A Forest of Furniture Is Growing in England

A decade-long plan is finally approaching fruition.

The rain was streaming down on the summer afternoon in 2012 when Gavin Munro realized with chagrin that he had gotten exactly what he’d wished for.

He had spent the morning hunched over in his black slicker, working willow branches into new shapes. Lunch had been miso soup and oatcakes, same as every day, and after that frugal meal it had been hard to convince himself to return to the field. It was 3:00, when he paused each afternoon to take a picture, as a marker of time in a decade-long plan. Even now, standing in a forest of chairs sprouting directly from the ground, it was hard to believe that plan could work.

He paused a long moment, alone, before stooping back down, thinking—“Shit, I got what I asked for. I’m a chair farmer.”

Six years earlier, in 2006, Munro had started work on his grand vision. It was a big, mad idea that he had become so obsessed with that one friend had picked a safe word—“haberdashery”—that would make him stop talking about it. Munro wanted to change the way people think about manufacturing. It might take a day to assemble enough flat-pack furniture to fill a house, but the timber cut down to make it all needs decades to grow. Even the cheapest wooden chairs require a wealth of time to create. Munro’s big idea was that he would guide trees to grow into chairs, tables, and lamps that could be harvested right out of a field. The trees, selected for their ability to grow new sprouts from their stumps, would regenerate. His forest would yield furniture the way an orchard yields apples.

He started a company, Full Grown, to pursue his plan, and that day in 2012 when he stopped and took stock of where it had led him, he was more than halfway through the decade that he had given himself to grow his first crop. He had yet to harvest a single chair.

The narrow road to Munro’s chair forest runs between close stone walls, along a route worn deep by years of cattle walking into Wirksworth, England. Ed Lound, who said he’d be easy to recognize because no one else in town has blond dreadlocks, knows exactly which bits of road can accommodate both his jeep and a car heading in the other direction. His family moved here when he was five years old, which makes him a newcomer in what he calls a “really old place.” Some local historians believe Wirksworth is the site of the lost Roman city of Lutudarum, which had been built to mine lead from somewhere here in Derbyshire. In the parish church, there’s a piece of old stonework, originally found in a 13th-century building, that shows a man holding a pick and a basket. It’s said to be the oldest representation of a miner anywhere in the world: T’owd Man.

People who’ve spent most of their lives in this town—even those who were born here but whose families came from elsewhere—still aren’t considered true Wirksworthians. Munro, born one town over, in Matlock, is as much a foreigner as the wealthy interlopers from the south buying up local real estate. If the roots that anchor Munro and Lound to this place are shallower than others’, they’re still part of a deep, strong network. Munro, whose wife grew up in Wirksworth, met Lound through friends and hired him in 2014, fresh out of the University of York with a degree in criminology. More than three years later, Lound knows the 2,000 or so trees in the forest as well as Munro does.

Just inside a gate, there are rows of ash, oak, sycamore, and hazel, alongside red-headed beech and self-seeding goat willow. Each individual tree is being formed into a piece of furniture. Saying that you’re going to visit a forest of chairs in the English Midlands sounds like you’re embarking on an adventure in Narnia, and in Munro’s original vision, he imagined chairs and tables lined up in neat orchard rows. The field is wilder than that. Berries grow among the trees, pheasants and rabbits nestle in the grass, harvest mice live in the shed, and birds nest in the lamps. But it doesn’t feel so different from other agricultural places until you walk down rows and see trees with, simultaneously, all their usual attributes—branches, leaves, roots—and all the attributes of chairs—backs, seats, legs, set at right angles.

The chairs grow upside-down, their four legs stretching up toward the sky. Lound grabs hold of one that’s almost ready for harvest. “It’s thickening up at the right level,” he says, as if describing a prized farm animal. “It’s just level and sturdy. If you do that”—he shakes the branch—“the whole tree moves.”

We’re looking at one of the most promising chairs in the field, which represents years of trial and error. According to Munro’s original plan, the first crop of chairs should have been harvested by 2016, but most of the pieces, more than 500 in all, are still in the field, including a row of squat, spiral lamps planned as a quick cash crop. “Making trees do what they don’t want to do is really bad, and see how shallow we’ve laid these branches?” says Lound, pointing at one of the lamps. “That’s not what a tree wants to do.”

A tree has a basic plan, embedded in its cells, for optimizing its position in the world. When Munro first started to experiment with training trees, he tried to join sets of four, with one tree for each leg, into chairs that were supposed to grow from the ground up. The trees resisted. Planted close together, they competed for light and space, and one would always come to dominate at the expense of its neighbors. Munro was bossy with them, too, and would nudge them in directions they wouldn’t usually go. They grew cautious. Their progress slowed, or they gave up on branches he had bent into his designs, which left some chair-parts too skinny and underdeveloped, while others continued to fatten.

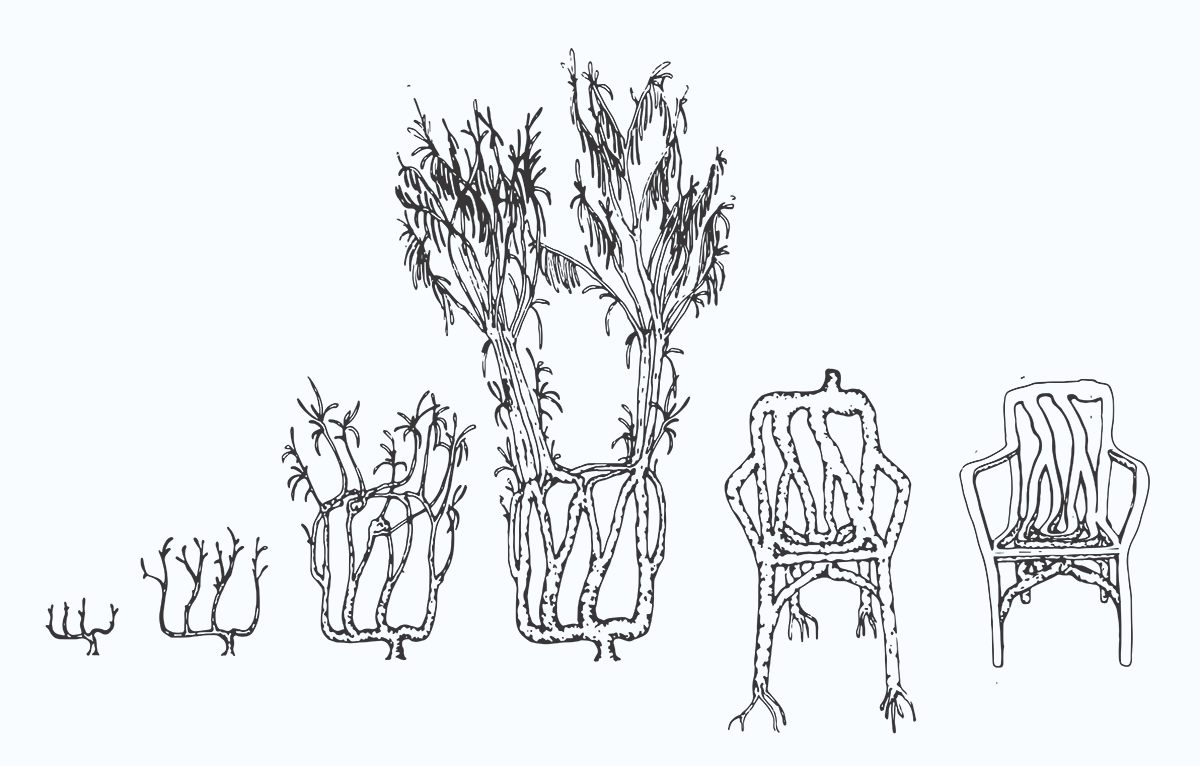

For every branch that becomes part of the chair, the tree wants to grow many more. Guiding a tree’s growth begins with selecting branches that seem most naturally inclined to reach in a given direction. At the beginning, the tree doesn’t look much like a tree at all, but a wide T-shape stuck into the earth. As more branches bud and grow, the most amenable ones are tied to frames that keep them in line. Later they’re bent to form the angles of the chair’s seat or legs. Pruning slows the growth of parts of the chair while other parts continue to develop, and grafts join branches together to make the chairs’ legs.

Full Grown’s earlier chair designs required accommodations from the tree: One branch, for instance, was supposed to split into two, with one limb continuing skyward as part of a back leg while the other became part of the chair’s seat and then was curved to form a front leg. But the tree favored the back leg, so the design had to change, with separate branches forming each leg. “We were trying to design it like a chair,” says Lound. “Whereas now we’re trying to grow a tree.”

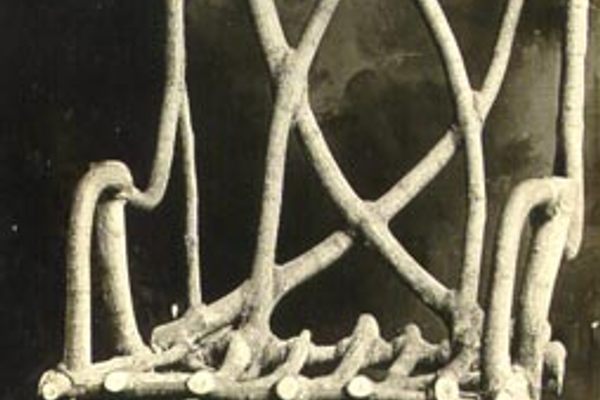

All along, Munro knew it should be possible to coax a tree into becoming a chair. In the Full Grown office he keeps a picture of the throne-like “Chair That Grew,” started from seed and harvested in 1914 by John Krubsack, a Wisconsin banker and gentleman farmer. In the century since, others have independently rediscovered the idea of tree-shaping, always working alone, rarely sharing their knowledge with anyone else.

Among the few people in the world who have dedicated themselves to this craft, bending trees to their own designs, Axel Erlandson, a farmer in California, was the first to turn it into an art form. “He was really the master,” says Lound. “He got it down, and then he died without telling anyone how he did it, which really didn’t help at all.”

Erlandson was dedicated to precision, able to convince his trees to grow exactly as he imagined they could. He had worked as a surveyor, and he drafted plans for his trees as if he was creating a map, accurate to 1/1000 of a foot. In 1929, four years after he began this work, he sketched out a design for his Poplar Archway, which required 10 trees, planted 18 inches apart, to grow into a lattice of Gothic-like windows, with a three-foot doorway set in the center. His wife was skeptical. She wrote, on the same page as his drawing, “I do not believe that Axel can get a tree to grow like this illustration.” On the other half of the page, he wrote, “I believe I can get a tree to grow like this illustration.” He was correct.

Erlandson’s formal schooling had stopped after fourth grade, but he had always been adept at understanding complicated machines. He had built a working wooden model of a threshing machine as a young man in Minnesota and, later, windmills to suck up water and irrigate his arid California farmland. He owned a motorcycle, in days when motorcycles needed even more constant attention than they do today, and drove it across the country. To him, the workings of trees posed a new puzzle.

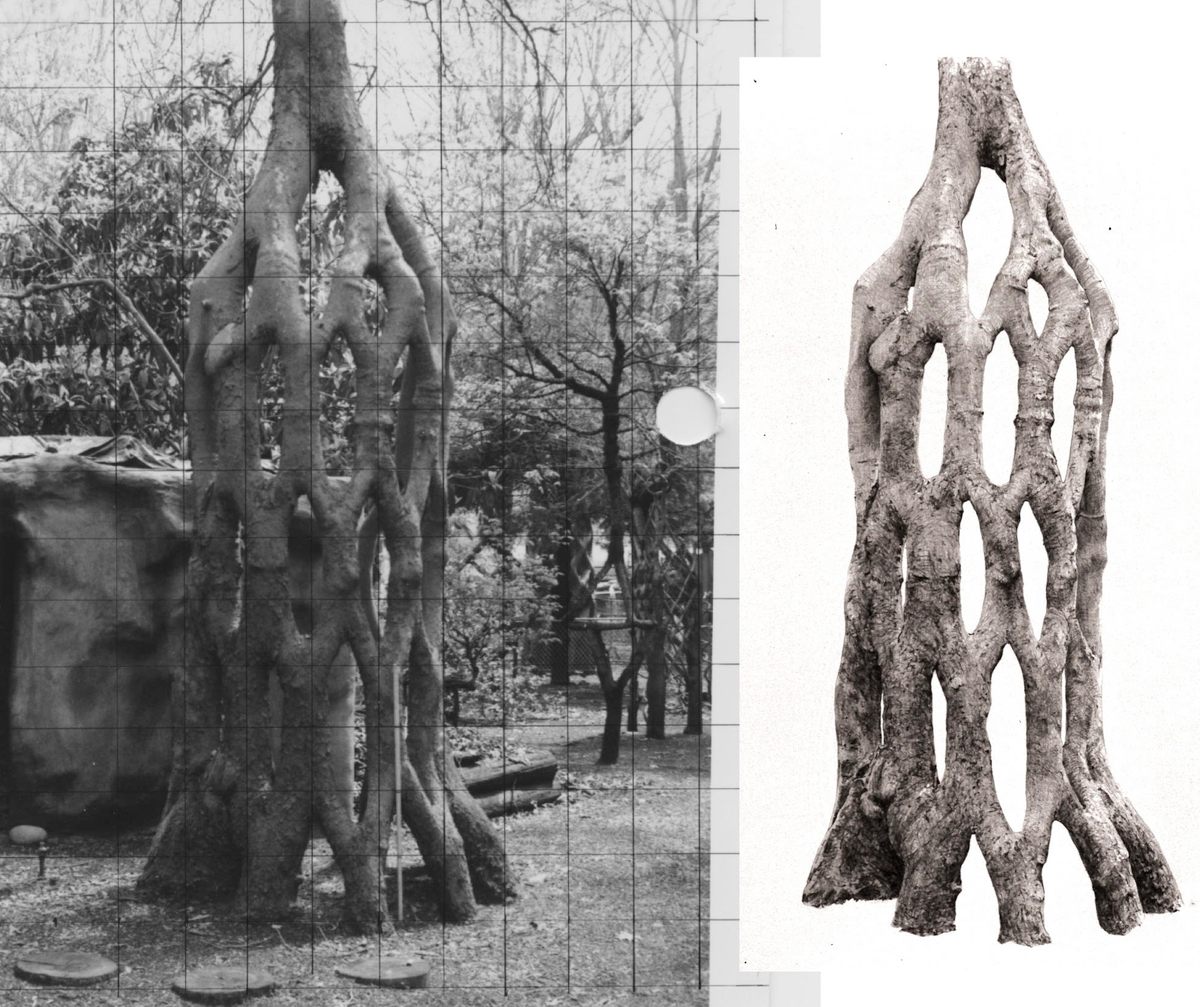

The idea of training trees into unique shapes came to him on his farm in the Central Valley. He had planted a row of trees as a windbreak for his crops, and he noticed that some branches lost their bark and began to graft together as the wind rubbed them against one another. Experimenting with the shape of trees became a hobby. One of the first trees he designed, the Four-Legged Giant, was a sycamore made of four individual trees grafted together to become one, which straddled the ground like an invader from Mars.

He created wonderful, fantastical shapes, which no one had dreamed trees could form. There was the Two-Legged Tree, which stood astride a pathway with a pair of perfectly arched legs, and trees with trunks that branched into circles, cubes, and spheres, before rejoining and growing straight up toward the sky. There was a tree grown into a double-helix, a tree ladder, a base turned into a cage that a person could step inside. Another creation, the Basket Tree, had a towering tube of diamond latticework in place of a trunk.

How he shaped these trees with such precision is a mystery. He believed that he had only begun to discover the possibilities of this art, and that “a person could grow a grove of trees of designs so much more intricate than I have here that they would make my present place look quite simple in comparison,” he wrote in a letter in 1953. But he never taught anyone his craft before he died, nine years later.

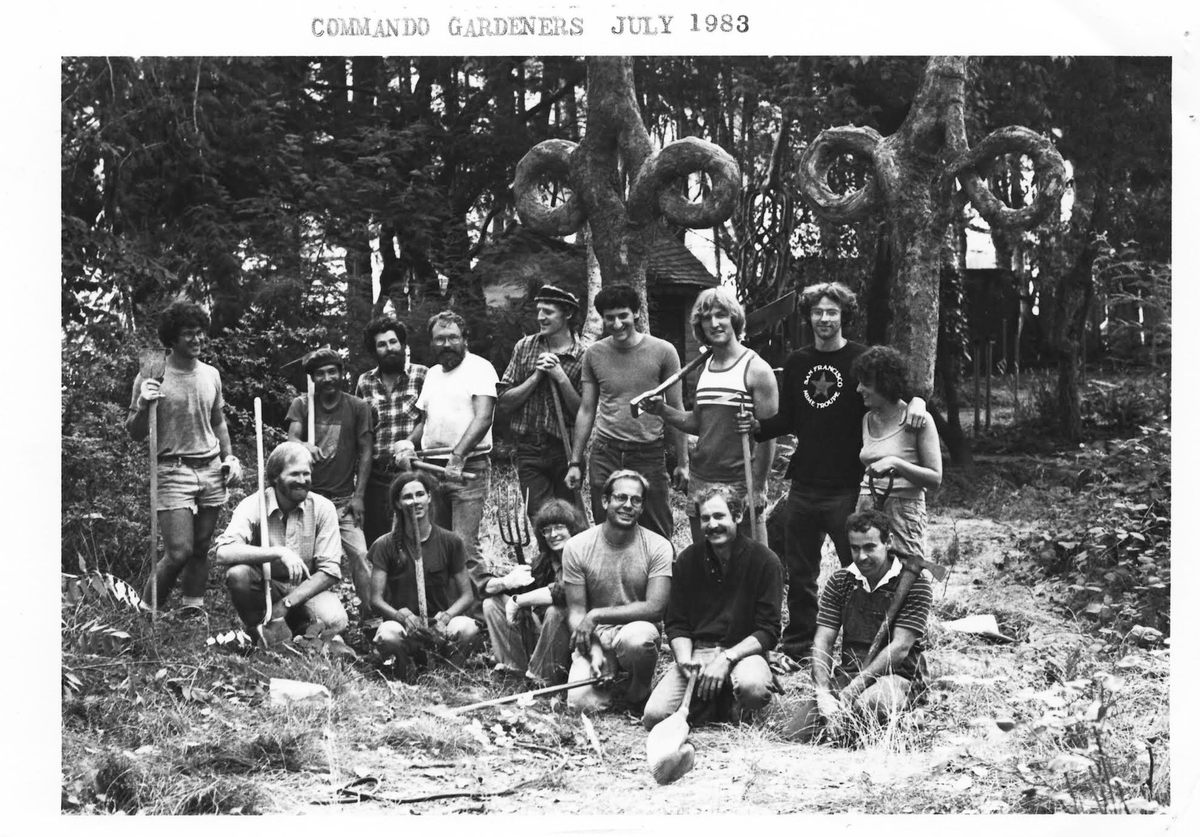

“I think he enjoyed that people were just amazed,” says Mark Primack, a Santa Cruz architect whose fascination with living structures led him to Erlandson’s trees. Primack is responsible for collecting many of the details of Erlandson’s life that are known today, and helped save the inhabitants of the Tree Circus when the property was in danger of development. “He may have done grafts and stuck nails through the branches to hold them together, but that’s all covered up now and internalized,” Primack says. “As one of his trees ages, it grows over all his ministrations. It just becomes a tree, a form. There are no signs of how he did it.”

Erlandson considered his work, in the idiom of World War II, a “non-essential industry.” In 1946, his wife and daughter convinced him to start a “Tree Circus” in Santa Cruz, where they charged visitors 25 cents to walk between the legs of the Four-Legged Giant and into a park filled with the “world’s strangest trees.” But it failed to thrive. Business was never strong, and when a new highway bypassed the Circus’ road, even fewer customers found their way there.

“The principle things we need this world are surely food, clothing, and shelter, and growing these kind of trees can hardly help to satisfy any of those needs,” Erlandson wrote in that 1953 letter.

But there are people now who believe that techniques like his can be used to serve more practical ends. A group of German architects, engineers, and scientists are developing principles of experimental “Baubotanik” architecture, in which trees are grown into shelters. One of the test projects is a three-story tower in a lattice pattern reminiscent of Erlandson’s work. And at Full Grown, Munro and his colleagues believe that they can create a woodland that regularly produces furniture—a “factory where birds will like living,” as Munro puts it. Far into the future, people still are going to want places to sit and surfaces to eat from, and if the company does create a new mode of mass production, a forest that grows chairs, it could provide durable, beautiful objects to serve basic human needs.

The strength of Full Grown’s furniture comes, in part, from the grafts that knit the branches together. When the top layer of bark is rubbed away, leaving a layer of growth cells exposed, that wood will join with the tissue of another branch, so that the two limbs grow together as if they were one. A friend of Munro’s once pointed out that he must know what that feels like, in a way. Munro was born with vertebrae in his neck fused and malformed, a rare bone disease called Klippel-Feil syndrome, and when he was young, doctors broke those bones and reset them. He had to wear a metal frame that kept his spine in place while the bone grafts healed. Even today, long hours in the field can leave him in pain.

When Munro first started growing trees in the field, he used to huddle for warmth where the cows from the next field over would congregate. Eventually he pulled a small RV onto the site, and later upgraded to a more permanent shed. For the past two winters, though, the company has had an office in town, in a low building that was once part of an engine-block facility. Now the warmth comes from a space heater and tea instead of a herd of cows.

On the office wall, Munro has laid out a new timeline—this one made of bright sticky notes—that imagines his company’s growth years into the future. “We’re trying to make the transition from art students and a criminology student into actually running a business,” says Munro. They’ve been taking preorders for chairs, tables, and lamps, but they eventually want to be able to sell off-the-shelf, finished pieces. The timeline goes out to 2031 and includes Lound’s 30th birthday, as well as the 50th for Munro and Chris Robinson, who went to art school with Munro and is now helping in the field and with new designs. “By the time Ed’s 30 we’re going to be sitting around a giant dining table that we grew. By the time Chris is 50, we’re going to be planting a new farm on land we own,” Munro says. “By the time I’m 50, everything will be smooth sailing.”

In the chilly back room, a small collection of furniture that has been harvested from the field is drying out. Curlicue lamps hang from the ceiling, and leggy table prototypes crowd together in a corner. Some pieces are still raw, covered in bark, but a few have had some of their surfaces sanded down to smooth, blond wood. In this room is also a single chair, harvested this past fall. Since 2012, other prototypes have come out of the field, but this is the first Full Grown chair that it’s possible to sit on with confidence. Munro has been using it, on occasion, as an office chair.

The chair, shorn of its leafy branches and turned right-side up, looks unashamedly chair-like, apart from the nubbin on the curve of its back, where it was once connected to a trunk. It’s still covered in bark, though, and retains an essential tree-ness. The legs are sturdy, and where most chairs have a flat slab to sit on, this one has set of curved branches. However, one side of the seat’s front edge is too fragile: The tree had directed its resources elsewhere. “But you can lean back, and it’s quite comfy,” Munro says, demonstrating the gentlest way to sit down. It’s taken more than a decade to reach this simple moment.

The chair is strong and supportive. The branches that make the back have a slight give, and the edges wrap ever so slightly around the shoulders of a slim person. Leaning back feels like a gentle embrace, like a trust fall with a tree.

Before harvesting any more chairs, Munro wants to make sure their branches grow even thicker than these, so they leave smaller gaps in the seat and back. After they’re harvested and dried, their outer edges will be planed and sanded silky smooth. Any surface that might touch a person’s body will get this treatment, but the undersides of the arms and seat, along with other interior surfaces, will keep their bark. The exposed wood’s then rubbed down with oil for polish and smoothness.

It won’t look exactly like any other chair, but ideally it won’t be immediately obvious how the chair was made, either. “Just so that it’s not as in your face,” says Robinson. “So it’s not the first thing you think of. The first thing you think is, ‘Oh, that’s a really nice chair.’”

Munro goes to the bookshelf and comes back with a tome of Euclidean geometry, full of bright lines in primary colors, that describes basic shapes and their rules. One of his close-held desires is to grow a piece in the shape of a cube, and he wants Full Grown’s furniture to have geometric, midcentury qualities, in contrast with the natural texture of the wood and the bark left in place. “We’re just applying these rules in four dimensions,” says Robinson. “We’re involving time as well.”

The chair itself reveals the time that went into it. The piece of trunk left on the back reveals its age rings, the story of the years it spent in a field in Derbyshire. Emphasizing that time adds to the chair’s aura: “There’s that same quality that you get with wines and whisky, of age and time, and there’s no substitute for that,” says Munro.

In the 11 years since he started this work, Munro, along with Lound, Robinson, and a small band of other recruits, has learned how to work with a tree’s natural inclinations, just as Erlandson once did. Now they know to spiral a lamp’s branches upwards at 45 degree angles, a more natural path for tree growth. Twisted into this shape, a tree will grow about as much in one year as it would have in five years struggling in their older design. The newer chair designs, too, are dictated by the tree’s preferences and require fewer interventions, accommodations, and compromises.

“The tree doesn’t necessarily want to grow into a chair. But at the same time we’re discovering that we can make growing into the chair quite comfortable and reasonable. And actually quite nice for the tree,” says Munro.

The most dramatic intervention they make in the process is sawing a fully grown piece of furniture off its trunk. But even reduced to a stump, as long as part of the trunk survives, these trees will put out new branches, fast and plentiful, to match their strong masses of roots below. It’s a technique passed down over thousands of years of sustainable wood-harvesting in this part of the world. “If we cut the tree down and it just died, that’s pointless,” says Munro. Instead, after the first harvest, the trees grow back quicker and stronger.

Closing in on the goals of his first 10-year plan, it seems possible to Munro that his vision, of growing everyday objects from trees, could become reality. “If we want objects, and we do, then we could quietly make them like this. Every time we reach a parameter, we can figure out a way around it,” he says. “We haven’t gotten to the edge of it yet. I think Ed might be an old man before we get to the edge of it.”

Munro has another timeline in his head, too, this one more speculative. This is for after he is dead, Chris is dead, Ed is dead. It goes out to 5017, as far as his imagination can take him. On that faraway horizon, these techniques are being used to grow more than just chairs and lamps; they’ve helped reimagine the ways we make objects altogether. This might seem like a distant future, but, to the extent that we depend on trees, we already interact with living things that know this time scale. The oldest tree in the world, a bristlecone pine in the California mountains, is 5,000 years old. To reshape the world means believing in the promise of sweeping, far-sighted plans, and understanding that two millennia might only be half a lifetime. It means thinking in tree time.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook