A Tiny New York Town With Not One, But 5 Indie Bookstores

The village of Hobart, home to fewer than 500 people, serves as a modest reminder that books can change people and places.

The village of Hobart, New York, is home to two restaurants, one coffee shop, zero liquor stores, and, strangely enough, five independent bookstores. “The books just show up,” Barbara Balliet, who owns Blenheim Hill Books, says. “I’ve come to the store and bags of books are waiting for me.” Fewer than 500 people live in Hobart. Yet from Main Street, in the center of town, you’re closer to a copy of the Odyssey in classical Greek, or a vintage collection of Jell-O recipes, than a gas station.

This literature-laden state of affairs emerged just after the turn of the millennium, when two residents of Manhattan, Diana and Bill Adams, stopped in Hobart during a trip through the Catskills. “We were both intrigued,” says Bill, who worked as a physician for 40 years. “I saw what a charming, and somewhat rustic, but civilized, area it was.” He and his wife Diana, a former lawyer, were looking for retirement activities that they could pursue into their old age.

During that first trip, in 2001, the couple spotted a corner store for rent at the end of Main Street. After speaking with the owner, they decided to rent it on the spot, and soon they were lugging their hefty personal book collection to Hobart, one rental car-load at a time. They didn’t expect to establish a book village in the process. “There was no plan,” Bill says. They weren’t even sure whether their bookstore would survive in the foothills of the Catskills, three miles from the main highway.

But they did own a lot of books. Toward the end of his career, Bill had worked six days a week at Harlem Hospital, and to help himself unwind, he taught himself classical Greek. He used to spend evenings jogging at the 92nd Street Y, listening to recordings of the Iliad. Eventually, he started collecting classical texts, and even translated Hippocrates in his spare time. Diana, for her part, preferred 19th-century political writing.

That was how it became possible to buy a leather-bound collection of classical verse, or a set of classic political essays, in a tiny village more than two hours from New York City. Wm. H. Adams Antiquarian Books had a relatively quiet first year. But then Don Dales, a local entrepreneur and piano teacher, decided that one good bookstore deserves another, and opened his own shop.

You might expect neighboring bookstores to compete with one another, like side-by-side movie theaters or department stores. But Dales suspected that the opposite was true. Readers, like shoppers at the mall, often wandered back and forth between the shops. As more bookstores came to town, one of Hobart’s original booksellers (no one can quite remember who) began to describe the town as “the only book village east of the Mississippi.” (Other American book towns include Stillwater, Minnesota, and Archer City, Texas.) By 2005, when a New York Times writer passed through, Hobart had earned its moniker: “Hobart Book Village.”

Barbara Balliet and Cheryl Clarke, a couple who spent their careers at Rutgers University, moved to Hobart at around that time. Clarke was surprised to find such a tiny community, far from cities or colleges, so overrun with books. “It adds an intellectual flavor, but not the elitist intellectual kind of flavor,” she says. “You find all kinds of people who like books, and they’re not just college-educated.” When the two women arrived, they met a bookseller who was ready to sell her stock, so Balliet bought it and they hopped into business themselves.

Both women saw right away that, compared to other Catskills towns that have lost jobs and emptied out, Hobart seemed to be coming back to life. “My first impression was that it was a lot livelier than some other towns, because the storefronts were mostly occupied,” Balliet says. The bookstores were a part of that. “They need the book culture around here. They need commerce, they need traffic,” Clarke says. “We need to build this town back up.”

Today, Blenheim Hill Books, a well-lit shop with a dog-in-residence and a view of the river, includes strong collections of feminist and African-American Studies books. Clarke is a poet and author who has written about the Black Arts Movement, Audre Lorde, and the black queer community, and Balliet was a professor of Women’s Studies at Rutgers. “As faculty retire, they have all the books in their office, and they don’t want to bring them home,” Balliet says. “You go and get sixty boxes of books.” As if a packed storefront weren’t enough, she also owns a carriage barn that is brimming with books. Balliet says that, although she can’t make a living off the store, she can make a tidy profit—enough to grow a garden, travel, and buy more books.

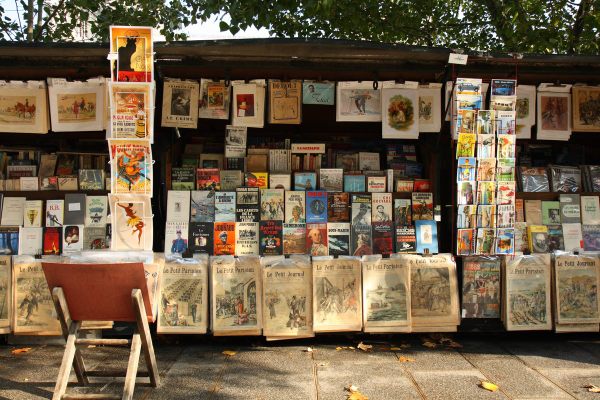

Hobart’s booksellers see themselves in a decades-long tradition of book villages, which are defined by their high-density of used and antiquarian book shops. The first, according to the International Organisation of Book Towns, was Hay-on-Wye, Wales, founded in 1961 by Richard Booth. “There’s so many billions of books that people don’t want,” says 79-year-old Booth, who sometimes goes by the nickname “Richard, King of Hay.” “They’re all over the place.” Booth estimates that there are more than 50, but fewer than 100, book towns in the world. Others include Wigtown, Scotland; Featherston, New Zealand; Kampung Buku, Malaysia; and Paju Book City, South Korea.

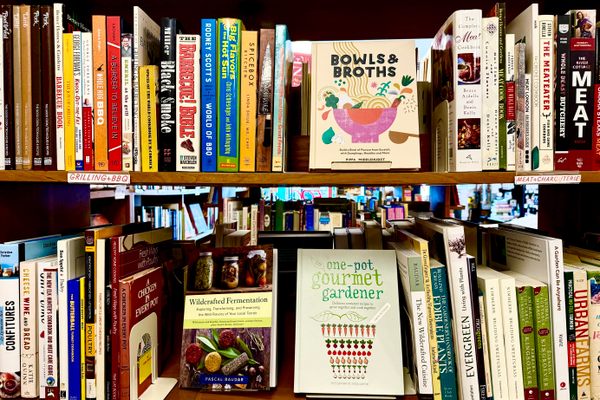

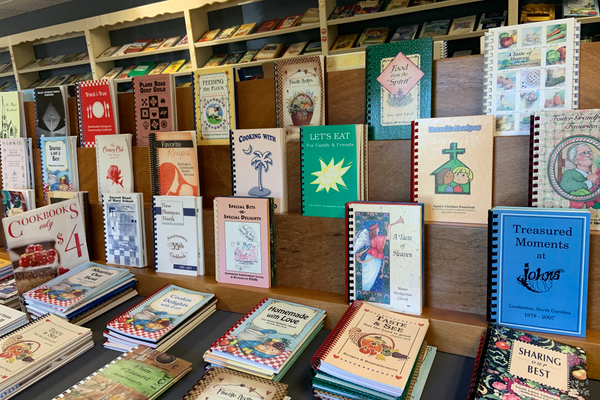

As Hobart evolved, individual book shops have found their own specialty, like siblings who each choose their own path. “We try to complement each other,” Balliet says. “Each one maintained its own identity and individuality,” adds Bill Adams. Creative Corner Books, a cozy one-room shop that specializes in craft, cooking, and DIY books, is Hobart’s only shop with a knitting corner. At one time, Hobart even had its own custom bookbinder.

This is an optimistic time for the book business, Balliet says. “Bookstores are opening, not closing,” she explains. “Book sales are up, eBooks are down.” The American Booksellers Association reported a slight increase in the number of independent bookstores, as well as a modest sales increase, in recent years. Meanwhile, according to the Association of American Publishers, eBook revenues declined by 5 percent between 2016 and 2017.

The Hobart Book Village serves as a modest reminder that books can change people and places. Bill Adams, its accidental co-founder, says that a book helped inspire him to become a doctor. These days, he and Diana often travel to Europe to re-stock the shop. When asked whether he found it difficult to leave New York City, with its dozens of bookstores and endless amenities, he told me no. “We weren’t really leaving something,” Bill says. “We were going to something.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook