The Inspiration for the Graham Cracker Was a Preacher Obsessed With ‘Curing’ Masturbation

He believed in eating like the original vegetarians: Adam and Eve.

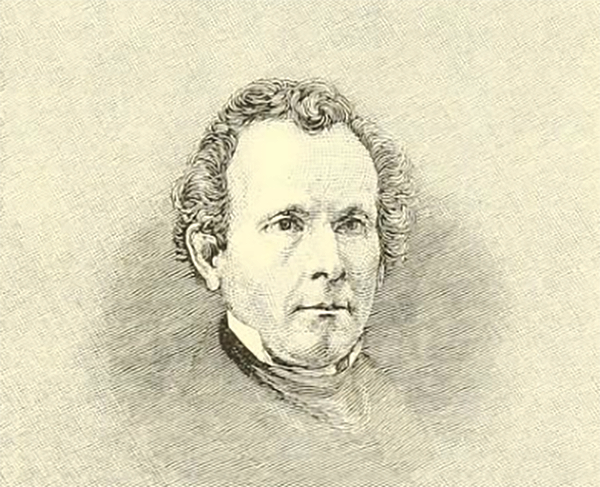

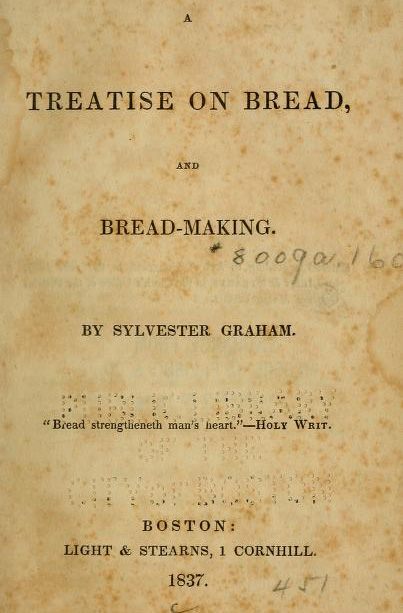

In 1837, Reverend Sylvester Graham, the man who gave us the graham cracker, published a book titled A Treatise on Bread and Bread-Making. It began with the following sentence: “Thousands in civic life will, for years, and perhaps as long as they live, eat the most miserable trash that can be imagined, in the form of bread, and never seem to think they can possibly have anything better, nor even that it is an evil to eat such vile stuff that they do.”

The reverend’s sentiments may sound like the ravings of a mentally disturbed baker, but in 1837, A Treatise on Bread and Bread-Making was a runaway hit. Graham was a star preacher within the temperance movement, and championed a strict, meat-free diet modeled after the Bible’s original vegetarians: Adam and Eve. Graham’s diet called for consuming only plants, water (no alcohol), and other “pure” items one might find in the Garden of Eden. Chief among Graham’s concerns was whole-grain bread, made from home-ground wheat, which he viewed as the cornerstone of modern, impure lifestyles. A Treatise on Bread and Bread-Making inspired the production of so-called graham flour, graham bread and, most famously, graham crackers.

Graham claimed his diet was more than simply a way to stay healthy—he viewed it as imperative to stopping the moral collapse of humanity. He believed that “gross and promiscuous feeding on the dead carcasses of animals” would degrade man down to the “bone and marrow,” rendering society “odious and abominable.”

But Graham’s holistic approach to self-improvement went far beyond food. It included mandates to exercise, bathe regularly (a radical idea at the time), and, most importantly, abstain from sex except in cases of reproduction. To Graham, our thoughts and morals flowed from our primal, bodily functions. Grahamism espoused that chaste sex and food consumed in its purest form were essential to living a healthy and spiritually fulfilling life. There was also, according to the reverend, a link between the two: living by the Graham diet would stop all sinful sexual urges. For the young man whose impure diet led him to commit “the worst of all venereal sins … self pollution,” something as simple as a graham cracker could prevent masturbation.

The reverse was also true: a bad diet would not only deteriorate health but encourage sinful sexual behavior. As he noted in his 1848 text, A Lecture to Young Men on Chastity, consuming a delicious steak dinner with wine could “increase the concupiscent excitability … of the genital organs” and lead to all sorts of horrific “sexual excesses.” These excesses included lascivious thoughts, wet dreams, sex outside of marriage, sex within marriage but without the intention of procreation, and, most dreaded of all, masturbation. Roughly half of A Lecture to Young Men on Chastity is a grisly, organ-by-organ account of how these food-induced “sexual excesses” destroy each and every part of the body, including the stomach, intestines, heart, lungs, liver, kidneys, nervous system, brain and, of course, genital organs.

According to Graham’s theories, if a 19th-century man woke up in the middle of the night to discover that he’d had a wet dream (which was completely his fault, because he ate processed bread), he might experience a “hemorrhage of the lungs, and gushing of blood from the mouth and nostrils.” But of all the sexual excesses, Graham was most obsessed with masturbation. A Lecture to Young Men on Chastity returns to this topic, at length, a total of 33 times, obsessively detailing all the gruesome consequences of “self-pollution.” Masturbate long enough, and your eyes will “fall back into their sockets, and perhaps become red and inflamed.” You may even go blind. This all could be avoided, of course, if one adopted “a plain, simple, unstimulating, vegetable and water diet.”

Graham’s theories may seem ludicrous—Pornhub has yet to blind anyone—but his adherents had some reason to believe him.* In the 19th century, during the syphilis epidemic, sex quite literally caused disease, insanity, and death. Before germ theory evolved, medicine did not have an explanation for syphilis, and the majority of doctors and scientists embraced the idea that sex acts themselves (as opposed to microorganisms) were responsible for disease. Graham claimed that his diet prevented cholera, and when cholera hit New York, in the summer of 1832, many followers of his strict regimen avoided the disease altogether. Or at least that’s the perception that Graham created. Graham obsessively documented their testimonials in his 1839 text Lectures on Science and Human Life, a 700-page opus devoted to defending his theories. The account of one Evander D. Fisher effectively summarizes the urgent tone and visceral content of these endorsements: “We adopted … living on simple vegetable food … I was among the dying and the dead, and assisting in laying out and putting into their coffins at least a dozen dead bodies of those who had died of cholera, yet neither myself, wife nor sister, had the least premonitory symptoms of cholera, nor any other illness during the whole season.”

Cholera was the best thing to happen to Sylvester Graham, as a frightened public latched onto his ideas. Grahamites, as his followers came to be known, mobbed his lecture series in New York and New England—often as many as 2,000 people attended. Graham put on quite a show, and he was known to pack as much gore, sin, and sex into his sermons as possible. But though his fire-and-brimstone style excited the Grahamites, it angered his enemies: butchers, who promoted “gross and promiscuous feeding on the dead carcasses of animals,” and bakers, who produced “miserable trash” disguised as bread. When Graham visited Boston in 1837 to promote A Treatise on Bread and Breadmaking, butchers and bakers nearly rioted outside the packed lecture hall.

Despite his popularity, Graham never grew rich off his ideas. He never branded or sold his particular type of graham flour; he was far more concerned with saving souls than starting a business. (And Graham never would have approved of adding sugar to make graham crackers tasty, as The National Biscuit Company—or Nabisco as it’s known today—did in 1898.) He made his ideas available to everyone, and as a result, the Graham diet lived on well past his death in 1851. Grahamism eventually disappeared toward the end of the 19th century, but Graham’s influence was lasting. As historian Richard H. Shryock noted in his 1930 publication Sylvester Graham and the Popular Health Movement, “A century after Graham first made his appeal, his preachments have begun to be practiced and today, at least part of the population, apparently eat less and select their food with greater care than did their fathers. People nowadays are seekers after roughage and the whole grain in cereals. They worship fresh air and sun-tan, and the bath room has become the very symbol of American civilization. Verily, Americans have been ‘physiologically reformed.’”

Shryock’s observations still ring true today; Graham was a leader of the diet reform movement of the early 19th century, and many of our contemporary attitudes toward food and eating can be traced back to his theories. If it were not for Graham (and his health obsessed peers), the concept of the modern diet may not exist. As historian Martha H. Verbrugge notes in Healthy Animals and Civic Life: Sylvester Graham’s Physiology of Subsistence, Graham was at the forefront of “a variety of medical and lay reformers [who] advocated new codes of dietary and sexual behavior, arguing that self-improvement … was the fundamental agent of social betterment.”

Ultimately, Graham’s greatest legacy is not the graham cracker, but the concept of a diet and the link he forged between our spiritual existence and eating. Today, the diet has supplanted religion as a popular method of addressing our deepest existential worry: the problem of death. Through diet and exercise, our mortal bodies can stave off their inevitable fate; salvation is possible when there is a StairMaster. It may be easy to render Sylvester Graham as a comic character—the Jesus-freak vegetarian who invented graham crackers to stop masturbation—but there is a reason his concept of the diet has endured. Graham tapped into our greatest mortal fears and presented a solution. And it makes sense that a preacher would merge our conceptions spirituality and corporeality—making the body a temple. Though many Americans have since abandoned Jesus in their quest for their “best self,” we still seek salvation through our stomachs. You are, after all, what you eat.

*Correction: This post previously described Sylvester Graham as a doctor. Although he wrote extensively about medicine, he was not a doctor.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook