We’re All Citizens of the Garbage Patch State

An Italian artist has created an imaginary homeland for all of our plastic waste.

Picture a car. And another, and another, until you get to 1.5 million. Okay, that’s not so easy to picture, but it’s roughly how much plastic we put into the ocean each year, around nine million tons, enough to cover the entire island of Oahu, more than ankle-deep.

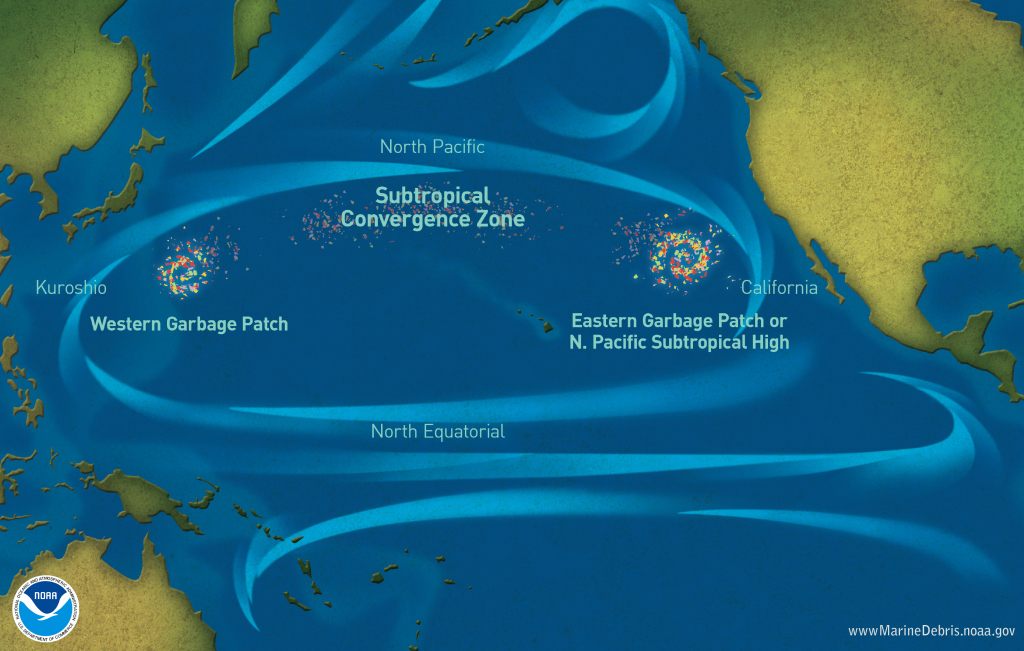

In the oceans, all of this persistent debris gets famously stuck in gyres, or circular currents, to form gigantic vortices of trash that have become known as garbage patches. So far, five have been found in the Pacific, Atlantic, and Arctic.

“It was back in 2011 or 2012, I don’t remember exactly, but it was around that time that I first heard of garbage patches, islands of trash that float around in the ocean,” says Italian artist Maria Cristina Finucci. “But when I looked them up online I realized that they looked nothing like actual islands.”

Indeed, while the gyres bring plastic together they don’t exactly adhere them, so instead of a three-dimensional island they are more like massive expanses of sea-plastic soup. Water and sunlight break much of the material down into miniscule particles, smaller than a hundredth of an inch. Those that are visible at all look like “confetti” or “cupcake sprinkles,” according to oceanographer Charles Moore, who first described one of the patches in the Pacific in 1997.

The impact of the patches also doesn’t stay in the gyres, since the particles travel all over the marine ecosystem, and end up inside seabirds and fish and mammals, and even, as recently discovered, microscopic worms seven miles below the surface.

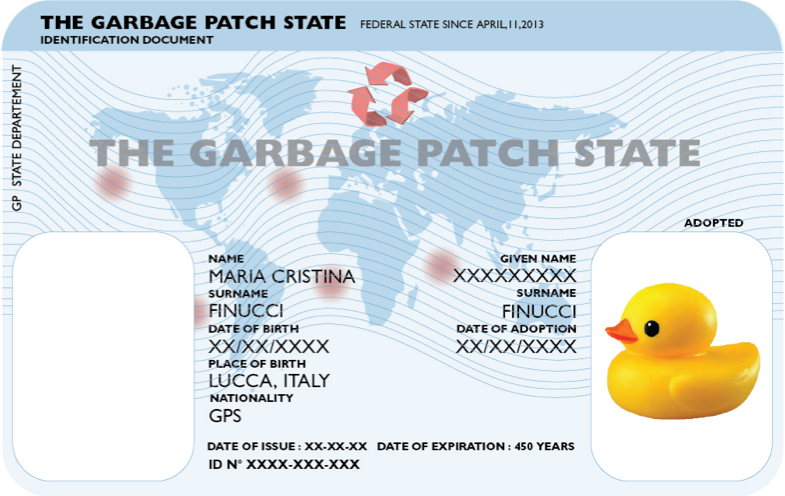

“The problem is that garbage patches are a very real and urgent issue but we cannot see them,” Finucci says, “so it’s hard for people to realize they are there.” So since 2013 she has worked to make these invisible islands a little more prominent. “People often imagine places they have never been thanks to photos, for sure, but also thanks to symbols or clues like flags, passports, or postcards.”

So Finucci has started leaving a trail of clues to a mythical land she calls the “Garbage Patch State”: an official state declaration signed at the Paris headquarters of UNESCO, a flag, an embassy opened in Rome in 2014, and postcards available from the project’s website. During the state’s “official” events, Finucci brings two things: a booth where people can get a Garbage Patch State passport, and haunting art installations made of millions of plastic bottlecaps. The first one appeared at the Venice Biennale in 2013—a giant “snake” in the beautiful courtyard of Ca’ Foscari University.

Plastic was invented by British metallurgist Alexander Parkes, who was trying to come up with a material that could be easily molded while hot. His new material, derived from dissolving cellulose nitrate in alcohol, was patented as “Parkesine” in 1856. Parkes couldn’t have known it, but we’ve since become a civilization of plastic. In 2015 we manufactured 380 million tons of the stuff, and the total grows by 8.4 percent a year.

While we use materials such as steel and cement to make things of some permanence, such as roads and buildings, most plastic is more or less designed to end up as waste. A few months ago, Rolan Geyer, and industrial ecologist at the University of California, Santa Barbara worked with two colleagues to count and sort all the plastic we have made since mass production began in the 1950s. They found that most of it, a whopping 60 percent, has been discarded into landfills, or in natural environments, including the oceans. This waste, it has been posited, might someday represent a geological indicator of the Anthropocene.

According to Geyer, the “culture of disposability” goes back to the unfortunate marriage of single-use packaging and plastic mass-production. “Single-use containers were becoming more and more popular in the early 20th century, but were initially made of paper, glass, and metal,” he says. “And when all common polymers started being mass-produced after the end of World War II, single-use containers were a big application for them.” Its legacy is the age of the K-cup, all nine billion of them we throw out every year.

“So one solution would be a return to multiple-use containers along the entire supply chain, but that would involve big behavioral changes,” Geyer explains, adding that governments could regulate single-use plastics. More than 30 nations—real ones, not imaginary—have recently banned or regulated the use of plastic bags, including Kenya, Tunisia, and France.

But Finucci believes this political response is too slow, so she appears at key international meetings, the Garbage Patch State in tow. “In Venice I put up an installation [at the BLUEMED conference in 2015], a spiky snake that was intended to show the planet’s anger towards politicians,” she says, “and during COP21 in Paris I had the same thing but this time it was bright red, as it was even more enraged.”

Asked if world leaders appear to notice the giant angry plastic snake, she says, “They do, but oftentimes they just go by.” But during COP21 (the United Nations Climate Change Conference, 2015), Finucci got past security and approached then U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry. She introduced herself as the “President of the Garbage Patch State.” Kerry, visibly confused, asked, “The President of What?” before the artist was invited by security to take a step back.

Finucci’s latest manifestation of the state is a look into its imaginary future with an evocation of what its ruins might look like. The tiny island of Mozia, just few miles off western Sicily, contains Phoenician, Greek, and Roman ruins. “I asked myself what would archaeologists find 2,000 years from now?” Finucci says. “Well, not the marvelous ruins that we see now in Mozia but rather a hell of a lot of plastic.”

So she took more than five million plastic bottlecaps and turned them into ruins—from multistory buildings to dolmens—all at the same scale as the actual Mozia ruins. Except they make a particular pattern when see from above.

“I imagined the future archaeologist walking around and being puzzled: What is this all about?” she says. “But once back on their spaceship—I imagine they will have spaceships, of course—they would look down and see that the relics make up the word ‘HELP.’”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook