How Americans Changed the Meaning of ‘Dream’

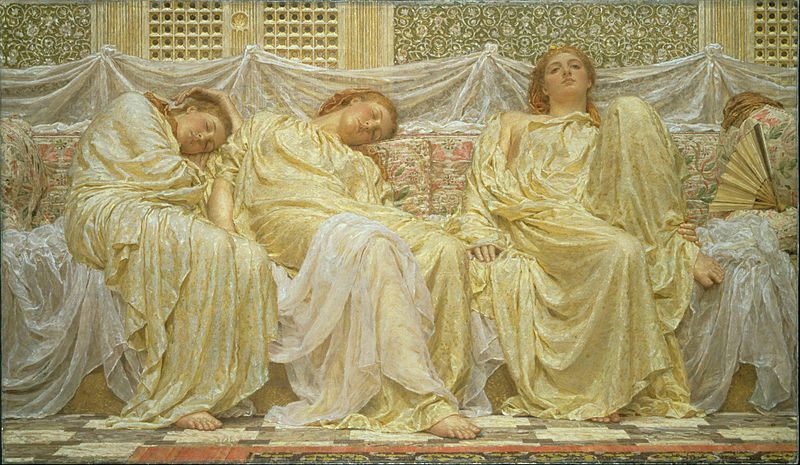

Albert Joseph Moore’s Dreamers, 1884. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

This is part two of a five-part series on sleep and dreams, sponsored by Oso mattresses. Read the first one here.

There was a time when “hopes” were not automatically paired with “dreams” in our lexicon. But when did these two concepts start comingling? How did English speakers repurpose a word used to refer to an involuntary activity, to describe, instead, the kind of purposeful visions that might guide the life of a striver? When did the verb “to dream” come to mean “to aspire?”

You can blame the Americans. Our collective embrace of the so-called “American dream” was the cornerstone of this particular 20th-century shift in usage.

In fact, before a historian invented the phrase in the Depression years, “dreaming” of a better life was not always looked upon favorably.

According to Oxford English Dictionary terms “dream, verb 2,” usage type number 4a: “To imagine and envisage as if in a dream; to have a vision or fantasy of. Now chiefly: to think or daydream about (something greatly desired); to hope or long for.” Also, usage type number 4b: “To indulge in fantasies or reveries; to daydream about something. Now chiefly: to have a vision of the future; to hope or long for something.”

The OED finds examples of each usage type as early as the 14th century, but for the first few centuries of its use, the connotations of this kind of “dreaming” were negative. As the etymology bloggers Take Our Word For It write, the roots of “dream” probably come from a Germanic root, draum-, and that root might derive from another one, dreug, which means “to deceive, or to delude.” Early waking dreamers thinking wild, idealistic thoughts about life were seen as deluded, indulgent, and a little bit lost.

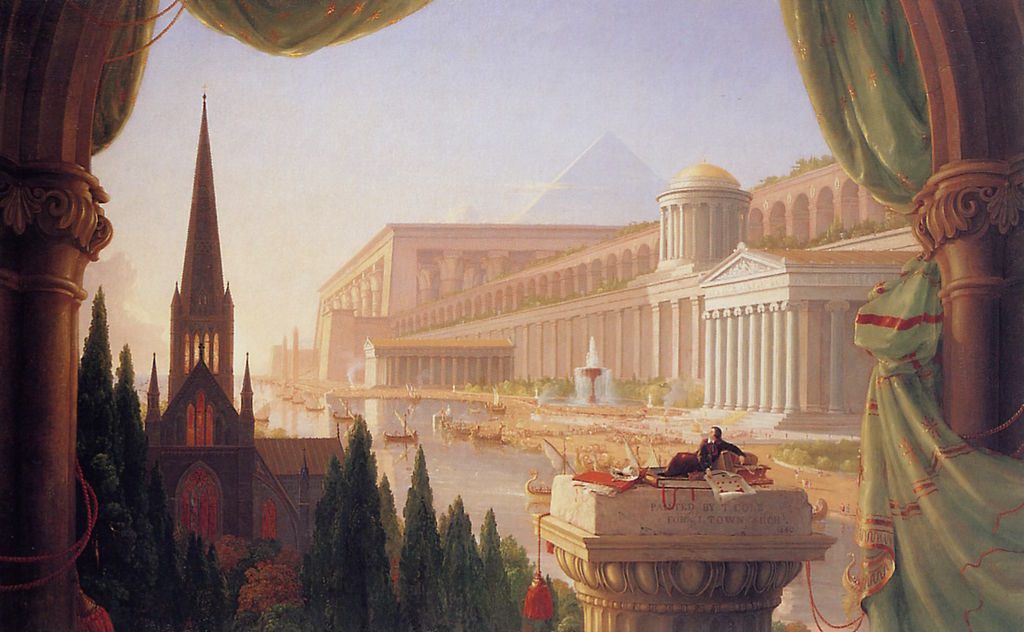

The Architect’s Dream by Thomas Cole (1840) shows a vision of buildings in the historical styles of the Western tradition, from Ancient Egypt through to Classical Revival. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

In one example, in 1667, in Milton’s Paradise Lost, Adam asks the angel Raphael to explain cosmology—the nature of the sun, moon, and stars, and their relationship to the Earth. The angel responds by counseling the first man against such musings:

Think onely what concernes thee and they being;

Dream not of other Worlds, what creatures there

Live, in what state, condition or degree,

Contented that thus farr hath been reveal’d

Not of Earth onely but of highest Heav’n.

Other citations in the OED from the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries offer echoes of Raphael’s caution, associating aspirational dreaming with foolhardiness. The phrase “pipe dream” entered British and American lexicon in the late 19th century, “apparently” (according to the OED) “with reference to the kind of visions experienced when smoking an opium pipe.” (The Chicago Tribune called aerial navigation a “pipe-dream” in 1890, in the phrase’s first appearance in print.) “Pipe dream” came to stand in for an impracticality that didn’t understand its own folly. Like foolish Adam or besotted opium addicts, aspirational dreamers thought of themselves as rational inquirers, following their curiosity; they didn’t realize that they were overstepping the bounds of reality, and slipping their own earthly responsibilities as they did so.

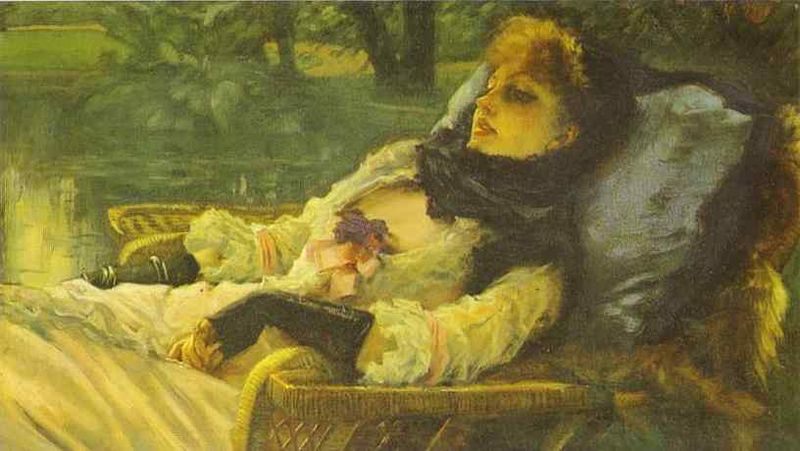

James Tissot’s The Dreamer (Summer Evening), painted in 1871. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

Everything changed in the 20th century. In 1931, American historian James Truslow Adams coined the phrase “The American Dream,” in his book The Epic of America. This one-volume history of the country, published at the beginning of the Depression, was a bestseller in its time, and was distributed through the then-new Book-of-the-Month Club, greatly expanding its reach. Adams used the “dream” as a structuring conceit for his gloss of American history, describing this dream as one of material prosperity, but also of what we might now call self-actualization.

Americans, Adams wrote, should be “able to grow to fullest development as men and women, unhampered by the barriers which had slowly been erected in older civilizations, unrepressed by social orders which had been erected for the benefit of classes rather than for the simple human being of any and every class.” Introducing a new edition of Adams’ book in 2012, Howard Schneiderman wrote that the “famous metaphorical phrase took off like a rocket, and it was soon being used in academic articles, as well as in popular magazines.”

Edwin Landseer’s Scene from A Midsummer Night’s Dream, where Titania, under a spell, falls in love with Nick Bottom, who has also been enchanted with the head of an ass. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

But the use of “dream” for “aspire” still holds within itself some of the verb’s pre-20th-century negative connotations. In his 1963 “I Have a Dream” speech, Martin Luther King, Jr. pointed out the gap between American aspirations of equality and the lives of people of color. “In his “Ballot or Bullet” speech, delivered in April, 1964, Malcolm X told listeners that the vaunted American social system had “victims,” and added: “I see America through the eyes of the victim. I don’t see any American dream; I see an American nightmare.” Hubert Selby, Jr.’s 1978 book Requiem for a Dream followed a mother and son from their initial social aspirations, through their drug addictions, into a very memorable collapse marked by a grisly amputation (for the son) and electroshock therapy (for the son). The author told Salon in 2000 that its pursuit could be a “disaster.”

And so, both meanings of “to dream” survive. George Carlin got big laughs for this 2005 punch line: “That’s why they call it the American Dream. Because you have to be asleep to believe it.” But self-help books with titles like Dare to Dream Wild abound, and dreamers put together “vision boards” to help guide their aspirations. In America and all around the world, the dream endures.

Sponsored by Oso mattress. OSO mattress is customizable comfort created with Reverie’s DreamCell(TM) technology. Shop the mattress now to discover the sleep for you.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook