For Centuries, Massive Meals Amazed Visitors to Korea

Scholars, writers, and missionaries all exclaimed over how much food was available.

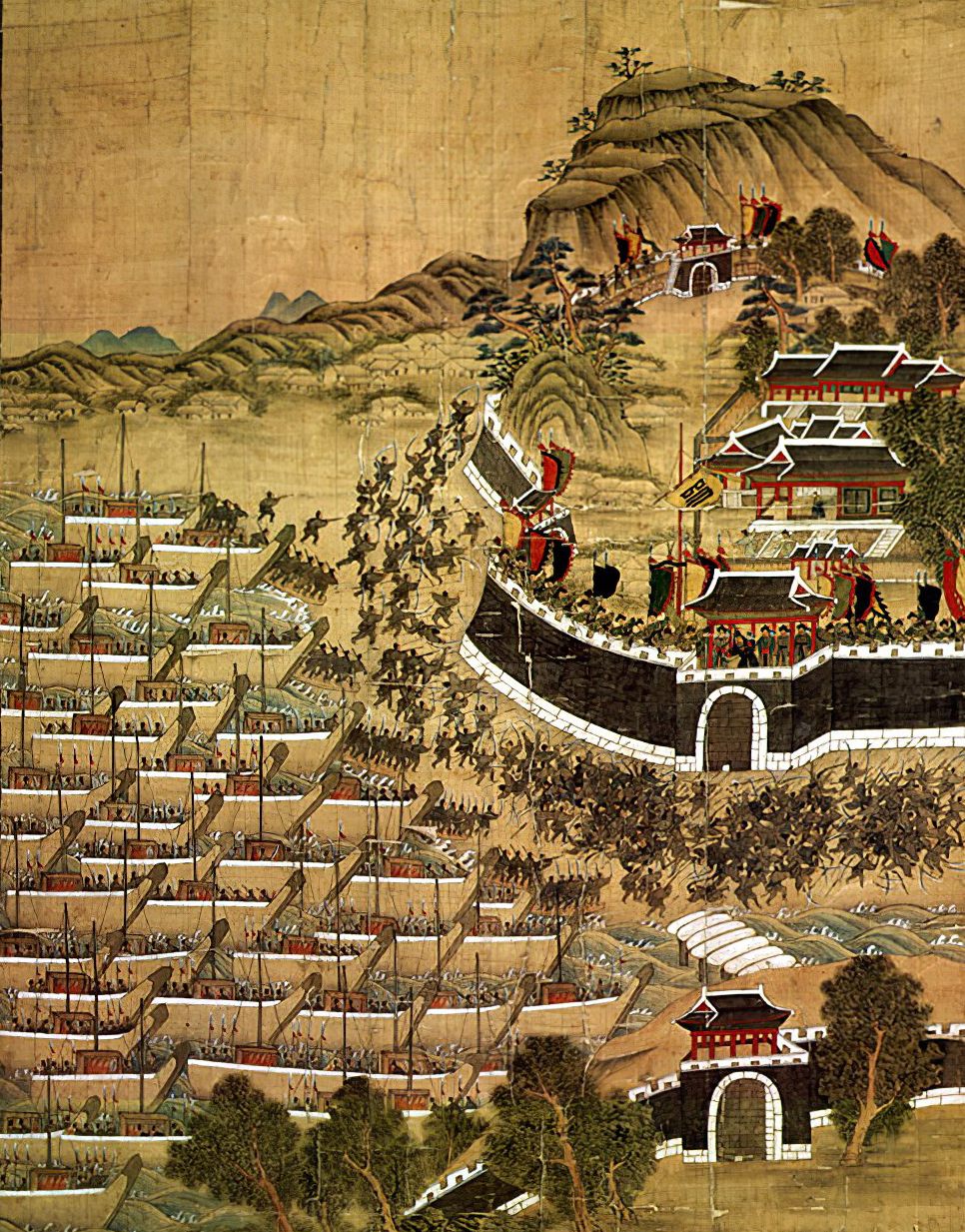

In 1592, Japan’s imperial regent Toyotomi Hideyoshi launched a massive invasion of Korea, pushing the ruling Joseon Dynasty to the brink of destruction. To gauge the lasting power of the invading forces, Joseon’s military dispatched spies to observe how much rice the Japanese were carrying. The Korean spies returned with a reassuring report: Toyotomi’s army carried only one month’s worth of rice. Expecting a month-long conflict, the Korean forces decided to wait out the siege. But a month later, the Japanese forces still fiercely battled away.

When the Korean forces finally fought back and repelled the Japanese (with the help of soldiers and supplies from China), the Korean soldiers were shocked to find the small rice bowls that the Japanese left behind. To Koreans, they looked more like sauce bowls, leading them to conclude that the Japanese had starved themselves to stretch out the siege.

But this is but one of the many historical records showing that for centuries, Koreans enjoyed a jaw-dropping amount of food by contemporary standards. Blessed with plenty to eat for much of their history, Korean dining habits sometimes shocked foreign visitors and even inspired domestic criticism.

One of the earliest records of Korean daily meals comes from the Samguk Yusa, a book of history and legends from the late 13th century. The book described King Taejong Muyeol, who ruled during the Silla Dynasty in the late seventh century, eating as much as “six du of rice, six du of wine, and ten pheasants” each day—in other words, more than 20 pounds of rice and wine. Historians now believe that this described the amount of food consumed by the king and his retinue altogether.

But even more recent and accurate records also show ordinary Koreans eating impressive amounts. Yi Geuk-don, a 15th-century Confucian scholar, complained to the king that the people were not saving food in good harvests, but ate in one meal the amount of food that the Chinese would eat in a day. In Swaemirok, a book chronicling life during the Joseon Dynasty in the late 16th century, author Oh Hui-mun wrote that an “ordinary grown man of Joseon eats about seven hob of rice per meal”: more than two pounds.

Europeans who visited Korea in the 19th century also noted that Koreans typically ate double to triple the amount of food that the Japanese or the Chinese ate. For example, in his travelogue from 1894, writer Ernst von Hesse-Wartegg noted:

“When I was in Japan, the Japanese told me their neighbors ate about three times as they did. When I later arrived at the port of Jemulpo [today’s Incheon], I saw that it truly was the case. Unlike the Chinese and the Japanese who eat at regular intervals, Koreans eat at all times. Unbelievable amounts of rice, along with a fistful of red peppers, would disappear in an instant.”

Perhaps because of the better eating, Hesse-Wartegg also noticed Korea’s soldiers were “muscular, stocky and well-nourished” and “in a much better condition” than Chinese and Japanese soldiers.

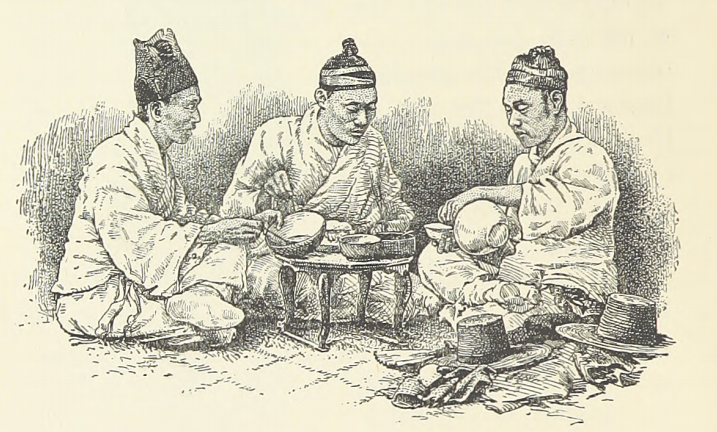

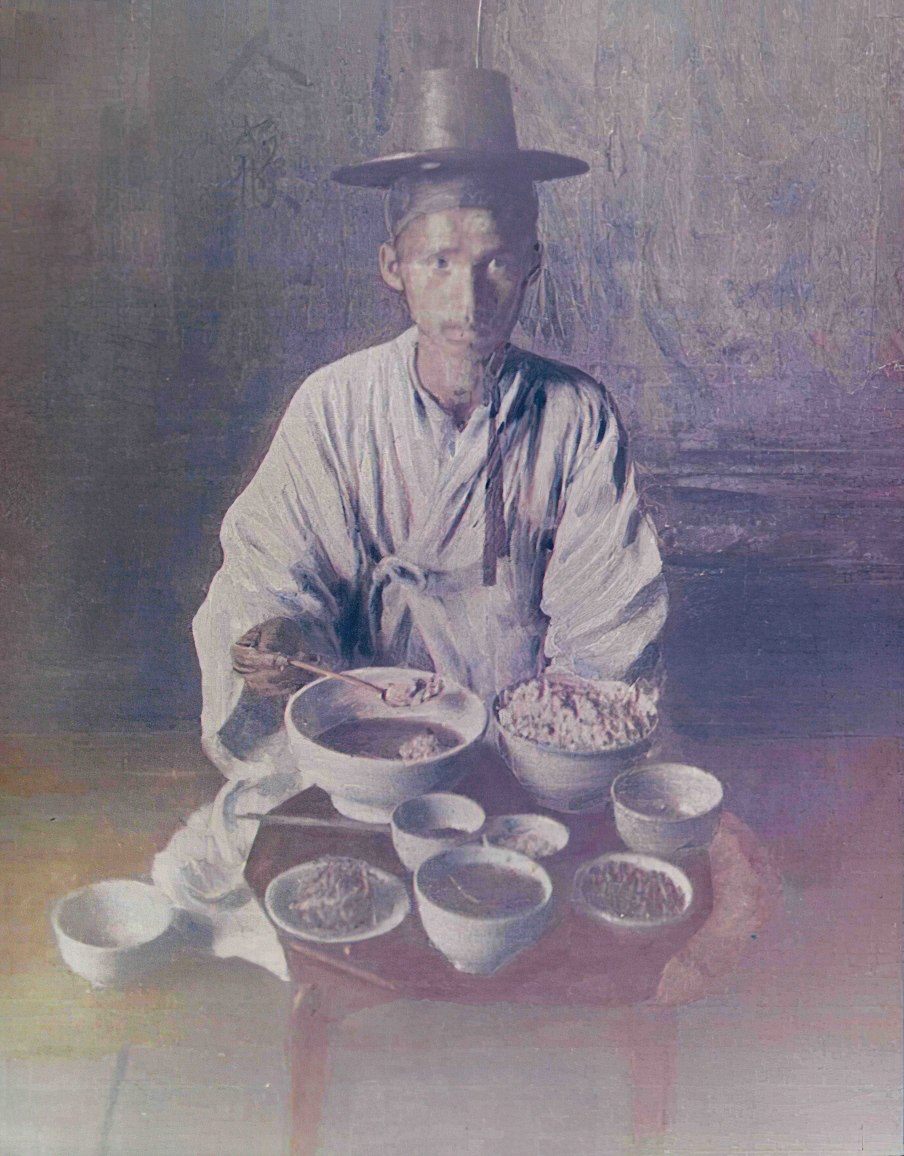

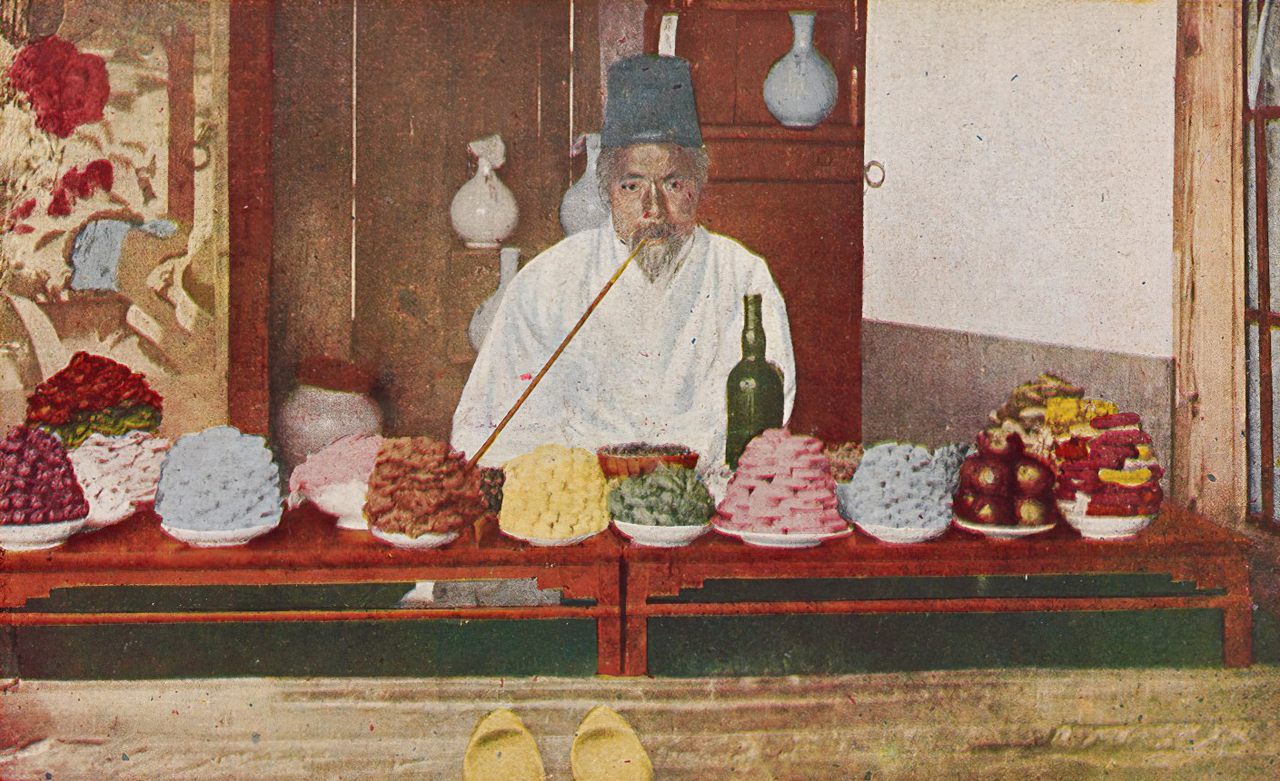

There is even a photographic evidence of how much Koreans ate in the 19th century. A photo postcard sold in France in the late 19th century shows a Korean man in front of his table, with the caption “Bon appetit!” In his book, Korean History on the Table, food writer Ju Yeong-ha noted the rice bowl in the photo was 3.5 inches tall with a diameter of over 6 inches, holding nearly a liter of rice to be eaten with soup that came in an even larger bowl, with an assortment of side dishes. For one person. In one meal.

One lively record of historical Korean eating comes from Marie-Nicolas-Antoine Daveluy, a Catholic priest from France who served as a bishop in Korea between 1845 and 1866. The author of the first French-Korean dictionary, Bishop Daveluy was eventually martyred for his faith. (His home is now a memorial site for the early Catholic martyrs of Korea.) His Notes for Introduction to the History of Korea, written around 1860, is not exactly a politically correct read, as it contains a great deal of the casual racism typically displayed by Europeans traveling through Asia in the 19th century. But Daveluy’s writing is valuable as a historical record, and it showcases some truly astonishing feats of Korean eating:

“Laborers usually eat around a liter of rice, which fills up a very large bowl. It is not enough for each person to finish one bowl, as they are ready to continue eating. Many people easily finish two to three bowls. One man in my parish is aged between 30 and 45, and in a bet he ate seven bowls—and that’s not counting the bowls of rice wine he drank. One old man, aged 64 or 65, said he had no appetite, and finished five bowls.”

According to Daveluy, it was not just rice that Koreans consumed in outrageous amounts: “When it comes to serving fruits, for example with large peaches, even a person with the most restraint eats around ten; it is not uncommon to see a person eating 30, 40, 50 peaches. As to melons [the small Korean melons, or cham-oe], people usually eat around ten at a time, but sometimes they eat 20 or 30.”

But how did Koreans have so much food to eat? Fertile lands and superior farming techniques certainly played a role, as Korea is one of the earliest locations in the world to adopt paddy-style rice farming. Farmers grew rice seedlings, then transplanted them into flooded fields, allowing for more intensive planting and easier management.

Ju Yeong-ha also notes the importance of Daedong-beob, the taxation system that the Joseon Dynasty introduced in the early 17th century. Prior to Daedong-beob, Koreans paid taxes to the king in the various forms of goods that the royal court required, such as lumber, horses, and silk. Daedong-beob unified the various forms of taxes to a single kind: rice. This, in effect, made growing rice equivalent to growing money, encouraging even more production than strictly necessary. With so much more rice, Koreans simply had access to more food.

Of course, modern Koreans do not eat this much. As Koreans adopted a more sedentary lifestyle and meals became less centered on rice, their food intake steadily decreased. Zen Hankook, a Korean porcelain maker, found that their standard rice bowl’s size went from 680 milliliters in the 1940s to 290 milliliters in 2012—nearly a 60 percent reduction in the last 70 years.

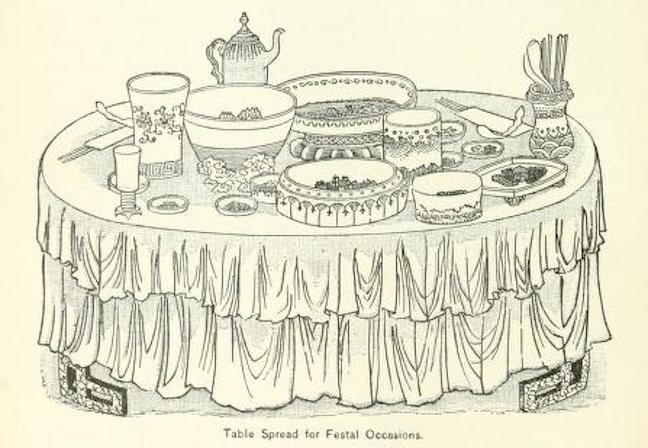

But in areas of Korea with strong food traditions, the practice of serving an inordinate amount of food is alive and well. A good example is the southwestern city of Jeonju, the birthplace for many world-famous Korean dishes, such as bibimbap. Jeonju is notorious for both the quality and the quantity of its food—at its renowned Makgeolli Alley, a $15 kettle of makgeolli (rice wine) comes with dozens of delicious little dishes covering up the entire table. According to a survey conducted in 2002, one of the few complaints of international visitors to Jeonju was that the local restaurants served too much food.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook