The Hidden History of the First Black Women to Serve in the U.S. Navy

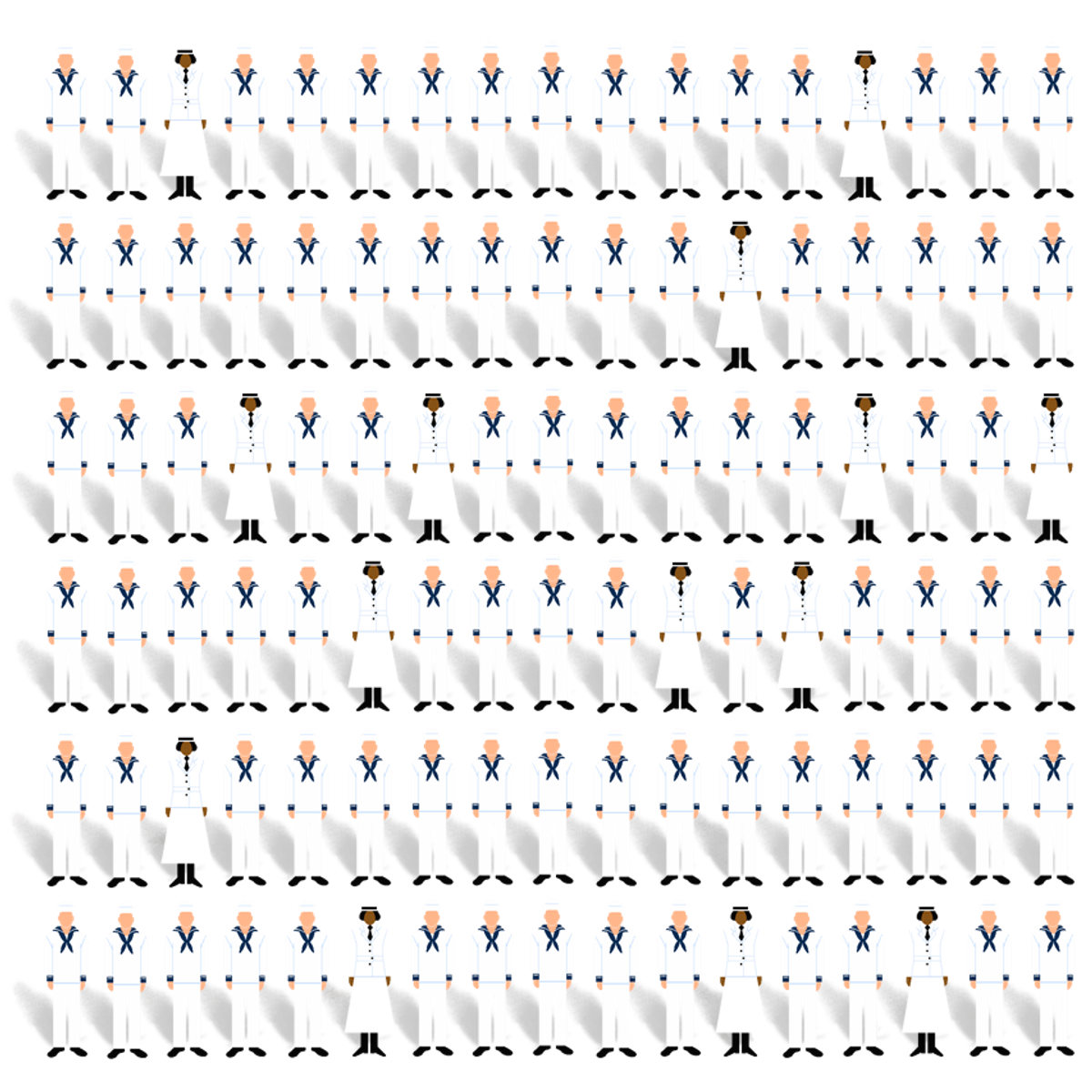

The Golden Fourteen were largely forgotten—but a few veterans and descendants could change that.

When Jerri Bell first wrote about the Golden Fourteen, their story only took up a sentence. These 14 Black women were the first to serve in the U.S. Navy, and Bell, a former naval officer and historian with the Veteran’s Writing Project, included them in a book about women’s contributions in every American war, co-written with a former Marine. But even after the book was published, Bell couldn’t get their story out of her head.

“It made me kind of mad,” Bell says. “Here are these women, and they were the first! But I think there was also a general attitude at the time that the accomplishments of women were not a big deal. Women were not going to brag.”

Bell was one of a few researchers who have been able to track down documents that acknowledge the lives and work of these Black women. She knew that during World War I, the Fourteen had somehow found employment in the muster roll unit of the U.S. Navy in Washington, D.C., under officer John T. Risher. One was Risher’s sister-in-law and distant cousin, Armelda Hattie Greene.

The Golden Fourteen worked as yeomen and were tasked with handling administrative and clerical work. They had access to official military records, including the work assignments and locations of sailors. At the time, Black men who enlisted in the Navy could only work as messmen, stewards, or in the engine room, shoveling coal into the furnace. They performed menial labor and weren’t given opportunities to rise in rank.

Bell wasn’t surprised to learn about the barriers faced by service members of color. She knew that Josephus Daniels, the Secretary of the Navy at the time, was a documented white supremacist with ties to the Wilmington Massacre, in which a white mob overthrew a local Reconstruction-era government and murdered Black residents. During the First World War, the U.S. Navy maintained the status quo of racism that continued long after. Many Black service members were also targeted by white mobs after the war.

What was surprising was that a legal technicality had paved the way for Black women to work for the Navy more than a century ago. A shortage of clerical workers led then-president Woodrow Wilson to pass the Naval Reserve Act of 1916, which asked for “all persons who may be capable of performing special useful services for coastal defense.” The Golden Fourteen were part of a larger group of over 11,000 women, almost all of them white, who were able to join the navy as yeomanettes, the title given to female yeomen.

Of the few archival records that exist of the Golden Fourteen, one thing is clear: In a period when stepping out of line could have violent repercussions for Black women, they worked without drawing attention to themselves.

“This is quite a novel experiment,” wrote the sociologist Kelly Miller in The History of the World War for Human Rights, published in 1919. “As it is the first time in the history of the navy of the United States that colored women have been employed in any clerical capacity … It was reserved to young colored women to invade successfully the yeoman branch, hereby establishing a precedent.”

Bell’s fascination with the Golden Fourteen only deepened. She is now writing a book about them, and has spent more than four and a half years, as well as thousands of dollars, collecting archival materials. She’s waited patiently to get military and civilian personnel records from the National Archives, which can often take years, and has combed through historical accounts that have not been digitized. She’s looked at photos and spoken with the last living descendant of the Risher family, who says that his aunt, Greene, never spoke of her naval service.

The memory keepers who tell the story of the Golden Fourteen are almost all veterans. Researchers like Bell have the personal connection and the professional knowledge to recover what fragments remain. She feels a powerful responsibility, to the point that she missed the first deadline for her manuscript nine months ago. Because she is telling a story that has been so thoroughly forgotten—and arguably erased—she wants her research to be truly comprehensive. “I just discovered some documents that I need to physically go to another state to get access to,” Bell says. “I couldn’t turn in the manuscript before. I know I owe these women more than that.”

There is one other place where stories of the Golden Fourteen have been passed down: in family histories. When Tracey L. Brown was 10 years old, she looked through her family photo album and saw a light-skinned woman she didn’t recognize. Her grandmother, Nan, told her that the woman with the blonde hair and hazel eyes was Brown’s great-grandmother, Ruth Ann Welborn. Welborn was one of the Golden Fourteen. Though she seemed to pass as white, she, like Brown, was African-American.

“I had known that she was one of very few Black women there,” Brown says. “But I didn’t know that there had been 14—I wasn’t expecting that many. I remember hearing about that, as a child, that there was some sort of scheme in how they were even able to enlist. I know it wasn’t simple.”

Although Brown grew up understanding who her great-grandmother had been, she didn’t grasp the magnitude of what Welborn and the other women had done until she was much older. Now a practicing attorney in a New York law firm, Brown started to dig deeper after her father, Ronald H. Brown, who had served as Secretary of Commerce under President Bill Clinton, died in 1996. In her grief, she decided to write a memoir about him. “It was sort of the perfect storm,” Brown says. “I had just lost him, so I was really committed to telling his story.”

Brown talked to friends, family, and even President Clinton himself. After interviews with her grandmother, she finally began to unearth more about Ruth Welborn. “It was so exciting to even begin pursuing these stories,” Brown says. “There have been so many stories that have been lost in our community, and it was nice to be able to have a little slice.”

Ruth was the daughter of Walter Welborn, the son of a white merchant, Johnson W. Welborn, and a woman he enslaved at his house in Clinton, Mississippi, whose name and date of birth remain unknown. In 1863, during the chaos of conscription riots that followed the Emancipation Proclamation, Walter and his brother Eugene escaped from the biological father who had enslaved them. According to Brown’s memoir, their mother dressed them in Confederate uniforms, and perhaps thanks to the fair skin they had inherited, they were able to escape onto a train to Washington.

In Washington, Walter Welborn was a free man, and he married Elexine Beckley, who came from a well-educated and affluent Black family. Their five daughters inherited Walter’s fair skin, blonde hair, and hazel eyes. Like their mother, the five daughters graduated from the best schools available to Black children at the time.

In 1918, after graduating from Dunbar High School, Ruth decided to join the Naval Reserve, becoming one of the Golden Fourteen. “Ruth seemed very stern,” Brown says. “She was a stoic person: In every picture, her posture is perfect. She looks very commanding, and I can’t imagine playing with her like I had with my great-grandmother on my mother’s side.” She and Brown’s father were both buried at Arlington National Cemetery.

Although Brown is one of the few to write about the Golden Fourteen, she is not alone. The Washington Post columnist Courtland Milloy wrote about Sara Davis Taylor, another yeomanette, in 1992. Taylor reportedly tried to join the Navy even before 1917. She and other Black women were turned away by military doctors, Milloy writes, because “they all allegedly had flat feet.” Only after President Wilson’s 1916 law were they assigned to Risher’s muster roll unit.

Relatively few of these stories have been passed on. Brown’s memoir is now out of print, and, according to Milloy’s column, Taylor and her husband did not have children. Richard E. Miller, a naval veteran and historian, laments in an article that many details may remain a mystery. “It is believed that all of the Black Navy women from the First World War have now passed away,” Miller writes. “Regrettably, the ‘golden’ place they deserved as pioneers in the annals of Afro-American, as well as naval and women’s history, was never accorded them during their lifetimes; except perhaps within their immediate family circles.”

No one is quite sure how the Golden Fourteen convinced a segregated military to hire them, years before women could vote and half a century before the end of Jim Crow. Some historians theorize that all 14 worked in the same office, where white supervisors could monitor and protect them. Others suggest that most of the Golden Fourteen had light enough complexions to pass for white—though photographs suggest that this was not the case for all of them.

These questions have bothered Regina Akers, a historian with the Naval History and Heritage Command, for years. Akers, who is Black, has made a name for herself by centering Black women in military history. “To learn of these women was exciting, and also frustrating,” Akers says. “There are some sources out there that mention them, but it’s always done in such a tangential way.”

The historical backdrop makes the achievements of the Golden Fourteen all the more surprising. “Lynchings were a popular occurrence; they were carried out with little threat of reprisal,” Akers says. “ If a black person approached a white person, they either moved aside, or they understood that you didn’t look them in the face, and just called them ma’am or sir.”

The U.S. military remains a site of systemic racism. This summer, the Chief of Staff of the Air Force released a video describing the racism he’s experienced during his career. When the Military Times surveyed hundreds of its readers in 2018, more than half of respondents of color said that they had witnessed white nationalism or racism from their peers.

Such stories have led Bell, who is white, to reflect on her own career as a naval officer. “I would ask Black colleagues, some working under me, about their experience as Black sailors in the Navy,” she says. “I realize that whatever my intentions may have been, they did not trust me to tell me what was really going on. People say that once you’re in uniform, no one looks at the color of your skin—but that’s crap.”

For Akers, the Golden Fourteen are compelling not because they are unique, but because they shared the struggles of so many Black Americans who have fought for equality. “I think it’s important to remember that the efforts to bring about equal opportunity are part of the larger civil rights movement of that time period,” Akers says. “There has always been a civil rights movement in the U.S., because there have always been people advocating for change and fighting for their rights.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook