How Kurobe, Japan, Became the Zipper Capital of the World

Reverse engineering and the Cycle of Goodness™ helped make YKK a universal brand.

There is not a groin in the world that the city of Kurobe has not touched.

It has done so through the auspices of YKK, the world’s largest manufacturer of zippers, which produces roughly half the world’s supply—some 7 billion a year. Yet to understand how Kurobe became the zipper capital of the world, one must travel back to the very birth of the zipper, to a time when the zipper wasn’t even the zipper at all.

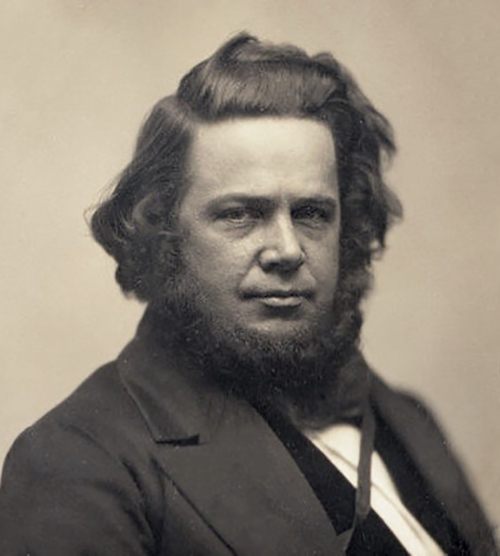

It was in the midst of the Victorian Age that mankind suddenly grew disquieted with the button. Along with brooches, buckles, and pins, the button had ruled supreme as a clothes-fastening device since ancient times. Yet it would soon face its stiffest competition to date. Elias Howe, the magnificently coiffed inventor of the sewing machine, sounded the first warning shot against the button’s dominance when he patented an “automatic continuous clothing closure” in 1851. His invention was forgotten amid all the hemming and darning, but ripples were already spreading out into the placid pond of fastener innovation.

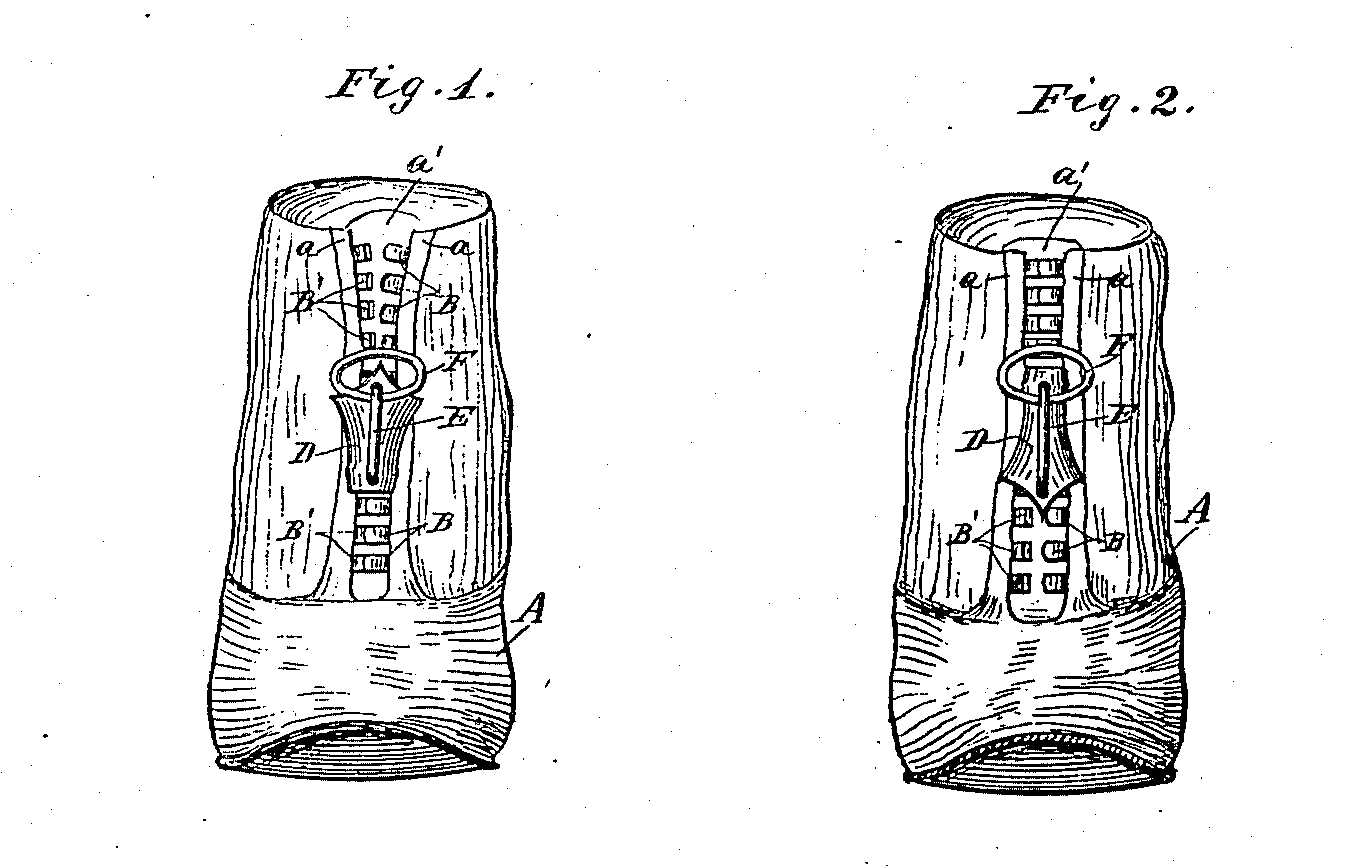

They reached the obsessive Chicago inventor Whitcomb Judson toward the end of the 19th century. Judson abruptly felt the need to free people from the tyranny of high-button shoes. He intended to do so through the creation of what he termed “clasp lockers.” But his invention was too bulky, and his fanatical redesigns grew ever more complex and impractical. Abetted by his financial backer, Colonel Lewis Walker, Judson founded the Universal Fastener Company, even though the device had a fatal flaw—a propensity to burst open at inopportune moments. The pair’s most high-profile sale was to the U.S. Postal Service, which tried them on its mail sacks. But they bought only 20.

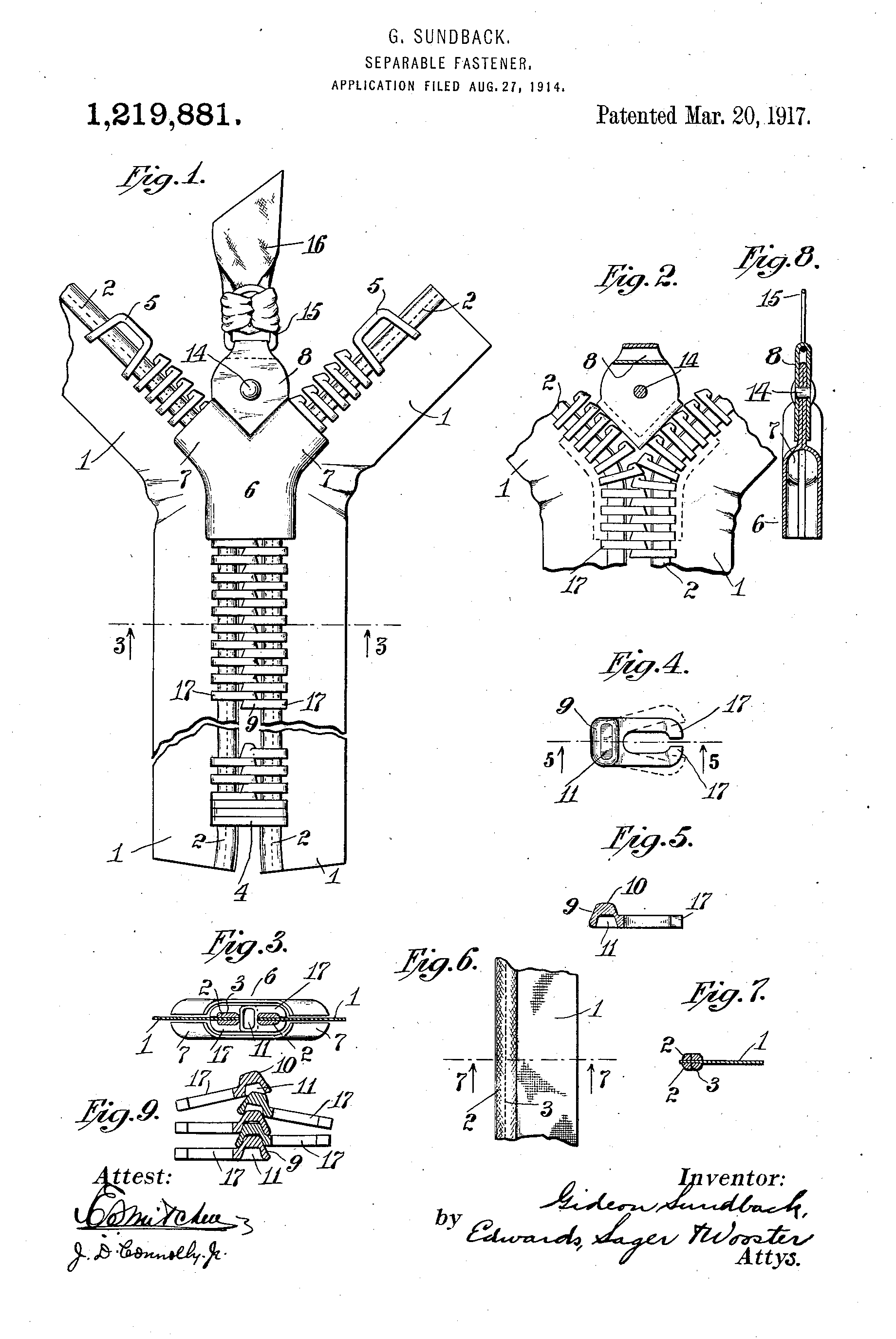

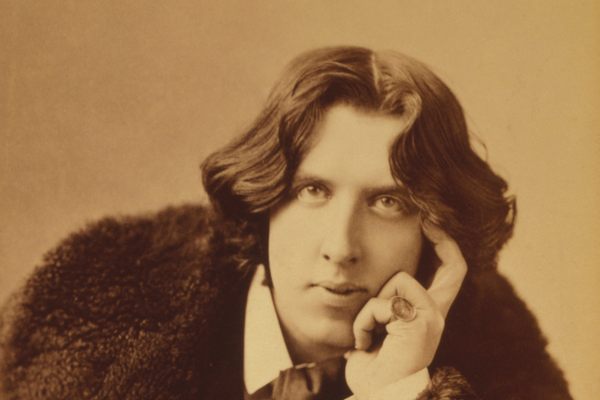

Perhaps Judson’s alarmingly wide array of interests—he designed both street railways and nose rings for hogs—prevented him from perfecting the device. It was left to Gideon Sundback, a Swedish inventor working for the Universal Fastener Company, to finalize the design with his own “separable fastener” in 1914, and at long last it seemed as if the world was ready to embrace the device. It was, after all, the era of the motor car, the tank, and the airplane. The natural was rapidly being supplanted by the man-made. So, too, in the world of fasteners. Out went the old organic forms—discoidal (circular) buttons and hook-and-eye fastenings—and in came a clothes conjoiner for a new mechanical age, in which two rows of protruding metal teeth clamped together like some fearsome haberdasher dentata.

The separable fastener was something out of a Futurist’s utopia. All it needed was a suitably modern name. That eventually came thanks to the B.F. Goodrich rubber company, which installed Sundback’s fastener on its boots in 1923. As recounted in Robert Friedel’s essential zipper tome, the boot was originally called the “Mystik,” but it sold terribly. The inspiration for the new name came from the company president: “What we need is an action word … something that will dramatize the way the thing zips … Why not call it a Zipper?”

It was a moment akin to Lennon meeting McCartney, Jobs meeting Wozniack, Kanye meeting Kim. The device’s onomatopoeic name sang of the modern, of speed and frivolity. Ziiiiip! The world of pants would never be the same.

The Universal Fastener Company, renamed Talon, set up shop in Meadville, Pennsylvania, and began mass-producing its zippers. By 1930, 20 million Talon-made zippers were being sold a year, but mainly for unglamorous functions such as pencil cases, bun-huts, and engine covers. However, when the fashion designer Elsa Schiaperelli used them in her 1935 spring collection (which the New Yorker described as “dripping with zippers”), the humble closure entered the world of high fashion. Menswear followed. In 1937 Esquire announced that the zipper had beaten the button in the “Battle of the Fly.” By the end of World War II, Meadville was selling some 500 million zippers a year and was renowned as the zipper capital of the world. Its radio station was named WZPR.

So how did a small rural town in Japan, half a world away, come to dethrone this zippering behemoth? It was through the single-minded visionary purpose of Tadao Yoshida, the founder of Yoshida Kōgyō Kabushikigaisha (Yoshida Manufacturing Shareholding Company) from which YKK is necessarily abbreviated.

Yoshida had grown up in Kurobe, the son of an itinerant bird collector. After a slew of business failures, he moved to Tokyo and, seeing the growth of the zipper market, opened his own zipper firm in 1934. The success of Talon was known around the world and Yoshida shamelessly copied its products and machines while adding some distinctive touches—such as using aluminum instead of copper. When World War II began, he kept in business by supplying the Japanese Imperial Navy with zippers, and when his factory was burned to the ground during the firebombing of Tokyo in 1945, he relocated to his hometown of Kurobe and began all over again.

Yoshida’s remarkable stick-to-itiveness had been spurred by reading Andrew Carnegie’s The Gospel of Wealth. Now, as if infused with the reciprocal force of the zipper, he too created a quasi-philosophy that he termed the Cycle of Goodness™. This stated that “no one prospers without rendering benefit to others.” It is a simple but enlightened creed that suggests that well-treated workers create a better product, a better product benefits customers, and satisfied customers, in turn, benefit YKK. In short, Yoshida wanted to use his zippers to bind together not only clothes but also the very fabric of society.

YKK was unusual in that it produced everything used to make its zippers in-house. Brass, aluminum, polyester, yarn, were smelted and woven in Kurobe. Workers lived in dormitories opposite the factory and a leadership cult quickly grew up around Yoshida and his Cycle of Goodness™. Gripped by zippering inspiration, YKK’s designers began churning out thousands of different types of zippers aimed at specific industries and individual customers. It made the world’s smallest zipper, the concealed zipper, the first nylon and polyester zippers and the world’s thinnest zipper. A pantheon of patented fastenings rolled off the factory line—Beulon! Eflon! Zaglan! Ziplon! Minifa! Kensin! Natulon! Excella!—each seeking to create a more perfect union. Soon YKK was opening factories across the world, the better to offer their services to local manufacturers. By 1974, YKK was making one quarter of the world’s zippers, enough in one year to stretch from the Earth to the Moon and back again.

By contrast Talon, which in the late 1960s was producing 70 percent of the United States’ zippers, was barely producing half of that. Its decline was rapid. By 1993 Meadville no longer had any zipper factories within its town limits at all.

Meanwhile, Kurobe and YKK goes from strength to strength. It now makes silent zippers for soldiers on the battlefield, fire-retardant zippers for firemen, airtight zippers for astronauts. It makes zips for drainage ditches, zips for rockets, and zips for fishing nets. Occasionally there are snags, such as when an exporter in the deep South of the United States began importing zips with KKK on them to appeal to local markets, or when YKK was accused of operating a zippering cartel. Similarly, market share is constantly being eroded by thousands of tiny Chinese zipper concerns that have managed to reverse-engineer YKK’s closely guarded zipper-making machines, as YKK once did itself.

Nevertheless, YKK remains a universal brand. Its zippers sit like tiny symbiotic aphids on our clothes, offering immediate access or exclusion to our bodies. From its headquarters in Kurobe, YKK has become the gatekeeper to the world.

This article was first appeared on August 31, 2015.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook