which we required. Duarte Barbosa, the commander of the ship, told him that though his master was dead, he had not become free on that account. At the same time he threatened to have him flogged, if he did not go on shore quickly, and do what was wanted for the service of the ships.

Magellan’s will stipulated that Enrique should be freed upon his death, but from Pigafetta’s writings, it was evident the fellow crew members did not honor that request or possibly didn’t know about it. Enrique obliged, and then things got complicated.

The slave rose up, and did as though he did not care much for these threats; and having gone on shore, he informed the Christian king that we were thinking of going away soon, but that if he would follow his [Enrique’s] advice, he might become master of all our goods and of the ships themselves. The King of Zubu [Cebu] listened favorably to him, and they arranged to betray us.

At a banquet with King Humabon of Cebu, the expedition members were massacred, and few survived. “But Enrique’s betrayal is complete speculation on Pigafetta’s part,” explains Sailors.

What is evident was that Enrique was ashore during the massacre. The following is the last line in the historical record about Enrique, which occurred when the crew members who had remained upon the ship yelled to a bloodied fellow member on shore.

“We asked him what had become of his companions and the interpreter, and he said that all had been slain except the interpreter.” The expedition then frantically set sail from Cebu, leaving Enrique and the wounded man behind.

On his last known day in history, Enrique was alive on the island of Cebu, around 1,200 miles (2,000 kilometers) from his native Malacca. Meanwhile, the Spanish expedition was around 9,000 miles (15,000 kilometers) away from returning home. This is where historians wonder: Did Enrique make it home first, or did he even make it at all? The answer to that question would make all the historical difference. After all, Enrique is the first person documented in history who went from Malaysia to Spain to South America before landing again in Southeast Asia, last seen in the Philippines. For Enrique, an enslaved man, it was a long, ten-year journey.

According to Sailors, we can at least say Enrique was the first person to circumnavigate the globe linguistically. He had come full circle to a place where his native Malay tongue was spoken, as it was the language of trade in the region. The question now is: Was it just a linguistic circumnavigation, or did he go all the way?

“Enrique finally had a chance to go home; if I was him, I would’ve done anything necessary to get there,” said Sailors. “At the time, Cebu was at the crossroads of multiple Siamese and Chinese trade networks. It would’ve been relatively easy for Enrique to jump on a ship to get home to Malacca.”

“I would’ve gone home,” echoed Osman. “There’s also evidence there was a Siamese trader at the first meeting with the King of Cebu, and he may have taken Enrique back to Malacca.”

Enrique’s role—and his position in history—is difficult to precisely pin down. His narrative is shrouded in inconsistencies, dead-ends in the historical record, and only occasional mentions in other people’s stories. No documents produced yet can definitively prove the claim. But the story has captivated the people of Malaysia, Indonesia, and Philippines all the same, all who proudly uphold Enrique as part of their story and a hero to honor. Multiple people in all three nations have come forward claiming to be one of his descendants, and Osman interviewed them as part of the memorial project, despite expressing skepticism over the validity of some of those claims.

As much as history is set in stone, some of it is still up for debate, interpretation, and reinterpretation from new perspectives, especially as it pertains to the forgotten legacy and achievements of those who were enslaved.

That’s what Sailors and Osman are working to preserve, “to highlight a figure lost to history,” as Osman says. “[My work] opened up quite a lot of people to a history they’ve never been taught about in school,” he continues. “Besides, if history is always written by the victors, how true can it be?”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook