The Rambunctious, Elitist Chocolate Houses of 18th-Century London

They were the original gentlemen’s clubs.

In England, posh men and members-only establishments, such as London’s famed Gentlemen’s Clubs Boodle’s and Brooks’s, have gone hand-in-hand for centuries. Even the concept of the ‘club’ is said to find its roots in Britain, and despite the BBC referring to them as “much lampooned bastion[s] of privilege and tradition,” their popularity has surged in recent years. What would I know though? As a not-so-well-connected woman, it’s unlikely I’d ever get a foot in the door.

But Gentlemen’s Clubs actually owe their existence to chocolate. Or, more specifically, to the rowdy chocolate houses of the 17th- and 18th-century Europe.

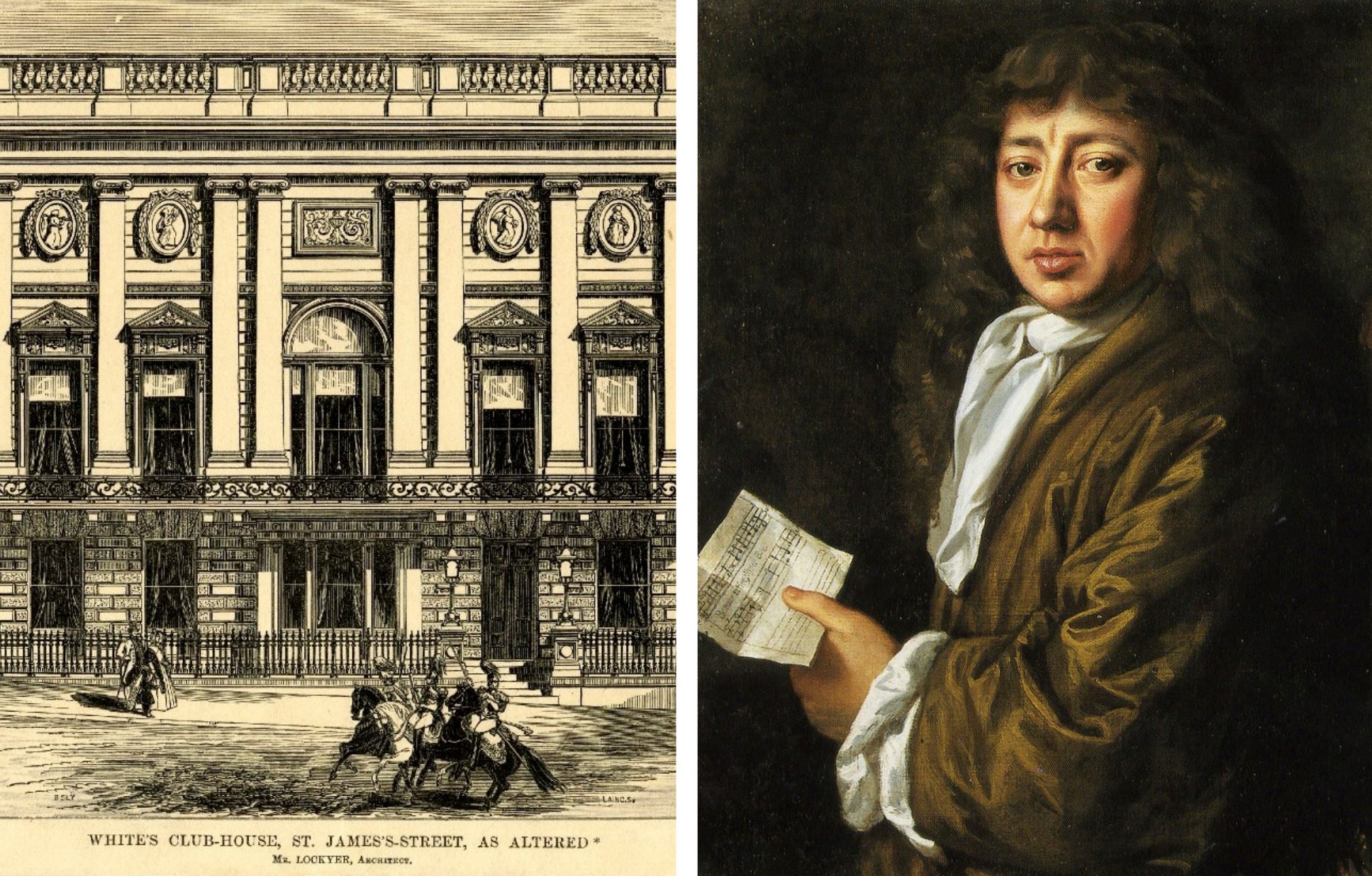

A sense of these establishments can be glimpsed from the 18th-century painting series “A Rake’s Progress,” which depicts White’s, the most debauched chocolate house of the bunch. A man kneels on the floor, wig in hand, in despair after losing his fortune, while a fellow gambler haggles with a moneylender. Behind him, a fight is breaking out, and most fail to notice a dangerous fire starting to smolder. Such is life in the 18th century chocolate house. Jonathan Swift famously described the establishment—which was established in 1693 by Francesco Bianco, an Italian who went by Frances White—as “the bane of the English nobility.” Others considered it “the most fashionable hell in London.” (That fire wasn’t fictional. White’s burned to a crisp in 1733.)

White’s may have been one of London’s most infamous chocolate houses, but it was not the first. Most historians cite one run by a Frenchman on Queen’s Head Alley just off Bishopsgate, although Dr. Matt Green notes in his book London: A Travel Guide Through Time that “someone called John Dawkins, living near the Vine Tavern in Holborn, was offering chocolate ‘at reasonable rates’ as early as 1652.”

Meanwhile, London was in the throes of a uniquely tumultuous political period. While Dawkins was dishing out drinking chocolate, two political parties were vying for both power and popular opinion. There were “the Tories, who were ‘divine right’ royalists, and the Whigs, who were generally anti-Stuart,” write the Coes in The True History of Chocolate. (The Stuart dynasty dominated the English monarchy throughout the 17th century.) As such, chocolate houses began to shake off their humble beginnings and “reasonable rates,” instead developing into hangouts for the hobnobbing politicians and social climbers who had the means to foot the bill for luxurious (and correspondingly costly) chocolate. In fact, Charles II so feared chocolate houses’ political plotting, idle chitchat, and, eventually, rampant gambling that he tried to ban them in 1675.

He failed spectacularly, and by the late-17th century, notes Green, London’s aristocratic St. James’s neighborhood was awash with a “cluster of super-elite, self-styled chocolate houses,” including White’s, The Cocoa Tree, and Ozinda’s.

Chocolate may be commonplace today, but at the time, it served as the ideal catalyst for those soon-to-be dens of debauchery. After all, it was an new, exotic drink from the Americas, having arrived in Europe in the 16th century and oozed its way across the continent. It landed in London some 100 years later, shortly after another equally mysterious drink: coffee. In addition to novelty, the popularity of both was bolstered by pseudo-scientific marketing ploys. Coffee became synonymous with sophistication (although it was later decried by people ranging from women’s groups to papal advisers as heathenish and an abomination), and coffee houses became popular places for people of various social standings to discuss business, politics, and science. Meanwhile, notes Green, chocolate, as the more expensive, exclusive substance, was imbued with “powerful and infallible” aphrodisiacal properties. Samuel Pepys, the famed diarist and member of parliament, even hailed it as a hangover cure. Movers and shakers clamored to get their hands on it, even in the early days, when the chocolate was likely bitter or sour.

But just as the chocolate houses themselves became more decadent over time, so did the chocolate. By the 18th century, sugar was very much present in the formerly bitter beverage; egg yolk emulsifiers were added too, to take the edge off the unsightly white cocoa butter content of the chocolate (or, as Sarah Moss writes in Chocolate: A Global History, “perhaps, given the egg yolks, custard”). As Sophie Jewett, owner of The Cocoa House and Works in York, England, tells me, serving up bitter chocolate in the lavish, purpose-built chocolate houses of the 18th century seems incongruent. “In those places, [chocolate] would have been at its most opulent. If somebody could afford cocoa, they could afford sugar.” After all, chocolate was “the beverage of the aristocracy,” according to Bertram Gordon in Chocolate: History, Culture, and Heritage.

Chocolate, and all it came to symbolize, may have drawn the initial crowds, but it was the chocolate house culture which kept them coming back. The regulars “weren’t going to exclusive chocolate houses to drink chocolate,” Jewett says. “They were going to hang out with other people who could afford chocolate.”

Oh, and gamble. They were definitely going to gamble. What Green refers to as the “legendary White’s betting book,” which dutifully listed every triviality bickered over and bet upon by members, can appear, at first glance, to be satire. Bets were placed on whether a man dragged in off the street would live or die (die); on whether a man could live 12 hours underwater (no); and on which raindrop would reach the bottom of a windowpane first (who cares). Most extravagantly, £180,000 was dropped on the roll of a die, an astronomical figure both at the time and today.

Once industrialisation made chocolate a foodstuff for the masses in the late-18th century, chocolate houses fell out of fashion. However, the most extravagant endured. White’s is now the oldest Gentlemen’s Club in London , a private establishment whose members list reads like a who’s who of English aristocracy. (Prince Charles, naturally, held his bachelor party there.) White’s also has the dubious honor of maintaining a strict and controversial no-girls-allowed policy. Unless you’re the Queen of England, that is. (She’s been allowed in twice to date.) Meanwhile, The Cocoa Tree, which Lord Byron once frequented and which was found to have a secret tunnel leading towards Piccadilly, is now the RAC (Royal Automobile Club) headquarters.

Chocolate houses may be a thing of the past, but their opulent, elitist legacy lives on in London.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook