The Spooky Science of Why Mirrors Can Freak Us Out So Much

We reflect on what these shiny surfaces reveal, from the curse of Narcissus to an experiment you can try at home—if you dare.

Beyond the Las Vegas Strip’s dazzling lights, something darker awaits Sin City visitors who venture into celebrity ghost hunter Zak Bagans’s Haunted Museum. There, the spooky memorabilia ranges from Ted Bundy’s glasses to fragments of Charles Manson’s bones, scraped from the incinerator after his body was cremated. There’s also a rather plain-looking mirror, about two feet tall and shaped like a tombstone. Bagans has said that, of his entire collection, it’s one of the things that unnerves him the most.

Allegedly, the mirror once belonged to Dracula actor Bela Lugosi. The story goes that he used it in occult attempts to contact his deceased wife, but instead invited something unwanted and otherworldly. The mirror’s next owner was murdered and, in the years that followed, subsequent owners have reported seeing a dark entity reflected in it. Some even claim to have been attacked, waking from uneasy dreams covered in scratch marks.

The Lugosi mirror is hardly the first reflective surface to scare up a chilling story. Legends about the powers of mirrors go way back, according to Binghamton University folklorist Elizabeth Tucker, who focuses on the supernatural. “Narcissus is about the earliest clear story connected to seeing a reflection,” she says. The ancient Greek myth tells of a handsome young man who became so enamored of his own face reflected in the water that he wasted away gazing at himself.

The stories didn’t stop there. Ancient Romans believed that mirrors had the ability to trap the soul; they also believed that it took seven years for the soul to regenerate itself, which is where we get the superstition that breaking a mirror results in seven years’ bad luck. And over time, mirrors’ supposed powers expanded, including fortune-telling.

“It’s in the medieval period that we start to have stories of deliberate summonings using reflective surfaces, either mirrors or a bucket of water,” says Tucker. These rituals appear to be the earliest use of reflections in “love magic.”

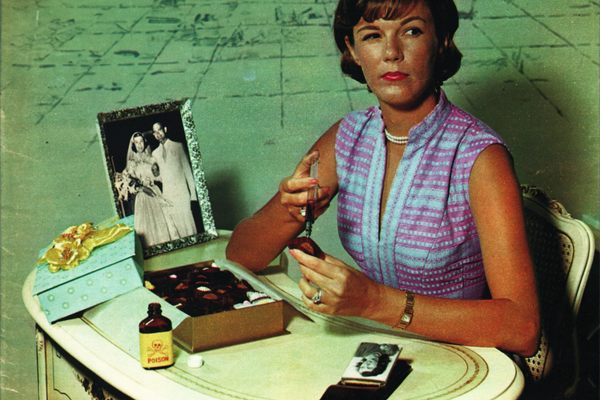

“If you do it just right, you summon up the face of the person who is going to be your beloved,” Tucker says. This superstition survived well past the Middle Ages. Halloween greeting cards from the early 20th century depict young women peering into mirrors, alongside rhymes such as “On Hallowee’n, look in the glass/ Your future husband’s face will pass.” (It wasn’t all lighthearted: If the woman was destined to die before she married, she would apparently see a skull.)

More recently, Tucker has noticed a shift in this narrative. Mirror-gazers have become less interested in summoning the face of their beloved and more likely to try to bring forth something scary. One of the most popular of these recreational fear-seeking rituals is “Bloody Mary,” in which chanting the spirit’s name is said to make her appear in the mirror.

Strange faces in the mirror are also a common horror film trope, showing up everywhere from the Candyman movies to Disney’s brief foray into psychological horror, The Watcher in the Woods. YouTube is full of amateur filmmakers who claim to have captured an evil onlooker in the looking glass. And in 2010’s Oscar-winning thriller Black Swan, an often-subtle mismatch between the main character and her reflection is used to heighten the feeling that something is awry. Mirrors are also a staple of the haunted house industry, says Leonard Pickel, who’s been designing haunts for more than 40 years.

“A subconscious mind, no matter where it’s at, is always looking for danger. It’s always looking at stuff and trying to decide whether it’s safe or a threat,” says Pickel, the owner of haunted house design company Hauntrepreneurs. “When the brain can’t decide whether it’s friend or foe, that’s the creepy feeling that you get, when the hair stands up in the back of your neck.”

While we’re primed to look for potential threats in anything unexpected, it’s especially jarring from a psychological standpoint when the thing that doesn’t match our expectations is our own reflection. “We’re all experts in looking in the mirror and seeing ourselves,” says Joanna Mash, a PhD candidate in psychology at the University of Hertfordshire in England. “You have a very well-established expectation of looking into the mirror and seeing your own face.” Having something you know so well, that’s so intrinsically connected with your sense of self, be replaced with something that’s not quite right, not quite you is, as Mash puts it, “gonna be pretty scary.”

Seeing the wrong reflection doesn’t just happen in Hollywood and haunted houses. Our brains are actually quick to misinterpret what we see in a mirror, often scaring us silly in the process. Twenty years ago, University of Urbino psychologist Giovanni Caputo was studying dissociative identity disorder (formerly called “multiple personality disorder”), a condition in which people’s identities are split into different personas, often as a coping mechanism for extreme trauma. One experiment, intended to examine these patients’ sense of self, involved placing eight mirrors around the study’s participants. The subjects noted that, under low light, the reflections of their faces seemed to change. Caputo was intrigued. “I concentrated my scientific efforts on this new phenomenon. This was truly a case of serendipity,” he says.

In 2010, he published the first description of what’s become known as the strange-face illusion. He showed that when people stare into a mirror under low lighting, they will often see their faces warp and change. Some watch their own facial features distort, while others see the visages of deceased loved ones or even monsters. (Subsequent experiments have shown that you don’t even need a mirror for the strange-face illusion to occur; you can also focus on another person’s face, or even a mask.)

These frightful visions aren’t the result of anything supernatural, however. The process of taking in information with our eyes and interpreting it with our brains is like a game of telephone, and the messages can become garbled if the lights are too dim and we’re staring too intently.

Mash has conducted strange-face experiments and even experienced the illusion herself. “I saw distorting features, and I saw faces that almost weren’t my face, but I didn’t get to the point of seeing completely new strange faces,” Mash says. She thinks that people who are better at focusing their eyes on one spot tend to see more. “I was quite disappointed, I felt like I’d been short-changed,” she jokes.

But while Mash had been hoping to see a more dramatic manifestation of the strange-face illusion, she adds, “When I’ve run this experiment, some people do come out quite freaked out about the fact that that has happened. And I think it just demonstrates to people, fundamentally, that our visual experiences are constructed in our mind, and they don’t actually directly represent what we’re trying to see.”

Caputo suspects that the strange-face illusion is at the heart of persistent haunted mirror legends. It may even explain the enduring fascination with Bela Lugosi’s allegedly haunted looking glass—despite the tale surrounding it getting warped and distorted over time. For starters, as reported in Skeptical Inquirer, Lugosi never showed an offscreen interest in the occult. He also never lived in the same house as the mirror. Hollywood lawyer Peter Saletri did live there, however, and was brutally murdered in 1982 in a case that remains unsolved.

Ultimately, what these mirrors really reflect may be humans’ longstanding superstitions and fears, rooted in how our brains process visual information, when we see something that’s not quite right.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook