How I Learned to Keep the Peace at a Hippie Festival With No Rules

When 10,000 people camp out together at the Rainbow Gathering, staying groovy can be a challenge.

Blessing to the four directions. (All Photos: Livia Gershon)

When I wandered into an internet forum for members of the Rainbow Family of Living Light and started asking about going to their long-running national gathering, the responses were friendly, but a little unnerving. In the midst of a series of messages about Rainbow etiquette, one person briefly noted that “some bad things have a potential 2 happen. If ya ever have trouble just yell ‘shanti sena’, & some help will be on the way.”

Another mentioned that the gathering attracts “an interesting group with very mixed purposes.” Be cautious, she warned. “If you get into trouble yell SHANTI SENA and help will come.”

I wasn’t quite sure what to make of this. If I did find myself in a scary situation out in the forests of Vermont, I was pretty sure there was no way I’d remember the phrase “Shanti Sena.” Surely “help” would work just as well? How do you even pronounce “Shanti Sena” anyway?

The ‘Welcome Home’ sign that greets arrivals at the Rainbow Gathering.

As I trudged up the road toward Mount Tabor, the site of the Rainbows’ 2016 annual gathering, it quickly became clear that the Rainbow-specific lingo was no joke. Close to a dozen people—men and women with an assortment of giant backpacks, long beards, flowing skirts, and adorably grubby children—greeted me with the phrase that also appeared on banners hanging from the trees: “welcome home.”

Some Rainbow terms are pretty self-explanatory: The gathering is home, while the commercial world outside is Babylon. Men and women are brothers and sisters. The holes that volunteer crews dig in the ground are shitters.

Others are less so: Getting people organized to do something is “focalizing.” Any sort of activity, from a meal to a fistfight—particularly ones that are fraught and absurd—is a “movie.” Shanti Sena, named after Gandhi’s nonviolent Peace Army, is the term for any kind of peacekeeping (and it’s pronounced pretty much the way it looks).

Cooking at the Shining Light Kitchen.

The Rainbow Gathering began in 1972, when more than 20,000 people gathered in Colorado, chanted for world peace, and camped out together. Since then, they’ve done the same thing for a few weeks around the 4th of July every year, in one forest or another. People organize kitchens to cook meals and provide for the basic needs of whoever shows up—10,000 people this year, according to the U.S. Forest Service.

This all happens with no formal organization and without any money being exchanged. People pass a hat to buy rice and beans and kale, and bring coffee and tobacco and weed to share (though alcohol is strongly discouraged except in an especially rowdy camp on the periphery of the gathering). Dozens of smaller regional gatherings also happen throughout the year.

In theory, no one at a gathering is the boss of anything. Outside of theory, at the 2016 national gathering, Karin Zirk was the boss of Shanti Sena—the one who focalized the workshop to share tips on the subject, the one people went to when something was going wrong. Zirk is a middle-aged database administrator for a San Diego biotechnology company. She’s been coming to Rainbow Gatherings since the late 1980s.

“I took vacation days to come out here and work much harder than I do there,” she tells me.

For Zirk, peacekeeping starts with prevention—making sure everyone is hydrated, fed, and reasonably well-rested. That, of course, doesn’t always work. If something serious goes down, whoever sees it is supposed to yell Shanti Sena, and everyone who hears it is supposed to run to help—provided they’re reasonably sober and not in the mood to beat someone up. Sometimes, a group surrounds the person who’s causing problems and chants Om, which Zirk insists can help change the energy of a situation.

Not that any of this turns the gathering into a paradise of nonviolence. Last year there was a fatal shooting at a gathering. The year before that, a woman known as Hitler stabbed a guy at another one.

But Zirk says a lot of bad situations do get diffused. Just the previous day, a guy who was out of his mind on some drug had been threatening people. Shanti Sena was called, and someone came to help. A group of medical volunteers quickly arrived, duct taped his wrists and ankles, and brought him to the medical tent for treatment.

Activities in the meadow.

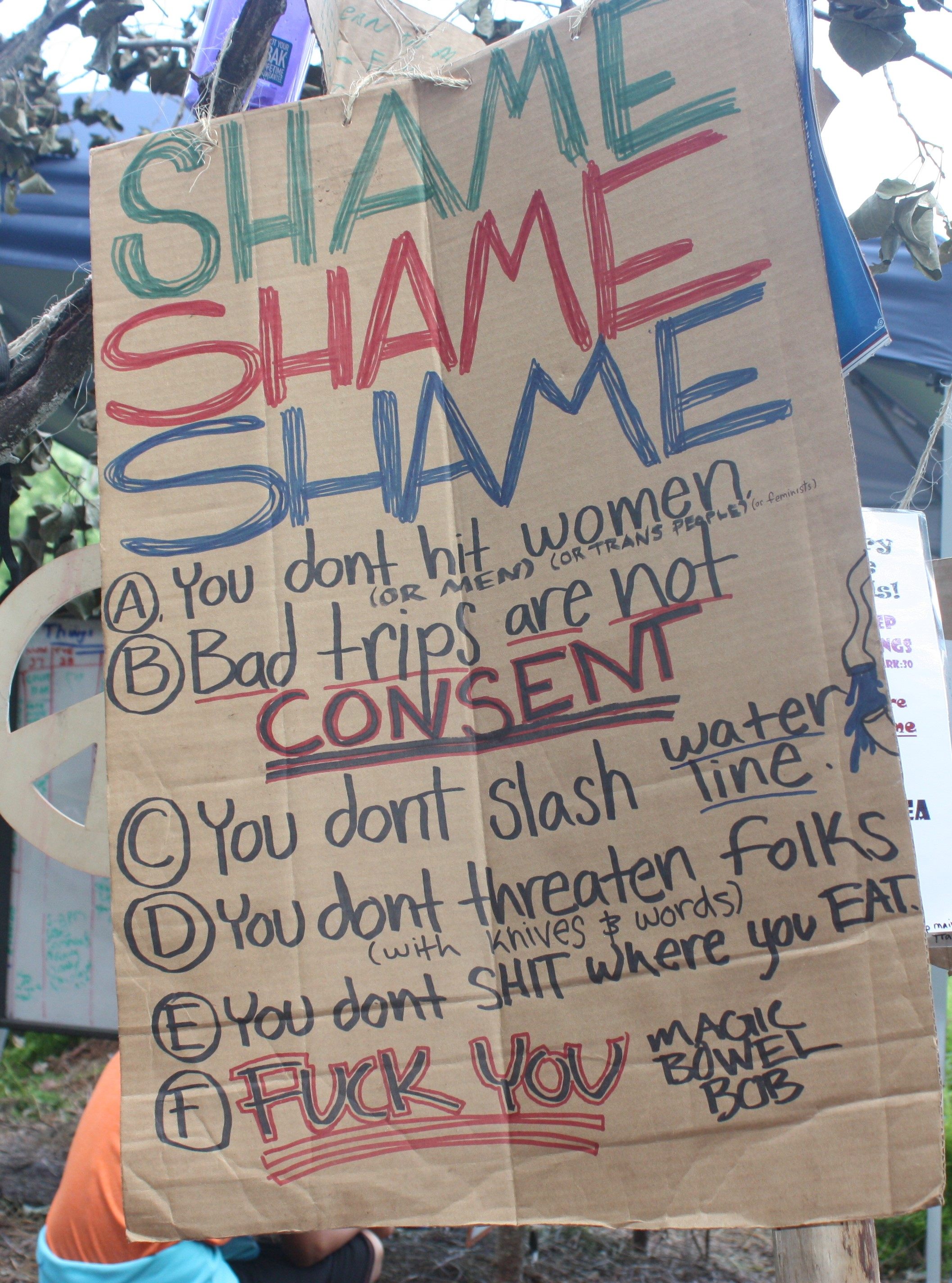

Within an hour of talking with Zirk, I hear what turns out to be the beginning of a new Shanti Sena movie. People are marching toward a kitchen on the edge of the gathering shouting and holding signs. “SHAME, SHAME, SHAME” they say. Also “Fuck You, Bob.”

This, it turns out, is the culmination of a conflict that’s been going on for years. According to the marchers, Bob, the guy who focalizes this kitchen, has caused all manner of havoc. At a previous gathering in Montana, they charged, he cut a water supply line, dug a shitter within 40 feet of the kitchen—a huge sanitation no-no—and pushed a woman who confronted him on his behavior.

This week, there was a new incident. According to the protestors, a woman approached Bob wondering if she was having a bad trip, and if he was a trustworthy person who could help. He responded with a hug that included groping her ass and a suggestion that she come into his tent for some water. Later, when two peacekeepers approached him, he brandished a knife and threatened to pour hot soup on them.

This is the tricky thing implicit in those messages I got about Shanti Sena. At a gathering, everyone’s invited, and there’s no formal protocol for a situation that pits one person’s free participation against everyone’s health and safety.

In this case, though, a sizeable group has decided that Bob must leave. They surround the kitchen, chanting. There are some self-conscious jokes about being an angry mob, but it’s mixed with genuine hostility. A young woman wearing a flowing scarf and a grim expression hands out “shame cookies” decorated with frowny faces that she’s prepared for the occasion.

A sign protesting Bob, one of the attendees.

Finally, Bob sits down in a folding chair across from one of his accusers. He’s 55, with disheveled hair and glasses. Like some of the protestors, he’s smoking weed. He’s sorry for what happened in Montana, he says. “I apologize for being a raving lunatic dickhead.” He says he had just quit drinking at the time and was a mess.

“I wish I had known that,” the victim responds quietly.

But she says the issue isn’t just that he did something wrong—it’s that he did it from a respected position. “People look up to you because you focalize the kitchen, as someone they can trust,” she says.

When the topic turns to this year’s accusations, Bob is not so apologetic.

“Yes there was a hug, and I like girls, and I may very well have touched her ass,” he says.

The conversation goes on for a while, in more or less heated terms, with some other volunteers from the kitchen defending Bob and calling for him to get another chance.

At one point, a fight breaks out between two dogs, and a member of the kitchen crew shouts “this is the vibrations we’re sending out with our energy, everyone!”

“It’s a dog with balls behaving like a dog with balls!” a protester shouts back.

Finally, though, the movie comes to an end. Someone has given Bob some money to help him on his way, and he’s agreed to leave immediately. With another kitchen volunteer pushing a wheelbarrow full of his possessions, he walks out of the gathering, followed by a line of protesters. Someone is playing an accordion. Adding to the carnival feel, among the protesters is presidential candidate and performance artist Vermin Supreme (platform:“When I’m President Everyone Gets a Free Pony”), a longtime Rainbow, carrying a walking stick-sized toothbrush.

Zirk, who’s been watching the whole incident mostly from the sidelines, says she’s satisfied that the whole thing resolved nonviolently.

“I’m just really happy that everybody held their peace, and the people who couldn’t hold their peace were self-aware enough to stay back,” she says.

Cooking at the Stock Pot Kitchen.

Shanti Sena is, of course, just one small part of the complex, messy mechanics of a gathering of this shape and size. Wandering through the meadow that forms the center of the temporary city, I meet men and women who view the gathering as a welcome place to recharge, and others who’ve found a full identity in their summer Rainbow roles.

At Stock Pot kitchen, where a bunch of twenty-something kids were grating potatoes and brewing coffee, a volunteer named Cal says he’s come back to the Rainbow Family after a brief stint trying to work a normal job.

“It was fine for a while,” he says. “I definitely enjoyed the regular showers.”

But, one day, he woke up hungover and sick of the way his life was going.

“I just realized I’m in this cycle of working a shitty job and getting fucked up and not being able to afford a place to live,” he says.

When he’s traveling with the rest of the Stock Pot crew—going from gathering to gathering, with stops at farms where they trade labor for room and board—he doesn’t drink.

“I feel like I’m accomplishing something, giving myself a story to tell,” he says.

On a trail through the meadow, I meet Serendipiti, a woman who started hitchhiking around the world at 19 and hasn’t stopped for close to seven years. Last year, she says, she traveled to 13 countries, spending a total of $7,000.

When I asked if she ever feels unsafe, as a woman traveling alone, she answers “I’m kind of a bad-ass” without a glimmer of irony. But Rainbow Gatherings don’t always seem like the safest place to her, but she was at the protest against Bob earlier in the day, and it made her feel more confident in the community.

“That’s the type of shit I like to see at Rainbow,” she says. “I get involved in that, and it makes me feel safer.”

The dish-washing station.

Later, in the meadow, a woman offers a blessing to the four directions, and thousands of people hold hands and chant Om. Bare-breasted women wear headbands crafted from maple leaves. A man in a literal tinfoil hat tells me photographs really do steal your soul—he knows because when he buried a data stick in his yard, mushrooms grew in that exact spot.

When the sun gets low, hundreds of people cluster close together to dance and clap and drum. A small group of men and women strip naked and improvise a gymnastic dance. A bonfire shoots sparks above the tops of tall trees that border the meadow.

No doubt, some of the brothers and sisters in the meadow were what the Stock Pot crew tells me are called festy kids—people who come to the gathering looking for a party and wondering where they can get some molly. But others have spent weeks putting up tarps and pushing wheelbarrows of cabbage up steep forest roads and setting up water filters and practicing Shanti Sena to keep their gathering safe.

As I head up to my tent, I see Karin Zirk, still working the information table. I ask her why she does it—why she works harder here than she does at her real job, mediating conflicts and sitting with angry people.

The point, she says, is not to facilitate a party where people can enjoy weed and psychedelics in a basically friendly setting deep in the woods. She says it’s something more like a yoga or Zen practice.

“This is how the world could be all the time, and we’re practicing here,” she says, “Trying to figure out how we can do things that resonate with our hearts and live in peace with each other.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook