How Should Humans Divvy Up Mars?

No one can claim sovereignty of Mars, but there are ideas about how best to use the land.

A hole dug by the Curiosity rover. (Photo: NASA/JPL-Caltech/MSSS)

Land use policy is one of the most emotional and provocative areas of law. Witness the anger about a bike lane. Consider the angst around tall buildings, wind farms, and public land designations. Earthlings have developed very strong feelings about what’s theirs and what goes next to it.

Now imagine what will happen when a small group of people take those same preoccupations to Mars.

A few people who study life in the universe already are working on thinking through land use on other planets. “In the grand scheme of things, with the growing commercial exploration of space, it’s not premature to think about these questions,” says Charles Cockell, a professor of astrobiology at University of Edinburgh.

“Basically all the globe has been claimed,” says Jacob Haqq-Misra, a research scientist at Blue Marble Space Institute, whose new paper details a “Practical Approach to Sovereignty on Mars.” For him, the big question is: Does it make sense to carry the colonization mindset of the past to space, in the future?

On Earth, land use policy is a muddle of zoning and compromises. On Mars, when humans arrive, assuming we don’t find Martians, we will have a clean slate. How should we split the planet up—if we do at all?

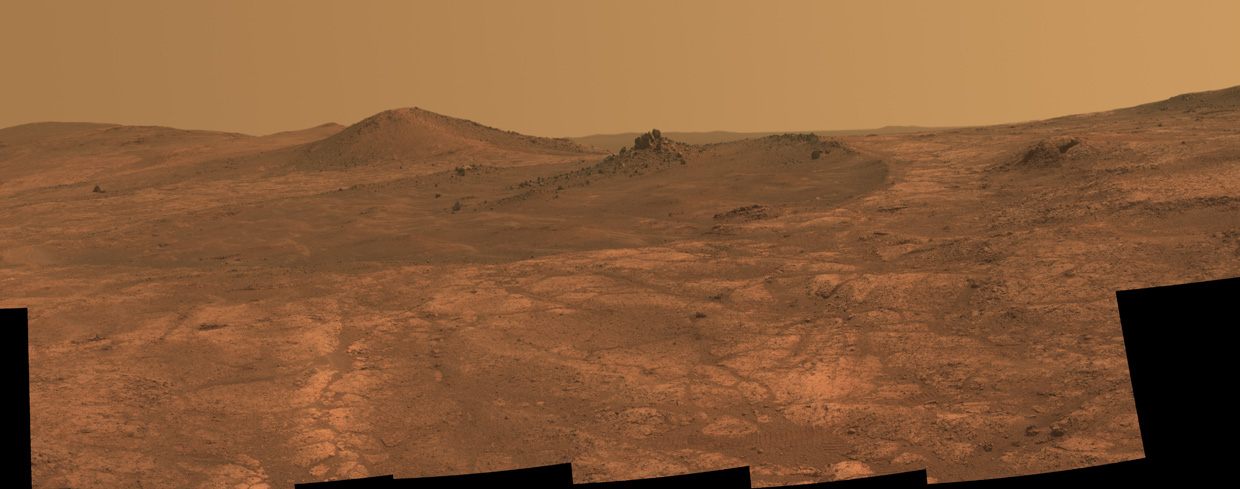

Twin peaks. (Photo: Timothy Parker/JPL)

There are previous claims to land on Mars. In 1954, a group of Arkansas men founded a Planet Mars Development Corp. to start making claims. By 1956, the Japan Astronautical Society, organized to promote the country’s interest in space travel, was giving away 80 acres stretches as part of its membership package. In the 1980s, Dennis Hope, an American entrepreneur, claimed Mars, along with the Moon, as his own; today it’s possible to buy plots at moonestates.com or buymars.com. (There’s even a GroupOn voucher available.)

Compared to claims to the Moon, though, assertions of private ownership of Mars have been few and far between, perhaps because earthlings were convinced for many decades that there could be aliens living on the Red Planet already.

No part of space is supposed to be claimed as sovereign land. You can’t rule part of Mars. For the past 49 years, humans have explored space under the auspices of an international agreement, the Outer Space Treaty, in which signatories agreed: space was “the province of all mankind” and should be used “for the benefit and in the interests of all countries.”

That was an easy enough sell when only the U.S. and the Soviet Union had actually been to space. Then-U.S. president Lyndon B. Johnson, faced with space budget cuts, was worried the USSR would claim the moon; the rest of the world was worried about being blasted by space nukes. But with commercial companies and government space agencies promising that trips to Mars will start sometime within the next two years (SpaceX), or the next two decades (NASA), that agreement is about to be challenged.

The base of Mount Sharp. (Photo: NASA/JPL-Caltech)

Already, last year, the U.S. passed a space law that could violate the Outer Space Treaty. In delightfully mundane legalese, the law covers the permitting of rocket transit: for example, “reusable launch vehicles” can get a permit for “an unlimited number of launches and reentries”—but not if they’re carrying a “human being for compensation or hire.”

It also entitles U.S. citizens to “any asteroid resource or space resource obtained” in commercial recovery operations. That’s the part that could violate the treaty, although the law claims this is different than asserting sovereignty over a celestial body, which is explicitly prohibited.

Either way, far from reserving space resources for the benefit of all mankind, the U.S. government’s current policy asserts that if you grab something valuable in space, it should be all yours.

The view from Rocknest. (Photo: NASA/JPL-Caltech/Malin Space Science Systems)

At the moment, no one really knows where the prime spots on Mars will be, either for scientific research, survival, or commercial exploitation. Space explorers are in essentially the same position as Europeans were in when they started traveling to North America: they believed there was something valuable (gold, they hoped), but they had no idea where it might be.

But let’s presume, as many space policy experts do, that space explorers will try to claim part of Mars for their country or company, or at least try to derive some commercial benefit from the place they land. What should happen when people do reach Mars?

A couple of years ago, Haqq-Misra, of the Blue Marble Space Institute, proposed “a simple solution” for determining land use on Mars: let the people who make it there hash it out for themselves, with no interference from Earth. This idea was part of a larger proposal to “liberate Mars from the start,” he wrote in the Boston Globe. “Colonists arriving on a liberated Mars would relinquish their former status as earthlings and embrace a new planetary citizenship as martians.”

In this system, the new citizens of Mars would develop their own rules and regulations for land use (and every other form of law and order). No earthlings could own land on the planet, either. This system has the advantage of fitting with earth-bound legal precedents for making land claims—you have to live in the place first—and it excuses Earth from enforcing laws made on this planet more than 140 million miles away.

Mars. (Photo: NASA/JPL)

An older idea for divvying up land on Mars, which Cockell, the Edinburgh professor, proposed back in 2004, would designate large chunks of the planet’s surface as parks. Like parks on Earth, these “planetary parks” would be sites of scientific interest, natural beauty, or historical significance. They might protect areas where life is most likely to be found, the large volcanoes there that dwarf Mt. Everest, or the sites where Mars rovers landed. They’d be accessed only along predefined routes, by sterilized robots or people in sterilized suits, and no space vehicle would be allowed to land there.

“It’s a counterpoint of a libertarian, free enterprise view” that should govern the rest of the planet, say Cockell. “The conditions are so extreme that you want to minimize regulations.” But there should also be some way to set aside at least some part of the planet where economic motivations don’t take precedence. “Even though the surface of these planetary bodies is very large and it’s not like anyone will overcrowd them, some sort of conservation ethic should be part of settling these places.”

What about the rest of the Red Planet, where people might actually live? A few years ago, David Collins, a lecturer at City University, London, proposed a “limited form of first possession” as a model for Mars land use. Essentially, if you land on Mars, you’re allowed control and use of land within a certain radius (Collins suggests 100 kilometers, or about 62 miles) from your landing spot.

Martian ground. (Photo: NASA/JPL-Caltech/MSSS)

Last month’s paper, by Haqq-Misra and co-author Sara Bruhns, proposes a “pragmatic approach” that combines these two ideas, of parks and limited possession. Their proposal stays more or less within the bounds of the Outer Space Treaty, because while it allows economic exploitation of Mars’ resources within a colony’s boundary, it does not establish sovereignty over those parcels of land. What that would mean, in practice, is that newcomers could camp out in an established colony, without permission. They would only have to negotiate use of resources with the colony’s borders.

It’s easy to imagine that this could lead to conflict. Imagine that your younger sibling came and sat in your room. Even if they’re not eating your snacks or playing with your toys, their very presence could get on your nerves after awhile. Presciently, Bruhns and Haqq-Misra also added a system for resolving conflicts on Mars. Every colony established, they suggest, will govern itself, but Mars settlers should also establish a “Mars Secretariat” to resolve conflicts with between colonies.

“If that broke down, the host nation is responsible for the ones it sends into space,” Haqq-Misra says. “But you could imagine a wide-scale rebellion, and the time it would take to organize a law enforcement mission from Earth to Mars. That’s one reason I like my idea of Mars liberation. It’s a little more radical, but it forces us to come up with new solutions to these problems.”

That sort of flexibility might be necessary, too: settlers on Mars may have to live underground in soil that’s toxic to human metabolic systems to avoid exposure to radiation. Whereas people on Earth usually divide the rights to land between surface rights and mineral rights, people on Mars may need completely different ideas for how to divvy up space, both above and below the ground.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook