The Long-Term Effects of COVID-19 on Field Science

As scientists wait, worry, and hunker down, they’re also looking ahead to how their projects will need to adapt.

This piece was originally published in Undark and appears here as part of our Climate Desk collaboration.

If this winter had gone as planned, Bethany Jenkins would be getting ready to board a 274-foot research vessel called Atlantis right about now to head east across the Atlantic Ocean. But everything changed when the novel coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 began to infect people worldwide and touched down on U.S. shores. In mid-March, the University of Rhode Island microbiologist received word that her team’s trip had been suspended. The future of their research project—a three-ship, multi-institution investigation of ocean ecosystems that has been over a decade in the works—is now uncertain.

But as Jenkins and her team begin to pick up the pieces, she doesn’t like considering what might have happened if the trip had gone ahead.

“The people on these ships leave their families behind,” she says. “If I’m at sea, I won’t be able to help anyone on land.” The opposite is true as well: “On these research cruises, there are four people sharing each bathroom, mates sharing a wheelhouse, professional crew in the engine room and sharing berths. If something went wrong, it would be really bad.”

As the coronavirus has spread, reaching every continent except Antarctica and infecting almost a million people, scientific institutions all around the world have shut down or suspended field research like Jenkins’s, leaving many of these scientists’ work in limbo. Governments and health officials have told people to try to work from home using remote communication tools. But for the most part, field scientists can’t do that; their projects rely on gathering new information out in the world. Unfortunately, many attributes of field research—international travel, limited access to medical testing or care, long periods spent sharing close quarters—are also the very things that can help the coronavirus spread.

This halt has left scientists feeling stranded, uncertain of the future, and with more than a few logistical headaches. As grants approach their completion dates and researchers miss out on once-a-year or even once-in-a-lifetime observations, they’re beginning to grapple with how this temporary crisis will have permanent reverberations in the scientific community. The path forward for students and junior researchers, who rely on fieldwork to learn essential skills and collect data to begin research of their own, is now filled with obstacles, creating a knock-on effect for future scientific expertise. What’s more, the pause may mean delays for important advancements in many areas, from fighting climate change to preventing the next pandemic.

“Right now, we’re in a time of acute societal need that requires good science,” says Jenkins. “So there’s a real mandate to keep going forward with good science, while being empathetic with the health of the people that are really struggling during this.”

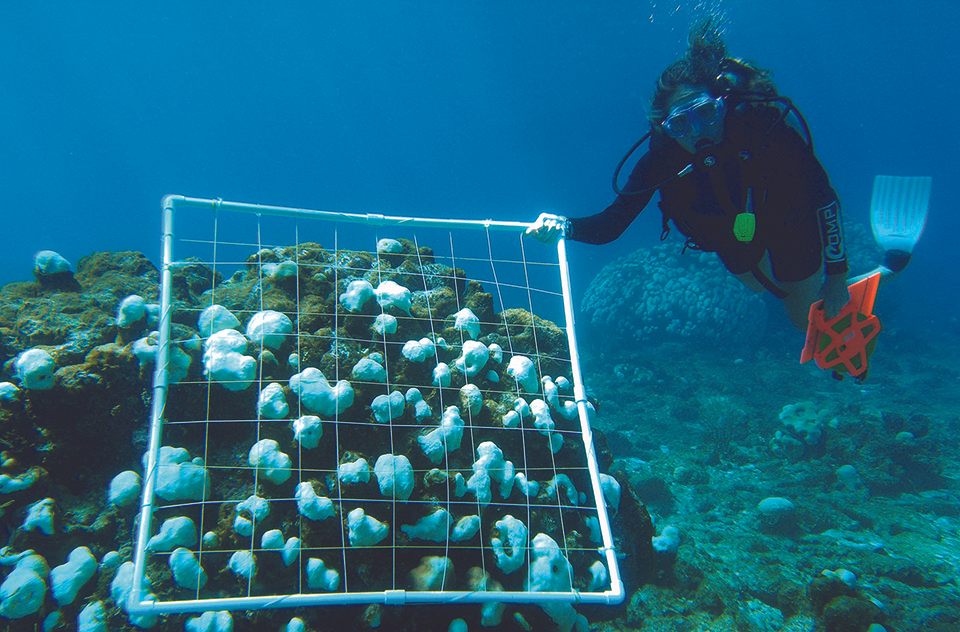

“You can’t Skype meetings with corals,” says Emily Darling, a scientist with the Wildlife Conservation Society, who coordinates monitoring for increasingly threatened coral reefs all over the globe. “Being underwater, and being with the communities that rely on reefs, is the only way we have information about the health of a reef. That information is not available remotely.”

Right now, though, human health is Darling’s priority. Her team has canceled travel to their study sites, asking all researchers to stay at home for the time being. She was particularly worried about team members visiting remote villages in countries like Kenya and Fiji, where communities might be isolated from the coronavirus until an outsider carries it unwittingly into their midst.

“While our national staff might have access to health care in urban centers, they’d be traveling into communities that don’t have that same level of care,” she says.

As her researchers shelter in place, life in the sea churns on, and Darling knows they’ll miss out on important observations. One concern is that they may not be able to adequately monitor an outbreak of a different kind this spring: an often-fatal reaction to high ocean temperatures called coral bleaching, which is currently moving across the warming South Pacific. Some information can be gathered by flying above reefs in small aircraft, but few institutions currently have access to such flights, nor do they want to expose their researchers to the cramped quarters of a bush plane.

The nature of field work makes it difficult to reschedule around delays. Field research often can’t simply be pushed off by a few months; by then, the natural events scientists want to observe may have already ended. And research vessels and field stations might be shared by hundreds of institutions, requiring scientists to get in line years in advance.

Take the case of Jenkins’ research trip, part of a broad NASA-led effort called Exports, or Export Processes in the Ocean from Remote Sensing, that’s seeking to investigate how the oceans take up and store carbon from the atmosphere (including climate-warming carbon dioxide), potentially for thousands of years. Their cruise would have monitored tiny, floating ocean plants—phytoplankton—that have their biggest bloom in the North Atlantic for only a few weeks in the spring. Because any projects currently planned for after the quarantine will still go ahead, it will likely be at least two years before her team can book a new trip.

Over the coming months and years, delaying field work also means delaying the publications that would have come out of it. Down the line, that could affect policy decisions that would ideally be based on the best and most current scientific data. This is especially concerning for scientists and policymakers tackling issues that are already on borrowed time—like in the case of Exports, which is collecting data that will allow more accurate predictions of global climate change.

With hundreds to thousands of other projects also put on pause, Jenkins sees how echoes of this shutdown will spread through the field of climate science: “If field programs that measure climate-relevant variables are being canceled or put on hold, this is a step backwards for our contributions to understanding a rapidly changing ocean.”

Ravinder Sehgal, an associate professor in the biology department at San Francisco State University, worries that delays in his field due to the coronavirus could hinder the collection of data that might help prevent the next pandemic. Sehgal studies how deforestation allows disease to spread from animals to humans, and his field work, which includes following the spread of malaria by mosquitoes and birds in Cameroon, is currently suspended. Projects like his all over the world rely on detailed timelines of how diseases progress that will now likely feature gaps of months to years.

“Without the continuity of yearly monitoring of populations, we don’t have the data we need for long-term study,” he says.

Like most science, field research often relies on grant funding that is given only for a specific time period. Because of this, chief among many scientists’ concerns is how project delays will impact early-career scientists, including PhD students and postdoctoral researchers.

When principal investigators apply for a project grant, they often will request funding to support a PhD student or a postdoctoral researcher. These funds may now expire before students can gather the data needed to finish their degrees or leave postdocs without a salary while they are still working on a project.

Matthew Smart could finish his degree without completing his field research, “though it would be a tremendous disappointment,” he says. A PhD candidate in geochemistry at Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis, Smart planned to complete his dissertation using data from a trip to eastern Greenland scheduled for this summer. His research uses samples from a particularly well-preserved outcrop of rocks there to learn about what happened when Earth’s ancient plants developed roots and began to make soil. But that trip is only possible during a short window from August to September when the study site is not blocked by ice.

Smart is still holding out hope, but he says it’s becoming increasingly likely the work will be canceled. That will push him and his adviser past the time limits on the grants funding their work, meaning Smart likely won’t be a student anymore by the time he returns to Greenland.

“There’s a significant health element to this crisis that trumps science, frankly,” Smart says. “We have to make sacrifices in order to ‘flatten the curve,’” he adds—in other words, keep the rate of infection low enough to avoid overburdening health systems.

Some grant-funded projects may be able to extend their funding to make up for lost time. For example, all National Science Foundation grants are automatically eligible for a one-year, no-cost extension, as well as additional extensions contingent on the foundation’s approval. Many universities and private foundations are developing special exceptions for research delayed by the COVID-19 pandemic.

However, these extensions don’t necessarily guarantee any additional money—just extra time. This could leave research teams in a tight spot, especially if a grant must cover salaries during the delay in addition to travel expenses.

“If this continues for long enough, my main concern is that students will either drop out of their research altogether or move to other fields,” says Sehgal. “They can’t afford to not be doing anything.”

Like the hundreds of millions of others around the world currently held in stasis outside of normal life, scientists are thinking about the future of their work in the space between communal sacrifice and self-interest. Interruptions to normal habits are necessary, and they’re saving lives. But it’s also understandable to process the conditions of this social contract through a personal lens: as disappointing, frustrating, and worrying.

The Wildlife Conservation Society’s Darling, though, sees the pandemic in another light: as an opportunity for scientists to rethink some of the ways they carry out field research. Her organization already relies chiefly on researchers based in-country, rather than flying in scientists from elsewhere in the world. That’s a model she sees as potentially helpful for other projects.

One big benefit of doing this is that it reduces their research’s carbon footprint, but that’s not the only advantage. “We know so much about the inequity of scientific resources and training, where Western researchers can travel and fly and do ‘helicopter science,’” Darling says, using a term for when a researcher spends only a brief stint in a place to gather data before heading home.

“That’s not a model that’s sustainable, and it’s not a model that’s ethical,” she says. “So this new reality gives us a chance to develop online tools for collaborations, for conferences, for workshops, and identify where we really need to travel and be face-to-face with our work.”

For now, most researchers are still trying to get a grip on the situation before beginning to plan for the future. They’ll teach classes remotely, revise their writing, and read long-put-off papers. They’ll look for ways they can help. Many are donating gloves, masks, and chemicals that they now won’t need for their work. Some are volunteering their expertise on the ground. Given their training in microbiology, Jenkins and some of her colleagues have signed up to assist with COVID-19 testing.

And they’ll wait—perhaps missing the dramatic sweep of Arctic landscapes or the stark beauty of the middle of the ocean, but staying focused on the present.

“We’re really hoping that this passes, as I’m sure the rest of the world is, so we can get back out there,” Darling says. “But this is a fast-moving crisis, and we need to take care of people first.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook