How Cab Drivers Changed the London Landscape

Why are there little green huts all over London? To keep cabbies from being wet or drunk.

On a cold, snowy night in January 1875, Captain G. C. Armstrong couldn’t get a cab.

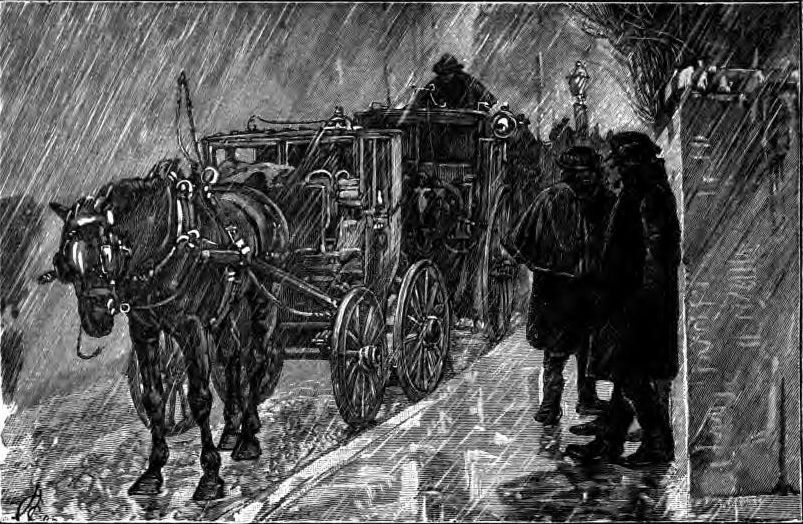

Cabs at the time were single-horse, two-wheeled hackney carriages, with a small interior that barely protected the fare from the elements and a seat at the top rear that didn’t protect the driver at all. Because it was illegal to leave a cab unattended, drivers were expected to “sit on the box” in all kinds of dreadful weather, as the brilliant Cabbie Blog explains, or pay someone to watch their cab while they nipped off to the pub for some warmth, food, and probably drink.

On this particular snowy night, Captain Armstrong – a baronet who was also the editor of The Globe – wanted a cab to take him from his home to his offices in Fleet Street. So he sent his servant round to the cab stand to fetch him one. But though there were cabs, there were no cabdrivers; those, the servant found, were all in the pub, sheltering from the storm blowing outside. And they were, to a man, too drunk to drive. When the servant returned home without a cab, he got an earful – and Captain Armstrong got an idea. Why were there no places where a cabdriver could get dry and warm without having to pay for a pint – possibly too many pints – and someone to watch his cab?

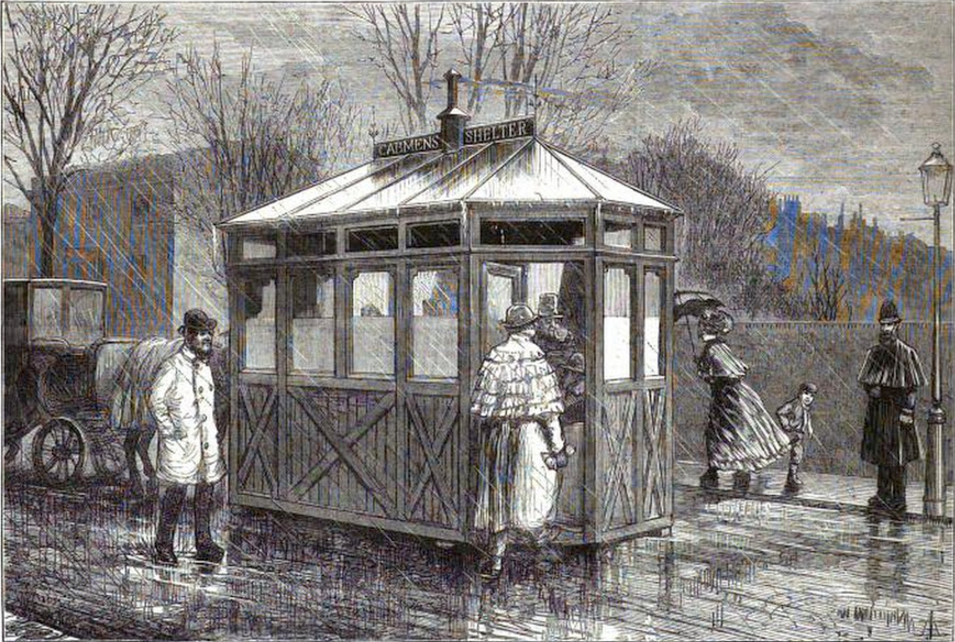

Within a month, Armstrong had teamed up with a group of like-minded philanthropic worthies, including the 7th Earl of Shaftsbury, and started the Cabmen’s Shelter Fund. Their idea was to build small shelters at existing cab stands where cabdrivers could take a break from the elements and grab something to eat or a warm (and non-alcoholic) drink. The proposed shelters, outlined in an article that appeared in the February 20, 1875 edition of the Illustrated London News, would be no more than 17 feet long by six feet wide, and 10 and a half feet tall, leaving just enough room inside for 10 to 13 (thin) men. There were railings on the roof to tether a hansom cab’s horses, and the shelters would have facilities for cooking and water. By the end of the year, at least 21 shelters – all painted the same shade of glossy hunter green, with black roofs and trims – were built and doing a brisk business in tea and coffee, chops and sausages, and bread and butter.

Even if the details of the Armstrong story aren’t quite accurate, says Jimmy Jenkins, a cabdriver for 42 years and the current director of the Cabmen’s Shelter Fund, there is a kernel of truth. Cabmen were often forced into pubs to get out of the weather, and they did sometimes drink too much; a group of worthies did form to deal with this problem in a very Victorian way. And, of course, as the story illustrates, it wasn’t solely for the benefit of the downtrodden cabman, his body buffeted by icy winds and driving rain and blisteringly cold snow, that the shelters were built.

“You got to remember, this was started by the aristocracy and it was to their benefit to have cabs. It’s quite logical really, it was for their benefit, really – they could get home quicker,” explained Jenkins, who on the phone sounds a bit like a pre-Hollywood Michael Caine. “This is what it’s all about: It was beneficial for the aristocracy because they could get home quicker, and they had more access to taxis.”

The story of London – its rich, poor and aspiring – can be told, in part, by its transportation. Hackney coaches for hire have been a part of the urban streetscape since the time of Elizabeth I, when wealthy aristos would rent out their carriages to less-wealthy aristos; the first taxi rank, according to the London Vintage Taxi Association, was established outside the Maypole in the Strand in 1674, with liveried coachmen and standard rates. The hackneys’ standards fell as their numbers rose; by the 1760s, there were at least 1,000 “hackney hell carts” clattering down London’s fetid streets. By the 1830s, the word “cab” entered the Londoner’s vocabulary with the introduction of the two-wheeled French-style “cabriolet,” and the cabriolet – with its exposed seat on the top – was the style that would dominate through the end of the century.

Cabmen did have a raw deal, and by the 1870s many people knew it. Several cities, including Birmingham, had already introduced similar shelters for the benefit of their cabmen, and in 1873, plans were afoot to build a “cabmen’s room” at the new Kingston railway station, just outside of London in Surrey. If the philanthropically-minded citizens trying to build the room raised enough money, the article from the November 15, 1873 Surrey Comet reported, they could make the “room” big enough to shelter the horses as well.

The idea to build a similar shelter in London first appeared in Lloyds’ Weekly Newspaper in early December 1874 (which may undermine the veracity of Captain Armstrong’s tale); the article described how a cabdriver trying to keep warm in London’s wet winters had to choose between waiting “out of doors with his blue fingers to his lips, or his arms flapping against the breast of his greatcoat, or else he must go into a public-house and pay for the privilege of warming himself by buying ‘something to drink’ that he does not want.” By the end of the month, according to a December 31st article in the London Evening Standard, a charity was formed and already appealing to the public for donations.

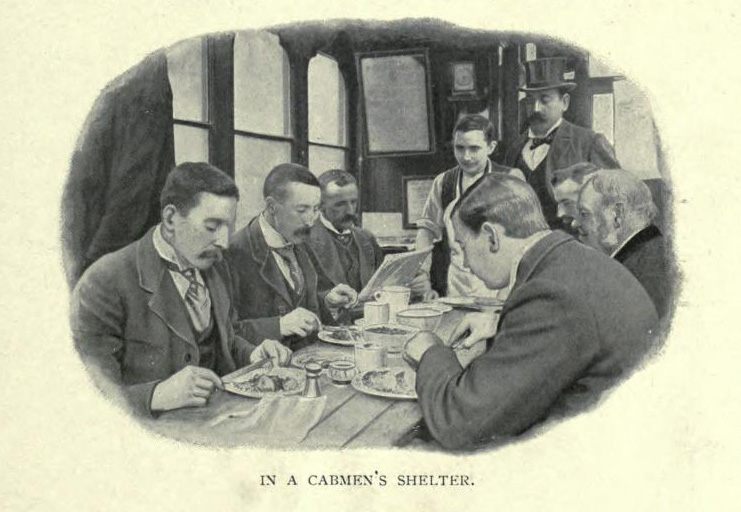

The cost was put at £75 per shelter, according to the Evening Standard, including the gas and water facilities; other sources say the building cost was as much as £200. While donation would pay for the initial outlay, the shelters were expected to be self-sufficient within a few months of opening – cabmen would pay a small “subscription” fee of not more than 6 pence a week to keep the place staffed and working. To deal with the problem of who watched the cabs, the first two cabs in the stand would stay “live,” their drivers ready to take a fare, and keep an eye on the cabs whose drivers were having a bite or a cuppa. (This, notably, is still the case today.)

This being Victorian London, the shelters also served a social and moral purpose, to raise the status of the cabdriver in society. They all maintained the same strict standards of conduct: Cabmen were prohibited from gambling or playing cards, and in some shelters they were asked not to discuss politics. The explicit purpose of the shelters wasn’t only to keep London’s cabbies out of the elements, but also to keep them out of the pubs, so drinking alcohol was right out of the question.

By December 1903, there were 45 cabmen’s shelters scattered throughout Greater London, serving some 4,000 cabmen every day, according to the Fund’s 28th annual report, reported in The London Daily News. Though the project clearly worked, it wasn’t quite the self-perpetuating scheme the Fund’s creators had hoped; for one thing, as Cabbie Blog points out, the shelters lost money during the summer months, when the weather wasn’t so terrible. Even then, the Fund lamented, “It is a matter of regret that the work should be carried on under the disadvantages of insufficient income.” The number of cabmen’s shelters continued to rise, however, although it’s unclear how many there were at the height of their popularity; some figures claim 61, others 65, while Jenkins put the number at 114.

But in that year, 1903, the London’s crowded streets would change in a way that would eventually doom the shelters: The first gas-powered motorcars, French imports, began prowling the roadways. The next 15 years saw the motorcar taxi trade grow in fits and starts (the name “taxi” came from the “taximeter”, the device that measured the distance the vehicle travelled). After the disastrous, deprived years of World War I, the motorcar dominated the cab trade and the need for cabmen’s shelters was necessarily decreased; the last horse on London’s streets was taken out of service in 1947.

“Basically, a horse could only go so far before having a rest… that’s why there were so many shelters,” explained Jenkins. “If a driver was taking a fare, for instance, from St. James [central London] up to Highgate [north London], that’s a six or seven-mile journey for a horse dragging a carriage. The driver would know he could go to Highgate there would probably be a shelter there, rest his horse and get a drink himself.” But after motorcars entered the picture, “You didn’t need so many shelters, you could get about quicker and you didn’t need to water a horse.” Many shelters fell into disuse; the Blitz’s nightly bomb raids between 1940 and 1941 did for the rest.

There are now only 13 cabmen’s shelters left standing; 12 of them are still operational. Eight of those are Grade II listed, meaning that they cannot be demolished or altered without permission from the local government, but all, Jenkins said, are cared for under English Heritage, which protects other important sites such as Stonehenge and Dover Castle. In the early 1990s, the Heritage of London Trust helped the Fund refurbish seven of the shelters.

Jenkins has been in charge of the Fund for the last eight years, and in his tenure has overseen the refurbishment and modernization of seven of the shelters. Some of the shelters have been moved completely – Russell Square’s shelter used to be Leicester Square’s shelter – and the Temple shelter, next up for refurbishment and sitting squarely where the proposed pedestrian Garden Bridge is expected to be installed, is being moved.

“The last one we just finished which was St. George’s Square had an almost total rebuild,” said Jenkins. “They have to be brought up to be modernized to conform with health regulations, food and hygiene regulations.” This has also meant some changes to the interior size; in renovated shelters, there is only enough room for about eight cabdrivers (the shelters are still only open to cabdrivers, although the non-driving public can order take-out at the window).

The cost for the St. George’s Square renovations came to around £40,000, Jenkins said. The Fund’s income comes largely from rents paid by the shelter-keepers to the Fund, although Jenkins said that the Fund subsidizes the shelters’ electricity, gas, and water bills. Since Jenkins began, rents have doubled and he says they’ll be going up again, to £150 a week, in 2017. But shelter-keepers are staying at their posts: The longest-serving shelter keeper has been at the Pont Street shelter for more than 30 years.

Rents aren’t the only source of revenue for the Fund. In recent years, the Fund saw a big boost from a deal with Universal Studios, which licensed the design for the shelter to use in its Wizarding World of Harry Potter attraction. Where the shelters sell bacon sarnies and paper cups of coffee to cab drivers in London, in Orlando, they sell cuddly stuffed Hedwigs and plastic souvenir cups of butterbeer to Harry Potter-mad tourists.

While the future for the London black cab might seem bleak, with the advent of cheap car-hire Uber, London’s mayor has recently pledged support to the embattled black cabs, setting aside £65 million to help the cabs become more energy efficient and forcing all cabs to accept credit card. But even if there weren’t any black cabs, to give up on a living link to the forces that moulded London’s city streets is unthinkable, said Jenkins: “Why would you want to give away your heritage, why would you want to give up something that has been passed down to you? Surely it’s better to preserve something like that.“

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook