Sometimes Trash Is Treasured in America’s National Parks

Bottles, cans, and more can reveal a long history of industry, recreation, and shenanigans.

Around 14 years ago, when Jordan Raphael was, as he puts it, “a naive young biologist,” he was newly stationed at Fire Island National Seashore, where he is still on staff. The park sits on a barrier island off the coast of Long Island, New York, roughly 60 miles from Manhattan. It’s famous for its white-quartz ocean shoreline, vibrant gay scene, and salt-pruned maritime American holly forest, cradled between sand dunes and a placid bay. For his research, Raphael wandered the woods, surveying the understory and trying to understand why the island’s white-tailed deer munched on some saplings and not others. When he reached an area just north of some of the dunes, a little ways off the boardwalk, Raphael kept stumbling across bits of trash—an aluminum can here, a glass baby food jar there—maybe 50 or 60 containers in total. “I remember thinking, ‘What the heck? Why is all this garbage out here?’” he says.

Raphael called his boss; he figured they ought to get rid of it. But he soon learned that the garbage had to stay. This particular trash had been deemed historic.

On the county, state, and national levels, wilderness parks are often beloved for their natural wonders: handsome trees, cantilevered rock formations, shrinking glaciers—and not the things that people leave behind in them. But over time, many park staffers have found themselves caretakers of this historic debris.

The older stuff strewn around can be a window into understanding a landscape and how people have used it. That’s how a couple dozen decades-old bottles and cans came to be cultural heritage objects in the custody of Fire Island staff.

You’d be forgiven for thinking that archaeologists’ greatest finds would be a sword or a skull or a ruined temple. Digs do occasionally turn these things up, but the real windfall for archaeologists has long been trash. And they wouldn’t have it any other way.

Archaeology isn’t about treasure—“It’s looking at people’s garbage,” Rebecca O’Sullivan, a public archaeologist with the Florida Public Archaeology Network (FPAN), said on a recent episode of “The Materialists,” the archaeology podcast she cohosts. “You could argue that trash is one of the things that make us human,” she added. “There’s truly nothing that archaeologists love more than garbage.”

Trash offers a picture of how people have lived—what they used, where they used it, what they valued, what they did with it when they were done. But not all of this old trash is equal in either what it can tell us or what the law considers it. While different types of public land in the United States—managed by the Bureau of Land Management or U.S. Forest Service, for instance—are subject to different laws about land use, there is overarching legislation about protecting things that are old, mundane or otherwise. Under the Archaeological Resources Protection Act of 1979 (ARPA), anything found on federal land, such as the Fire Island National Seashore, that is 100 years or older is considered an archaeological resource. The National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, which created the National Register of Historic Places, lowers the age threshold to 50 years but has other criteria, such as association with an important person or event.

To catch an archaeologist’s eye in the field, trash ideally helps tell a story. In the case of Fire Island, Raphael says, the bottles and cans show how people used the land in the decades just before it became a national seashore, in the 1960s. At the time, the surrounding communities were growing, but municipal services, such as trash collection, didn’t keep pace. The story goes that one community, when it accumulated enough debris, would schlep it over to the dunes and chuck it into the woods, Rapahel says.

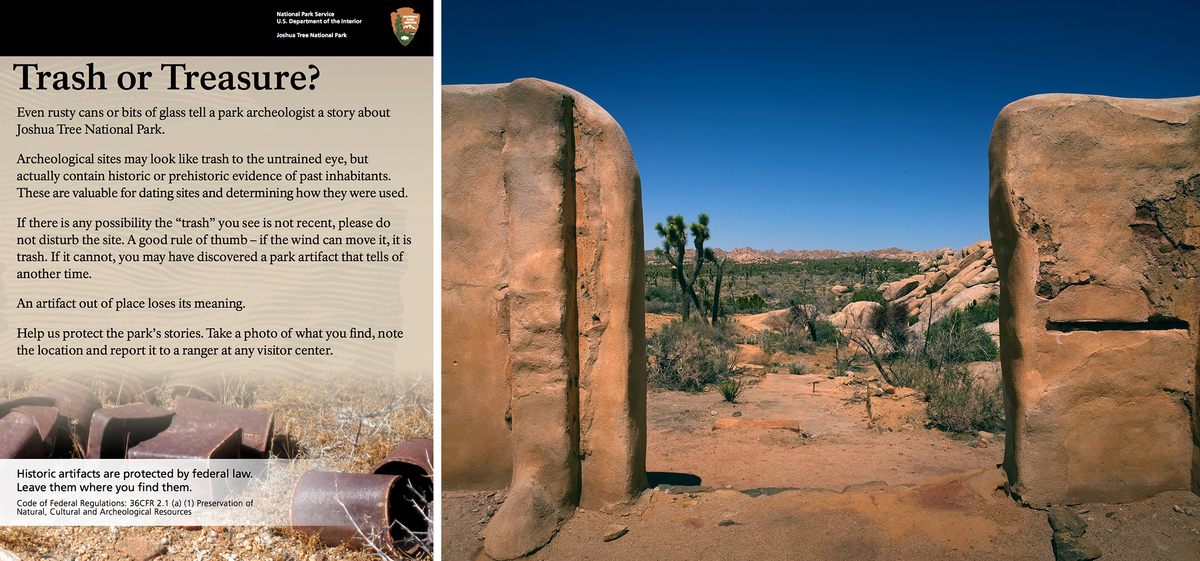

Joshua Tree National Park in California is strewn with yet more historic trash, which speaks to centuries of mining and recreation. The crumbling adobe ruins of Ryan Ranch—a 19th-century homestead—have attracted generations of vandals. The home and surrounding structures have obvious historic value, and were surrounded by scattered old detritus—nails, cans, and more. To the untrained eye it might have seemed like litter, but it was all part of the same history. “Unfortunately, most of the area has been pretty much picked clean, compared to what it used to be,” says Jason Theuer, the park’s cultural resource branch chief. There are still some historic cans and tools laying around, Theuer says, but “on the whole, most stuff has just walked away.” The ranch and Lost Horse Mine, several miles away, are linked as a historic district, telling a story about the prospectors who tried to put down roots in California’s desert.

An area on the park’s southern boundary holds more recent artifacts that speak to decades of camping and partying beneath the starry desert sky. According to Theuer, that’s especially true in a tract that was inside the park boundaries in the 1930s—when it was a national monument, but not yet a national park—but then spent a few decades under the Bureau of Land Management. Between the 1950s and 1970s, people gathered there and established informal campgrounds, Theuer says. It’s full of bottles, soda cans, cartridges, and more, much of which can be dated from makers’ marks, types of seams, and the openings on top. These relics of what Theuer calls “mid-century recreation archaeology” are sometimes found amid patinated glass or hammered nails from older periods, he says, suggesting that vacationers had some interest in collecting intriguing bits from older historic sites.

Historic trash has the most value when it’s left alone. Just like any other form of archaeology, context is key, and what’s around any given piece of trash is as or more important than the item itself. Archaeologists and other park staff often choose to leave the trash in place, but visitors, either through well-meaning ignorance or the desire for souvenirs, may not. Some guests just make off with stuff, while others with the “pack-it-in, pack-it-out” ethos might think they’re helping out. Joshua Tree made the news during the federal government shutdown in 2019, when some well-intentioned folks went in, garbage bags in hand, to clean up after some raucous, messy guests, Theuer says. Sometimes, he adds, they went too far, and picked up some historic stuff, too.

When historic trash is picked up by a visitor, Theuer’s staff tries to steer the person back to where it was found. It’s not always possible to do that, and there’s always the risk of putting it back in the wrong place. “When things just get dropped off and we don’t know where they came from, we don’t want to make a false record of the past,” Theuer says. “I don’t want to confuse the people who are sitting in my chair after me—I don’t need to make their life harder by making fake archaeological sites out there.” When Theuer’s crew can’t put historic trash back, they either add it to their collection (which is inaccessible to the public, but provides material for visitors’ center displays) or add it to traveling trunks that educators use to teach students about the history of the park and archaeological methods.

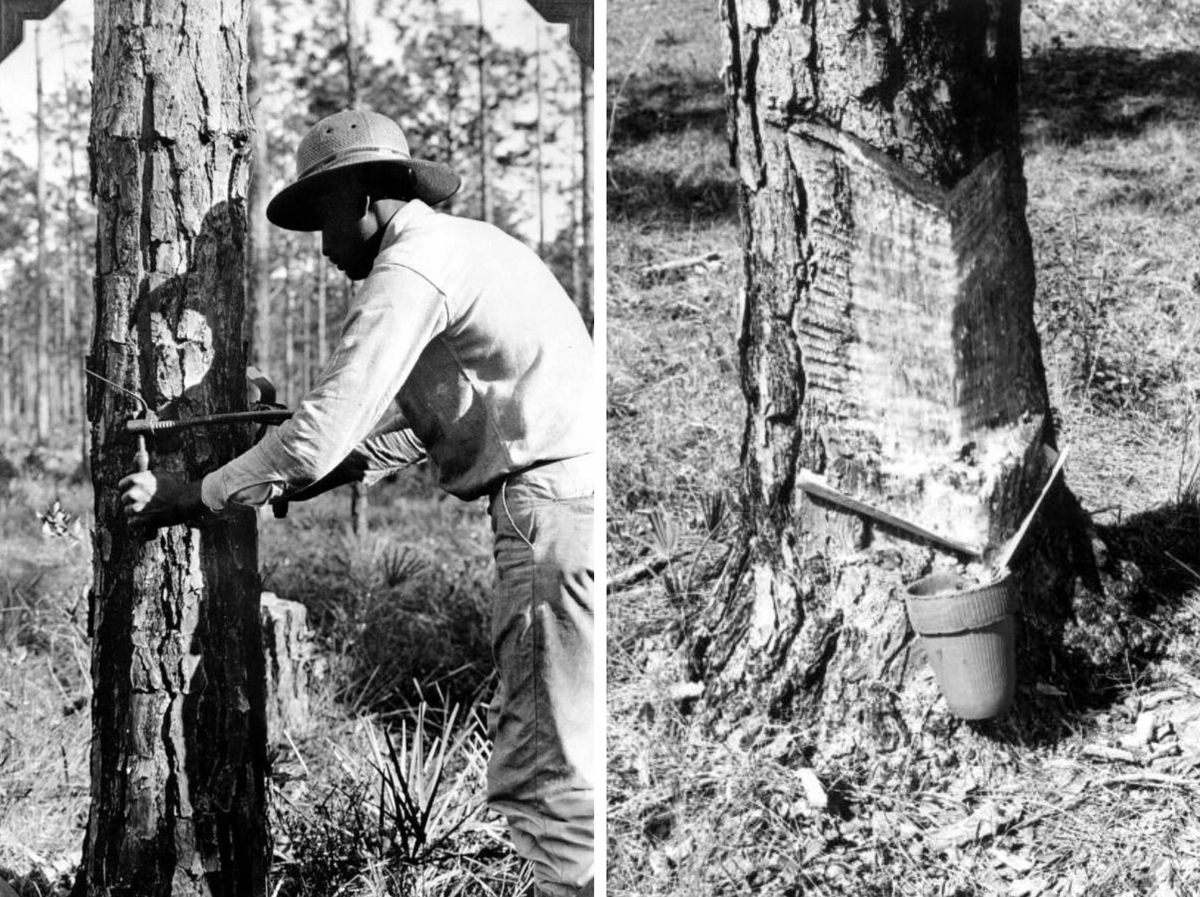

Other alternatives for these kinds of sites might include covering historic trash with dirt so people aren’t tempted to remove it, rerouting a trail, or placing signs to let hikers know not to get too grabby. Nigel Rudolph, the public archaeology coordinator for the FPAN central region and the other cohost of “The Materialists” podcast, has considered several of these options when he comes across sherds of what are known as Herty cups in Florida forests. These red, grooved ceramic vessels were once fastened to tree trunks to harvest pine resin for the state’s significant turpentine industry. Rudolph says he’s “probably found dozens” in the course of archaeological surveys on public and private lands in Florida, spanning county parks, state parks, and national forests—including in the Osceola National Forest in Lake City. Because they’re old and speak to the region’s history, Rudolph says, he leaves them in place—and sometimes advocates for interpretive signs to help visitors understand what they’re looking at. Rudolph says there are several historic displays about the turpentine industry at state parks in Florida, and a Herty cup (also known as a Herty pot) is on display at the Florida Museum of Natural History, too. When Rudolph came across an intact one in another park, he photographed it and noted the location—and then “tried my best to cover it up” under a blanket of dirt, he says.

Joshua Tree is doubling down on education, too. A few years back, staff posted signs around campgrounds and other public places, reminding guests to leave old trash in place: “You may have discovered a park artifact that tells of another time,” the sign reads. Now, they also try to get the message out on social media.

Though trash helps archaeologists understand the past, no one is recommending littering as a way to leave historic breadcrumbs for scientists of the future. Even so, those future researchers will have plenty to do, considering how much material—plastics in particular—we’re contributing to the archaeological and even geological record. Sometime in the future, when our contemporary garbage becomes indisputably archaeological, there’s going to be stories in it, whether we like them or not. “We’re always relating it back to the people who used these things,” Rudolph says. “A human being made this piece of pottery that is now broken beneath a road. A human being left this Herty cup here. We’re trying to find the people in the garbage.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook