How Flower-Obsessed Victorians Encoded Messages in Bouquets

Victorians used flowers a lot like we use emoji.

A Victorian-era print of a bouquet of roses. (Photo: Boston Public Library/CC BY 2.0)

Imagine for a moment that a messenger shows up at the door of your elegantly-appointed Victorian home and hands you a small, ribbon-wrapped bouquet, obviously hand-assembled from somebody’s garden. As an inhabitant of the 21st century, your natural inclination is to be charmed by the gift, and to search for an appropriate vase. As a wealthy inhabitant of the 19th century, your instinct is a little different: you rush for your flower dictionary to decode the secret meaning behind the arrangement.

If it’s a mix of lupins, hollyhocks, white heather, and ragged robin, somebody’s impressed with your imaginative wit and wishes you good luck in all your ambitions. By contrast, a collection of delphiniums, hydrangeas, oleander, basil, and birdsfoot trefoil means you’re heartless (hydrangea) and haughty (delphinium), and I hate you (basil). Beware (oleander) my revenge (birdsfoot trefoil)—the ultimate passive aggressive present.

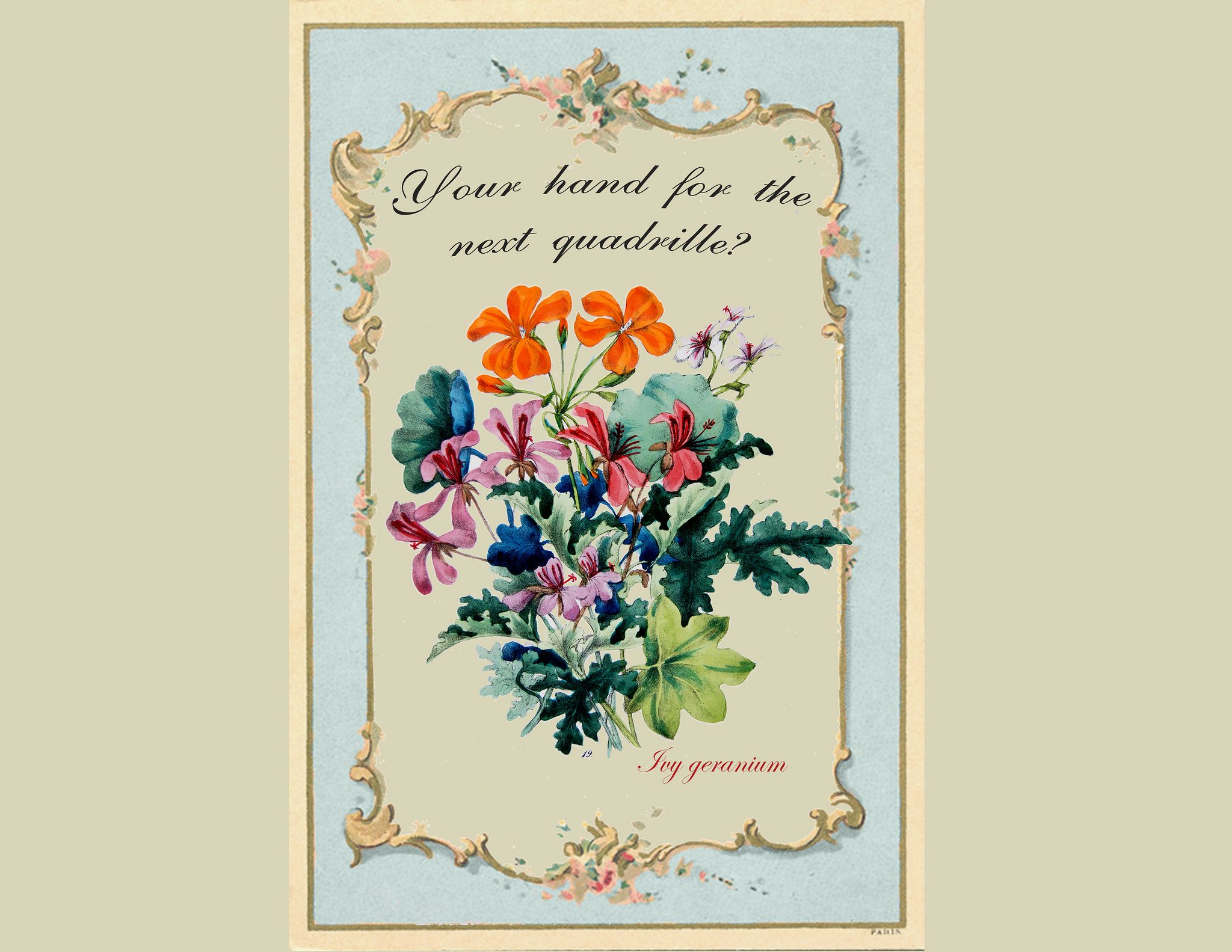

Maybe somebody sent you a mix of geraniums to ask whether they can expect to see you at the next dance. If you have any striped carnations blooming in your conservatory, you can send them to the enquirer to say, “afraid not.” Victorian flower language, or floriography, was the pre-digital version of emoji; not much separates a bouquet of flowers implying you are skipping a party from a party ghost.

Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, c. 1739. (Photo: Public Domain)

Like any symbol-based code, part of the appeal was deniability: in some flower dictionaries, the white cardamines I wore to my father’s wedding mean “paternal error”, while other dictionaries say they mean “ardor.” (I just thought they were fresh and lovely.) In the 1890s, Oscar Wilde famously asked his friends and supporters to wear green carnations which he simultaneously hinted would represent homosexuality and claimed had no meaning at all.

The long-lasting floriography fad was set off by Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, a feminist poet married to the English ambassador to Turkey. Letters she wrote home from Constantinople in 1717 and 1718 not only argued in favor of smallpox inoculation, but included an enthusiastic description of the Turkish selam (“hello”)—a secret flower language used by clever harem women to communicate under the noses of their guards.

According to Joseph von Hammer-Purgstall, an Austrian translator who penned early studies of the Ottoman empire, Montagu either misunderstood or romanticized a popular rhyming game of the time—but when Montagu’s collected Turkish embassy letters were published in 1763, the idea of a flower code quickly caught on with a fashionably Orientalist circle of educated readers. The exotic East, full of strange customs and decadence, was a powerful subject for upper-class fantasy—all the more so if it might be a source of forbidden knowledge, or a proxy for discussion of women’s repression back home. Whether Montagu had mischaracterized selam was beside the point. Harems were sexy; flowers were sexy; secret messages between lovers were extra sexy. The public wanted in.

From the 1855 book Flora’s Dictionary. (Photo: Mann Library/CC BY 2.0)

By 1810, French publishers had begun to put out flower dictionaries. People in France at the time already liked to give each other flower almanacs, presents that were halfway between a desk calendar and a coffee table book—collections of watercolor and pencil sketches of seasonal flowers, accompanied by thematically-related poems or facts. The first published flower dictionaries were appendixes to those almanacs, though they quickly spun off to form a new subgenre.

In 1819, a tome called Le langage des fleurs almost immediately became the definitive word on the subject; the translations and many plagiarized derivatives of the book by Frenchwoman Louise Cortambert, writing as Madame Charlotte de La Tour, were bestsellers on both sides of the Atlantic. These dictionaries weren’t inventing a language so much as amassing and collating the established meanings already in use, Beverly Seaton notes in The Language of Flowers: A History.

Ever since Montagu’s Turkish letters, flower language initiates had passed meanings back and forth as a gossipy secret handshake. Some of them, like a narcissus for egotism, had obvious mythological roots. Others were derived from characteristics of the flowers themselves, or from hedge-witch lore about their medical and magical properties: cabbage looked like a wad of cash, and so it meant profit; walnuts looked like brains, and so they meant intellect; pennyroyal, rue, and tansy teas were abortifacients women secretly (and often desperately) used to induce miscarriages, and so the flowers meant “you must leave,” “disdain,” and “I declare war against you,” respectively. Other plant meanings are harder to fathom—why should a pineapple, long a symbol of hospitality and wealth, instead mean “you are perfect”?—but that was part of their allure; a secret language is hardly secret if it’s obvious.

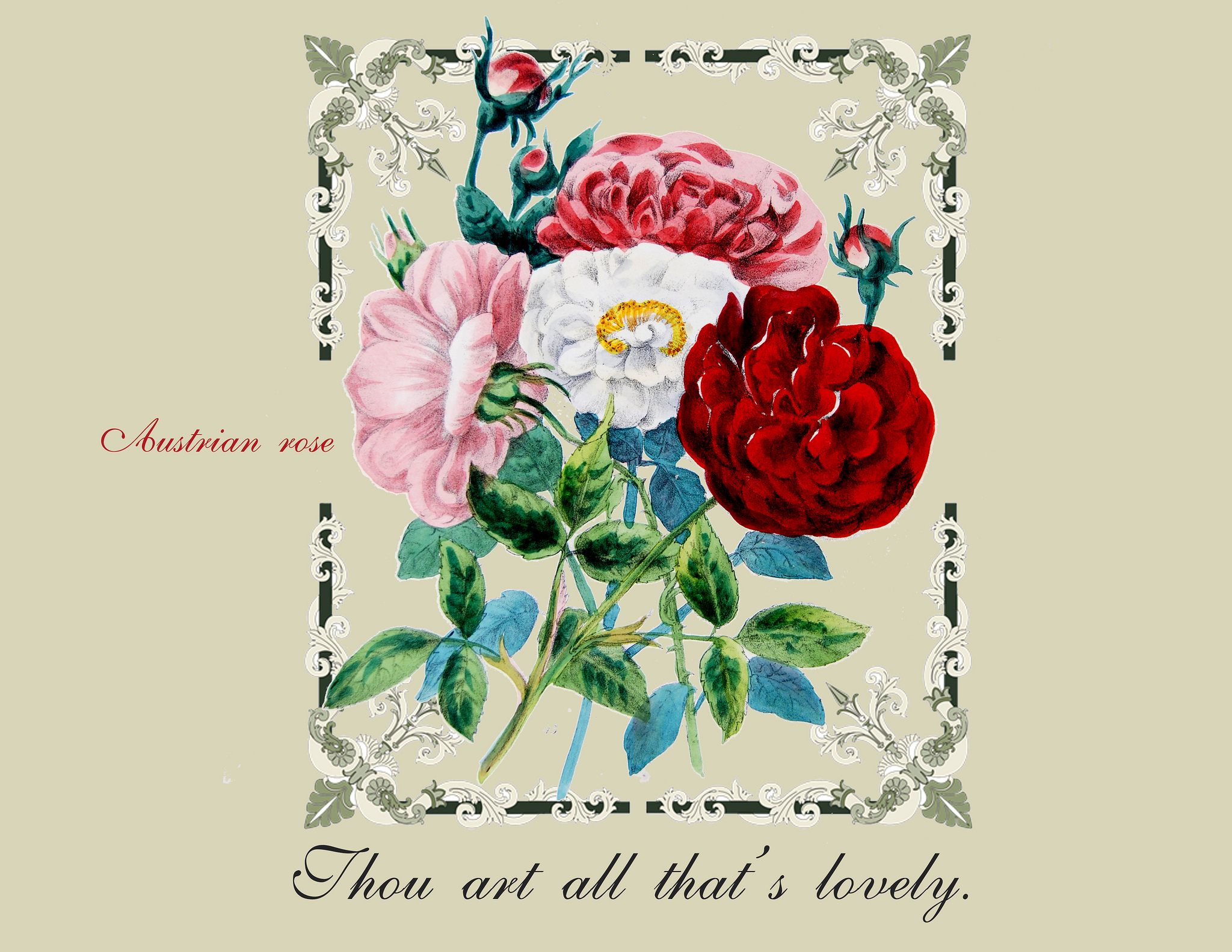

The Ausrian rose, which meant ‘thou art all that’s lovely’. (Photo: Mann Library/CC BY 2.0)

Between 1827 and 1923, there were at least 98 different flower dictionaries in circulation in the United States, and flower code was regularly discussed in magazines like Harper’s and The Atlantic. It spread way beyond actual flower bouquets, and into literature and fine art. Jane Austen and Emily Dickinson—both gardeners as well as authors—used the language of flowers in not only their writing, but their personal letters. Maybe you thought it was annoying that bits of Jane Eyre expected you to know French; Charlotte Bronte also expected you to understand that when Jane looks at snowdrops, crocuses, purple auriculas, and golden-eyed pansies in chapter nine, she’s feeling hopeful, cheerful, modest, and preoccupied with the connection between money and happiness.

Similarly, the Pre-Raphaelites relished the ability to add floral symbolism to paintings that already drew on mythic themes; Rossetti’s “Lady Lilith” might look sensual, but the white roses behind her belie a disinterest in carnality, while the poppies and foxgloves beside her suggest she’s sleepy, forgetful, and insincere. Even home embroiderers got in on the game; a woman might apply her needle to a difficult lilac pattern as a meditation on humility, or work through a marigold and pansy theme as a way to come to grips with thoughts of grief.

However, actually creating or deciphering a physical bouquet required an unusual set of circumstances—ones mostly restricted to the extreme upper class.

An invitation to dance encoded in a bunch of ivy geraniums. (Photo: Mann Library/CC BY 2.0)

In order to look up a flower’s meaning, you had to be able to identify the plants on sight, and this was no easy task with hundreds of obscure plants to choose from. For example, the ‘C’ section of the dictionary included much more than carnations and chrysanthemums; it also featured cuscuta, a crop parasite used in medieval medicine; cobaea vines imported from Mexico; and the rare, poisonous corn cockle. As it happened, botany was an insanely popular science in England at the time, especially among women.

To assemble a floral message yourself, you needed easy access to hundreds of flowers. England is often called “a nation of gardeners,” but it’s hard to believe anyone would go to the trouble of cultivating the incredibly toxic manchineel tree to someday convey the sentiment “falsehood.” Moonwort, a type of fern which means “forgetfulness,” can go dormant for years at a time, making for a very belated “sorry I missed your birthday.” Kennedia (mental beauty) is endemic to Australia, houstonia (content) is North American, and the bearded crespis (protection) is a Mediterranean wildflower easily mistaken for a dandelion (rustic oracle)—which means an off-the-cuff and easily-misinterpreted compliment could require several steamship journeys and a remarkably flexible greenhouse.

The latter would have been impossible in most eras, but aristocratic Victorians benefited from an unusual confluence of concentrated wealth and new industrial processes. Technological advances in the manufacture of architectural glass meant the sufficiently wealthy could build mansion-sized conservatories (a great way to show off), and since coal and labor were both very cheap, they could heat their indoor gardens to tropical temperatures year-round, and employ live-in staff to look after temperamental non-native plants they might want to harvest for flower messages.

An illustration from Robert Tyas’ The language of flowers: or, Floral emblems of thoughts, feelings, and sentiments. This bouquet suggests “your modesty and amiability inspire me with the warmest affection”. (Photo: Internet Archive/Public Domain)

By the end of World War I, floriography had largely vanished, as nations and families shifted their attention and resources to war and its long aftermath. Grand estates tore down their hothouses, or converted them for other purposes (a few survive as museum attractions, like the restored Wentworth Castle conservatory in Sheffield, England). Once the wealthy stopped assembling physical message bouquets, their disinterest gradually trickled down; after all, it’s no fun to label-spot if nobody’s wearing couture. Urbanization took artists and writers away from nature, and the cool kids turned their attention elswhere. Georgia O’Keeffe’s flowers may have represented something beyond themselves, but their not-so-secret meaning doesn’t take a dictionary to decipher.

Today, most people prefers to send ambiguous imagery through digital devices instead of plants. Massachusetts florist Jennifer Collins says the only symbolic flower people ever request is the lily—which they want left out of their bouquets because of its link to funerals. (White lilies are a symbol of the Virgin Mary, and represent purity; they’re a popular way to convey a return to innocence in death.)

Even in lavish wedding ceremonies where every element is planned in obsessive detail, very few bouquets are assembled to send a floral message; according to the team at wedding florist I Love Roses, contemporary brides are more often concerned with replicating an attractive image from Pinterest. A notable exception is Kate Middleton, now Duchess Catherine of Cambridge and presumably England’s future queen. When she married Prince William in 2011, she deliberately gave the nod to Victorian flower language, choosing flowers less for their looks than their meanings: myrtle and ivy for love and marriage; hyacinth for sports (the couple reputedly bonded over a shared love of athletics); sweet william for gallantry (a reference to her own sweet William).

Most likely, floriography will live on as a tool for miscommunication as long as there are dramatically-inclined introverts with feelings too strong to say out loud. And knowing the code still has its uses, even for the less neurotic. When I was a kid, a family friend found out her husband wanted a divorce thanks to a bouquet of yellow roses. She thought it was a sign he hoped to reconcile, but her flower-literate sister knew the score. (Yellow roses mean “let’s be friends.”) Sure enough, a few days later, he said it with words—and she was able to give him a dignified response, thanks to the forewarning of a carefully-chosen posy.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook