Head Space: Behind 10,000 Years of Artificial Cranial Modification

Deliberate modification of the skull, also called the “Toulouse deformity.” (Photo: Didier Descouens/WikiCommons CC BY-SA 3.0)

In 2013, archaeologists working in Alsace, in eastern France, uncovered something incongruous, and to the untrained eye, very strange. The researchers discovered the tomb and skull of an aristocrat, who died some 1,600 years ago. Her skull was heavily deformed, with the front flattened, and the rear rising into a cone shape. An amateur digger might have been forgiven for thinking they had found one of the “Grey aliens” that UFO-spotters regularly claim to see.

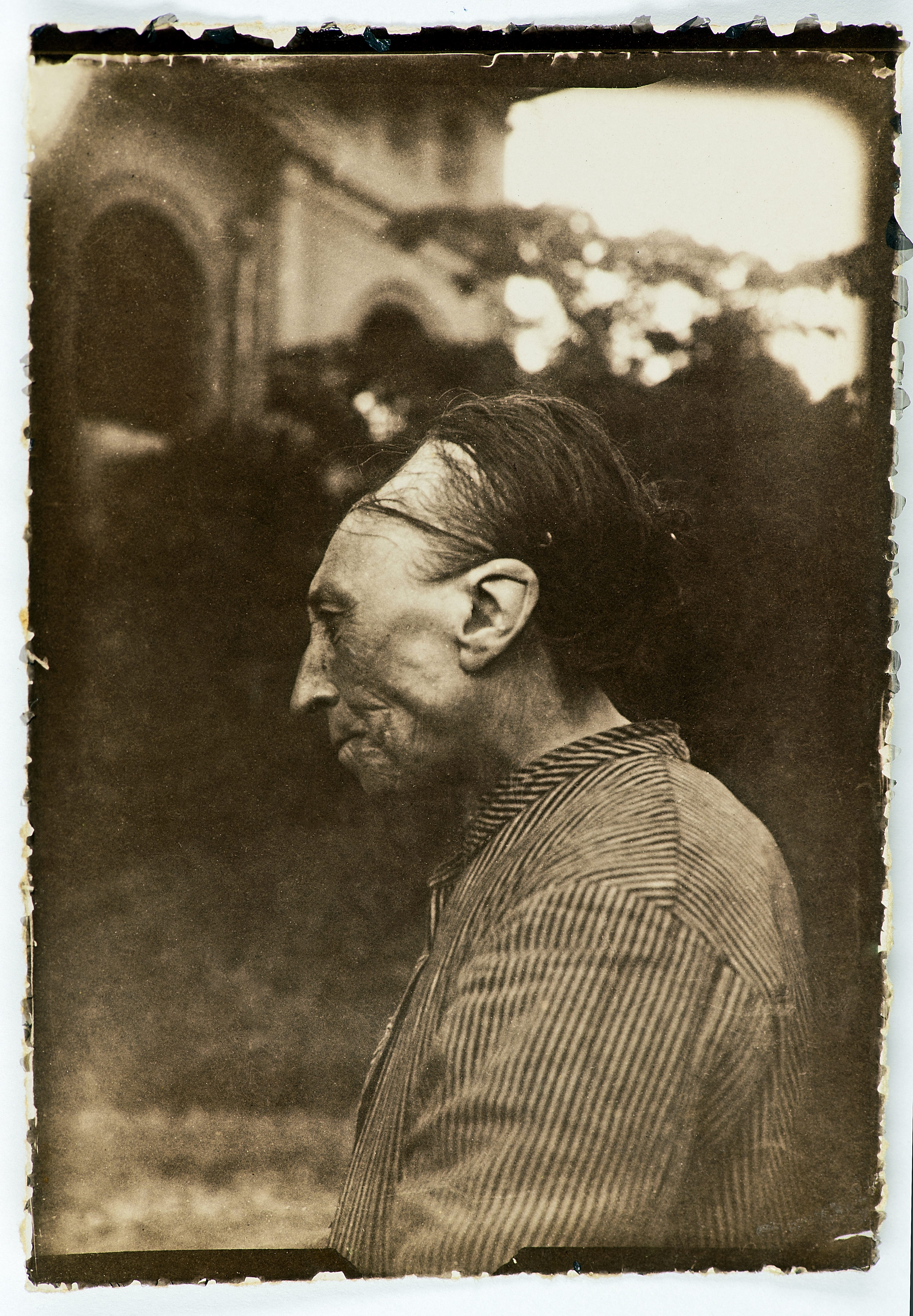

This was an example of “artificial cranial deformation,” or in layman’s terms, the practice of altering the head’s natural shape through force. As odd as it seems, this was not a singular incident, or only representative of fifth-century practices, or something that only happened in France. Until the early 1900s, a form of artificial cranial deformation was still taking place in Western France, in Deux-Sevres. Known as the Toulouse deformity, the practice of bandeau was common amongst the French peasantry. A baby’s head would be tightly bound and padded, to protect it from accidental impacts. At around the same time, the practice was still occurring in Russia and the Caucasus, as well as in Scandinavia.

It turns out that altering the shape of one’s head is not shockingly unique; it’s incredibly common, across time and geography. Its meaning isn’t fixed, so understanding why and how it happens can reveal much about the societies who choose to change the shape of their heads.

Originally, head flattening was instituted to “distinguish certain groups of people from others and to indicate the social status of individuals.” In Europe the practice was most popular with tribes that emigrated from the Caucasus region of Central Asia, like the Huns, Sarmatians, Avars, and the Alans. Indeed, that region is where the remains of the earliest suspected practitioners of artificial cranial deformation were discovered.

While early European observers of the practice in France and in Eastern Europe reportedly pitied children whose heads had been bound, subsequent research has led experts to believe that cranial modification has no impact on cognitive function, nor is there a difference in cranial capacity. According to a 2007 paper in the journal Neurosurgery, “there does not seem to be any evidence of negative effect on the societies that have practiced even very severe forms of intentional cranial deformation.”

(Photo: Didier Descouens/WikiCommons CC SA 3.0)

(Photo: Didier Descouens/WikiCommons CC SA 3.0)

In Iraqi Kurdistan, near the borders with Iran and Turkey, a cemetery from the proto-Neolithic period was discovered in 1960. The site, called Shanidar Cave, dates back more than ten thousand years, and contains the bodies of 35 individuals, including some of the first examples of intentional skull shaping. The Huns and Alans both seem to have originated in Central Asia, and as they pushed westward into the Roman Empire (often invited as mercenaries), their practice of head binding came with them, and was adopted by some peoples living in Western and Central Europe.

The earliest written reference we have of artificial cranial deformation comes from Hesiod, a Greek poet who lived between 750 and 650 B.C. In his book of mythology, The Catalogues of Women, Hesiod referred to a tribe from either Africa or India called the “Makrokephaloi” (or “Macrocephali”), which roughly translates to “the big heads.”

Hippocrates, the father of Western medicine, also mentions the Macrocephali in his work, On Airs, Waters, and Places, which was written around 400 B.C. Not only did Hippocrates mention the Macrocephali, but he got their techniques right. Rather than making the people mythological, Hippocrates tells us their methods, and their reasons: “They think those the most noble who have the longest heads … after the child is born, and while its head is still tender, they fashion it with their hands, and constrain it to assume a lengthened shape by applying bandages and other suitable contrivances …”

And it is not only European authors who found the practice amazing. Xuanzang, a Chinese Buddhist monk and traveller, whose 17-year journey to India inspired the Chinese classical novel Journey to the West, reported on the form of the practice he came across in modern-day Xinjiang, in Western China. Xuanzang speaks of the people of Kashgar, where “children born of common parents have their heads flattened by the pressure of wooden boards …”

(Photo: Tropenmuseum/ Royal Tropical Institute/WikiCommons CC BY-SA 3.0)

Thus, this woman discovered in France fits into a broader cultural narrative—one of migration, of high rank and social status, and of conquest. While it would be easy to write the practice off as being an odd thing that was popular thousands of years ago, it wouldn’t be anywhere near the truth.

Across the Americas, in various tribes, infants had their heads bound and shaped by their parents. Both the Mayans and the Inca shaped their children’s skulls, as did the Choctaw and the Chinookan tribes in what is now the United States. Their reasons must have been the same, to allow for the child to fit into the fabric of their societies, and to signify class. For the Maya, it also held a religious significance.

According to Gonzalo Fernandez de Oviedo, a Spanish chronicler of the conquest of the Americas, a Mayan explained: “This is done because our ancestors were told by the gods that if our heads were thus formed we should appear noble …”

Two different styles of artificial cranial deformation were prevalent in Mayan culture, and indicated the wearer’s rank. Those who were destined (or hoped) to hold some position of high status, were given what is referred to as “oblique deformations,” which resulted in a high, pointed head shape. However, the general populace could only use an “erect deformation,” which led to a rounded skull shape, with flattening on the sides. Whether these shapes were in imitation of a jaguar’s skull, to show prowess, or in the shape of the maize god, to symbolise fertility, is a matter of debate among historians and archaeologists.

Paracas skulls on display at Museo Regional de Ica in the city of Ica in Peru (Photo: Martin Tlustochowicz/Wiki Commons CC BY 2.0)

Paracas skulls on display at Museo Regional de Ica in the city of Ica in Peru (Photo: Martin Tlustochowicz/Wiki Commons CC BY 2.0)

Artificial cranial deformation was also recorded amongst the remains of people as far distant as Australia and the Caribbean islands. But it’s not just an ancient practice. It still occurs in some of the world’s more remote outposts.

In Polynesia, the tradition still (rarely) occurs, as it does in the people of Mangbetu tribe, of Congo. In Vanuatu, the shape is associated with famous folk heroes and religion. A person from Malekula, an island in the Vanuatu chain, told the veteran anthropologist Kirk Huffman: “it originates with the basic spiritual beliefs of our people. We see that those with elongated heads are more handsome or beautiful, and such long heads also indicate wisdom.”

More than a millennium after she died, the ancient aristocratic woman discovered in Alsace isn’t alone. Like any body modification, beauty is in the eye of the beholder. She still has people whose cultures revere the same head-shape and customs as her own.

(Photo: Wellcome Images, London)

(Photo: Wellcome Images, London)

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook