How Candid Camera Spied On Muscovites At The Height Of The Cold War

Allen Funt pulls his infamous reading-over-the-shoulder gag on a Muscovite in 1961. (Photo: Candid Camera/Youtube)

In 1961, Candid Camera ruled American television.

The proto-reality show, in which everyday people were faced with ridiculous situations under the gaze of a hidden camera, was a massive hit, reaching millions across the country every week. Allen Funt, the show’s creator and punchy host, had criss-crossed thousands of miles of the United States with his film crew, then tried out his gags in Italy, France, Britain, and Germany. But he knew the same tricks don’t work forever, and he was, as always, looking for a new twist.

Meanwhile, the tensions of the Cold War ruled just about everything else outside the realm of television gags played on an unsuspecting public. The Americans and the Soviets were tussling in the air, in the papers, in outer space—everywhere but on the ground. The U.S. was backing counterrevolutionary coups in Cuba, and the U.S.S.R was testing nuclear weapons in the atmosphere. The general sense of alarm was keen enough ”that most Americans were led to believe that there were daily military parades through Red Square with Communists waving rifles,” wrote Funt in his memoir, Candidly, Allen Funt.

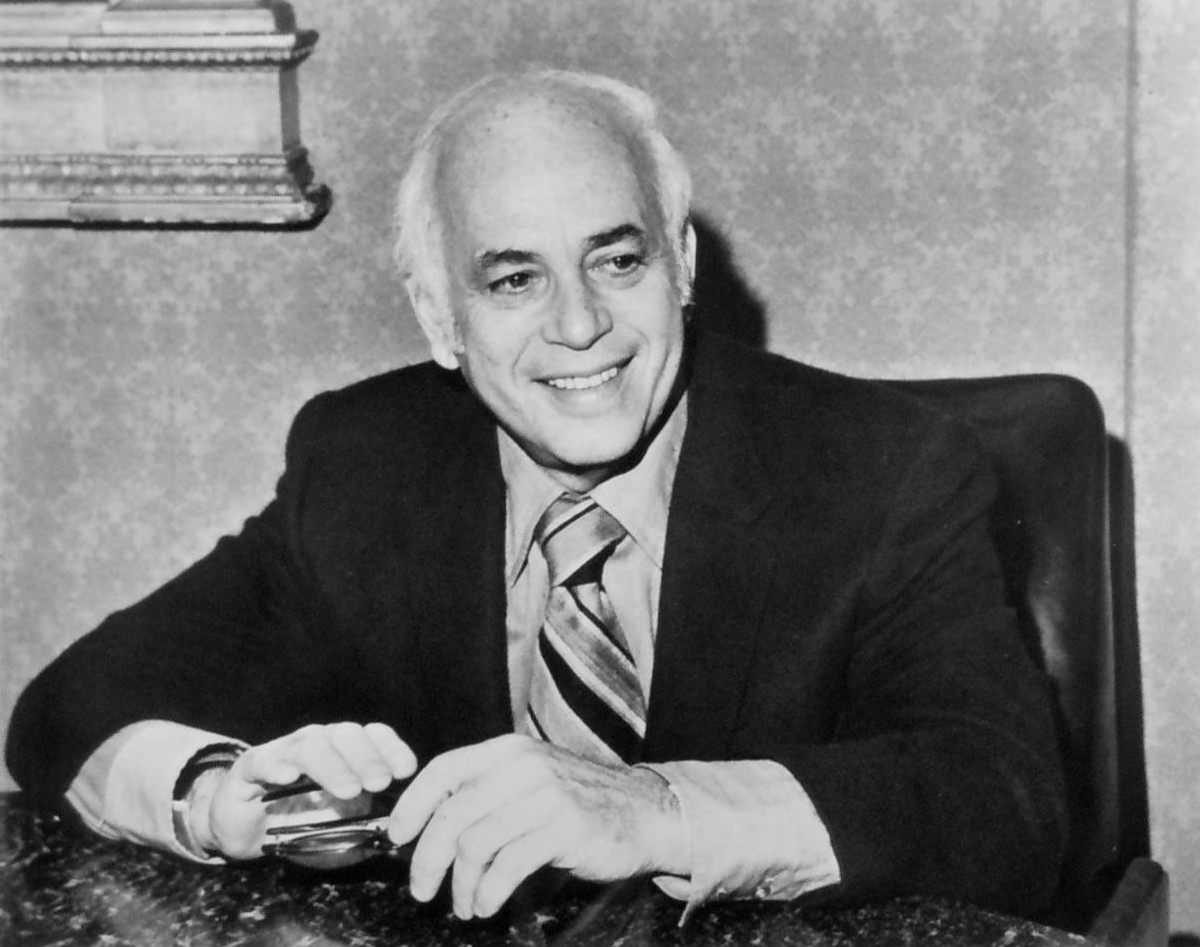

Allen Funt, host and creator of Candid Camera and unlikely infiltrator of everyday Soviet Russia. (Photo: ABC Television/WikiCommons Public Domain)

Funt, himself the son of a Russian immigrant, didn’t buy into the antagonism and distrust. Everyday Soviet citizens, he figured, were more than likely filled not with militant hatred, but with “amusing and identifiable foibles that Americans could relate to.” They, too, would surely react with chagrin to someone reading a newspaper over their shoulder, or gallantly try to help a woman carry a suitcase full of concrete. So why not film those reactions and broadcast them to Americans, to show them that Soviet had a vulnerable and hilarious human side?

Without telling his bosses at CBS, not to mention the authorities of either the United States or Russia, Funt took it upon himself to pull back the Iron Curtain and shoot a special Moscow episode of Candid Camera.

The process had its challenges. Because press passes for photographers were virtually nonexistent, he and his team used their considerable experience as everyday subterfugers to “pose as tourists.” Then, visas in hand, they packed as lightly as they could, taking small 16mm cameras that wouldn’t look out of place in the hands of so-called amateurs. Funt had nightmares about what would happen if customs opened one of the wrong bags (“how could we explain carrying 90,000 feet of film?”) but they got lucky and were waved right through.

From there, it was pretty easy for Funt and his crew to ditch their guide and start spying on people around the Kremlin, avoiding the “sensitive areas.” Calming their own nerves was a different matter. “Tension was always high when we shot Candid Camera scenes because of the unpredictability of human nature,” Funt wrote. “But now we were playing for much higher stakes. For all we knew, the KGB might throw us in a Siberian prison camp, and we’d never be heard from again.” But the team persevered, shooting film from their hotel balcony and from cars and hauling out their practiced bag of tricks (not to mention the concrete suitcase).

They soon found that their regular observations—of tourists, policemen, pedestrians, and families—were more revealing and interesting than the gags. As the above video shows, the footage they shot of people just going about their lives is intimate and, despite the narrator’s talk of “different customs,” familiar. Teenagers slow-dance awkwardly, and spectators eat ice cream at a track meet. A man spends too much on a fur hat. A pinhole camera, hidden in a cardboard box and positioned in front of a popular monument, shows how Russians pose for their own non-candid shots, arranging their families, fixing their clothes, shooing away photobombers—and, in a true twist for Candid Camera, purposefully not smiling.

In the end, the hardest part was going back home. First, Funt had to smuggle the film back through customs–something he thought he had done successfully, right up until he screened it back in New York. “Apparently, the Russian officials, knowing full well of our activities, had attempted to destroy all the film, perhaps as it was passed through the baggage service,” he wrote. They had largely succeeded, and what was left was “fogged”–not broadcast quality. Funt hadn’t been as sneaky as he thought.

The whole enterprise—secret trip, politically-fraught subject, spotty film—made for some rough conversations with the network. Newspaper articles leading up to the special Moscow episode of the show spoke soberly of CBS giving “special study and consideration” to the film, and “taking more than the usual precautions.”

The suitcase gag, Moscow-style. (Image: Candid Camera/Youtube)

When the show finally aired, in October of 1961, most of Funt’s intuitions turned out to be correct. Critics and fans alike appreciated a glimpse into Soviet life that was very different from what they were usually offered—an interview in the Milwaukee Journal teasing the episode, in which Funt says “the average Russian is pretty much like everyone else,” is bookended by other articles about films “heavily larded with Soviet propaganda,” and a new effort by the Veterans of Foreign Wars to “alert the American public to the dangers of world communism” (not to mention a suggestive baseball headline, “Yankees Beat Reds 3-2”).

Indeed, when Funt told the Milwaukee Journal, pre-broadcast, that he “ran into trouble in Moscow,” he was referring not to any security-related or political difficulties, but to the infamous suitcase gag. Some Russian men, when asked to help an American schoolteacher with her unexpectedly heavy burden, didn’t struggle gallantly or try to talk their way out of it. They “picked it up and breezed off with it,” Funt said. Sometimes, where there’s a will, there’s a way.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook