The Dark History of Hawai‘i’s Iconic Hand Gesture

The ‘shaka’ or ‘hang loose’ gesture likely originated from island plantations’ brutal working conditions.

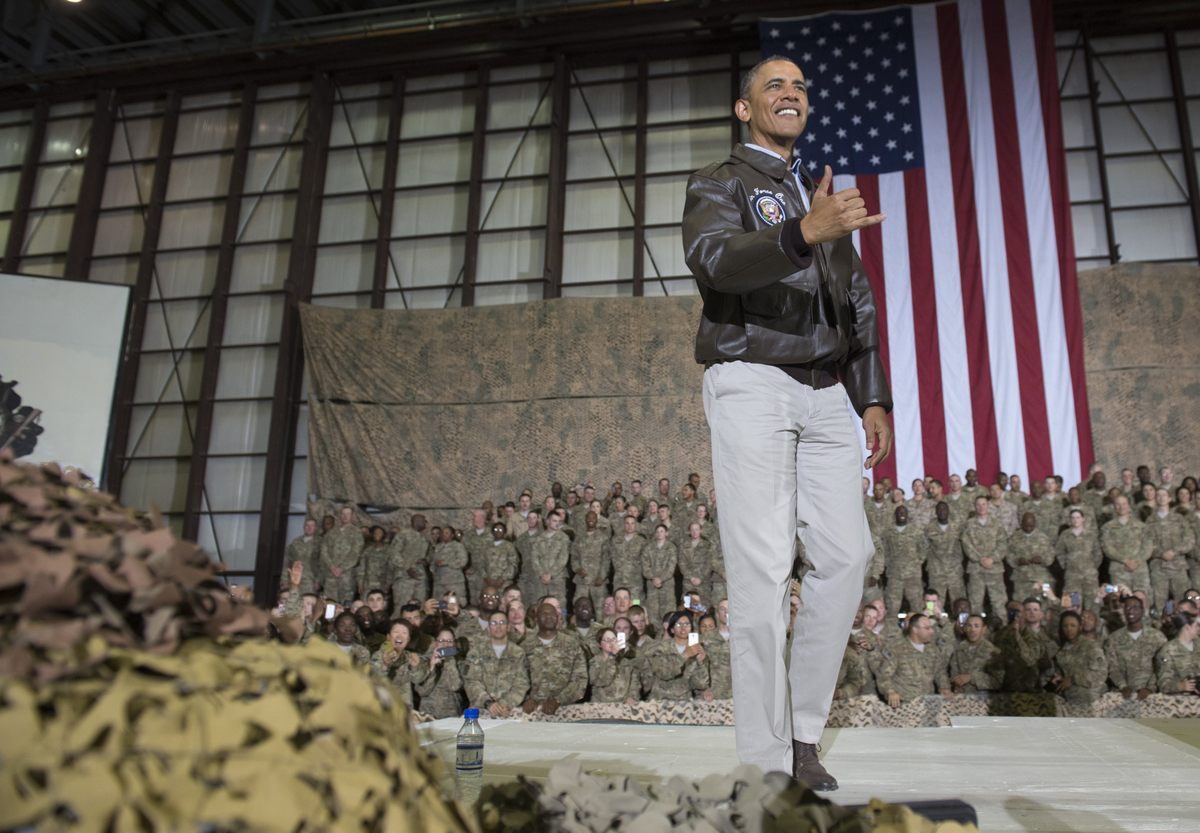

Go to any surfing beach today and you’d be hard-pressed not to find someone throwing a “shaka” hand—thumb and pinkie extended, three middle fingers curled against the palm. The iconic gesture, sometimes referred to as a “hang ten” or “hang loose,” has traveled far from its Hawai‘i origins. Today, American presidents, London nightclub goers, and even the emoji keyboard all sport the shaka hand.

Saa Tamba, owner of Tamba Surf Company on Kaua‘i, has been throwing shakas his whole life. “It’s just, from my perspective, a way of saying hi, a way of saying goodbye, and spreading some good spirit, you know, the eternal spirit of aloha,” he says. Tamba is quick to clarify that the shaka isn’t a wave. “You’re kind of like throwing it out there, you know, to your friend or someone away in the distance. So they’re kind of like catching the shaka,” he says. Tamba throws different shakas for different reasons. There’s the casual, one-handed shaka and there’s the “strong,” double-handed shaka for flagging someone down at a crowded concert, or saying hello to a friend you haven’t seen in a while.

The shaka hand grew in popularity across Hawai‘i in the mid-20th century thanks in part to used car salesman David “Lippy” Espinda, who was the first to link the gesture to the word—which is not actually Hawaiian in origin, but more likely Japanese. As a sign-off for his 1960s television ads, Espinda would throw a shaka and then say his catchphrase: “shaka, brah!” In the 1970s and 1980s, the gesture also featured prominently in reelection campaign ads for Frank Fasi, Honolulu’s longest-serving mayor. While Fasi and Espinda helped make the shaka hand more recognizable in Hawai‘i, surfing’s surge in popularity in the 1950s and 1960s helped export the gesture abroad. As Tamba puts it, “surfing spread it more than anything else.”

But the origins of where the shaka hand came from are far murkier than its global rise to emoji-keyboard stardom. One of several versions of the story suggests the gesture originated with early Spanish explorers asking for a drink. Another claims it came from mid-19th-century Chinese immigrants using the gesture to signify the number six.

However, according to the Honolulu Star-Bulletin, the prevailing origin story goes back about a century to Hawaiian plantation worker Hamana Kalili. His job was to feed sugar cane stalks into the rollers of a machine that would squeeze out the cane’s sweet juice. One day, Kalili’s hand got caught in the rollers and he ended up losing his three middle fingers. The company, the Kahuku Sugar Mill, gave him a new job as a security guard; every time he waved, he’d make what’s now known as the shaka hand. From there, local children mimicked and spread the gesture.

Accidents like Kalili’s certainly happened on Hawaiian plantations, perhaps even fairly often. “You know, there must be dozens of people with three fingers missing in the middle of the hand,” says historian Mike Mauricio of the Hawai‘i Plantation Village. While we know Kalili actually existed, Mauricio is unconvinced there’s enough evidence that he specifically originated the gesture.

University of Lisbon’s Cristiana Bastos, principal investigator of the Colour of Labour: the Racialized Lives of Migrants, agrees that Kalili’s role in originating the gesture is uncertain—but says the story is about more than one individual. While the story is “mythic,” she says, Kalili’s tragic tale serves as a reminder of a time “where plantations were very important” in Hawai‘i. The role of Indigenous Hawaiians in plantation history is often overlooked, Bastos adds. Ironically, the modern, feel-good shaka gesture is, in some ways, one of the echoes of that little-known, often brutal chapter of Hawaiian history.

When Hawai‘i’s plantations got going in the late 1800s, countless workers endured terrible conditions to grow and harvest “white gold,” or sugar cane, a “very sharp, unforgiving plant,” says Nicholas B. Miller, assistant professor at Florida’s Flagler College and a former researcher at the Colour of Labour project. The grim day-to-day working conditions only degraded further when harvest approached. Sugar cane fields would be set on fire to burn away the plants’ leaves, exposing the sugar-bearing stalk for easier collection. During these mass burns, Miller says, the fields “would look like the pits of hell were opening up.”

Kalili’s work at the plantation, both before and after his accident, which occurred around 1917, reveals one aspect of plantation history that’s often overlooked: the role of Indigenous Hawaiians as laborers well into the 20th century. “What’s really interesting about [the Kalili] legend is that it implies that a native Hawaiian was involved in the sugar economy well after native Hawaiians are not really seen as part of that world,” Miller says. Instead, historians often focus on the migrant contract workers coming to Hawai‘i, “sometimes not mentioning that there were Indigenous Hawaiians, too,” says Bastos.

In the opening decades of the 20th century, thanks to an influx of immigrants, plantation laborers became a far more diverse population. Chinese, Japanese, Portuguese, Norwegians, Koreans, Filipinos, Russians, and Puerto Ricans all came to find work in the sugar economy. As the islands’ population expanded in both size and diversity, Miller says the society was split into haole people—white outsiders who ran the plantations—and “locals,” which essentially encompassed everyone else. With foreign-born plantation workers considered as “local” as Hawaiians, the centuries-long history of the islands’ Indigenous community became increasingly overlooked, just one more ingredient in what has been popularly presented as a harmonious melting pot of diversity.

“If you look from the perspective of Indigenous Hawaiians who were dispossessed and who were not called in that celebration [of diversity] in equal terms, or in the terms that they would want for themselves because they were there beforehand,” says Bastos, “then you don’t get to see this as harmoniously.”

Whether or not Kalili was the originator of the shaka gesture ultimately doesn’t matter. Even apocryphal stories can reveal important truths about who we are, and remind us of forgotten histories. His tragic accident shows us that Indigenous Hawaiians had a greater presence in the islands’ plantation history than is often acknowledged.

So the next time you see a surfer—or an American president—throw a shaka, remember there is some deep history behind what Tamba, like most people, think of as “just a good way of spreading good vibes.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook