For Fraggers, Coral Collecting is Serious Business

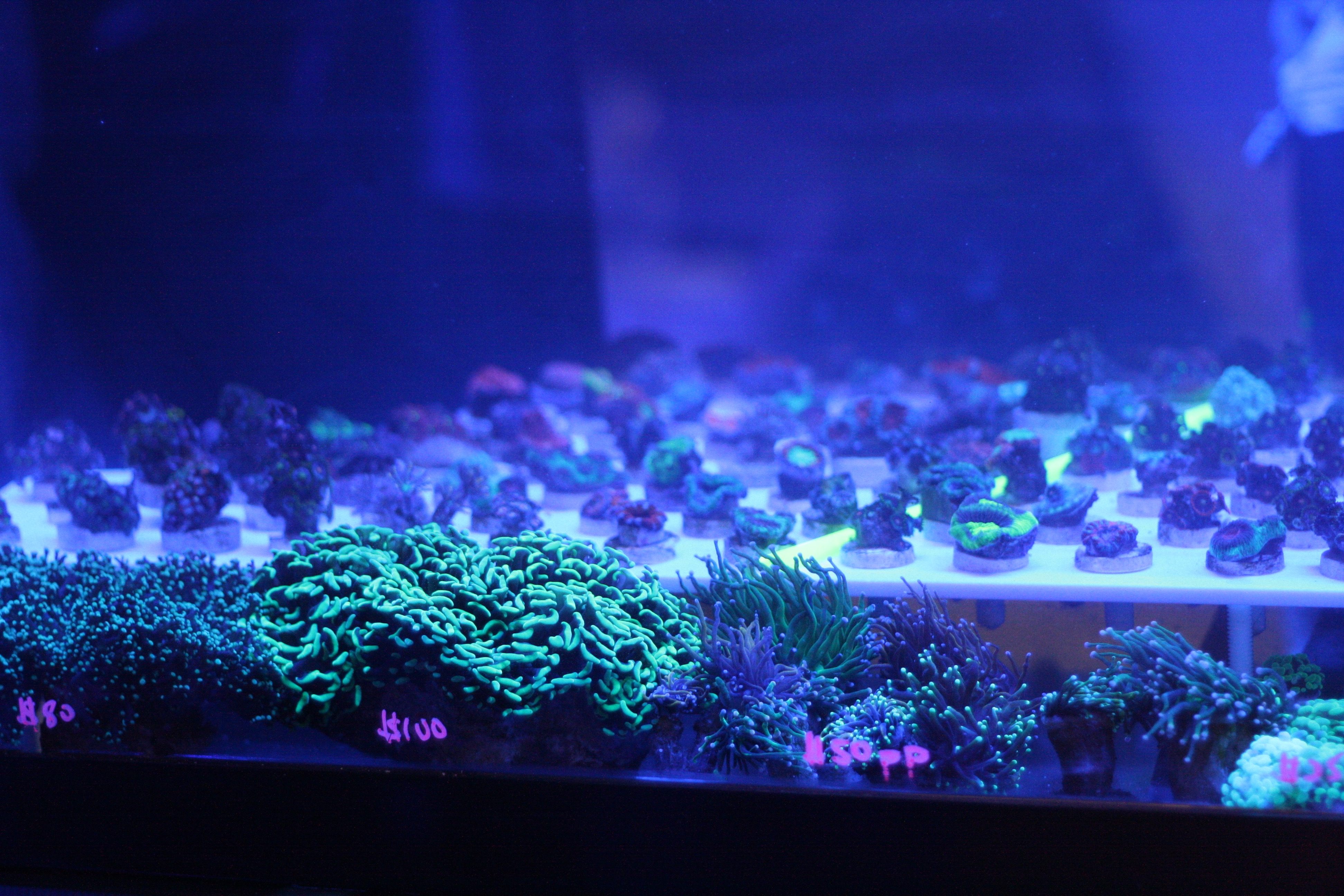

Burbling tanks of frags for sale glow under blacklights at the Manhattan Reefs Fall Frag Swap. (Photo: Kyle Frischkorn)

Early on a Sunday morning in November, a bunch of fraggers from an online forum gathered in a blacklight-infused room in lower Manhattan to exchange merchandise.

The 200 or so attendees were there in search of something most people don’t spend a lot of time thinking about: coral. Fraggers are people who buy, sell, and swap coral fragments, or “frags,” for their own home aquariums. At this New York event, around 200 fraggers gathered in the student union of Pace University for a “frag swap,” in which professionals and hobbyists alike set up table displays of their best pieces of coral.

Frag swaps are as much for the community as they are for buying and selling. People milled around the big room as vendors set up aquariums holding coral to buy and sell. Every once in a while you would hear the loud whirr of a spinning blade cutting off a coral fragment. Many participants had coolers in their hands, each filled with plastic bags containing corals they were planning on swapping.

Coolers to keep corals at appropriate temperatures during transit are critical gear for fraggers. (Photo: Kyle Frischkorn)

The tying bind was a love of colorful saltwater-filled basins and every sort of organism they support. These people keep aquariums in their homes and pride themselves on the diversity of wildlife contained in them. They frequently converse online via ’90s-esque HTML forums, most of which contain the word “reef” or ‘frag” in the title. One of the more popular sites, Manhattan Reefs., hosted the New York frag swap.

The hobby of home saltwater reef upkeep—or as some more entrenched participants call it, “reef aquarium husbandry”—has been around for decades. At the event was a man named Paul Baldassano, who proudly proclaimed that he owns the oldest saltwater aquarium in the country. It’s been going strong since 1971. Since then, he has built and maintained (or, rather, husbanded) many more aquariums and even invented a few tools to make coral maintenance easier.

Frags are prepared to order by using a bone saw to cleave branches from the mother coral. (Photo: Kyle Frischkorn)

Baldassano considers himself a master saltwater aquarium keeper, although it’s always been just a hobby for the born-and-raised New Yorker. Through trial and error he taught himself how to keep organisms alive in the small tanks, and has even written a book about his travails as a hobbyist saltwater aquarium owner. Now, he says, things are different than 40 years ago. The methods he helped create have come and gone, and now other supposed experts discuss the topic online. But more often than not, these other hobbyists are wrong. “Not that the internet is a bad thing,” he writes in his book The Avant-Garde Marine Biologist, “but there are just too many opinions and no fact checkers online.”

Sure enough there were numerous other amateur fraggers eager to share their knowledge at this frag swap. One man, who went by the name of Tony and wore orange goggles to better see the corals’ color, explained that his interest in coral was thanks to his marine biologist wife. After one of her trips to sea she brought home a few specimens, which led the couple to buy their own aquariums.

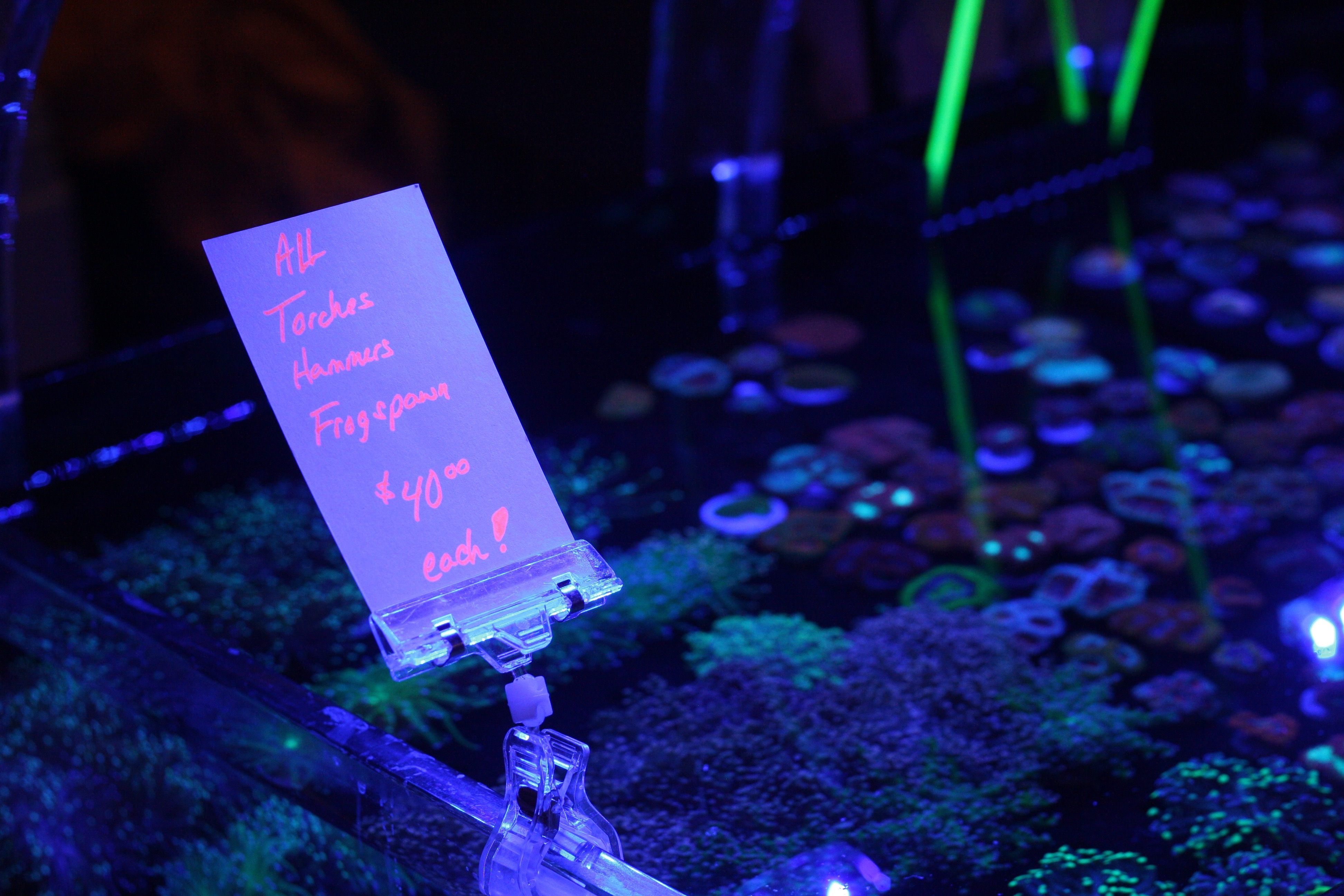

Fraggers use blacklights to draw attention to healthy corals—and hot deals. (Photo: Kyle Frischkorn)

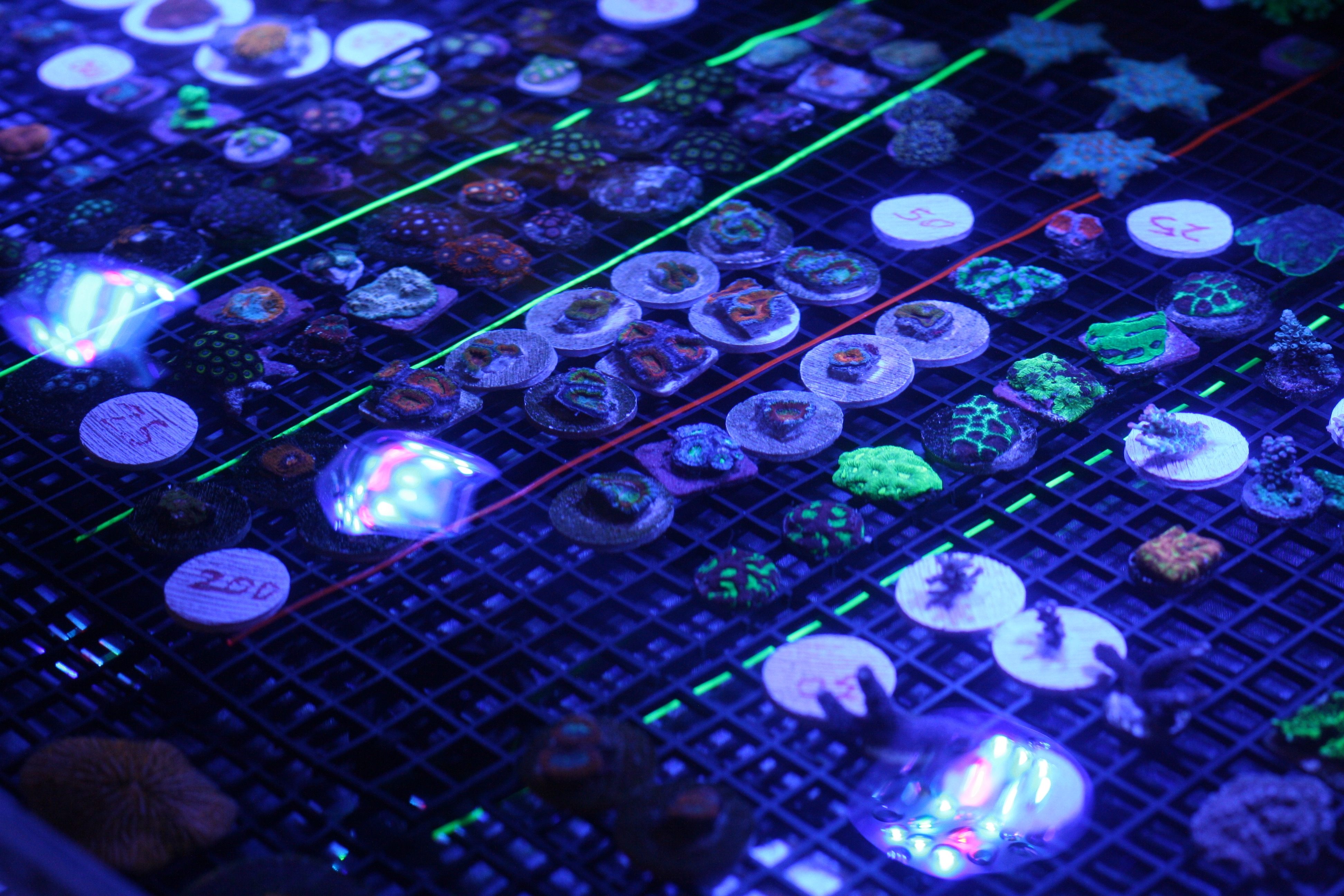

What started as a benign hobby turned into a valued and expensive collection. “I basically spend a paycheck a month,” Tony said while perusing potential coral to buy. Over the years his aquariums grew and so did his eye for specific types he wanted to raise. He often meets with other fraggers to buy or swap coral—he had in fact brought his cooler to do just that. But he also studied which organisms he was going to purchase from a vendor. On this day he had his eye on a $300 piece of coral. He said it was about an inch wide but looked like “a rainbow chalice.”

People like Tony are not outliers. The market for coral is huge. Estimates put the official coral trade at over a billion dollars every year, but this doesn’t necessarily apply to fraggers. Trade refers to official commerce from source countries to coral vendors. But given the demand for these coral, you can only extrapolate that the underground market between hobbyist fraggers is also quite large.

“It’s a fairly big market,” explained marine biology Professor Andrew Rhyne of Roger Williams University, who studies trends in marine ornamental aquaria. At the same time, he added “we don’t have very good numbers.” He and a group of other scholars have put together a project with the New England Aquarium to collect and analyze data related to marine aquarium biodiversity and its international trade.

Coral fragments roughly the size of a silver dollar can fetch up to $200 at frag swaps. (Photo: Kyle Frischkorn)

More marine biologists are focusing on this topic of late as coral reefs are on a steep decline. Ocean temperatures have been rising, and other environmental factors like this year’s strong, Pacific Ocean-warming El Niño have been messing with the aquatic environment. These have led to what’s known as “coral bleaching,” which happens when coral reefs expel algae and lose their color. This stress-induced event eventually leads to coral starvation. One estimate has as many as 4,000 square miles of coral dying by year’s end. Other factors like ocean acidification have also led to a steady decline in coral population. Couple that with the growing trade, and there’s undoubtedly a coral disaster nearing.

Are fraggers aiding in this coral endangerment? The answer is complicated. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration last year upped the number of endangered coral species to over 20. This, reported National Geographic, is 10 times the number of coral species ever put on the list before. This means that many coral species are facing extinction if they aren’t properly protected. Some conservationists say that trade and fragging may help further this depletion of the organisms.

Interestingly enough, some fraggers claim just the opposite. At the swap event, a few hobbyists who were more than aware of the coral crisis said they didn’t necessarily see themselves as the problem. To them, fragging may actually help create coral biodiversity, as they are growing specimens in conditions that won’t ultimately kill them. Moreover, the increased interest in coral is putting a newfound spotlight on the species.

Coral enthusiasts peruse the the displays of frags for sale. (Photo: Kyle Frischkorn)

Professor Rhyne admits that fragging likely doesn’t have a huge impact on the global decline, but that doesn’t mean that coral swappers are coral saviors. Fraggers ”have very little impact on coral conservation, unless they act,” he said. In short, what good is conserving a species of coral if you’re not going to actually reintroduce it or use it to help out with the greater conservation effort? Most fraggers are swapping their goods to make their aquarium look more colorful.

Whether the official coral trade impacts future species is also complex. The NOAA, in its multi-hundred-page report about the status of coral conservation, admitted that trade does impact coral populations. But compared to other problems such as climate change, pollution, and over-fishing, the effects are “minor.”

Even so, this likely will not stop fraggers from continuing their passion for coral. People like Baldassano and Tony will continue to find local swaps, and online forums in dozens of countries will continue to be populated with questions, tips, and frag offers. For them it’s not only the goods being hawked but the people behind it.

As Tony put it, “it’s become more of a community thing.” That is, thousands of small communities exchanging heaps of money for colorful salty objects.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook