The Atlas Excerpt: Banvard’s Folly

An Illustration showing John Banvard presenting his panorama to Queen Victoria at Windsor Castle, 1849 (Photo: Courtesy Erkki Huhtamo, ‘Illusions in Motion: Media Archaeology of the Moving Panorama and Related Spectacles’, The MIT Press)

An Illustration showing John Banvard presenting his panorama to Queen Victoria at Windsor Castle, 1849 (Photo: Courtesy Erkki Huhtamo, ‘Illusions in Motion: Media Archaeology of the Moving Panorama and Related Spectacles’, The MIT Press)

EDITOR’S NOTE: Each month, we’ll be sharing our enthusiasm for a book of recent or not-so-recent vintage that touches on Atlas Obscura’s central theme: the profound strangeness of our world. Our first installment of the Atlas Excerpt comes from a book I love dearly, Paul Collins’ Banvard’s Folly: Thirteen Tales of People Who Didn’t Change the World. Published in 2001, it’s a collection of portraits of some of history’s most wonderfully misguided (and forgotten) artists, inventors, and entrepreneurs. The title essay tells the story of America’s first millionaire artist, John Banvard, whose three-mile-long scrolling panorama of the Mississippi River was once once of the most famous paintings in the world. —Joshua Foer

Mister Banvard has done more to elevate the taste for fine arts, among those who little thought on these subjects, than any single artist since the discovery of painting and much praise is due him. —The Times of London

The life of John Banvard is the most perfect crystallization of loss imaginable. In the 1850’s, Banvard was the most famous living painter in the world, and possibly the first millionaire artist in history. Acclaimed by millions and by such contemporaries as Dickens, Longfellow, and Queen Victoria, his artistry, wealth, and stature all seemed unassailable. Thirty-five years later, he was laid to rest in a pauper’s grave in a lonely frontier town in the Dakota Territory. His most famous works were destroyed, and an examination of reference books will not turn up a single mention of his name. John Banvard, the greatest artist of his time, has been utterly obliterated by history.

What happened?

In 1830, a fifteen-year-old American schoolboy passed out this handbill to his classmates, complete with its homely omission of a 5th entertainment:

BANVARD’S ENTERTAINMENTS (to be seen at No. 68 Centre street, between White and Walker.) Consisting of 1/. Solar Microscope 2nd. Camera Obscura 3rd. Punch and Judy 4th. Sea Scene 6th. Magic Lantern Admittance (to see the whole) six cents. The following are the days of performance, viz: Mondays, Thursdays, and Saturdays. Performance to commence at half-past 3 P.m. JOHN BANVARD, Proprietor

Although his classmates were not to know, they were only the first of more than two million to witness the showmanship of John Banvard. Visiting Banvard’s home museum and diorama in Manhattan, they might have been greeted by his father, Daniel, a successful building contractor and a dabbler in art himself. His adventurous son had acquired a taste for sketching, writing, and science–the latter pursuit beginning with a bang when an experiment with hydrogen exploded in the young man’s face, badly injuring his eyes.

Worse calamities lay in store. When Daniel Banvard suffered a stroke in 1831, his business partner fled with the firm’s assets. Daniel’s subsequent death left the family bankrupt. After watching his family’s possessions auctioned off, John lit out for the territories–or at least for Kentucky. Taking up residence in Louisville as a drugstore clerk, he honed his artistic skills by drawing chalk caricatures of customers in the back of the store. His boss, not interested in patronizing adolescent art, fired him. Banvard soon found himself scrounging for signposting and portrait jobs on the docks.

It was here that he met William Chapman, the owner of the country’s first showboat. Chapman offered Banvard work as a scene painter. The craft itself was primitive by the standards of later showboats, as Banvard later recalled:

The boat was not very large, and if the audience collected too much on one side, the water would intrude over the low gunwales into their exhibition room. This kept the company by turns in the un-artist-like employment of pumping, to keep the boat from sinking. Sometimes the swells from a passing steamer would cause the water to rush through the cracks of the weather-boarding, and give the audience a bathing .... They made no extra charge for this part of the exhibition.

The pay proved to be equally unpredictable. But if nothing else, Chapman’s showboat gave Banvard ample practice in the rapid sketching and painting of vast scenery–a skill that would eventually prove to be invaluable.

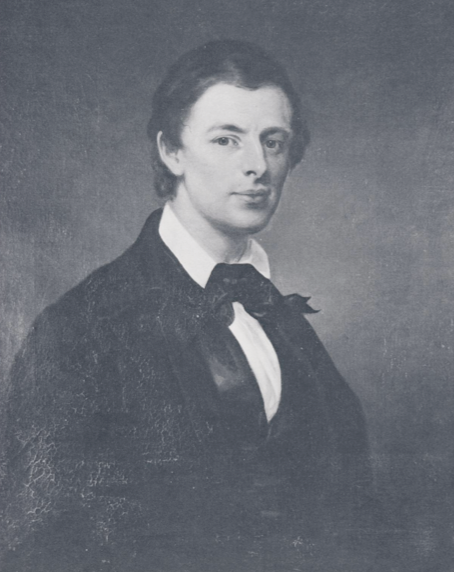

A portrait of John Banvard by Anna Mary Howitt, 1849 (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

Deciding that he’d rather starve on his own payroll than on someone else’s, Banvard left the following season. He disembarked in New Harmony, Ohio, where he set about assembling a theater company. Banvard himself would serve as an actor, scene painter, and director; occasionally, he’d dash onstage to perform as a magician. He funded the venture by suckering a backer out of his life savings; this pattern of arts financing would haunt him later in life.

The river back then was still unspoiled—and unsafe. But the troupe did last for two seasons, performing Shakespeare and popular plays while they floated from port to port. Few towns could support their own theater, but they could afford to splurge when the floating dramatists tied up at the dock. Customers sometimes bartered their way aboard with chickens and sacks of potatoes, and this helped fill in the many gaps in the troupe’s menu. But eventually food, money, and tempers ran so short that Banvard, broke and exhausted from bouts with malarial ague, was reduced to begging on the docks of Paducah, Kentucky. While Banvard was now a toughened showman with several years of experience, he was also still a bright, intelligent, and sympathetic teenager. A local impresario took pity on the bedraggled boy and hired him as a scene painter. Banvard, relieved, quit the showboat.

It was a good thing that he did quit, for farther downriver a bloody knife fight broke out between the desperate thespians. The law showed up in the form of a hapless constable, who promptly stumbled through a trapdoor in the stage and died of a broken neck. With a dead cop on their hands, the company panicked and abandoned ship; Banvard never heard from any of them again.

While in Paducah, Banvard made his first attempts at crafting “moving panoramas.” The panorama–a circular artwork that surrounded the viewer–was a relatively new invention, a clever use of perspective that emerged in the late 1700’s. By 1800, it was declared an official art form by the Institut de France. Photographic inventor L. J. Daguerre went on to pioneer the “diorama,” which was a panorama of moving canvas panels viewed through atmospheric effects. When Banvard was growing up in Manhattan, he could gape at these continuous rolls of painted canvas depicting seaports and “A Trip to Niagara Falls.”

View of a Daguerre diorama, c. 1869 (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

Moving into his twenties with the memories of his years of desperate illness and hunger behind him, Banvard spent his spare time in Paducah painting landscapes and creating his own moving panoramas of Venice and Jerusalem. Stretched between two rollers and operated on one side by a crank, they allowed audiences to stand in front and watch exotic scenery roll by. Banvard could not stay away from the river for long, though. He began plying the Mississippi, Ohio, and Missouri rivers again, working as a dry-goods trader and an itinerant painter. He also had his eye on greater projects: a diorama of the “infernal regions” had been touring the frontier successfully, and Banvard thought he could improve upon it. During a stint in Louisville, he executed a moving panorama that he described as “INFERNAL REGIONS, nearly 100 feet in length.” He completed and sold this in 1841, and it came as a crowning success atop the sale of his Venice and Jerusalem panoramas.

It is not easy to imagine the effect that panoramas had upon their viewers. It was the birth of motion pictures–the first true marriage of the reality of vision with the reality of physical movement. The public was enthralled, and so was Banvard: he had the heady rush of an artist working at the dawn of a new media. Emboldened by his early successes, the twenty-seven-year-old painter began preparations for a painting so enormous and so absurdly ambitious that it would dwarf any attempted before or since: a portrait of the Mississippi River.

When we read of the frontier today, we are apt to envision California and Nevada. In Banvard’s time, though, “the frontier” still meant the Mississippi River. A man setting off into its wilds and tributaries would only occasionally find the friendly respite of a town; in between he faced exposure, mosquitoes, and, if he ventured ashore, bears. But Banvard had been up and down the river many times now, and had taken at least one trip solo as a traveling salesman. The idylls of river life had charms and hazards, as he later recalled:

All the toil, and its dangers, and exposure, and moving accidents of this long and perilous voyage, are hidden, however, from the inhabitants, who contemplate the boats floating by their dwellings and beautiful spring mornings, when the verdant forest, the mild and delicious temperature of the air, the delightful azure of the sky of this country, the fine bottom on one hand, and the romantic bluff on the other, the broad and the smooth stream rolling calmly down the forest, and floating the boat gently forward, present delightful images and associations to the beholders. At this time, there is no visible danger, or call for labor. The boat takes care of itself; and little do the beholders imagine, how different a scene may be presented in half an hour. Meantime, one of the hands scrapes a violin, and others dance. Greetings, or rude defiances, or trials of wit, or proffers of love to the girls on shore, or saucy messages, are scattered between them and the spectators along the banks.

Banvard knew the physical challenge that he faced and was prepared for it. But the challenge to his artistry was scarcely imaginable. In the spring of 1842, after buying a skiff, provisions, and a portmanteau full of pencils and sketch pads, he set off down the Mississippi River. His goal was to sketch the river from St. Louis all the way to New Orleans.

For the next two years, he spent his nights with his portmanteau as a pillow, and his days gliding down the river, filling his sketch pads with river views. Occasionally he’d pull into port to hawk cigars, meats, household goods, and anything else he could sell to river folk. Banvard prospered at this, at one point trading up to a larger boat so as to sell more goods. Recalling those days to audiences a few years later–exercising his flair for drama, of course, and referring to himself in the third person–he remembered the trying times in between, when he was alone on the river:

His hands became hardened with constantly plying the oars, and his skin as tawny as an Indian’s, from exposure to the sun and the vicissitudes of the weather. He would be weeks altogether without speaking to a human being, having no other company than his rifle, which furnished him with his meat from the game of the woods or the fowl of the river .... In the latter part of the summer he reached New Orleans. The yellow fever was raging in that city, but unmindful of that, he made his drawing of the place. The sun the while was so intensely hot, that his skin became so burnt that it peeled from off the back of his hands, and from his face. His eyes became inflamed by such constant and extraordinary efforts, from which unhappy effects he has not recovered to this day.

But in his unpublished autobiography, he recalled his travels a bit more benignly:

[The river’s current was] averaging from four to six miles per hour. So I made fair progress along down the stream and began to fill my portfolio with sketches of the river shores. At first it appeared lonesome to me drifting all day in my little boat, but I finally got used to this.

By the time he arrived back in Louisville in 1844, this adventurer had acquired the sketches, the tall tales, and the funds to realize his fantastic vision of the river he had traveled. It would be the largest painting the world had ever known.

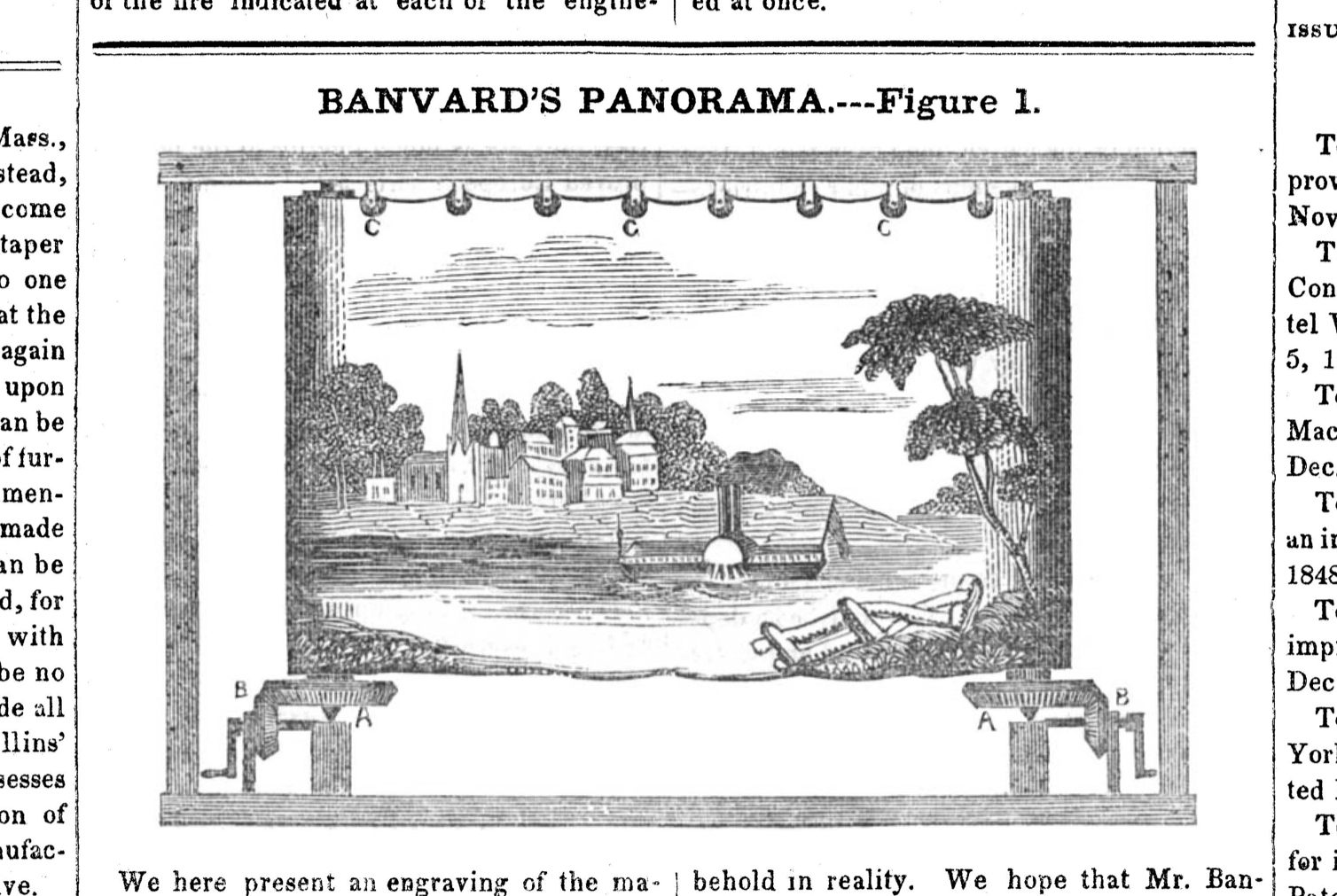

An excerpt from the Scientific American, 16 December 1848 (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

An excerpt from the Scientific American, 16 December 1848 (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

Banvard was attempting to paint three thousand miles of the Mississippi from its Missouri and Ohio sources. But if his project was grander than any before, so were the ambitions of his era. Ralph Waldo Emerson, working the New England public lecture circuit, had already lamented, “Our fisheries, our Negroes, and Indians, our boasts … the northern trade, the southern planting, the Western clearing, Oregon, and Texas, are yet unsung. Yet America is a poem in our eyes, its ample geography dazzles the imagination ....” The idea had been voiced by novelists like Cooper before him, and later on by such poets as Walt Whitman. When Banvard built a barn on the outskirts of Louisville in 1844 to house the huge bolts of canvas that he had custom-ordered, he was sharing in this grand vision of American art.

His first step was to devise a tracked system of grommets to keep the huge panorama canvas from sagging. It was ingenious enough to be patented and featured in a Scientific American article a few years later. And then, for month after month, Banvard worked feverishly on his creation, painting in broad strokes: trained in background painting, he specialized in conveying the impression of vast landscapes. Looked at closely, this work held little for the connoisseur trained in conventions of detail and perspective. But motion worked magic upon the rough-hewn cabins, muddy banks, blooming cottonwoods, frontier towns, and medicine-show flatboats.

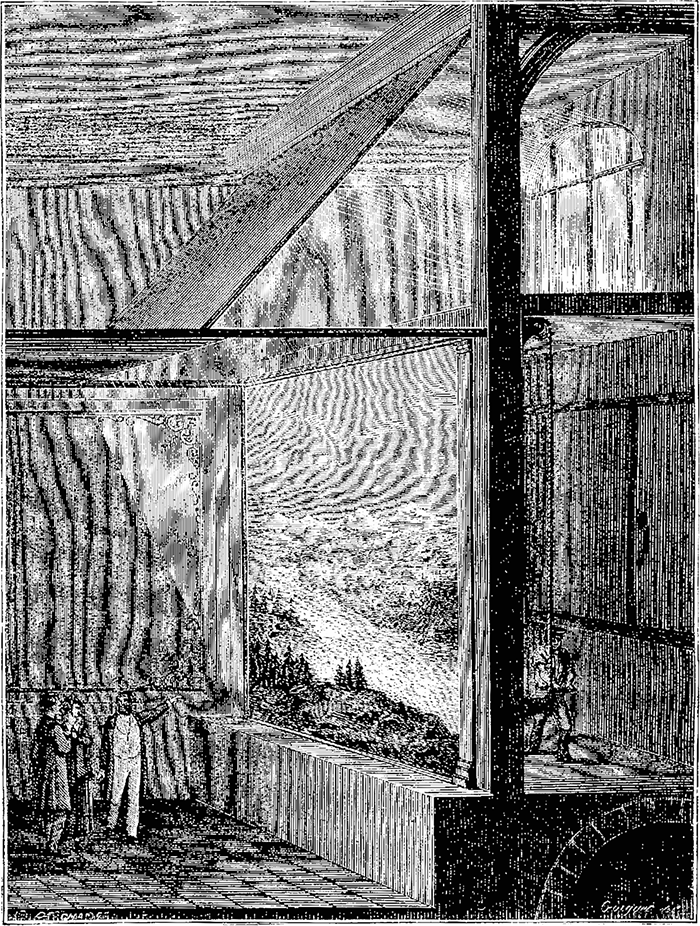

During this time he also worked in town on odd jobs, but if he told anyone of his own painting, we have no record of it. Fortunately, though, we have a letter from an unexpected visitor to Banvard’s barn. Lieutenant Selin Woodworth had grown up a few houses away from Banvard and hadn’t seen him in sixteen years, and he could hardly pass by in the vast frontier without saying hello. When he showed up unannounced at the barn, he was amazed by what maturity had wrought in his childhood friend:

I called at the artist’s studio, an immense wooden building .... The artist himself, in his working cap and blouse, pallet and pencil in hand, came to the door to admit us .... Within the studio, all seemed chaos and confusion, but the life-like and natural appearance of a portion of his great picture, displayed on one of the walls in a yet unfinished state .... A portion of this canvas was wound upon a upright roller, or drum, standing on one end of the building, and as the artist completes his painting he thus disposes of it.

Any description of this gigantic undertaking … would convey but a faint idea of what it will be when completed. The remarkable truthfulness of the minutest objects upon the shores of the rivers, independent of the masterly, and artistical execution of the work will make it the most valuable historical painting in the world, and unequaled for magnitude and variety of interest, by any work that has been heard of since the art of painting was discovered.

This was the creation that Banvard was ready to unveil to the world.

Banvard approached his opening day with the highest of hopes. Residents reading the Louisville Morning Courier discovered on June 29, 1846, that their local painter had rented out a hall to show off his work: “Banvard’s Grand Moving Panorama of the Mississippi will open at the Apollo Rooms, on Monday Evening, June 29, 1846, and continue every evening till Saturday, July 4.” A review in the same paper declared, “The great three-mile painting is destined to be one of the most celebrated paintings of the age.” Little did the writer of this review know how true this first glimpse was to prove: for while it was to be the most celebrated painting of the age, it did not last for the ages.

Opening night certainly proved to be inauspicious. Banvard paced around his exhibition hall, waiting for the crowds and the fifty-cent admission fees to come pouring in. Darkness slowly fell, and a rain settled in. The panorama stood upon the lighted stage, fully wound and awaiting the first turn of the crank. And as the sun set and rain drummed on the roof, John Banvard waited and waited.

Not a single person showed up.

It was a humiliating debut, and it should have been enough to make him pack up and leave. But the next day saw John Banvard move from being a genius of artistry to a genius of promotion. He spent the morning of the 30th working the Louisville docks, chatting to steamboat crews with the assured air of one who’d navigated the river many times himself. Moving from boat to boat, he passed out free tickets to a special afternoon matinee.

Even if they had paid the full fee, the sailors would have got their money’s worth that afternoon. As the painted landscape glided by behind him, Banvard described his travels upon the river-a tall tale of pirates, colorful frontier eccentrics, hairbreadth escapes, and wondrous vistas, a tad exaggerated, perhaps, but it still convinced a hallful of sailors who could have punctured his veracity with a single catcall. When he gave his evening performance, crew recommendations to passengers boosted his take to $10—not bad for an evening’s work in 1846. With each performance the audience grew, and within a few days he was playing to a packed house.

Flush with money and a successful debut, Banvard returned to his studio and added more sections to the painting, and then he moved it to a larger venue. The crowds continued to pour in, and nearby towns chartered steamboats to see the show. With the added sections, the show stretched to over two hours in length; the canvas would be cranked faster or slower depending on audience response. Each performance was unique, even for a customer who sat through two in a row. The canvas wasn’t rewound at the end of the show, so the performances alternated between upriver and downriver journeys.

After a successful shakedown cruise, Banvard was ready to take his “Three Mile Painting” to the big city. He held his last Louisville show on October 31 and then headed for the epicenter of American intellectual culture: Boston.

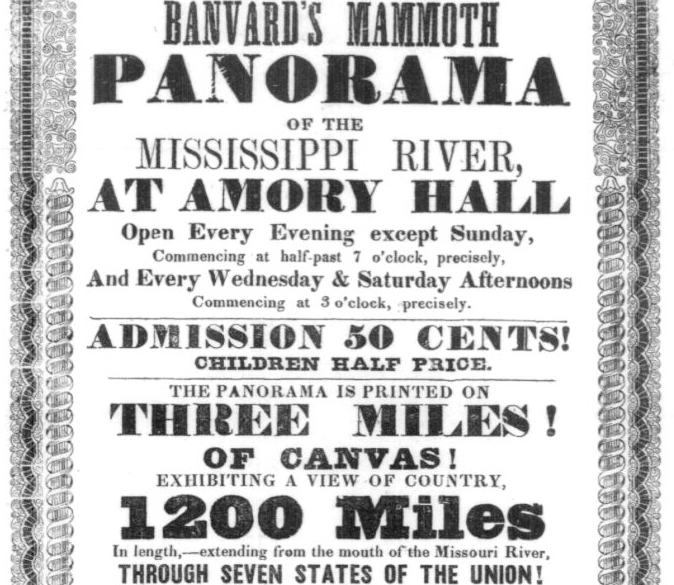

Banvard installed his panorama in Boston’s Armory Hall in time for the Christmas season. He had honed his delivery to a perfect blend of racy improvisation, reminiscences, and tall tales about infamous frontier brigands. The crank machinery was now hidden from the audience, and Banvard had commissioned a series of piano waltzes by Thomas Bricher to accompany his narration. With creative lighting and the unfurling American landscape behind him, Banvard had created a seemingly perfect synthesis of media.

Detail of advertisement for performance by John Banvard at Boston’s Amory Hall, 1847 (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

Audiences loved it. By Banvard’s account, in six months 251,702 Bostonians viewed his extraordinary show; at fifty cents a head, he’d made about $100,000 in clear profit. In just one year, he’d gone from modest frontier sign painter to famous and wealthy man–and probably the country’s richest artist. When he published the biographical pamphlet Description of Banvard’s Panorama of the

Mississippi River (1847) and a transcription of his show’s music, The Mississippi Waltzes, he made more money. But there was an even happier result to his inclusion of piano music–the young pianist he’d hired to perform it, Elizabeth Goodman, soon became his fiancee, and then his wife.

Accolades continued to pour in, culminating in a final Boston performance that saw the governor, the speaker of the house, and state representatives in the audience unanimously passing a resolution to honor Banvard. His success was also the talk of Boston’s intellectual elite. John Greenleaf Whittier titled a book after it (The Panorama and Other Poems) in 1856, and Henry Wadsworth Longfellow wrote about the Mississippi in his epic Evangeline after seeing one of Banvard’s first Boston performances. Longfellow had never seen the river himself–to him, the painting was real enough to suffice. In fact, Longfellow was to invoke Banvard again in his novel Kavanaugh, using him as the standard by which future American literature was to be judged: “We want a national epic that shall correspond to the size of the country; that shall be to all other epics what Banvard’s panorama of the Mississippi is to all other paintings–the largest in the world.”

There is little doubt that Banvard’s “Three Mile Painting” was the longest ever produced. But it was a misleading appellation. John Hanners –the scholar who almost single-handedly has kept Banvard’s memory alive in our time–points out: “Banvard always carefully pointed out that others called it three miles of canvas. … The area in its original form was 15,840 square feet, not three miles in linear measurement.”

But perhaps Banvard was in no hurry to correct the public’s inflated perceptions of his painting. His fame was now preceding him, and he moved his show to New York City in 1847 to even bigger crowds and greater enrichment; it was hailed there as “a monument of native talent and American genius.” Each night’s receipts were carted to the bank in locked strongboxes; rather than count the massive deposits, the banks simply started weighing Banvard’s haul.

With acclaim and riches came the less sincere flattery of his fellow artists. The artist closest upon Banvard’s heels was John Rowson Smith, who had painted a supposed “Four Mile Painting.” For all Banvard’s tendencies toward exaggeration, there is even less reason or evidence to believe that his opportunistic rivals produced panoramas larger than his. Still, it was a worrisome trend. Banvard had been hearing for some time of plans by unscrupulous promoters to copy his painting and to then show the pirated work in Europe as the “genuine Banvard panorama.” With the United States success behind him, Banvard closed his New York show and booked a passage to Liverpool.

Banvard spent the summer of 1848 warming up for his London shows with short runs in Liverpool, Manchester, and other smaller cities. In London, the enormous Egyptian Hall was booked for his show. He began by suitably impressing the denizens of Fleet Street papers with a special showing. “It is impossible,” the Morning Advertiser marveled, “to convey an adequate idea of this magnificent [exhibition].” The London Observer was equally impressed in its review of November 27, 1848: “This is truly an extraordinary work. We have never seen a work … so grand in its whole character.” Banvard was rapidly achieving a sort of artistic beatification in the press.

The crowds and the money flowed in yet again. But to truly bring in the chattering classes, Banvard needed something that he’d never had in the United States: the imprimatur of royalty. After much finagling and plotting by Banvard, he was summoned to Windsor Castle on April 11, 1849, for a special performance before Queen Victoria and the royal family. Banvard was already a rich man, but royal approval could make the difference between being a mere artistic showman and an officially respected painter. Banvard gave the performance of his life, delivering his anecdotes in perfect combination with his wife at the piano; at the end, when he gave his final bow to the family assembled at St. George’s Hall, Banvard knew that he had made it as an artist. For the rest of his life, he was to look back upon this as his finest hour.

His panorama show was now a sensation, running for a solid twenty months in London and drawing more than 600,000 spectators. An enlarged and embellished reprint of his autobiographical pamphlet, now titled Banvard, or the Adventures of an Artist (1849), also sold well to Londoners, and his show’s waltzes could be heard in many a parlor. He penetrated every level of society; after attending one show, Charles Dickens wrote him in an admiring letter: “I was in the highest degree interested and pleased by your picture.” To the other dwellers of this island nation, whose experience of sailing was often that of stormy seas, Banvard offered the spice of frontier danger blended with the honeyed idylls of riverboat life:

Certainly, there can be no comparison between the comfort of the passage from Cincinnati to New Orleans in such a steamboat, and to a voyage at sea. The barren and boundless expanse of waters soon tires upon every eye but a seaman’s. And then there are storms, and the necessity of fastening the tables, and of holding onto something, to keep in bed. There is the insupportable nausea of sea sickness, and there is danger. Here you are always near the shore, always see green earth; can always eat, write and study, undisturbed. You can always obtain cream, fowls, vegetables, fruit, fresh meat, and wild game, in their season, from the shore.

Toward the end of these London shows, Banvard found himself increasingly dogged by imitators–there were fifty competing panoramas in the 1849-50 season alone. In addition to suffering competition from longtime rival John Rowson Smith, Banvard now had scurrilous accusations of plagiarism flung at him by fellow expatriate portraitist George Caitlin, a jealous painter who had “befriended” Banvard in order to borrow money. Banvard also found his shows being set upon by the spies of his rivals, who hired art students to sit in the audience and sketch his work as it rolled by.

We know that a form of art has permeated a culture when cheap imitations appear, and even more so when parodies of these imitations emerge. There is a long-forgotten work in this vein by American humorist Artemus Ward, which was published posthumously as Artemus Ward, His Panorama (1869). Ward spent the last years of his life working in London, and had probably attended some of the numerous panoramic travelogues and travesties that darted about in Banvard’s wake. His panorama, as shown by illustrations of the supposed stage (which, as often as not, is obscured by a faulty curtain), consists of a discourse on San Francisco and Salt Lake City, often interrupted by crapulous bits of tangential mumbling in small type:

If you should be dissatisfied with anything here tonight-I will admit you all free in New Zealand—if you will come to me there for the orders.

This story hasn’t anything to do with my Entertainment, I know—but one of the principle features of my Entertainment is that it contains so many things that don’t have anything to do with it.

For ads reproduced in the book, Ward munificently assures his audiences that his lecture hall has been lavishly equipped with “new doorknobs.” But Banvard’s most serious rivals were not such bumblers, and so he had to swing back into action. Locking himself in the studio again, he created another Mississippi panorama. Where the first panorama had been a view of the eastern bank, this new painting depicted the western bank. He then placed the London show in the hands of a new narrator and toured Britain himself with the second painting for two years, bringing in nearly 100,000 more viewers.

What might Banvard have done with these two paintings had he placed them onstage together? Angled in diagonally from each side to terminate just behind the podium, moving in unison, they would have provided a sort of stereoptical effect of floating down the center of the Mississippi River. It would have been the first “surround multimedia.” For all of Banvard’s innovation, though, there is no record of such an experiment.

Not all of Banvard’s time in London was spent on his own art. In his spare hours, he haunted the Royal Museum; he was fascinated by its massive collection of Egyptian artifacts. He soon became a protege of the resident Egyptologists, and under their tutelage he learned to decipher hieroglyphics—the only American of his time, by some accounts, to learn this skill. For decades afterward, he was able to pull sizable crowds to his lectures on the reading of hieroglyphics.

Banvard moved his show to Paris, where his success continued unabated for another two years. He was now also a family man: a daughter, Gertrude, was born in London, and a son, John Jr., was born in Paris. Having children scarcely slowed down his travels; on the contrary, he left the family to spend the next year on an artistic pilgrimage to the Holy Land. In a reprise of his American journey, he sailed down the Nile and filled up notebooks with sketches. But he no longer had to sleep with these notebooks as a pillow. He was now wealthy enough to travel in comfort, and he bought thousands of artifacts along the way-a task assisted by his unusual ability at translating hieroglyphics.

These travels were to become the basis for yet two more panoramas: one of Palestine, and the other of the trip down the Nile. Neither was to earn him as much as his Mississippi panorama; the market was now flooded with imitations, and the public was beginning to weary of the panoramic lecture. Even so, Banvard’s abilities were greater than ever. One American reviewer commented in 1854 in Ballou’s Pictorial Drawing Room Companion:

Mr. Banvard made a name and fortune by his three mile panorama of the Mississippi. It was one of those cases in which contemporary justice is bestowed upon true merit .... His sole teacher in his art is Nature; there are few conventionalisms in his style. His present great work is far superior in artistic merit to his Mississippi–showing his rapid improvement; its effect is enhanced by its great height.

Just eight years after his voyage down the Mississippi, he had become both the most famous living artist in the world and the richest artist in history.

Banvard returned to the United States with his family in the spring of 1852. He was a fantastically wealthy man, so wealthy that he could retire to a castle and casually dabble in the arts for the rest of his life. And at first that’s exactly what he did.

The world’s most famous artist needed an equally imposing home to live in. Accordingly, he bought a sixty-acre lot on Long Island and proceeded to build a replica of Windsor Castle. When the local roads didn’t meet the needs of his castle, he simply built one of his own. He dubbed the castle Glenada in honor of his daughter, Ada; neighbors, who were alternately aghast and awed by the unheard-of construction expenses being incurred, simply dubbed it Banvard’s Folly.

A reporter touring the site was kinder in his appraisal of Banvard’s castle:

It has a magnificent appearance, reminding you forcibly of some of the quaint old castles nestled among the glens of old Scotland. … There are nine offices on the first floor, as you enter from the esplanade, viz., the drawing-room, parlors, conservatory, anteroom, servant’s room, and several chambers. The second story contains the nursery, school-room, guest chambers, bath, library, study, etc., with the servants’ rooms in the towers. The basement is occupied with the offices, store-rooms, etc. Although the facade extends in front one hundred and fifteen feet, still Mr. Banvard says his castle is not completed, as he plans adding a large donjon or keep, to be occupied by his studio, painting-room, and a museum for the reception of the large collection of curiosities which he has gathered in all parts of the world .... it has been proposed to change the name of the place [Cold Spring Harbor] and call it BANVARD ....

Not surprisingly, the residents of the town failed to see the charm of this last proposal.

Still, Banvard spent the next decade in relative prosperity and modest continued artistic success. Indeed, his artistic horizons broadened each year. In 1861, he provided the Union military with his own hydrographic charts of the Mississippi River. General Fremont wrote back personally to thank him for his expert assistance. That same year, Banvard provided the illustration for the first successful chromolithograph in America. The process was unique in duplicating both the color and the canvas texture of the original illustration, which Banvard had titled “The Orison.” The result was a tremendous success and helped assure his continued reputation as a technically innovative artist.

Banvard then turned his attention back to his first love: the theater. Amasis, or, The Last of the Pharaohs was a massively staged “biblical-historical” drama that ran in Boston in 1864. Banvard had both written the play and painted its enormous scenery, and was gratified by its warm reception among critics. It seemed to him that there was nothing that he could not succeed at.

Even as Banvard displayed his Egyptian artifacts to guests at Glenada, the role of museums was changing rapidly in America. By 1780, the “cabinet of wonder” kept by wealthy dilettantes had evolved into the first recognizable museum, operated by Charles Peale in Philadelphia. Joined later by John Scudder’s American Museum in New York, these museums focused on educational lectures and displays–illustrations and examples of unusual natural objects, as well as the occasional memento.

This all changed when P. T. Barnum bought out Scudder’s American Museum in 1841. Barnum brought in a carnivalesque element of equal parts spectacle and half-believable fraud—a potent and highly salable concoction of freak shows, dioramas, magic acts, natural history, and the sheer unrepentant bravado of acts like Tom Thumb and “George Washington’s nursemaid.” Barnum was not an infallible entrepreneur, but he was the shrewdest showman that the country had ever produced. Imitators attracted by Barnum’s success soon found themselves crushed under the weight of Barnum’s one-upmanship and his endless capacity for hyperbolic advertising.

Barnum’s American Museum, New York City, c1858 (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

By 1866, Barnum’s total ticket sales were greater than the country’s population of 35 million. John Banvard, with a castle full of actual artifacts, could scarcely ignore the fortune Barnum was making just a few miles away with objects of much more questionable provenance. Goaded by this, he paid a visit to his old sailing partner William Lillienthal. It had been more than fifteen years since the two had floated down the Nile, collecting the artifacts that now formed the core of Banvard’s collection.

With Lillienthal’s help—and a lot of investors’ money—Banvard was going to take on P. T. Barnum. Their venture was precarious from the start. Aside from the daunting task of challenging America’s greatest showman, Banvard was hampered by his own inexperience. Years of panoramic touring and a successful play had convinced Banvard that he could run a museum, but he had never really run a conventional business with a staff and a building to maintain. In all his years as a showman, he’d earned millions with the help of only one assistant, a secretary whom he eventually fired for stealing a few dollars.

Lillienthal and Banvard financed the “Banvard’s Museum” by floating a stock offering worth $300,000. In lieu of cash, they paid contractors and artisans with shares of this stock; other shares were bought by some of the most prominent families in Manhattan. There was one problem, though: Banvard had never registered his business or its stock with the state of New York. No share certificates existed for the stock. Unbeknownst to Banvard’s backers, and perhaps to Banvard himself, the shares were utterly worthless.

Flush with the money of the unwary, Banvard’s Museum raced toward completion.

When the massive forty-thousand-square-foot building opened on June 17, 1867, it was simply the best museum in Manhattan. The famous Mississippi panorama was onstage in a central auditorium that seated two thousand spectators, and there were a number of smaller lecture rooms and displays of Banvard’s handpicked collection of antiquities. The lecture rooms were important, as Banvard had invited in student groups for free to emphasize the family-friendly educational qualities of his museum, as opposed to Barnum’s sensationalism. The museum also had one genuine crowd-pleaser built right in: ventilation. Poor auditorium ventilation was a constant complaint dogging panoramist shows, and Banvard took the initiative to install louvers and windows all the way around his auditorium.

P. T. Barnum had met a serious challenger in John Banvard. One week after Banvard’s opening, Barnum ran ads in the New York Times, crowing that his own museum was “THOROUGHLY VENTILATED! COOL! Delightful!! Cool!!! Elegant, Spacious, and Airy Halls.” This was hardly true, of course; Banvard’s building was far superior, and Barnum knew it. But Barnum had a grasp of advertising that not even Banvard could match. The rest of the summer was to see America’s greatest showmen–and its first entertainment millionaires–locked in an economic struggle to the death.

With each stab at innovation by Banvard, Barnum would parry with inferior copies but superior advertising. Banvard had the Mississippi panorama; Barnum had a Nile panorama, probably copied from Banvard’s. Banvard had the real “Cardiff Man” skeleton; Barnum had a fake. On and on the showmen battled throughout the summer, with the stage and the newspapers as their respective weapons of choice.

The struggle ended with shocking speed. Banvard was in far over his head; creditors were dunning him for payments, and shareholders were furious over the discovery that their stock had been worthless all along. On September 1–scarcely ten weeks after opening–Banvard’s Museum padlocked its doors.

Banvard improvised furiously. The building reopened one month later as Banvard’s Grand Opera House and Museum. Productions dropped in and out over the next six months–first a leering dance production, then adaptations of Our Mutual Friend and Uncle Tom’s Cabin. None was successful. Unable to make anything work, Banvard finally leased out the building to a group of promoters that included–perhaps to his chagrin—P. T. Barnum.

Banvard spent the next decade with the barest grasp on solvency, and then only by quietly appropriating lease money that should have been going to shareholders and other creditors. He and his wife lived virtually alone on their rambling sixty-acre estate; they were down to one servant for the whole property. After his shoddy treatment of the museum backers, no New Yorker would want to invest in a Banvard enterprise now; he wrote two more plays only to find that no producer would take them.

If his financial ethics were suspect, Banvard’s artistic integrity was suffering even more. The innovator had been reduced to plagiarism: first in his history book, The Court and Times of George IV, King of England (1875), which was lifted from a book written in 1831; and then again the next year, when he finally managed to write a play that opened in his old museum, now named the New Broadway Theatre. Corrina, A Tale of Sicily was not only plagiarized, it was plagiarized from a living and thoroughly annoyed playwright.

Humiliated and surrounded by creditors, Banvard desperately sought a buyer for his theater. P. T. Barnum, when approached, sent a crushing reply back to his old rival: “No sir!! I would not take the Broadway Theatre as a gift if I had to run it.” When Banvard finally did unload his decrepit building in 1879, he had to watch its new owners achieve exactly where he had failed. As Daly’s Theatre, the building thrived for decades before finally being torn down in 1920.

Banvard’s castle was not to be as long-lived as his museum. Banvard and his wife clung to Glenada for as long as they could, but by 1883, their deep entanglement in bankruptcy forced them to sell it. It eventually fell to the wrecking ball, and virtually all their other possessions were sold off to meet the demands of creditors. But the Mississippi panorama was spared from the auction block–now worn from nearly forty years of use, and nearly forgotten by the public, perhaps it was judged to be worthless anyway.

Banvard and his wife were now both well into their sixties and had scarcely any money to their name. They packed their few remaining belongings and quietly left New York. The only place left for them was what Banvard had left so long ago: the lonely, far-off American frontier. He was returning as he had left, a poor and forgotten painter.

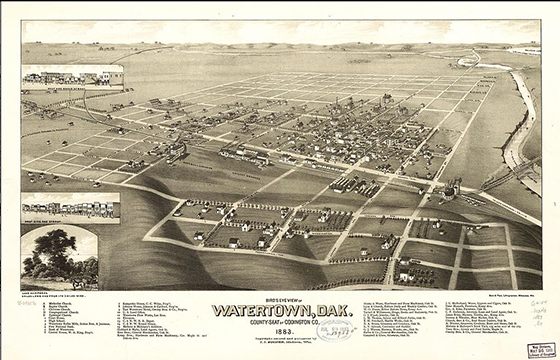

It was a deeply humbled and aged John Banvard that arrived in the frontier town of Watertown, in present-day South Dakota. He and his wife, the recent proprietors of a castle, had been reduced to living in a spare room of their son’s house. Eugene Banvard was an attorney with some interest in local public works and construction projects, and occasionally the elder Banvard renewed his energies of yore by pitching in with his son on these projects.

A bird’s eye illustration of Watertown, South Dakota, USA, from 1883 (Photo: J.J Stoner/Public Domain/WikiCommons)

For the most part, though, Banvard retreated into his writing. He was to write about seventeen hundred poems in his life—as many as Emily Dickinson—and like her, he only ever published a few of them. Unlike the more dubious plays and histories that he had “authored,” his poems appear to be original to Banvard, and sincere if not particularly innovative efforts. Taking up the pen name “Peter Pallette,” Banvard wrote hundreds of poems during his years in Watertown, becoming the state’s first published poet. One of Banvard’s more sustained efforts, published in Boston back in 1880 as The Origin of the Building of Solomon’s Temple, centered on the biblical brothers Ornan and Araunah. It opens with a standard Romantic invocation:

I’ll tell you a legend, a beautiful legend; A legend an Arab related to me. We sat by a fountain beneath a high

mountain, A mountain that soar’d by the Syrian sea: When a harvest moon shewed its silvery sheen, Which called into thought the Arabian’s theme.

The book’s epilogue descends into a miscellany of details about English church building, Egyptian obelisks, and loony speculations about Masonic oaths, a subject of apparently inexhaustible interest to the author.

On a more practical note, Banvard also authored a pocket-size treatise titled Banvard’s System of Short-Hand (1886)—one of the first books published in the Dakota Territories. He claimed the system could be learned within a week, and that he had been using it for years, keeping in practice by surreptitiously transcribing conversations on buses and ferryboats: “The author acquired the knowledge of shorthand precisely in this manner when he was but a youth .... He has many of these little volumes now in his possession and they have become quite of value as forming a daily journal of these times.”

For transcription practice, Banvard included his own poems and pithy maxims, such as “He jests at scars who never felt a wound.” Banvard had felt some wounds himself of late, and more were to come before his strange journey came to an end. But that same year, now into his seventies, he locked himself in his studio one last time, ready to produce a final masterpiece.

Dioramas and panoramas were no longer a novelty by 1886, and Edison’s miraculous work in motion pictures was just over the horizon. If the art form hadn’t aged well, neither had its greatest proponent–along with the usual infirmities of age and his ruined finances, Banvard’s eyesight had worsened with age. His eyes had never been terribly strong since his childhood laboratory mishap. Still, even now he could muster a certain heartiness. “In his mature years his appearance was like that of many Mississippi River pilots,” said one contemporary. “A thickset figure, with heavy features, bushy dark hair, and rounded beard.”

Nonetheless, Banvard’s family was uneasy with his notions of taking the show on the road one last time, as his daughter later recalled: “My mother and the older members of the family were quite averse to his giving it [the performance], as they felt his health was too impaired for him to attempt it.” If the older members of the family were against it, one can imagine the solace Banvard took in his grandchildren, who were only now seeing the family patriarch revive the art that had made him rich and famous long before they were even born.

For his diorama, Banvard had chosen a cataclysm still in the living memory of many Americans: “The Burning of Columbia.” Most of the capital city of South Carolina was burned to the ground by General Sherman’s troops in a day-long conflagration on February 17, 1865. Banvard’s rendition of it was by all accounts a magnificent performance. Even more impressively—in an echo of his humble beginnings–Banvard ran the diorama and a massed array of special effects as a one-man show. One audience member recalled:

Painted canvasses, ropes, windlasses, kerosene drums, lycopodium, screens, shutters, and revolving drums were his accessories. Marching battalions, dashing cavalry, roaring cannon, blazing buildings, the rattle of musketry, and the din of battle were the products, resulting in a final spectacle beyond belief, when one considers it was a one man show.

I have read of the millions expended in the production of a single modern movie, but when I remember what John Banvard did and accomplished in a spectacular illusion in Watertown, Dakota Territory, more than fifty years ago for an outlay of ten dollars, I am rather ashamed of Hollywood.

For all the spectacle, though, Banvard’s day had long passed. Dakota was simply too sparsely populated to support much of a traveling show, and the artist found himself packing away the scrims, drums, and screens for one last time, never to be used again.

A few years later, in 1889, his wife, Elizabeth, died. They had been married for more than forty years. As is so often the case in a long companionship, the spouse followed not long afterward. A visitor to Banvard’s Watertown grave will scarcely guess from the simple inscription that this was once the world’s richest artist:

JOHN BANVARD Born Nov. 15, 1815 Died May 16, 1891

As word of his death reached newspapers back East and in Europe, editors and columnists expressed amazement. How could this millionaire have died penniless on a lonely frontier? Had they sought to get any answers from his family, though, they would have come up empty-handed. Unable to pay their bills, the Banvards all fled town after the funeral.

In their haste to evacuate their house on 513 Northwest 2nd Street, they had left much behind, and an auction was held by creditors. Among John Banvard’s remaining possessions was a yellowed scrap of paper listing his unpd $15.51 bill for his own father’s funeral service in 1831. Young John had spent his life haunted by his father’s lonely death and humiliating bankruptcy. Sixty years later, still clutching the shameful funeral bill, he had met the same fate.

So where are his paintings?

His early panoramas of the Inferno, Venice, and Jerusalem were lost in a steamboat wreck in the 1840’s. A few small panels are scattered across South Dakota; the Robinson Museum, in Pierre, has three. Two more are in Watertown: the Kampeska Heritage Museum has “River Scene with Glenada,” while the Mellette Memorial Association has a hint of the “Three Mile Painting” with “Riverboats in Fog.”

And what of the paintings that made his fame and fortune, the ingenious moving panoramas? One grandson, interviewed many years later, remembered playing on the massive rolls when he was little. But after Banvard’s death, they lay abandoned to the auctioneer. Edith Banvard recalled in a 1948 interview: “I understood that part of it was used for scenery … in the Watertown opera house.” From there, she conjectured, the rolls may have been cut into pieces and sold as theater backdrops. Worn from decades of touring, and torn from their original context as moving pictures, they might have seemed little more than old rags. Not surprisingly, no record is known of what theaters might have done with them.

One persistent account, however, holds that Banvard’s masterpieces never left Watertown at all. They were shredded to insulate local houses—and there, imprisoned in the walls, they remain to this day.

Love this? Get the whole book here. From BANVARD’S FOLLY © 2001 by Paul Collins. Used by permission of St. Martin’s Press / Picador. All rights reserved.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook