This Vast Photo Archive Is Hidden Inside a Cold, Heavily Guarded Limestone Mine

Over 11 million Getty images are on ice near Pittsburgh.

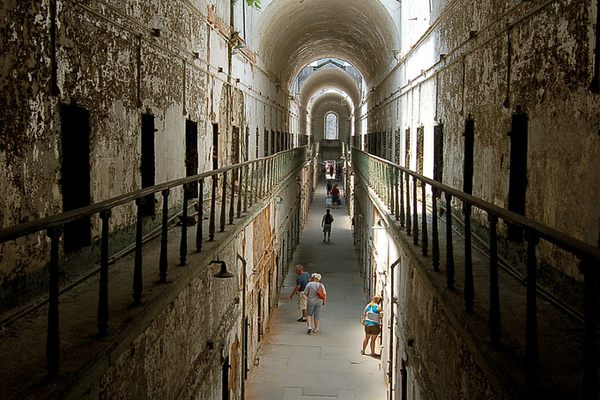

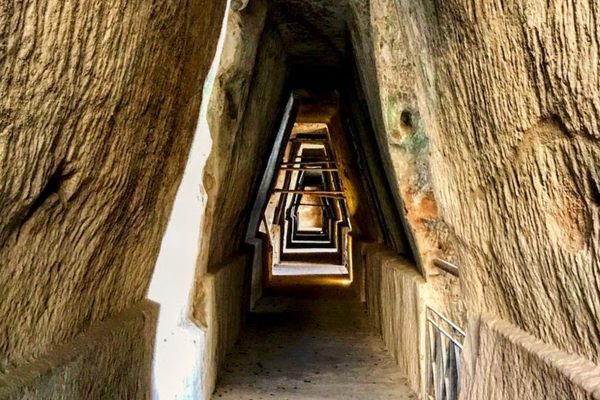

To get into the Bettmann Archive, about 90 minutes north of Pittsburgh, you need more than a library card. You need the proper credentials to get past the armed guards at the door. You need to be gloved and swaddled in several layers to deal with the cold. And you need to be OK with claustrophobic conditions, since the trip requires being shuttled hundreds of feet underground.

If you meet all those conditions, you might get a glimpse of Getty Images’ hidden trove of photographic history.

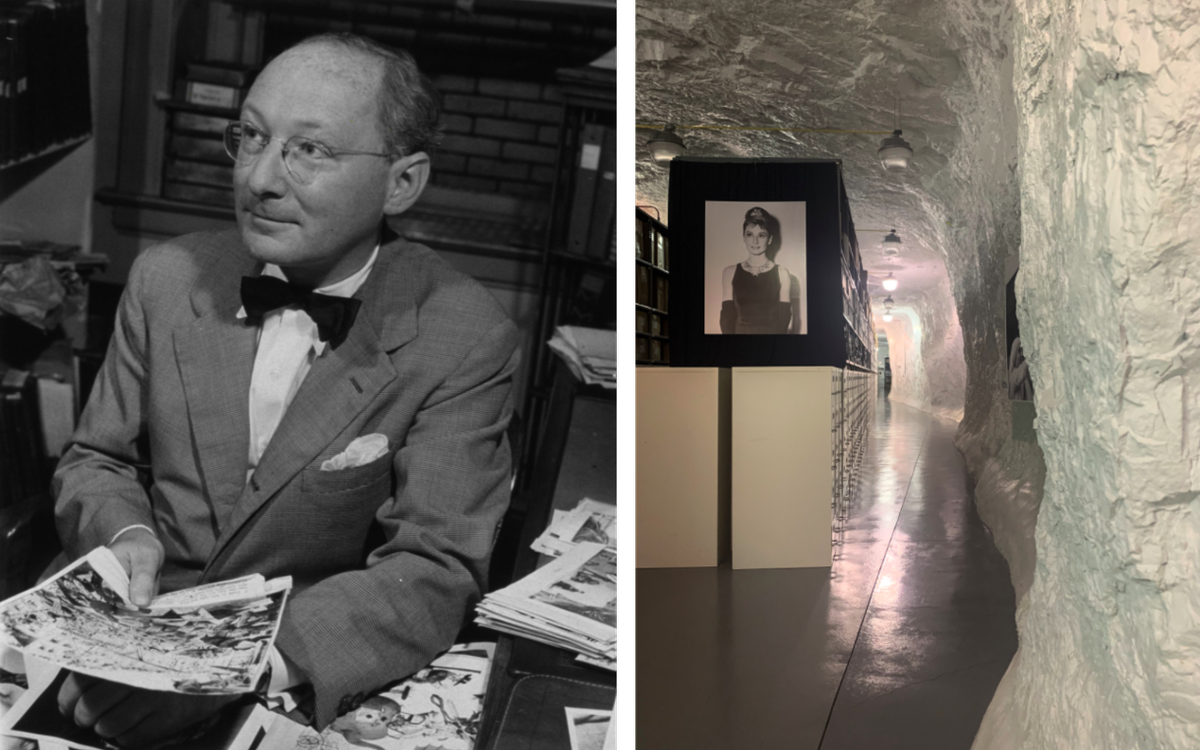

Eighty-five years ago, 32-year-old Otto Bettmann arrived in New York with two heavy steamer trunks. Bettmann had hustled out of his home country, Germany, after being fired from his job as a rare book curator—his crime: being Jewish—on the eve of Hitler’s rise to power. (It wasn’t long after Bettmann’s departure that the Third Reich decided that books, too, had to go.)

The steamer trunks Bettmann hauled across the ocean weren’t loaded with clothes; Bettmann had left all of his behind, save for the ones he wore. They weren’t loaded with money either; that had been seized by the Nazis as Bettmann skipped the country (part of the so-called Reich Tax that removed assets from Germans, especially German-Jews, for leaving).

What those trunks were crammed with was photographs and negatives—the humble beginnings of what would become, by the end of the century, one of the world’s largest collections of iconic photography.

The suitcase contents, according to a New Yorker article in 1939, could be traced back to Bettmann’s fascination with books. The young curator—and accredited historian, thanks to his 1927 doctorate in history—had trekked across Europe, taking photographs with his Leica of book illustrations and other literary materials in libraries and museums.

Having written his university dissertation on literary piracy and copyright issues, Bettmann knew early on that he would do more than just collect images. He would curate and catalog them too, as he had done with books in Germany, and license them to the clamoring clients of a newly booming media industry. Magazines like LIFE, Look, and Time were beginning to take their popular place in American life, and Bettmann was there to cater to their needs. After he arrived in the U.S., he expanded his collection by posting advertisements seeking photographs in some of the very magazines to which he would later license images.

“His business grew over the years; he became known as ‘the Picture Man,’” says Bob Ahern, the director of archival photography at Getty. “At that time, there was a massive explosion in photographs and magazines. There was a massive appetite to see the world, and Bettmann took advantage of that.”

Wherever things were happening, Bettmann (or an employee of an affiliated photo agency) was there. War zones. Rock concerts. Economic upswings and downturns. When Truman defiantly held up a Chicago Daily Tribune declaring Dewey the victor of the 1948 presidential election, it was a Bettmann photograph that memorialized the historic gaffe.

So ubiquitous was the Bettmann name in print media that when a dinner partner of the unassuming German learned his name, she exclaimed, “I thought you’d died 300 years ago,” according to a laudatory New York Times profile. He was “[p]art scholar and part Barnum”—a doctor by degree and a showman by trade.

Over the decades that followed the collection grew, swollen with images of practically every event worth writing on a calendar. When Bill Gates bought the Bettmann collection—in 1995, three years before its namesake’s death— Bettmann declared that Gates “now owns the history of everything.”

But by 2001 the collection could no longer remain in New York. With fluctuating temperatures in a city with four distinct seasons (including hot, humid summers), “the conditions were pretty terrible,” Ahern says. “They had to place this collection somewhere where it’d be preserved, and that place is one-and-a-half hours out of Pittsburgh, 220 feet down a limestone mine.”

When Gates moved the collection into the mine, he simultaneously erected a digital paywall, thereby securing the collection across both physical and digital space.

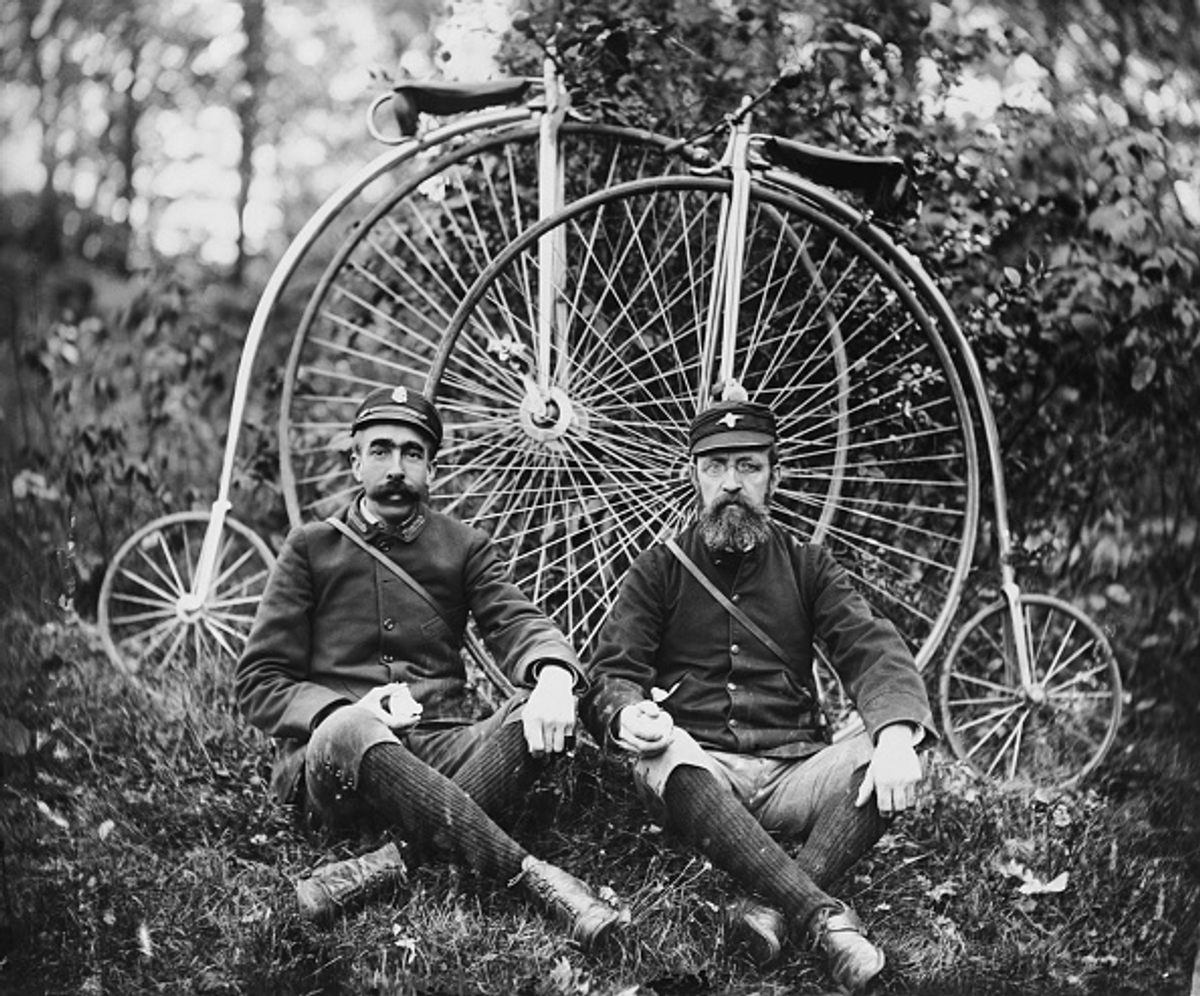

Sold in 2016 to Visual China, which immediately gave photo licensing rights to Getty, the Bettmann collection has remained in its subterranean home-cum-fortress, to keep the trove of images—some of which date back to the inception of photography itself—from disintegrating.

The 11-million-image Bettmann collection is a small piece of Getty’s 100-million-image photographic empire, but it’s the only one secreted below the surface of the Earth, protected by armed guards. The limestone mine is part of a facility known as Iron Mountain, which once supplied Pittsburgh’s steel mills. Today Getty shares its labyrinthic passageways and cool, dry environment with other collections—including confidential government and private records—in a space that protects and preserve Bettmann’s photographic legacy.

The Bettmann Archive is maintained day to day by Leslie Stauffer and Sarah Kubiak, archivists who call themselves the “Queens of the Bettmann”—an apt nickname given the 10,000-square-foot facility they oversee.

“There is a 5,000-square-foot space consisting of what we call ‘classic library finding aids,’ such as card catalogs and microfilm readers, as well as modern archival technology, including scanning equipment and state-of-the-art software,” says Stauffer. “We also have a 5,000-square-foot cold-storage archive containing all of the multimedia content.”

The trove is equal parts secret library and semi-natural refrigerator. The mine’s temperature is typically a little lower than that of the outside world, but far more constant. There’s also a separate, fully refrigerated section within its halls—the section that houses the most delicate materials, which can’t handle any temperature deviations.

“Since we maintain the temperature inside the cold-storage archive at a constant 37 degrees [Fahrenheit], we often wear hats, coats, and gloves year-round,” says Kubiak. “While the cold temperature can be physically challenging for us as archivists, it is of the utmost importance to preserve the visual history of the late 19th and 20th centuries.”

Bettmann’s archive is large enough that not all of the images are in the cloud; some reside exclusively in the Pennsylvania mine, waiting for the moment when a client pulls them from the underground repository of history. Ahern says that much of the archive’s contents has never been published.

Whether Bettmann could have foreseen the burial of his life’s work is hard to say. Yet even hidden away, his archive remains one of the most utilized image libraries in the world. It’s probably safe to say, however, that most people looking at one of his pictures would never know that it was pulled from underneath the ground in the Pennsylvania countryside.

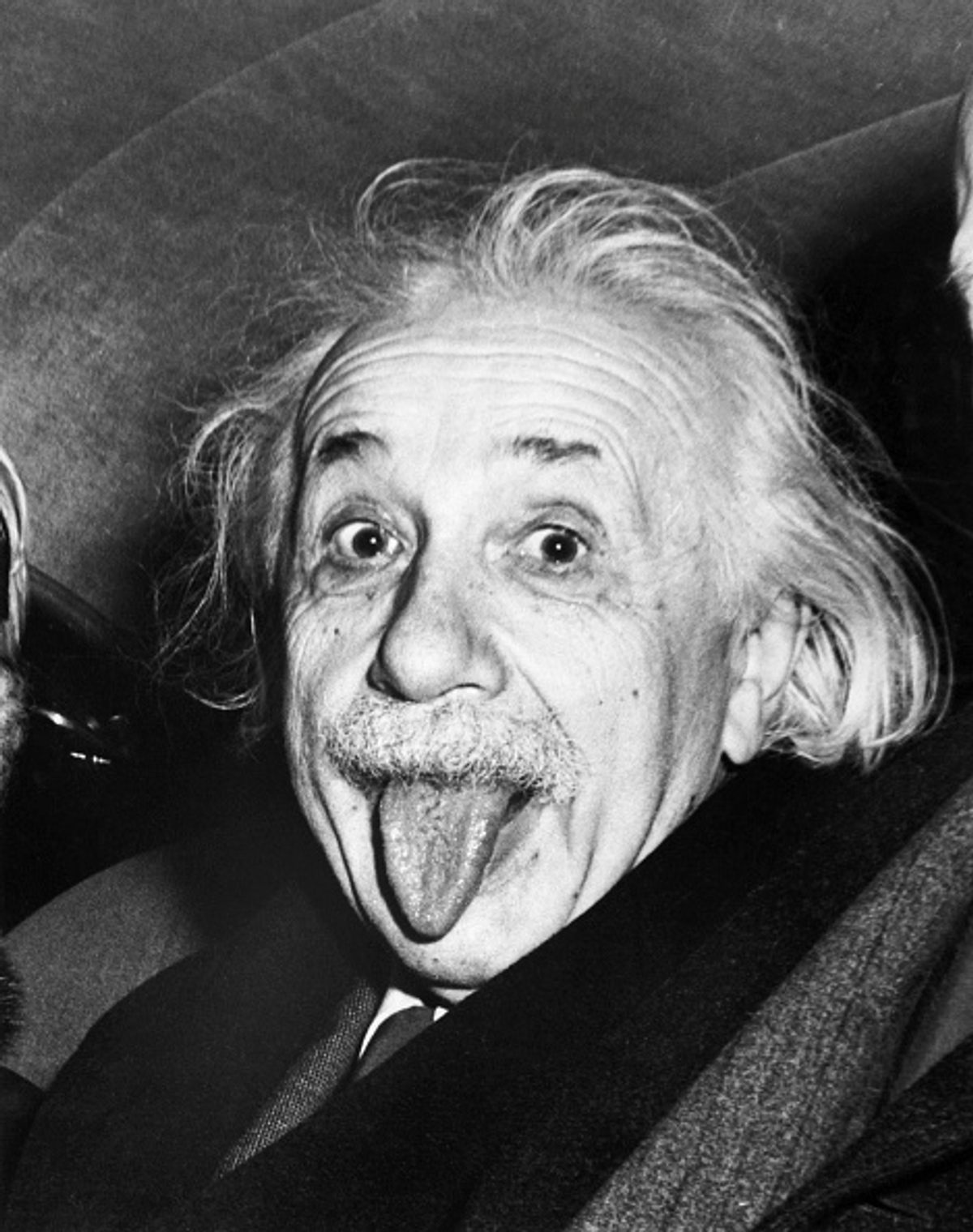

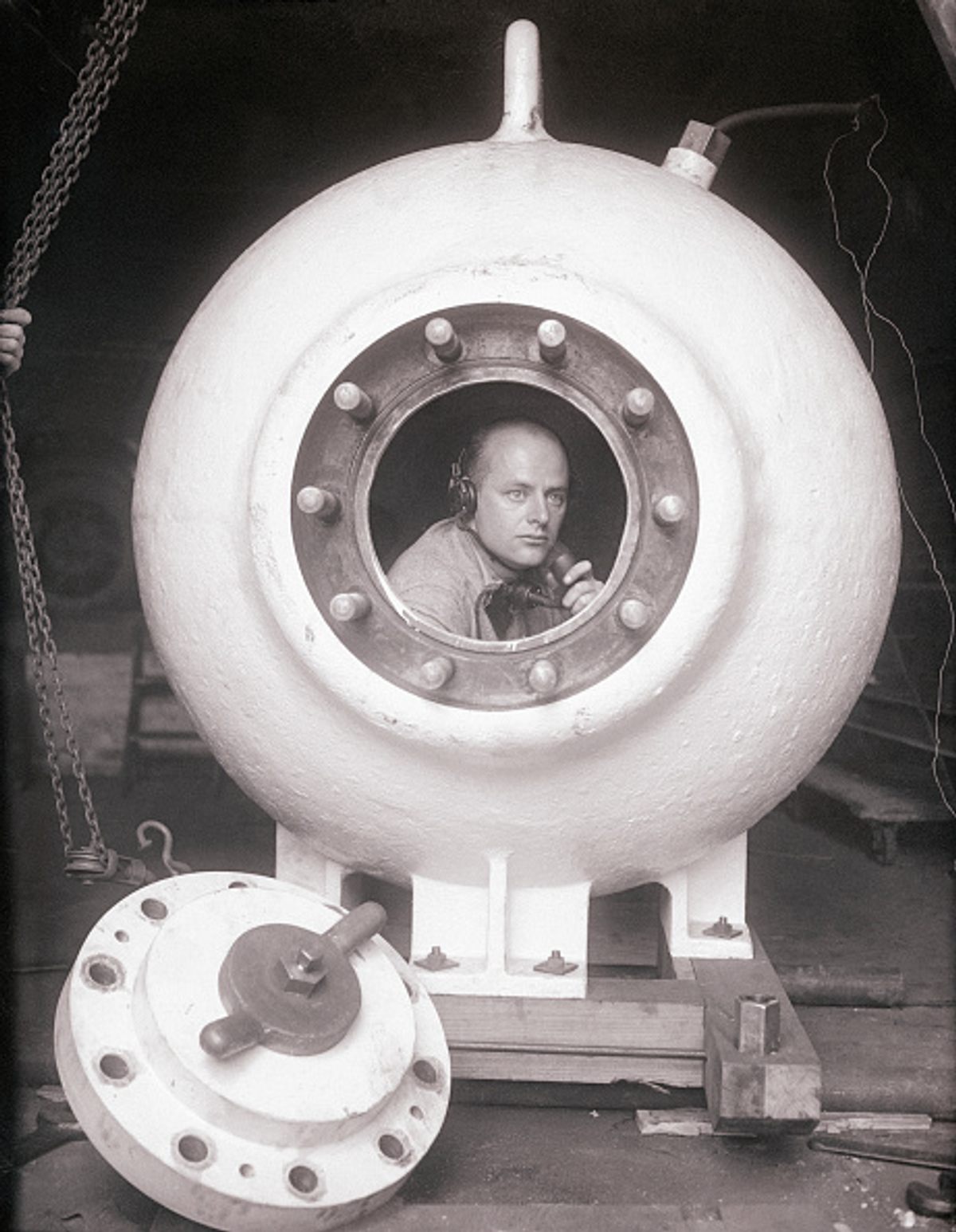

Below are a few choice examples of the diverse and voluminous photographic portfolio Bettmann collected in the decades he spent building the collection.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook