Retracing Ghana’s Old Slave Trail

The story of slavery does not begin with the Middle Passage.

From Tamale, Ghana’s third-largest city, it has taken almost four hours to get here, on a single-lane highway following the White Volta River. Usually it’s under three hours, past shea trees on the sparse, dry landscape, but this time political rallies and visiting dignitaries—including the country’s president—have meant detours and delays.

I’ve made this journey, as I have before, to visit Pikworo. As far as the eye can see, it’s all grass, clusters of stunted trees, rocks, and even more rocks—some brown, some gray like a London sky, pocked with holes and crevices.

The name translates to “rocky area” in Kaseena, the local language. The rocks and boulders are strewn across a sweeping green meadow, the sight of which, after so much brown, is startling. Though it is the rainy season, the morning drizzle is gone and the clouds have given way to sunshine. Nearby, in Nania, a tiny village two miles from Paga, a town on Ghana’s northern border with Burkina Faso, people go about their business—selling, cooking, building a life on the roadside, but this stunningly beautiful square mile of rocks and grass is eerily quiet, save for the chirping of birds.

A small group of visitors and I, led by a guide I’ve encountered on previous trips here, Aaron Azumah, 35, stroll around some of the boulders. Azumah leads us to a couple that have large oval holes in them, like giant thumbprints pressed into the rock. One rather large, rectangular one is filled with water from an underground spring. There’s a sign: “Eating and Drinking Place for Slaves.” Some of the holes, we’re told, were dug by captives, who were forced to dig into the rock with their fingers to create “plates” where a local dish called tuo zafi, made from maize or millet, maybe with cassava, was served. They were eating from the rocks on which they were forced to stand.

All 2019, Ghana has been rolling out the red carpet to celebrities, political figures, and thousands of other members of the African diaspora for what it has termed the “Year of Return,” a 12-month commemoration of 400 years since ships first began to leave its shores, bound for the Americas, heavy with human cargo.

Most of those who have come have spent much of their time touring cities and visiting the castles built on the Atlantic Ocean. These were the last places that their ancestors saw of their homeland. Fewer visitors, however, continue on a reverse journey into the Ghanaian interior, to places such as Pikworo, where the insidious trade took root, where thousands died in the earliest stages of a journey that would, at every stage, claim thousands more lives: the trek to the coast, the slave markets, the Middle Passage, and then more markets, before they arrived at the plantations where those who survived were likely to spend the rest of their lives.

Making this journey in 2019 fills me with sadness. I am confronted with the harsh reality that for many, the brutality of the Atlantic slave trade commenced far away from the ocean, in tranquil villages like this one. Someone who had been captured into forced servitude in the interior might be granted freedom here, or marry someone free or even a royal, so that his descendants might end up free as well, or even in a position of power. But it was a different story for those who made it to the ocean: a generational sentence.

In Pikworo, next to the “dining rocks,” as they’re known, is a small field where a few villagers from Nania have come to give an impromptu musical demonstration. They bang smaller stones onto larger ones sonorously. Azumah explains that this is how the captives here made music, and the villagers boisterously sing traditional songs with roots going back hundreds of years. I don’t understand the words, but they’re supposed to be hopeful, optimistic, looking forward to brighter days. Yet they still call to mind dirges.

Farther afield there is a small rock that resembles a chair. The base is much slimmer than the top, and Azumah explains that this is not a natural occurrence, but rather that for decades ropes have dug into the rock. It’s the “Punishment Rock,” where enslaved people who tried to escape or otherwise misbehaved were lashed, seated, arms behind them, their heads tilted toward the sun.

These accounts aren’t written down in any kind of Western historical text, but rather have been passed down for generations. This is the way of history in this part of the world, where griots and elders can point out which tree or rock has a long story, or a famous or infamous person buried beneath it. It is not the same as historical canon, and therefore inspires some skepticism, but there’s a saying here that appears in various forms: “Until the lion has his historian, the hunter will always be a hero.”

From approximately 1804 until 1845, the local stories say, Pikworo was the base of a mounted slave raider referred to as Bagao, or “bush man,” and his small army. “He was a stranger to this community. When he was embarking on a journey in search of people to capture, he got to this part of the community and realized this particular site was the only place he could keep the slaves healthy and safe from being freed by the local people. It was so isolated,” says Azumah, who is from Nania and has been a guide here since 2006. “He was a black man who never told the people of Nania his origin. Or his name. I can’t tell you his real name, all that I know about is that he was called Bagao.” No one else in the village refers to him by any other name.

Bagao had two lieutenants. Locals are sure one was Burkinabe, and the other from much farther north in Mali. This was how the slave trade worked in the interior; men from elsewhere on the continent—or not so far away—staged raids to capture people from villages and bring them to places like this. In one spot at the edge of the meadow, where a cluster of trees provides soothing shade, there are about eight boulders, the tallest of which provides an unobstructed view for miles. Azumah explains that this was the watchtower used by Bagao and his men.

“So the three were having some kind of army that they would send to the communities including places afar, Niger, Benin. They were all invaders. Many young persons, males and females, strong men, they were at risk. Most times they were captured in the marketplaces, it could be any public gathering, even [in] funeral houses,” Azumah says. Raiders had been known to attack villages on horseback at night and take entire families, and then separate them for a long journey elsewhere, so the captives would be disoriented and lost, discouraging escape. It is said that Bagao brought thousands here to rest before they were forced to walk hundreds of miles down to the coast, bound for the slave ships.

“Some communities, to this day, don’t like seeing horses because that was what was used to raid them,” says James Suran-Era, a Tamale-based French teacher and expert on local traditions. This is one of those stories that seems to echo down through history—even to African Americans today.

This far north, the climate is particularly unforgiving. It’s closer to the Sahara than the sea. Many people died on their marches to and from here, others died after being tied up and left that way for days. There could be 200 people here at a time, and there wasn’t always enough food for them, so starvation loomed. Pikworo today has mass graves demarcated by circles of stones, and locals still bury their dead this way. All the known graves are off to a side of the camp, not far from the punishment area.

The seaside castles and fortresses hundreds of miles away clearly carry the architecture of Europe and the West, but up here the direct presence of Europeans is almost nil. “They never came to the northern part of the country because of the harsh weather conditions,” Azumah says. “It is our own people who started the trade here, being engineered by the Westerners. They provided all the apparatus—let me put it in that sense—though they themselves didn’t come here.”

Pikworo was actively used for about four decades, it is believed, and when the slave trade to the United States and South America slowed and stopped in the 19th century, its stories continued to be told. For over 15 years, the place has been open to visitors as an ecotourism site, though it can be difficult to find, at the end of a winding road away from the already remote village’s commercial strip.

The history is deep and the entrance fee modest, but the location and low profile mean that visitors are scarce. Many come only after hearing of the camp from people at the far more popular tourist site nearby, a pond that houses sacred, surprisingly docile crocodiles. Hundreds come through each year—and more this year—but tens of thousands visit the more famous slave dungeons in the seaside forts that have been the focus of many Year of Return events and publicity. Following this route from end to end is a way to understand that the story of slavery does not begin with the Middle Passage.

The few tourists around have made a great effort to be here. “I really wish more people would go,” says Christa Sanders, the director of Webster University’s Ghana campus. The Philadelphia native has made the long bus trip from Accra more than once, and routinely brings American visitors. “I think it should be a World Heritage site.

“It is critical to be able to go on that journey and be there and understand what the conditions were like before the slaves actually arrived at the final point before being transferred and transported on to the Americas via the Middle Passage,” she adds. “I think being able to hear the people from the local community, through reenacting the music and the songs that slaves at that time apparently sang—to listen to the lyrics—is powerful. You can actually visualize everything that was happening. It just opens up another very difficult, shocking, horrific period of this unfortunate time in history.”

Pikworo today is stunning, natural, seemingly out of time. But this time, like every time I have visited, chills run down my spine. The villagers there today may not have experienced these atrocities directly, but they carry their weight. They all know where the loathsome Bagao—who was killed by in nearby Navrongo—is buried.

Some of the captured individuals who survived Pikworo were auctioned on the spot, but almost all were shackled and forced to trek 200 miles to Salaga, a trading town that historically connected the kingdoms of the Sahel to the commerce of the coast. Kola nuts were a popular commodity there for a long time—to be joined by human lives as a tradable commodity.

In addition to the sun, heat, and lack of food, the captives were forced to carry cargo for their captors, and were at the mercy of bush animals—snakes, scorpions, and more. Some collected fruit or hunted bush meat, or ate whatever little the raiders left them. Many died en route.

Sanders says that it is important for people also to understand what the journey was like on foot. “What we’ve done in an air-conditioned coach bus, people were doing by foot and subjected to the worst of conditions by their own people, as well as the Europeans who came and worked with the locals to capture folks.”

“The journey ended somewhere in Elmina and the Cape Coast castles, but from here [Pikworo] they would move to Salaga slave market … then from that place to Assin Manso, where we have caves and slave wells, where they bathe them finally,” Azumah says.

The Hundred Wells of Salaga, based on a true story, is the seminal work by acclaimed Ghanaian writer Ayesha Harruna Attah. The novel explains how a bath in the pond was the first captives got since being kidnapped by mounted marauders. Then, Attah writes, they were smeared with dollops of shea butter to make them look healthier. There, their fates might diverge. Many would be shackled to trees, half-naked, while buyers haggled over them. Those too weak to be sold were left to die and be picked over by vultures. The buyers then took the others on another journey south—this one 400 more miles along forest paths—to the town of Assin Manso. Today it is a 12-hour road trip. Ghanaian authorities estimate the journey took two to three months on foot.

Assin Manso, like Pikworo, is just about empty. It’s 4 p.m., and the giant gates are locked. But soon enough a guide appears and opens up. Inside is a leafy, calm compound with an open lawn for meditation.

Outside of a bungalow that houses a tiny museum, offices, and restrooms, the compound is devoid of modern buildings. On the yellow walls are four-foot-high murals. One shows men in chains taking a bath in a stream. Another depicts the act of branding, and yet another features a person being punished by being tied up in the sun.

Just 35 miles from the “Big Water,” as the Atlantic Ocean was once known, this was one of the last places on the African mainland where people were auctioned before, mostly, being taken to the New World to be sold yet again. This was also one of the largest stopping points along the various routes used by slavers across the continent. Hundreds of thousands were auctioned here, though it is impossible to know an exact number.

The area around is green and lush—but it was like a dungeon, only out in the open and under the sun. There are two dignified, tiled tombs on the grounds. One is of a lady identified only as Crystal. She was returned from Jamaica. Next to her lies the remains of one Samuel Carson, of the United States. Both had been reinterred in 1998, two people from the diaspora, as a way to not let slavery have the last word.

For Fredara Mareva Hadley, 40, a Brooklyn resident who was a first-time visitor here in summer 2019, places like this—quiet and beautiful, but with so much horror just under the surface—have provided a deep awakening. Hadley had visited Ghana in 2018, but happily decided to come back again for the Year of Return. “I grew up hearing about the dungeons, so as much as anyone can emotionally prepare for witnessing that traumatic experience, I did,” she says. “But I didn’t know the history of Assin Manso, so the beauty of the forest and the sacred feeling there combined with the brutal things that happened there stayed with me.”

There is another gate within the grounds that leads through a horseshoe-shaped concrete entryway, on which “Welcome to Slave River” is painted in bold, black letters. It is yet another idyllic scene on the old slave trail, but as usual nothing is quite as it seems. My guide, Joshua Akabuatse Kwesi, is barely 30, but has an encyclopedic knowledge of the area and its lush vegetation. He leads the way down the path to the water, and tells me that it is the exact path that slaves were led along. Another concrete arch has “Last Bath” painted on it, meaning their last cleansing before the coast, the forts and castles, the white faces, the ships, and more. I’ve noticed as we walk that the path is lined with pineapple trees—and they turn out to be another damnable symbol, a thing of pleasure and sustenance perverted by the slave trade.

“They didn’t have landmarks such as churches and bus stops to really tell you where you were at a particular point so then they had to be innovative,” Kwesi says, of the raiders and their accomplices. “So they planted pineapples from the north to the south to serve as a guideposts. When you see a pineapple, you know you are on the path to Assin Manso. Pineapple trees have been here for over 400 years. As we approach the water, we see some villagers nearby. The river actually splits here and a smaller, shallower stream is denoted “Donkor Nsua,” or “Slave River.”

“This is where the captives took their bath. I really don’t feel comfortable calling them ‘slaves,’ I’d prefer ‘enslaved Africans’ or ‘ancestors.’ This is where they had their last bath before leaving the shores of our country,” says Kwesi. “This is more confined and they can keep an eye on you. You cannot escape.” The area is surrounded by trees on slightly higher ground, so visibility from above was very clear.

After weeks of trekking, the enslaved ancestors did not know that this would be the last place they would wash themselves on African soil. Kwesi explains that they were forced to bathe in the shallow rivulet in groups of 10, still in chains and shackles. “After your bath they made you go through rigorous exercises, such as jumping, to determine your strength. They opened your mouth with obscure devices to count your teeth to determine your age. They smeared you with palm oil or shea butter to make you look attractive and heal your bruises.” Kwesi says.

The juxtaposition of exercise, dental care, and beautification rituals with the literal commodification of humanity is striking.

When large groups visit, Kwesi says, sometimes guides allow them to walk into the waters for symbolic baths. Like most modern activities at these sites, it is a moment of contemplation and tranquility. There is a small museum exhibit, which includes chains and a ball shackle that were found in the river in 2005, and where guests are encouraged to write down their reactions and feelings on the wall. Like at Pikworo, there is a mass grave on site.

“It’s a different shock to the system than the castles because there is little at Assin Manso in terms of buildings and structure, so my mind was overtaken imagining the horrors the forest had witnessed,” Hadley, an ethnomusicologist, adds. The final indignity of Assin Manso, following the auction, was branding: hot iron pressed hard to the dark skin of the captives that would leave a mark to denote that the captive belonged to a particular group of European traders.

The souvenir vendors haven’t seen me in two years and they rejoice. I’ve visited this place, 98 easy miles from Accra along a seaside highway with spectacular views, many times over the years. Being a son of these shores, I consider Elmina Castle and the other fortifications on the Cape Coast a site of pilgrimage.

Unlike Pikworo or Assin Manso, this place has throngs of tourists and the men and women selling bracelets, chains, and other souvenirs come out to greet them, and me. But like those other places, this is a place of uncommon beauty and dark history. Pristine beaches and swaying coconut and palm trees mark the horizon, but they’re not why most people have come.

Rather, they most want to see the rooms and doors of “No Return,” the spaces and portals that led from these castles out to the docks, where people would be loaded onto ships. The first time that many visitors from the African diaspora will confront the most literal horrors of slavery in person will be at the very site where many of their ancestors saw their homeland for the last time.

Elmina is a fishing community that dates back to the 1300s. It is a Saturday afternoon and the boats have been pulled ashore, where their owners are tinkering with things on board. It’s hot and many have been working since dawn.

This all makes the mammoth castle—91,000 square feet—stand out more, still imposing, with fading white walls, yellow roofs, and cannons jutting out all over. It sits on just over two acres, has a moat around it, and has three levels, several courtyards and a smaller church/trading house inside.

The castle’s history of ownership reads as a history of the colonial exploitation of Africa by European powers. The World Heritage Site is 537 years old now. First it was controlled by the Portuguese, who had begun the slave trade in the area three decades earlier, for 155 years. Then it was the Dutch for 235 years, followed by 85 years of English control. For the last 62 years, however, it has belonged to Ghana, and the country has treated it both a tourist draw and a dark part of a vibrant country’s history.

“Elmina” is a corruption of Portuguese for “The Mine,” and here gold and spices from Africa were traded for gunpowder, guns, and more. The local name for the town was Anomansah, or “Inexhaustible Water.” The village is seaside but lagoons and creeks abound. Soon the human trade became increasingly profitable, and the dungeons became a hellish stop—in a long line of them—before the ships carried enslaved Africans to the Americas. There is no evidence that anything other than people were stored in the dungeons.

And that’s where most tours of the castles begin, in the dungeons. Then they go to the churches, the courtyards, the doors and staircases where women were brought to European masters’ bedrooms to be raped—the well-lit and airy quarters where those administrators held court. (Today these places feel ghastly and haunted. There had been joy here among certain people, but it’s hard to imagine.)

Many visitors are then shown the courtyard where stubborn slave women were left out in the sun, chained to cannonballs, as an example to other African women who refused. Some women who were repeatedly raped got pregnant, and their children were raised and educated in the castle, where they were taught to be interpreters. At some point some stone houses were built for the mistresses and their children. Today, in Elmina, many Ghanaian families have surnames such as Vroom, DaCosta, Yankson, and Pieterson.

As probably the most-visited site in Ghana related to the slave trade, Elmina Castle sees tens of thousands visitors yearly, and many more this year, it seems. In the dungeons, chatter among visitors soon gives way to gasps, reflection, and ultimately stunned silence.

I walk through these spaces with Ato Ashun, author of Elmina: The Castles & The Slave Trade, the curator for the 42 forts and castles along the coast that were used in the slave trade. “Women and children were chained together for months with no other place to menstruate or use the toilet,” Ashun says. “In the life of a captive, life never got better.”

Somehow, the smell seems to remain, a powerful stench in the female dungeons that knocks visitors for a loop. On average, according to Ashun, captives spent two months chained in these dungeons. Every time that I’ve been there, on average about once a year for the last decade, the stench is the same.

The indignities didn’t stop there. In the female areas, more rapes, assaults, and vicious beatings by European soldiers were commonplace. In the male holding areas, men and boys were chained together. Resistance was not tolerated and examples were made of the stubborn. Outside of beatings, they could be isolated in a dark cell with just a sliver of light for weeks. If someone died in the dungeon, his body would be left with the living for a while, Ashun says.

We see groups visiting from the United States, and another from South Africa. There are a lot of them, and for someone who has visited this place many times, it is thrilling to see so many people experiencing it. It’s an international group with a diversity of races. All are sobered by the experience.

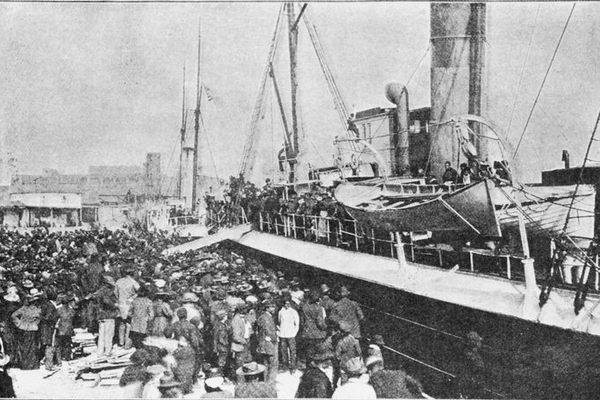

The entire trek through the country from Pikworo and Salaga to Assin Manso took the captives, who survived against all odds, to a singular point—a “Door of No Return.” It is actually a tiny gate, barely large enough for the average person today to squeeze through.

The trek and the months in the dungeons, awaiting the boats, had weakened the enslaved people. Those who made it here were so gaunt and reduced that they could pass through the gate easily. They were then put on small boats that carried them to the ships.

Today, the ocean has receded and the door opens to nothing. Some visitors poke their heads out and quickly pull back in. It’s an extremely dark room, empty save for bouquets of flowers or liquor bottles brought as inadequate memorials, but the place feels stifling. The most striking visual difference between then and now is the visitors I see around me, the descendants of people who passed through places like this. The guides say that most respect a moment of silence here, and then vow “Never Again.” It’s barely even that long before most who visit here just want to get out.

You can join the conversation about this and other stories in the Atlas Obscura Community Forums.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook