Flying Circuses Led to the First Aerial Maps of Earth

There was vomiting, crashes, fire, and an abandoned cat.

On September 8, 1785, Thomas Baldwin saw something nobody had ever seen before: the English city of Chester and its surroundings from above. And then he did something nobody had ever done before: He produced maps of what he saw—the very first aerial maps in history. They’re included in Airopaidia, a curious book that devotes hundreds of pages to Baldwin’s one and only balloon trip.

People have been flying planes for 117 years. But the history of human flight goes back another 120 years before the Wright Brothers’ first airplane ride at Kitty Hawk. On November 21, 1783, a balloon manufactured by the Montgolfier brothers took off near Paris, transporting two passengers 5.5 miles through the air in 25 minutes.

Balloonapalooza

Almost immediately, the first manned flight set off a “balloon craze” throughout Europe. Balloonists traveled from city to city, attracting large crowds with their “flying circuses” (hence, the term well-known to Monty Python fans). The novel apparitions caused some to faint, others to vomit. Destruction and rioting were not uncommon.

Certainly spectacular, ballooning itself was not without danger. Pilâtre de Rozier, one of the two passengers on the first montgolfière, died in June 1785 while attempting to cross the English Channel, when his balloon caught fire.

Lamenting the “balloonomania” of his day, novelist Horace Walpole complained that “all our views are directed to the air; balloons occupy senators, philosophers, ladies, everybody.” He hoped that these “new mechanic meteors” would not be “converted into new engines of destruction to the human race, as is so often the case of refinements or discoveries in science.”

The first British balloonist was a remarkable Scotsman named James Tytler, who on 27 August 1784 managed a 10-minute flight in a hot air balloon just outside Edinburgh.

A jack of all trades, Tytler was also a pharmacist, surgeon, printer, poet, pamphleteer, and editor of the second edition of the Encyclopædia Britannica. Less tastefully, he was the anonymous author of Ranger’s Impartial List of the Ladies of Pleasure in Edinburgh, a review of 66 of the city’s prostitutes.

Tytler’s ballooning exploits fizzled out, and he was soon overshadowed by the flamboyant Vincenzo Lunardi, the “Daredevil Aeronaut.”

The Daredevil Aeronaut

On September 15, 1784—hardly a month after Tytler—Lunardi took off from the Artillery Ground in Finsbury on the first balloon flight in England. In attendance were the Prince of Wales and 200,000 other Londoners.

Lunardi was accompanied by a dog, cat, and caged pigeon. Flying north, he briefly touched down at Welham Green in a place still called “Balloon Corner.” There, he released the cat, as he thought it had become unwell from the cold. Minus the feline, Lunardi took off again. England’s first manned flight came to an end in a field near Standon Green End, 24 miles north of Finsbury. A memorial stone still marks the spot.

The next year, Lunardi toured England and Scotland with his Grand Air Balloon, drawing large crowds everywhere. Many of his flights were spectacular but not all were a success. On one of his Scottish flights, he drifted off over the North Sea and crashed into the waves. He was only rescued thanks to a passing fishing boat.

On September 8, Lunardi’s flying circus arrived in Chester, and here, Thomas Baldwin enters the play. Baldwin was a local clergyman’s son and sometime curate himself. He was more interested in science than religion, though, and had lately gone completely balloon-crazy. In December of the previous year, he had proposed building a “Grand Naval Air-balloon,” complete with sails, oars, and a rudder. Nothing came of it.

Nevertheless, Baldwin had a healthy belief in his own relevance for the ballooning industry. He in fact contended, at one point, that French balloonists had stolen his ideas and that “montgolfières,” as hot-air balloons were then called, should rightly be known as “baldwins.”

Baldwin’s flight

Before his take-off in Chester, Lunardi burned himself on the acid used to make the hydrogen for the balloon. Because of his injury, he couldn’t make the ascent himself, so he agreed to rent out his Grand Air Balloon to Baldwin instead. And with that unbelievable stroke of luck, Baldwin lifted off from Chester Castle at 1:40 p.m. on September 8, 1785, for his first (and only) trip between the clouds. The new-fangled aeronaut certainly came well equipped. Baldwin brought tools for writing and sketching, a speaking trumpet, half a mile of twine, a hardboard map (which could also serve as a table), and—as apparently was de rigueur among balloonists—a pigeon.

Once aloft, Baldwin conducted several experiments. He used inflated bladders to get a sense of differences in air pressure, and he sampled various foods to find out whether they would taste differently high up in the air. (They did not, despite testimonials to the contrary reported from “the Peak of Tenerife” in Spain.)

Toward the end of his journey, Baldwin was forced to climb up on the rigging of the balloon to fix a stuck valve to release gas so he could descend. The balloon eventually came down at Belleair Farm in Rixton, 25 miles northeast of Chester, seven minutes shy of 4 p.m.

After barely two hours in the air, Baldwin is a man transformed. He sets down his experiences in Airopaidia, which is published the next year. Filling out 362 pages, it’s as much a gushing eyewitness report as it is a detailed scientific account of his trip—plus advice to future “aeronauts.”

Much to his chagrin, not much has been made of Baldwin’s contributions to ballooning. Yet this one-shot amateur did produce a few firsts.

The first true aerial maps

He appears to have been the first to observe the “pilot’s glory,” a halo that appears around the shadow of a person’s head. This is the result of sunlight refracting on tiny water droplets in the atmosphere.

He was also the first to map out what he saw from a balloon. Bird’s eye perspectives were nothing new in cartography. Mapmakers often represented cities from elevated perspectives in order to better show the layout of streets, for example. Leonardo da Vinci even pioneered the “satellite view,” drawing a plan of the city of Imola in 1502 as if from straight above.

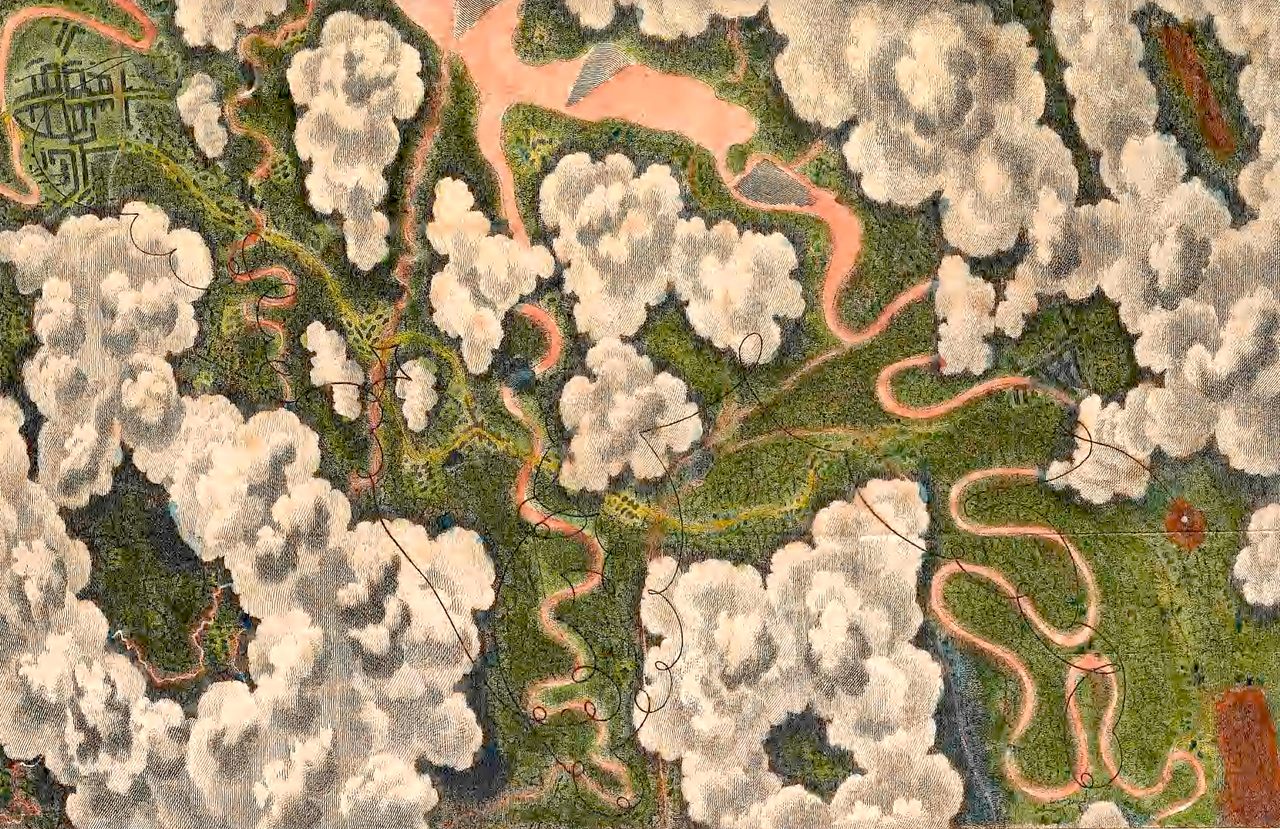

These, however, were works of the imagination. Baldwin’s maps were the first aerial maps made from actual observation. And here, the maps say more than a thousand words could. Lunardi, when he observed London from above, had to admit: “I can find no simile to convey an idea of it.”

Baldwin included three maps, two of which were colored, in Airopaidia:

- A circular view of Chester, as observed from the balloon’s greatest elevation.

- A “Specimen of Balloon Geography,” showing the area between Chester and Warrington from above the clouds.

- The balloon over Helsby-Hill in Cheshire.

Baldwin even gave his readers specific instructions on how to enjoy his maps to the fullest: roll up a piece of paper and peer over them as if through a telescope. For Baldwin and his fellow balloonists, flight among the clouds represented the height—quite literally—of the “Sublime,” a Romantic notion that married the aesthetic to the ecstatic.

As he related on pp. 37-38 of Airopaidia:

But what Scenes of Grandeur and Beauty!

A Tear of pure Delight flaſhed in his Eye! Of pure and exquiſite Delight and Rapture; to look down on the unexpected Change already wrought in the Works of Art and Nature, contracted to a Span by the NEW PERSPECTIVE, diminiſhed almoſt beyond the Bounds of Credibility.

Yet ſo far were the Objects from loſing their Beauty, that EACH WAS BROUGHT UP in a new Manner to the Eye, and diſtinguiſhed by a Strength of Colouring, a Neatneſs and Elegance of Boundary, above Descriptions charming!

The endleſs Variety of Objects, minute, distinct and ſeparate, tho’ apparently on the ſame Plain or Level, at once ſtriking the Eye without a Change of its Position, aſtoniſhed and enchanted. Their Beauty was unparalleled. The Imagination itſelf was more than gratified; it was overwhelmed.

The gay Scene was Fairy-Land, and Cheſter Lilliput.

He tried his Voice and ſhouted for Joy. His Voice was unknown to himſelf, ſhrill and feeble. There was no Echo.

A popped balloon

Toward the end of the decade, the ballooning craze died down. Following a deadly accident involving an onlooker in 1786, Lunardi left Britain for Italy, Spain, and Portugal. At the mercy of the winds, balloons lacked any obvious practical application, military or otherwise. And with the outbreak of the French Revolution in 1789, Europe had enough to occupy its attention for the next quarter century. According to one compiler, by 1836, no more than 313 people had taken to the skies in England.

By then, the flying circuses were things of the past. Baldwin died in 1804, never having flown again. But the excitement of those days still gushes from his Airopaidia, and the maps it contains remain a unique milestone in the history of ballooning—and cartography.

View the entire Airopaidia on the Internet Archive.

This article originally appeared on Big Think, home of the brightest minds and biggest ideas of all time. Sign up for Big Think’s newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook