The Badass Female Gladiators of Ancient Rome

Gladiatrices were fierce athletes who drew crowds of thousands.

On a clear, crisp morning in 80, Rome was abuzz. For the last few years, it seemed the gods had cursed the empire. In 64, a six-day fire ripped through the capital. Around 78, a deadly plague devastated locals. In 79, the southern city of Pompeii was buried beneath ash and fire. But all of that was about to change.

Immense crowds gathered at the gates of the newly inaugurated marble-encased Flavian Amphitheater. Emperor Titus had declared 100 days of brutal, free, blood-soaked games. Finally the Romans had something to look forward to. In the light of the sun’s morning rays, beast hunters wetted the arena’s sandy floor with the blood of thousands of exotic animals. The next few hours were filled with executions, performances, and the distribution of gifts until afternoon fell and the empire’s most popular sporting event began: gladiatorial combat. But it was not only burly, bare-chested men that faced off before some 50,000 spectators: In these games, women also competed.

Rare, thrilling, and highly contentious, female gladiators fought in arenas across the empire for some 200 years. While male gladiators are one of ancient Rome’s most enduring legacies, the history of female gladiators is extremely fragmented. Our knowledge of these women warriors is gleaned from only two visual representations and a handful of references from Roman historians. Still, their existence is undeniable, challenging historic and modern assumptions about Roman women.

Gladiatorial games probably started in pre-Roman communities, and in 264 B.C. the Romans first adopted the sport primarily as funerary entertainment. Forcing prisoners of war and slaves to fight at gravesites was considered a way to honor the dead, says Kathleen Coleman, a classics professor at Harvard University.

Harnessing the sport’s growing popularity, politicians started organizing gladiatorial games in Roman forums. Eventually, gladiator arenas were built across the empire. “By the time of the building of the Colosseum, gladiatorial combat had become a ritual form of entertainment, only occasionally provided and therefore highly anticipated,” says Coleman.

Female gladiators likely emerged between 40 B.C. and 19, a period of great change following a civil war and Rome’s transition from republic to empire. “After Caesar’s murder in 44 B.C., there was a period of social rules not applying to the same degree, in which women generally enjoyed more prominence, and there was an increase in spending on entertainment,” says David Potter, a professor of classics at the University of Michigan.

In 19, the senate issued a decree prohibiting upper-class men and women from participating in gladiatorial games. While historians are divided on whether the decree was in reaction to women registering as gladiators or just a preventive measure, one thing is certain: It didn’t stop women from appearing in the arena over the following two centuries.

Although many female gladiators were likely slaves, Roman sources do write, with no small degree of reproach and horror, of noblewomen who picked up the sword. Those who entered the arena willingly likely needed a degree of freedom within their day to train, suggesting that they came from more privileged backgrounds, says Potter. “There’s a large range of explanations, depending on time and place, but prominence, money, and social protest are reasons for why a woman would willingly want to be a gladiator,” he says.

According to Roman sources, emperors such as Nero and Domitian were fond of throwing lavish celebrations featuring female gladiators as novelty acts. The Roman historian Cassius Dio wrote of a days-long festival Nero held in honor of his mother in 59 where upper-class men and women “drove horses, killed wild beasts, and fought gladiators, some willingly and some sore against their will.” Roman historian and politician Tacitus referred to Nero’s female gladiators as feminarum, a term reserved for upper-class women, writing that “many ladies of distinction, however, and senators, disgraced themselves by appearing in the amphitheater.”

In 66, Nero sponsored more gladiatorial games featuring Ethiopian women, wrote Dio. And in 88, Emperor Domitian held games that again featured female gladiators, wrote biographer and historian Seutonius.

Sources also wrote of venatrices, female beast hunters, appearing in the Colosseum’s 100 days of opening games in 80. Venatrices took down stags, boars, and even lions with spears and bows, says Potter. Whereas female gladiators likely fought other women to first blood in single combat, explains Potter. Contrary to popular belief, fighting to the death was rare in gladiatorial games: Sponsors considered gladiators expensive, long-term investments.

Even though many Romans disapproved of female gladiators, people went wild for them in the arena. “We do know that some of the [female gladiator] fights took place in mid-afternoon, and that’s not the time for the novelty acts or the comedies or the executions,” says Philip Matyzask, an author, historian, and professor at the University of Cambridge. “That’s the time for the premier gladiator fights. So they were treated as serious professional bouts.”

Based on our knowledge of male gladiator attire and a surviving marble relief depicting two female gladiators, female fighters likely wore a loincloth, armored sleeves, and greaves and used swords and a large shield in the arena. Unlike male gladiators, women probably fought without helmets, so spectators could clearly identify them as women. Female gladiators also went into the arena topless or with one breast exposed, a reference to the mythological Amazon warriors.

This was a sharp deviation from the attire of Roman women, who wore a stola that covered them neck to toe, says researcher and author Alfonso Manas. While male gladiators also fought shirtless allowing the crowd to see any drawn blood, semi-nude women fighting before a primarily male crowd held a sexual undercurrent, says Manas. “Roman men liked watching spectacles of female gladiators so much because Roman women were not expected to perform that role,” says Manas. “They were educated to be modest, peaceful, good wives.”

Manas also notes that there’s no Latin word for a female gladiator. “How a culture names things, the words they use to name realities, is very important, and that they never called those women ‘gladiators’ is of paramount importance,” says Manas.

Contemporary historians often use the term gladiatrix to refer to them, but it’s a modern construction that wasn’t used in antiquity. The closest term is ludia, but even that was generally used to describe the lover or wife of a gladiator. When women first started appearing in the arena, however, the term was also applied to them, says Manas.

Roman society was highly stratified by class, and entertainers such as gladiators, prostitutes, and actors were all lumped into the infame, a rank lower than slaves, says Matyzask. “It’s a lifelong stain on your reputation. So even somebody who voluntarily signs up to be a gladiator is basically chucking their social reputation into the trash can,” he says. If a female gladiator was of highborn status, she shed all respectability in the eyes of Roman society and became an infame the moment she stepped into the arena.

“Female gladiators must have been very infrequent and very transgressive. If you think of the word virtus, courage, which is what gladiators embodied, the root of that word is Latin for man, and so by definition, women can’t display it,” says Coleman. “So when you have women fighting bravely in public like that, it was very transgressive. It must have shocked and thrilled the Romans simultaneously.”

There is plenty of evidence regarding the lives of male gladiators and more than 1,000 of their names have been recorded in literature, mosaics, and tombstones, says Manas. Evidence for female gladiators, by comparison, is scarce. “Male gladiatura [a term for gladiatorial fights] created individual stars—Spartacus and Spiculus—whilst female gladiators were anonymous individuals, interchangeable pieces that were replaced with others,” says Manas.

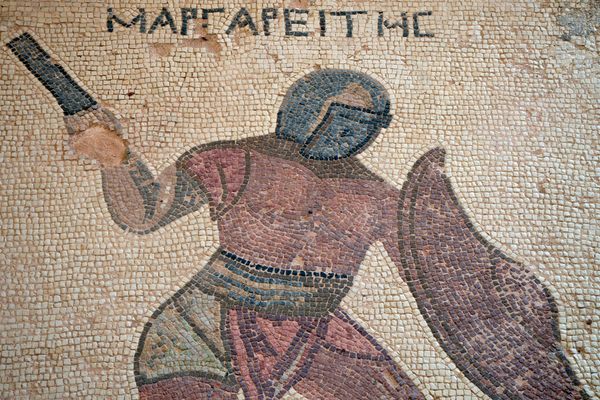

The only evidence we have for female gladiators’ names is a marble relief from Halicarnassus (modern-day Bodrum, Turkey) housed in the British Museum. Dating to the second century, it shows two female gladiators, Amazon and Achilia, in combat. Both are depicted topless with raised swords and minimal armor and are likely reenacting the mythological battle between Achilles and the Amazon warrior Penthesilea. This relief is one of just two depictions of female gladiators known to scholars.

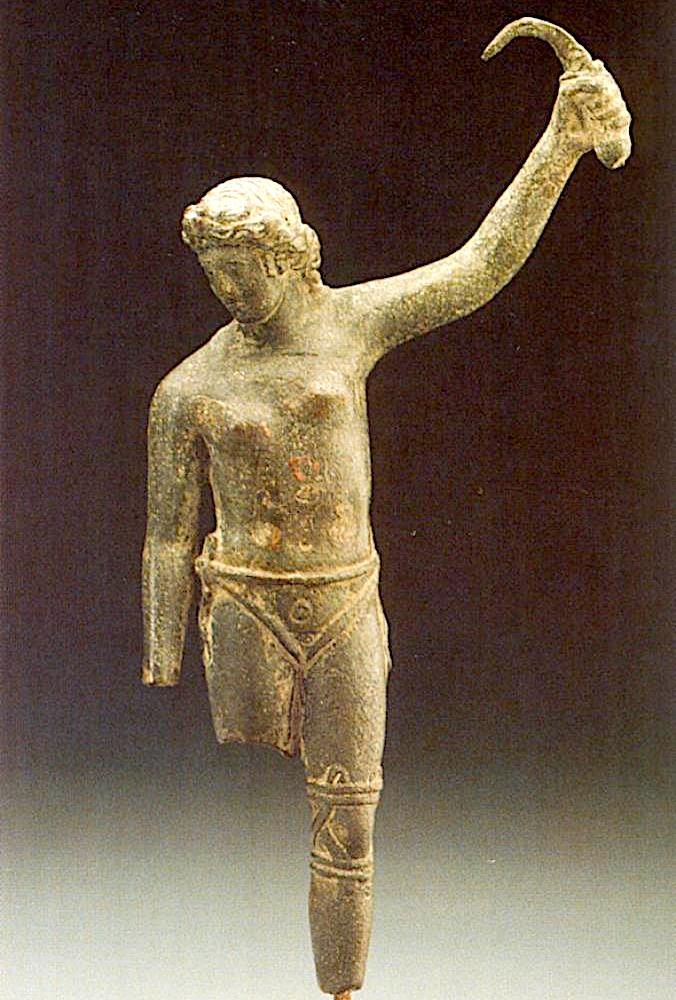

The second is a statuette housed in the Museum für Kunst und Gewerbein in Hamburg, Germany. Long believed to be a woman cleaning herself with a bathing instrument, Manas identified the figure as a female gladiator in 2011.

“It was a sensational discovery that shocked the academia because it is the sole statuette depicting a female gladiator,” he says. Depicted topless and only wearing a loincloth, the statuette holds a sica, a short sword, in a triumphant pose.

In 200, Emperor Septimus Severus banned female gladiators from competing in the arena after a crowd jeered and behaved rudely while watching female athletes. At the time, interest in gladiatorial games had already started to decline. By 450, gladiators ceased to exist, mere decades before the thousand-year-old empire collapsed.

The very existence of female gladiators complicates the understanding of Roman gender roles. Many believe Roman women were docile, modest, meek, and subservient to the men in their lives. But “Roman women wielded much more influence in society than many people out in the public think,” says Coleman. Roman women could be independent benefactors (funding the construction of buildings, temples, and social programs), own property, and divorce their husbands.

“I think we develop a better understanding of our own culture by close study of another,” says Potter, and studying female gladiators illuminates the “latent sexism in the way we view women,” both today and in antiquity.

Rome’s female gladiators are just one offshoot of women’s long, often-forgotten history as warriors. “Women have fought in nearly all conflicts and wars throughout history, from the war of Troy until today,” says Manas. Rome’s female gladiators were the women warriors of their time—redefining societal expectations of what women were and are capable of.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook