Rediscovering Mecca Flats, a Legendary Chicago Apartment Building

It was destroyed in 1952, but this storied residence was once a gathering spot for the Chicago Black Renaissance.

In July 2018, when a maintenance crew uncovered artifacts from the often-mythologized Mecca Flats apartment building in Chicago, Rebecca S. Graff immediately knew she had to get involved.* Graff, a historical archaeologist and Lake Forest College professor, became part of an interdisciplinary team tasked with examining the site. During the course of the dig, which lasted less than a week, she and her colleagues gathered seemingly mundane household items that will hopefully reveal details about the inhabitants of one of the city’s most storied residences.

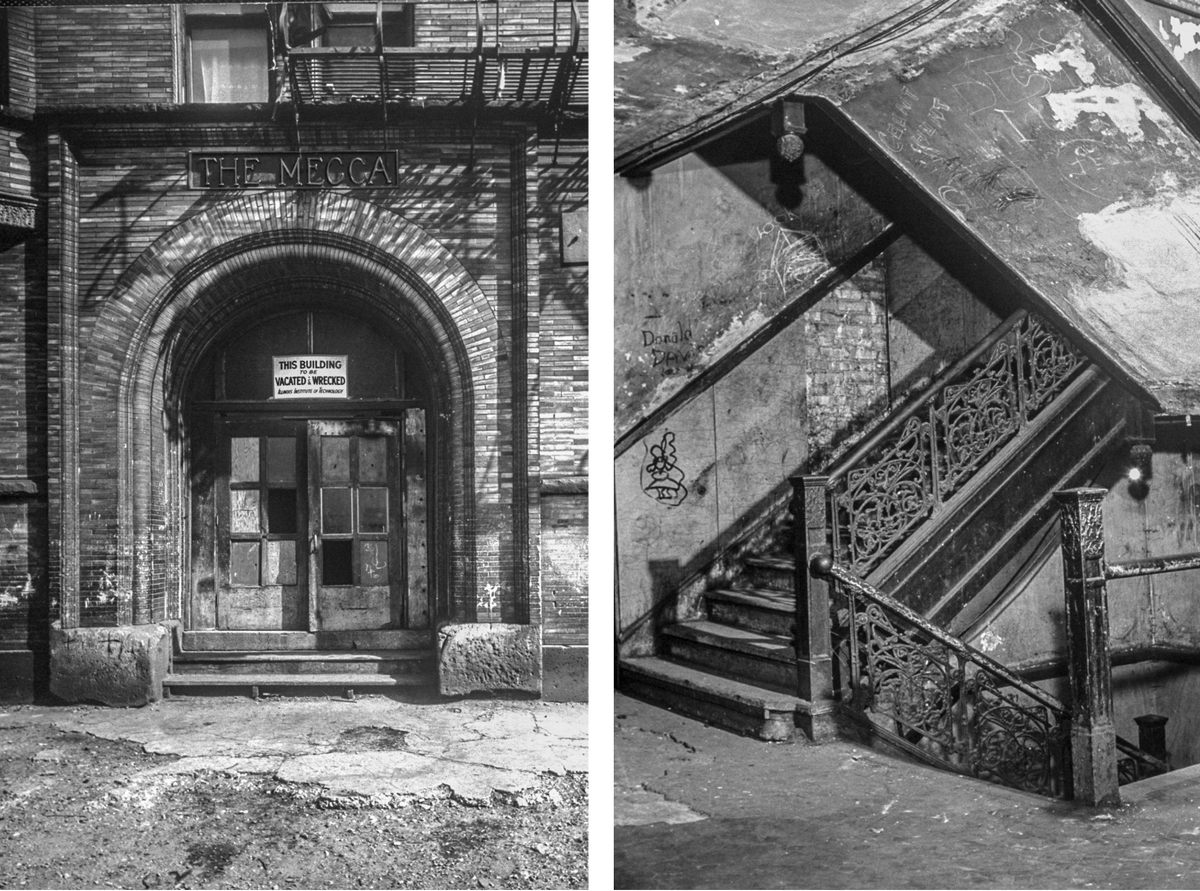

Mecca once covered more than two acres of land in the South Side’s Bronzeville neighborhood. It was a state-of-the-art housing structure when it was completed in 1892, but initially, it allowed only white tenants. After becoming desegregated in the first half of the 20th century, it transformed into a gathering spot for the Chicago Black Renaissance. Over time, it fell into disrepair, and despite pushback from tenants, was destroyed in 1952 to accommodate the growing Illinois Institute of Technology. S. R. Crown Hall, the home of the IIT’s College of Architecture, now sits on Mecca Flat’s old grounds.

The recovery effort created a unique collaboration between university, city, and nonprofit preservation partners. Now that the dig is over, Graff and her students are examining two large boxes of uncovered objects, which include clay marbles, a pill bottle, a silver fork, and parts of the building’s infrastructure. Graff says she plans to complete a report by the end of 2018 examining the date and usage of the artifacts. She hopes her findings will help people become more connected with those who lived in Mecca Flats. But Ward Miller, executive director of the non-profit Preservation Chicago, believes there’s a field of fragments around Crown Hall, so there will likely be more excavation efforts on the site in the future.

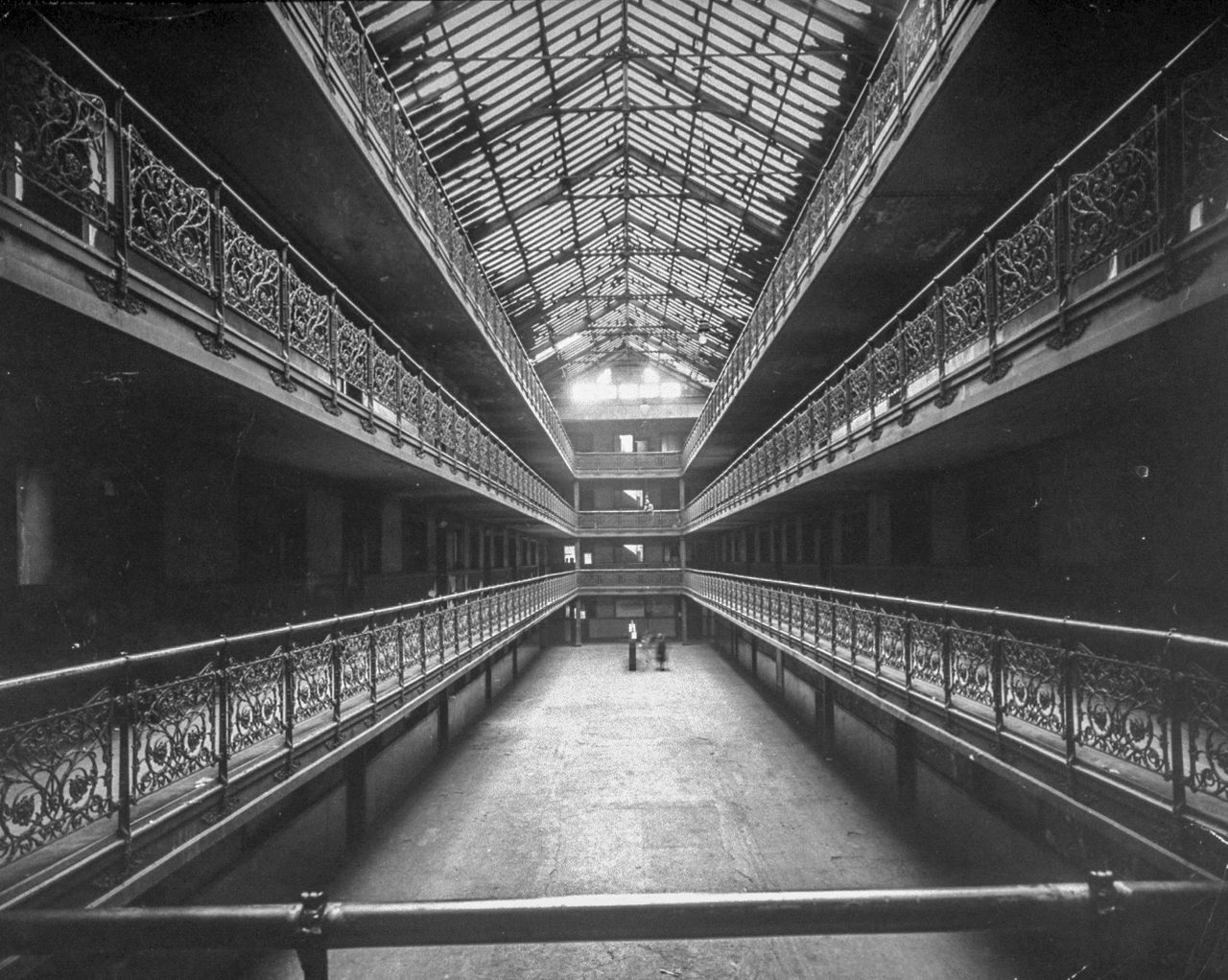

Construction of Mecca Flats began two years before the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition would bring around 27 million attendees—almost a quarter of the U.S. population at the time—to the Midwest. In a development wave following the Great Chicago Fire of 1871, Willoughby Edbrooke and Franklin Burnham designed a U-shaped structure with a courtyard, a feature that would come to define Chicago architecture. The two-wing building was notable for its proportions: Intended to house almost 500 residents, the Chicago Tribune in 1891 described it as “a fair-sized village.”

Romanesque design elements included arched entrances, indoor and outdoor fountains, and ironwork. As the architectural historian and professor Daniel Bluestone wrote in his 1998 paper “Chicago’s Mecca Flat Blues,” large atria—the first of their kind in a Chicago residential building—created communal places.

“I would imagine that brought people together as much as sitting on a front or back porch in an urban or even suburban environment where people are conversing and bringing ideas, conversations, and friendships all altogether,” says Miller.

“It was this new idea that instead of having a house, you could have a classy apartment building,” says Chicago’s official cultural historian Tim Samuelson. Highlighting the location as the dividing line between the black and white neighborhoods, Samuelson described Mecca as “gentrification, 1890s-style.”

Bronzeville during this time housed a wide variety of working-class residents, with a growing Black Belt developing on the railroad and industrial land west of Mecca. The building’s original owners hoped to attract more middle-class people to the area.

Through the turn of the century, Mecca Flats only allowed white residents. But shifting demographics in the city also prompted shifting demographics within the apartments. More than half a million African Americans came to Chicago as part of the Great Migration, and the city’s black population more than doubled during the 1910s. Located near the Illinois Central Railroad that brought migrants north, Mecca Flats became desegregated in 1912 and soon housed almost exclusively black tenants.

An open job market during World War I allowed a growing class of black professionals to prosper, many of whom moved into Mecca Flats. Around the same time, jazz flourished in the city with the likes of Louis Armstrong, Jelly Roll Morton, and King Oliver commanding local nightlife. Mecca was immortalized in “Mecca Flat Blues,” recorded in 1924 by the pianist and composer James “Jimmy” Blythe and the singer Priscilla Stewart. The jingly tune tells the story of a “Mecca Flat woman” who “stings like a stingaree” and is looking for her “Mecca Flat man.”

The song—which ended up with so many verses, a Tribune reporter in 1943 reflected it “would make a book”—captured the interpersonal drama of Mecca Flats. As Samuelson says, “the comings and goings of people in and out of their apartments and who they brought with them were no secret to everybody else.” He recalls one tale of a church pastor’s wife, who suspected her husband was having an affair with a chorus member: “She gets people to break the door down and they find the minister with no clothes on, hiding in the bathroom.”

While stories of domestic spats and petty crime often made the local news, including the landmark black newspaper the Chicago Defender, Samuelson also highlighted moments of connection and entrepreneurship, like a woman who turned her apartment into a restaurant because there were few options for the Southern food many residents favored.

In the mid-1930s, a young Gwendolyn Brooks was desperate for work in the Depression-era marketplace. Jobs, especially for African-American women, were scarce. Through the Illinois State Employment Service, she became an assistant for E.N. French, a supposed East Indian prophet who hawked magic potions to his fellow residents in Mecca. Brooks bottled and delivered these love spells and other elixirs, but quit after the fraudster from Tennessee tried to convince her to join his church. The experience inspired Brooks’s 1968 National Book Award finalist “In the Mecca,” a narrative poem following a woman looking for her missing child. Brooks paints eccentric characters potentially based on real residents.

She later reflected on her time in the building, saying “In the Mecca were murders, lovers, loneliness, hates, jealousies. Hope occurred, and charity, sainthood, glory, shame, despair, fear, altruism.”

This intermingling of life and loss in the Mecca is something 90-year-old Lillian Roberts remembers well. The daughter of Mississippi migrants, Roberts moved into the apartments around 1931. She recalls homeless people sleeping in stairwells and how work was so scarce, people would hope for snow so they could get paid to shovel. Her mother Lillian Davis brought residents together through the Mecca Prayer Band, a group that helped the sick.

“I have nice memories about them: honest, poor, religious people that really believed in something,” says Roberts. Through welfare, her family received food they shared with those who didn’t receive aid. In return, neighbors helped her pay for college.

An activist, Davis was a prominent voice in attempting to preserve Mecca. In 1941, the newly formed IIT took control of the building and planned to demolish it, a goal supported by federal legislation from the 1930s that allowed for mass slum clearance.

During a decade-long legal battle, Davis participated in sit-ins at city hall and was often quoted in local and national outlets. In August 1951, she told the Chicago Daily News, “It’s a law of life that a person has to have a place to live.”

Supported by welfare and housing groups as well as local politicians, Mecca residents took the fight to the Illinois House and Senate. State Senator Christopher Wimbish helped delay the destruction of the Mecca until after World War II, arguing it was a case of “property rights versus human rights.”

According to both Samuelson and Miller, the campaign to save the Mecca is one of the first tenant-led movements, influencing future battles for civil rights in African-American communities. But following the war, IIT campus expansion began again. The school became a place where, as Bluestone described, “engineering students would be insulated from the very society they were being educated to serve.”

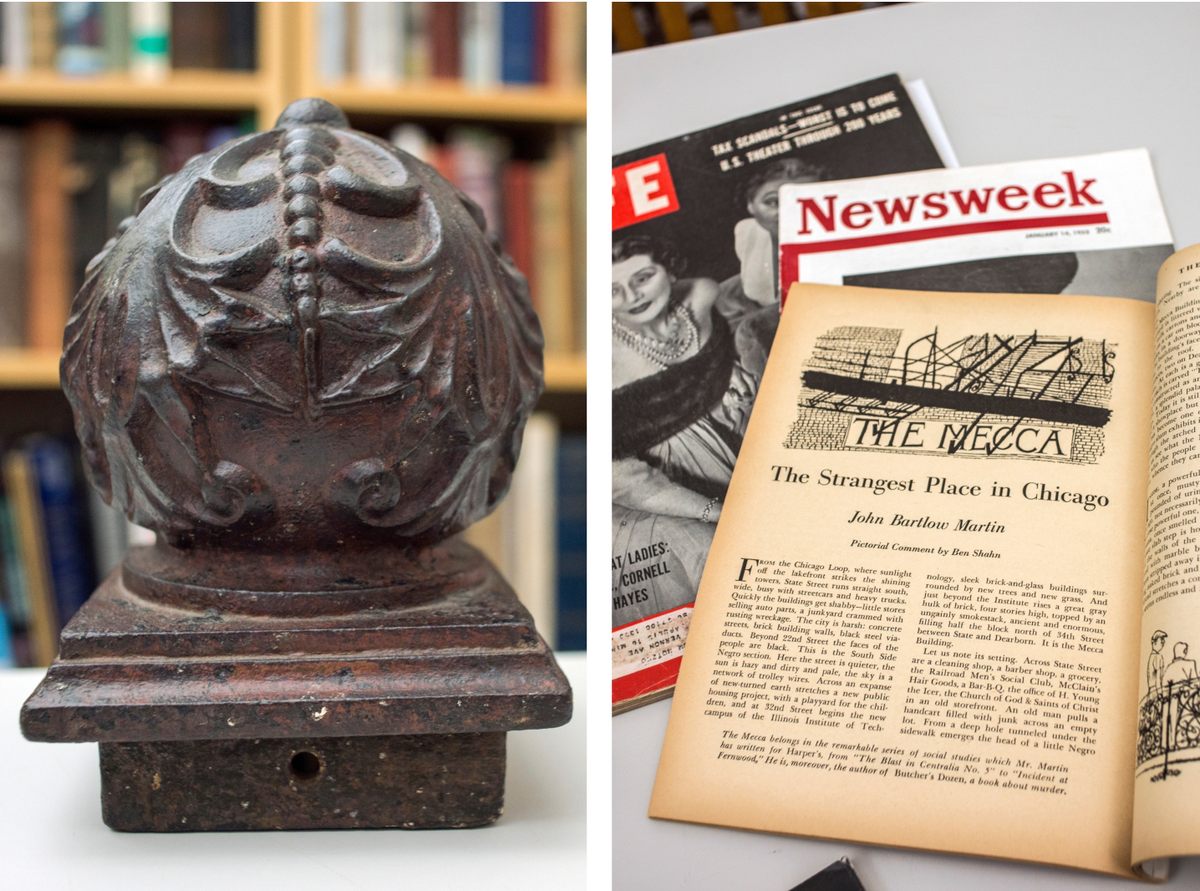

In its final years, the Mecca bore little resemblance to its original grandeur. Features in Life, Newsweek, and Harper’s mythologized a building on the brink of physical and moral collapse. John Bartlow Martin in the December 1950 edition of Harper’s called it “one of the most remarkable Negro slum exhibits in the world.”

More poverty porn than thoughtful reporting, these articles often ignored the needs of Mecca’s over 1,000 working-class residents. By the end of World War II, it had become clear that Mecca would not survive and the goal of those residents shifted. They no longer sought to save their home, but rather to obtain government assistance in finding new housing. As Jesse Meals, a longtime resident, told Newsweek in 1952, “You watch. A lot of people who lived here, they gonna die from grief.”

Samuelson and others note that historic preservation was rarely considered during this time, when many significant structures were destroyed. “The idea of repairing a building that was considered a slum was probably not something people thought of,” says Miller.

In the end, Mecca was replaced by a building rivaling it in aesthetics and significance. As the head of IIT’s College of Architecture, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe ushered in a new era of modern architecture featuring brick, steel, and glass.

Built atop the Mecca rubble, Crown Hall is a manifestation of van Der Rohe’s “less is more” philosophy. The box-like structure he once described as “almost nothing” lacks even interior columns dividing the open plan. Like the Mecca’s atria, Crown Hall encourages a universal and democratic use of space, as was apparent on a recent afternoon. Inside, students tinkered away at work benches, the vibrantly colored trees practically reaching in through the expansive windows.

Reflecting on the recent architectural discoveries, Michelangelo Sabatino, IIT’s dean of architecture, says, “It’s an opportunity not only for this institution but for a number of other institutions including the University of Illinois at Chicago (which also had a large scale development project) to think about how disruptive it is to displace people and adopt more conciliatory attitudes and more willingness to coexist.” Sabatino says local and national institutions are interested in acquiring some of the artifacts after they’re examined. He plans on building a display in Crown Hall so current students can learn about Mecca Flats.

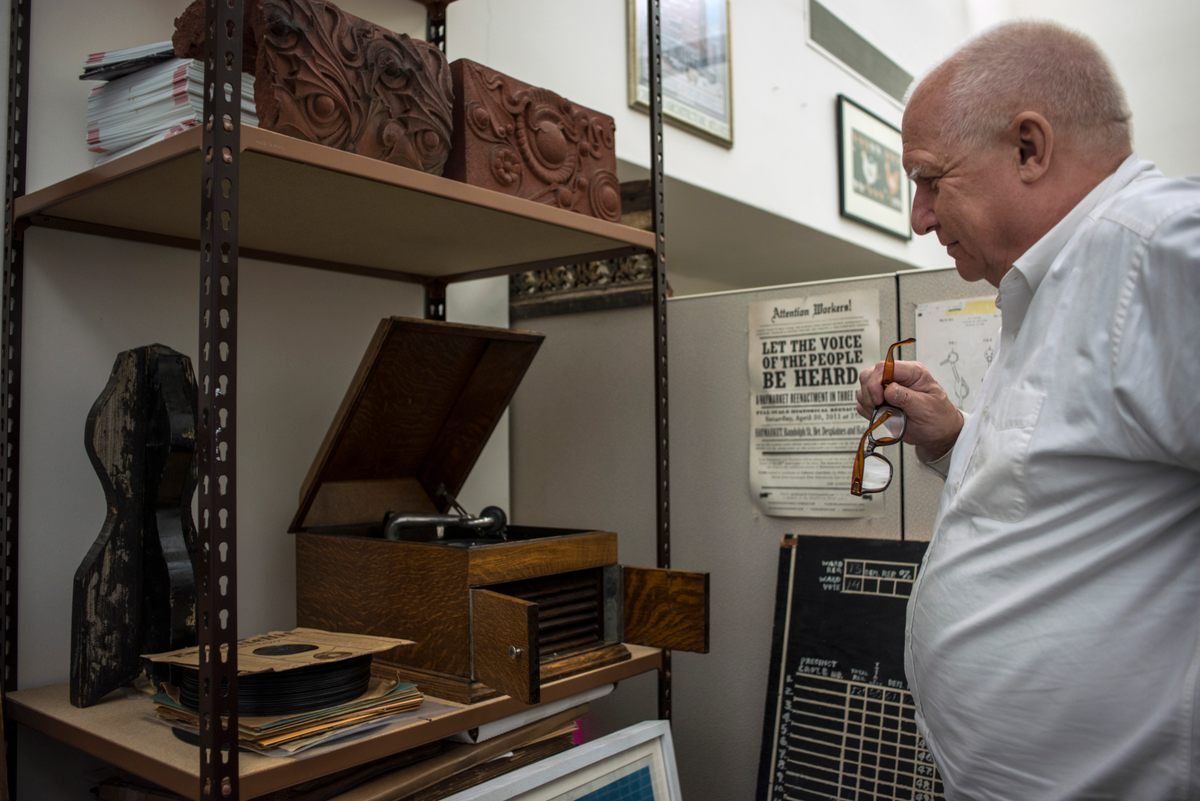

At his office in the Chicago Cultural Center, Samuelson shares a collection of Mecca memorabilia, from pressings of “Mecca Flat Blues” to parts of the metal railing and a foundation brick. These items are now part of the Chicago Architectural Preservation Archive. In 2014, he put together an exhibit on the building, which he is considering remounting in light of the new finds.

This recent dig not only reveals what objects Mecca residents kept in their homes and provides more examples of the materials used to construct the building, but it also highlights the care and dedication in preserving its legacy.

“This is not just the case of an architecturally interesting building,” says Samuelson. “It is a loaded story. It pushes every button of development, gentrification, injustice, and survival. The building had such a power that people remembered it, that someone who would write a song about it.”

*Correction: This article previously misspelled Rebecca S. Graff’s last name.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook