What’s on the Menu in Your Fantasy World?

Meet three worldbuilders who bring their magical settings to life through food.

Food and fantasy have long gone hand in hand. Our oldest myths and fairy tales abound with ravenous monsters and enchanted apples, while modern fantasy literature has brought us the second breakfast-savoring hobbits of The Lord of the Rings and the sprawling medieval banquets of A Song of Ice and Fire. Fantasy fans rally around official cookbooks from the worlds they love, as well as unofficial recreations and fanfiction that explores the diets of their favorite characters.

So it’s no surprise that food is frequently used to enrich invented settings in the online worldbuilding community, where artists and writers come together to share their own fantasy creations. Some worldbuilders are developing the setting for a larger project, such as a comic, video game, or novel. Others build their setting around a specific interest, from constructed languages to speculative evolution. And worldbuilders don’t necessarily have a linear narrative in mind. For some, describing their world in an encyclopedic style is their chosen form of storytelling, using visual art, writing, and video to share their ideas.

Whether created as the backdrop to a story or just for their own sake, fantasy worlds are enlivened by details. Gastro Obscura spoke with three worldbuilders who believe that if you’re going to imagine a fictional society’s clothing, government, religion, language, and more, why not spend time thinking about what that society would eat?

Interviews have been condensed and edited for length and clarity.

Nakari Speardane, Elush and other projects

Londoner Nakari Speardane’s worldbuilding is informed by their study of archaeology and history. Speardane’s primary setting is Elush, which they describe as “a Neolithic sandbox” for playing with ideas about the emergence of customs and the patterns that shape human behavior. “I had started writing a book set in Elush, but realized I actually preferred the worldbuilding to the plot,” Speardane shares in a message on their Discord server, where they oversee a forum for worldbuilding discussion and critique. Speardane’s YouTube videos on worldbuilding feature original artwork and may take months of research.

Was food always something that you incorporated into your worldbuilding?

Not at all! I used to be a really fussy eater. Food made me feel anxious and isolated, and I didn’t understand it much.

At uni, a lecturer mentioned an article about how in regions where agriculture came before pottery, people tend to bake their staple grains. But in regions where pottery came first, they tend to boil or steam them. Western bread tends to be crusty, Asian bread tends to be soft, and that textural preference might go back to the start of agriculture. And that really fascinated me.

I use worldbuilding to play with the building blocks and patterns in our own world, and this seemed like a pretty significant one. Once I started seeing food as something that shapes identities, lifestyles, social structures, and relationships, it became really important in my worldbuilding.

Why is it important to make food a part of storytelling?

Paying attention to food makes a world feel more lived-in, like it has its own patterns of everyday life. Plus, food is great for storytelling because it’s so often a way to connect with others. It can characterize cultures, people, and the relationships between them. Everyone has food in common. Even if you can’t get the same ingredients in our world, knowing what their food tastes and feels like creates a physical link.

Think of the last thing you ate, and all the choices and labor that went into it. When you’re thinking of food as shaped by cultural trends and choices, you can apply the same questions to a different culture, or a different world.

What’s one detail of your own food worldbuilding that you are most proud of, or think is the coolest?

I think it’s really fun when small cultural differences about food snowball into big fundamental parts of viewing the world. In Elush, agriculture developed in a time of climatic instability, and people started getting really paranoid about having to share their food with their neighbors. So their houses developed interior courtyards to cook in, and special guest rooms, not considered part of the house, where people can visit their friends and eat together. The host is responsible for feeding their guests, creating relationships of obligation under the surface of a relaxed meal. They don’t like touching food, so they use utensils similar to chopsticks with a flat plate at the end.

But down south in the wetlands, agriculture never fully overshadowed fishing, hunting, and gathering. They never developed the paranoia, or the strict division between family and not, and they like sharing food with their friends. They eat with their hands, so their food tends to be drier than up north. Northerners often eat rice dumplings in a sticky sauce, while southerners eat steamed dumplings with sauce and fillings trapped inside.

The northerners think the southerners are invasively friendly and messy eaters, and the southerners think the northerners are fussy and rude, and that their houses are weird. And it all goes back to differences in food production.

Alex Greys, Looming Gaia

Alex Greys, based in Washington, U.S.A., has been writing and illustrating the world of Looming Gaia on Tumblr since 2017. She started focusing on the project as a creative outlet while dealing with chronic health conditions. “Looming Gaia has always been there to support me when my body won’t,” Greys shares in an email.

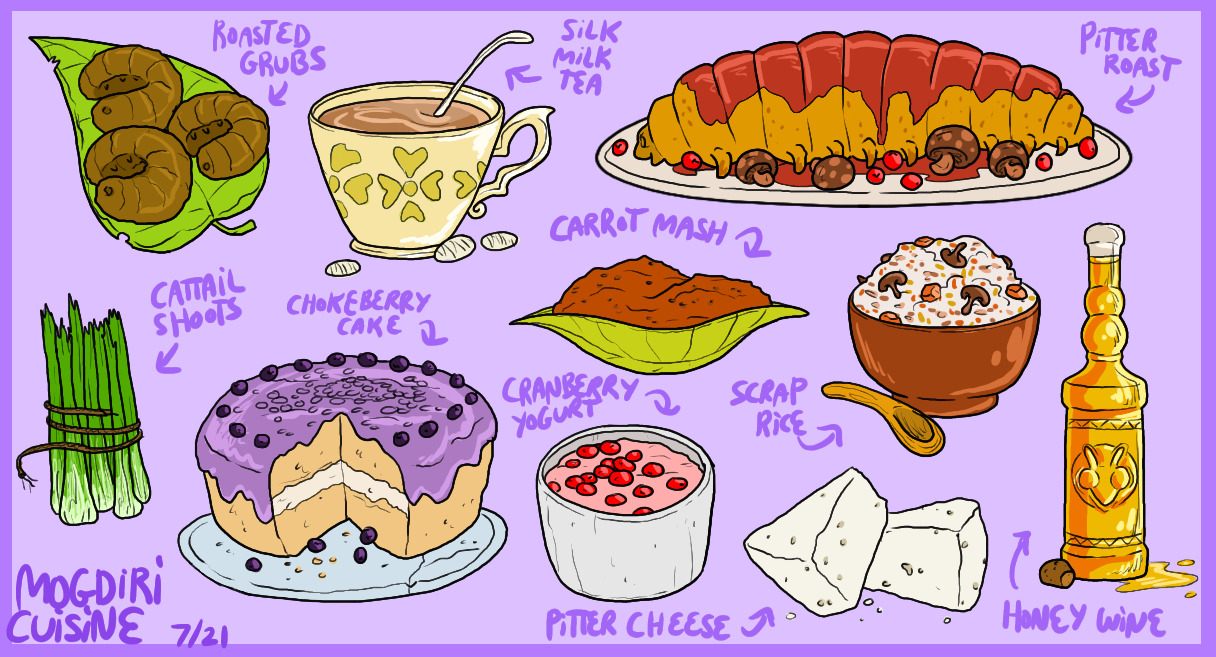

Inhabited by classic fantasy creatures like goblins alongside original creations, Looming Gaia features 11 national cuisines. “I try to create at least 10 traditional dishes per region, including a typical breakfast, lunch, dinner, dessert, snacks, and drinks both alcoholic and non-alcoholic,” Greys writes. “When all of them are put together, it can paint a vivid picture in the reader’s mind of what the whole culture is like.” As an example, she cites the nation of Mogdir: “a kingdom of magic-users who refuse to eat animals for cultural reasons, but they don’t consider insects to be animals. I had to come up with traditional cuisine that centered around bugs and bug byproducts.”

How did food become a part of your worldbuilding?

Even though cuisine is so essential in real-world cultures, it wasn’t something I thought about until several years into my project. I believe this is because my health conditions really limited my diet. I could only tolerate the same three or four bland foods every day for years on end, and this was driving me insane.

Cooking for other people fixed my damaged relationship with food. I was still stuck on the same bland diet due to my health, but I didn’t resent food anymore. I finally saw the value in cuisine as an artform and developed an interest in it, so I decided to incorporate it into my worldbuilding.

Why is it important to consider the food that characters in a fantasy world are eating?

Cuisine can say so much. It opens the doors to all kinds of stories and concepts. When you examine what’s on a character’s plate, you get a glimpse of what crops and meats are available to them, and this forces the worldbuilder to consider things like the climate and geography of that location. It all ties together.

It also gives the worldbuilder an opportunity to explore cultural practices. Maybe they are from a purely vegetarian or carnivorous culture, and the worldbuilder must come up with reasons why that might be.

Let’s say you wanted to create a culture that lives in an Arctic tundra environment. You decide that their native cuisine is hippopotamus meat and coconuts, because it sounds cool; but you should ask yourself if that really makes sense, when their environment doesn’t support those plants and animals. As you write the answers, you’ll find pieces of a puzzle naturally coming together.

Where do you get inspiration from?

Inspiration comes from everywhere! Sometimes I look at real-world cuisines from regions that are similar to my own, and I ask myself if these dishes would make sense in my lore. If not, I can tweak them as needed and create something more original.

I take a lot of inspiration from what animals eat too. When you’re writing fantasy creatures with animal traits like centaurs and satyrs, I think it’s helpful to look at what their animal counterparts eat in the real world. Do they have specific nutritional needs? Do they have to eat hard things to grind down their teeth? Do they eat little stones to help them digest stuff? These dietary factors can carry over into fantasy species and make them more interesting.

Amaiguri, Yssaia

Isabelle Farmer, known online as Amaiguri, is a professional game developer based in Colorado. Her world of Yssaia draws from real cultures like the Sakha people of the Arctic, among other sources, and she uses various media to depict its food. Amaiguri’s YouTube video about the cuisines of Yssaia mixes original artwork with live video in which her characters are represented by puppets. Yssaian food, she notes, ranges ”from the spider-crab chowders with black parsley of the North to wheat-based fry-breads in the South.”

Amaiguri is now developing an Yssaia video game in which food will remain an essential component. “That gives me the opportunity to showcase my worldbuilding in a way that’s a little bit less dense,” she says. She explains that in a game, “you don’t have to read a paragraph about the food; you just walk into someone’s house and see them cooking … and that’s a set-dressing for the narrative that is happening.”

Amaiguri describes a scenario in which eating could also progress the game’s narrative: the player must learn to use chopsticks along with their character. “That can be a metaphor for someone growing more accustomed to a culture,” she says. “During the eating scenes, it’ll get easier because you’ll be more used to it, just like the character.”

When did you start thinking about food as an aspect of worldbuilding?

When I started getting more serious about my worldbuilding, I saw that a lot of people were talking about how worldbuilding has to come from geopolitics. And those geopolitics are emphasized in what people eat.

I still mostly do worldbuilding to support a story. But as my stories have gotten more political—as I have become more politically aware in the real world—I have realized that you can’t write a political fantasy if you don’t talk about the food. Because the reason countries or factions make decisions is about resources, and food is one of those key resources.

What’s the most important thing for you to consider when worldbuilding food?

If I say, “[In the north of Yssaia,] they eat bread and beef” to an American audience, that would be extremely boring. But if I say, “Their grain is all black because it’s partly [grown] underground, so it’s trying to absorb as much light as possible,” it sounds appealing to a normal audience because it sounds fantastical and weird, and also to a worldbuilding crowd that is super interested in the details of “why is the food black?”

The North has this Gothic vibe in general. The buildings are black and gloomy and have that dark, edgy-looking aesthetic. So it’s really cool to be able to find an ecological excuse to make the rest of the environment also super Goth.

Tell me about the YouTube video you made with another worldbuilder where you cooked recipes from your worlds together.

That was me and SpaceDirt! We each made a dish from our respective fantasy worlds. His channel is about linguistics more than food, but he is also really knowledgeable about cooking. We had planned to have llama meat shipped in—or alpaca, I forget which one we went for. I found a farm that had it, and they said they were going to ship it to us overnight. But they didn’t send it to us!

The whole point of the collab was for us both to pitch in for something super unique, but we had to scramble. I think I just got bison meat at the end of the day, which was still a little unique. And the food was still good!

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook