The Mystery of a Medieval Blue Ink Has Been Solved

Turns out it was hiding in plain sight by the side of a Portuguese road.

During hot, dry summers in southern Portugal, the key ingredient for medieval manuscripts grows by the roadside. It is called folium, or turnsole, and it’s derived from the fruit of Chrozophora tinctoria, a small plant that grows in the region. For centuries, folium was responsible for coloring everything from Bible scenes to, later, the rind of a popular Dutch cheese.

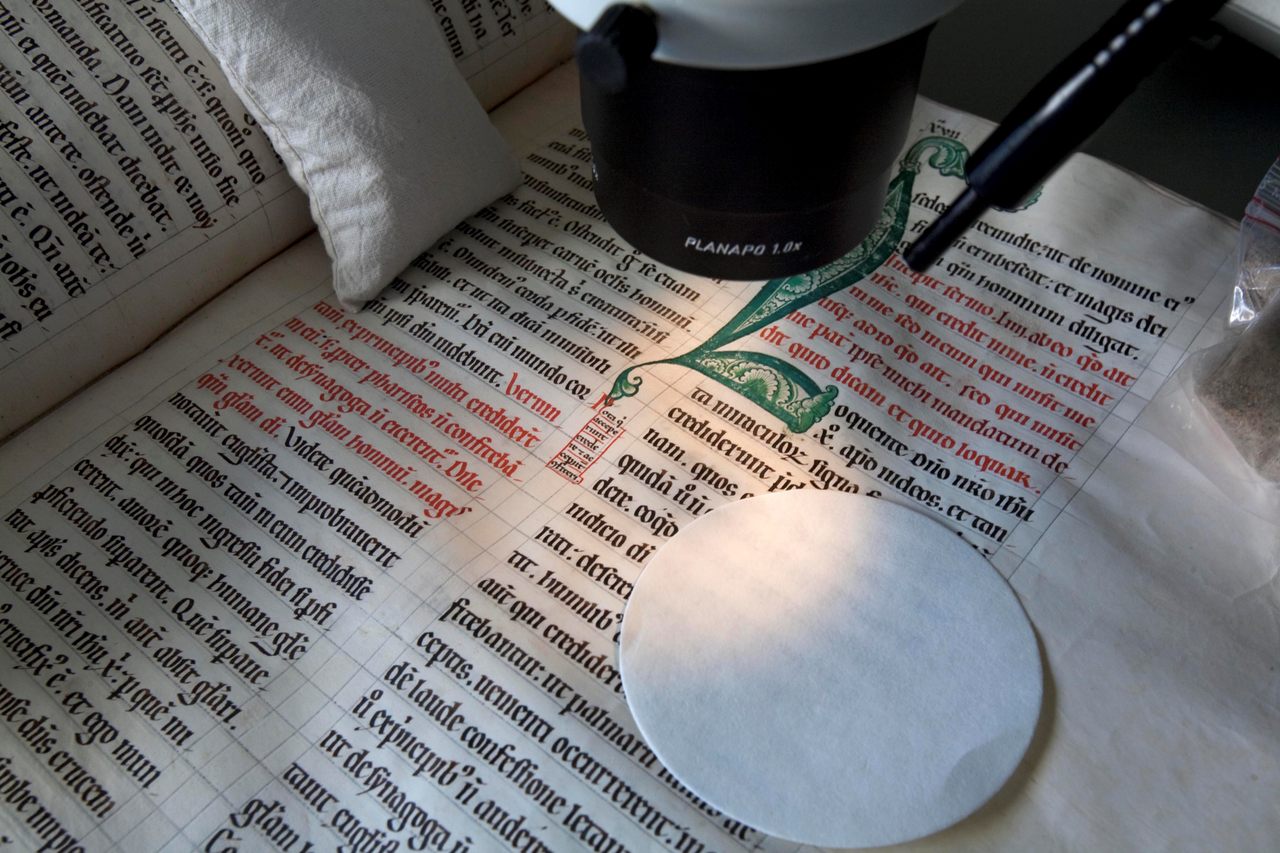

For the better part of the last century, however, the recipe for the vivid blue hue has been lost—until the publication of a new study in the journal Science Advances. While it was long known that Chrozophora tinctoria was the source of the ink’s sole ingredient, how folium was synthesized has eluded modern science. (The plant is not named in old sources, but detailed descriptions of it helped chemists connect the dots.) Relying primarily on a 15th-century guide for making the paints for illuminating manuscripts, a team of Portuguese researchers set about to resurrect folium.

“We’ve tried to mimic them, reading ancient texts,” says Maria João Melo, a conservation scientist at the New University of Lisbon and coauthor of the study. “Part of our expertise is to make this conversion from what is actually written and sometimes not so clear enough for us, and what they were making.”

Indigo was one of the main sources of blue ink for medieval manuscripts; folium was another. Whatever the source of the ink, it would be soaked onto small linen rectangles, and then shipped to workshops across Europe, to be used for a variety of purposes, from books to clothing.

As medieval manuscripts went out of style (thanks, Gutenberg), so, too, did original ways of extracting folium. Ironically, the ink that was a means of “illuminating” manuscripts went dark and slipped into obscurity.

The old practices had been documented, but were laborious and time-consuming. Melo’s team consulted an exhaustive list of instructions from the 15th century—literally, The book on how to make all the colour paints for illuminating books. But it isn’t exactly a modern cookbook. The manuscript was written in Judeao-Portugeuse, the extinct language used by the Jews of medieval Portugal. Besides translation matters, there’s more than one way to skin a cat, and other sources provided different instructions—and none of them provided a known name for the fruit behind the hue. Luckily, Melo’s source offered a lot of clues.

“It says how the plant looks, how the fruits look … it’s very specific, also telling you when where the plant grows, when you can collect it,” says Paula Nabais, a conservation scientist at the New University of Lisbon, and the study’s lead author. “We were able to understand what we needed to do to collect the fruits in the field ourselves, and then prepare the extracts.”

The team ventured into the southern, bleached-white town of Monsaraz to collect the fruit as per the manuscript’s instructions. The hairy plant’s fruit—about the size of a walnut—yielded a blue mixture. Careful not to crush the seeds, which the team realized jeopardized the quality of the ink, they identified the chemical compound that made the mixture, confirming folium’s identity on the molecular scale. It turns out folium is up with anthocyanins—the blue chemicals found in berries.

With luck, Melo says, the recipe behind folium can now be applied by conservators preserving old manuscripts. We’re finally catching up to medieval monks.

“They were able to produce paints that last centuries,” she says. “We don’t have such paints now. So this is part of our research—to know as much as possible about this material that was completely lost with the advent of the synthetic dyes.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook