Sold: A 19th-Century ‘Chocolate Museum’ in a Box

It’s now part of a collection of edible books.

Just before Easter, with its bevy of chocolate bunnies, a California bookseller offered for sale a rare box of Parisian chocolate that would have outraged any kid rummaging through their basket. Not your typical package of bonbons, this was instead what antiquarian bookseller Ben Kinmont calls a “chocolate museum in a box,” distributed to schools in the late 19th century to teach children about the origins of French chocolate.

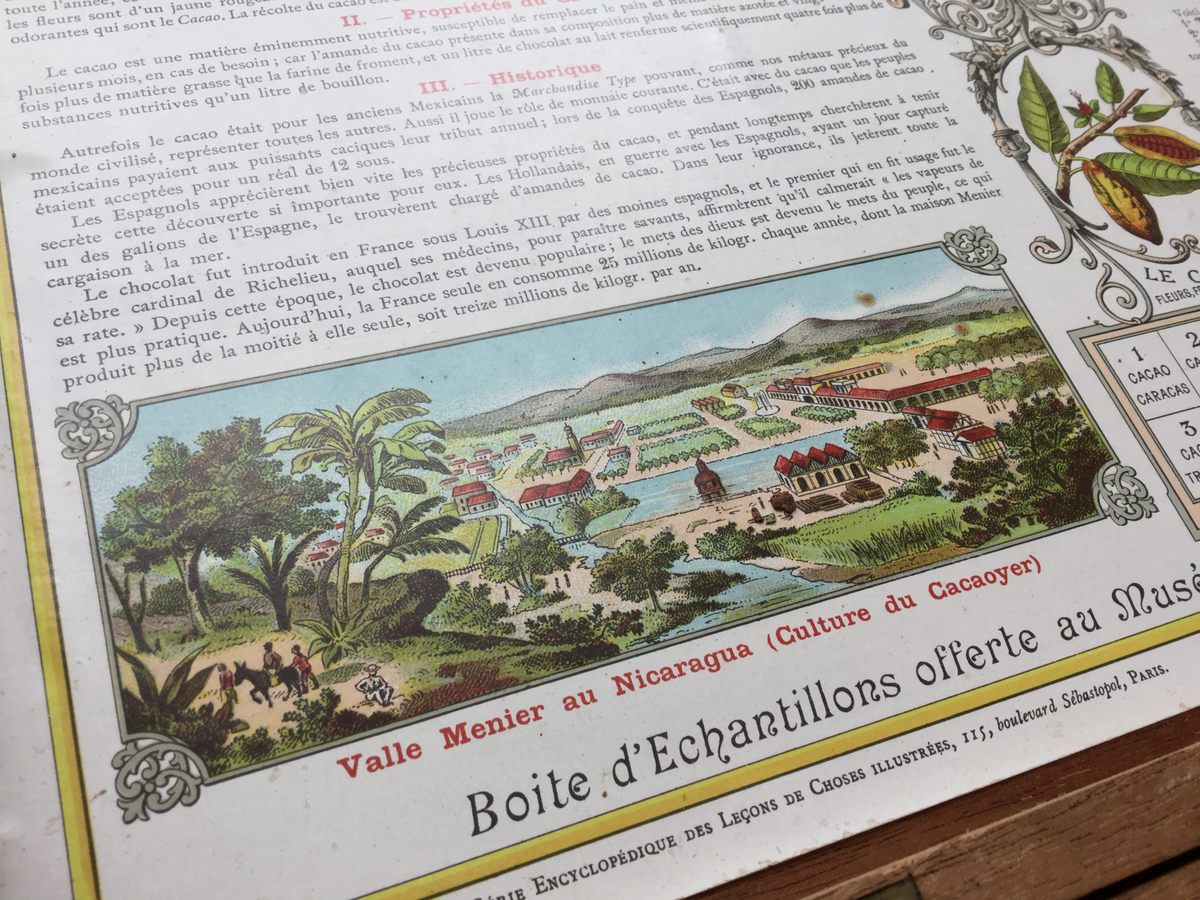

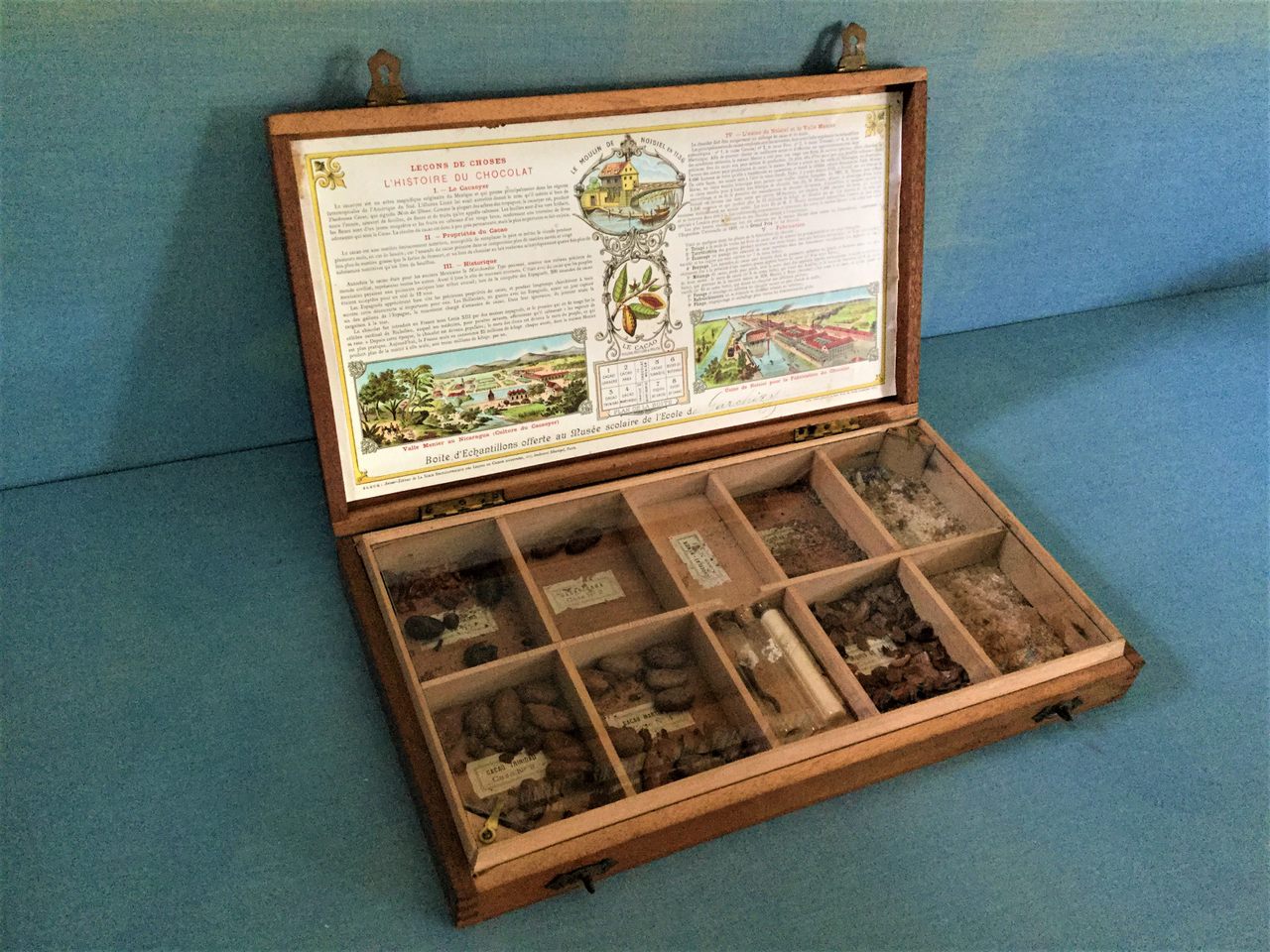

Designed by the famous French company Chocolat Menier in 1889, Kinmont points out that that the box resembles a wunderkammer, a small cabinet of natural curiosities popular in the 17th century. Made of mahogany and bearing an embossed brass plaque, the inside of the upper lid is decorated with a colorful lithograph depicting Menier’s plantation in Nicaragua and its chocolate factory in France.

Inside, there are 10 individual compartments. Seven store the remains of various cacao beans from different regions, one bears traces of sugar, and one holds three tiny glass vials which once contained cocoa butter, vanilla, and an unknown third substance. “The one item which is missing, not surprisingly,” says Kinmont, “was at the top center square area. There was originally a miniature chocolate bar. I can imagine somebody just ate that.”

As Cadbury is to England and Hershey’s to America, so was Menier to France. It was originally founded in Paris as a pharmaceutical company in 1816 by Jean-Antoine Brutus Menier, who may have used chocolate to coat bitter pills. Chocolate was known to be a stimulant, and much like coffee, people argued over its health properties, leaving distribution mainly to apothecaries.

But within the first few decades of the 19th century, large-scale manufacturing of the sweet stuff helped to popularize it. Menier built his own factory town in Noisiel, France, and began issuing bars of chocolate wrapped in golden yellow paper in 1836. By 1893, when they published a booklet to coincide with their appearance at the Columbian Exposition in Chicago, Menier claimed to be the largest chocolate factory in the world, with its own plantations, sugar refineries, steamships, railroads, and 2,000 employees. Though the company was acquired by Nestlé in 1988, Menier-branded cooking and drinking chocolate is still sold today.

It might seem that by sending their boîte de chocolats to schools around the country, Menier was using, if not pioneering, the marketing tactic of targeting the youngest consumers in order to peddle sugar to them—going “right to the source,” as Kinmont puts it. But, he adds, they also took care to present what the raw ingredients looked like, how they smelled, and where harvesting happened. It was this pedagogic aspect that appealed to him when he first came across it. “I’ve never seen another one of the Menier boxes,” Kinmont says, although once he began researching it, he did find two 20th-century American versions, both from the Baker Chocolate Company.

According to Kinmont, the motivation for making these objects and attempting to insert them into the public school curriculum may have had something to do with the increasing industrialization of foodstuffs. Companies such as Menier sought out consumers looking for “an authentic product, one that wasn’t adulterated in some way,” he says, adding, “I think a lot of their outreach to the public was trying to not only increase their market but also just to secure it.”

Menier had an impressive branding team in the 1890s. Apart from the boxes sent to schools, they produced an iconic advertising poster featuring a little girl writing on a wall with a chocolate bar, imagery that was then transferred to all manner of promotional merchandise. At the Paris Exposition Universelle in 1889, Menier dominated with an Arc de Triomphe crafted from 250,000 of its trademark chocolate bars. On that occasion, they also published an illustrated company history, which Kinmont sold with the mini museum for a total of $5,500.

The buyer, Dr. Christopher Fletcher, keeper of special collections at the University of Oxford’s Bodleian Library, says the Menier material caught his attention, because “we have been building up an interesting collection of ‘edible’ books.” A recent acquisition was a volume by the artist Ben Denzer, with pages made out of slices of American cheese. Both may be making an appearance at an upcoming exhibition “looking at the haptic qualities of books,” he says—that is, books with textural elements that go beyond print on a page. But while the chocolate museum in a box may be interesting to touch, nothing inside it likely tastes good any longer.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook